One chilly day in November 1917 the air over Rhode Island’s Greenwich Bay resounded with the then unusual roar of an aircraft engine. A graceful seaplane rose from the water around Chepiwanoxet Point in Warwick near the East Greenwich town line. It was a Gallaudet D-2 airplane, the brainchild of a brilliant engineer named Edson Fessenden Gallaudet, who had brought his fledgling aircraft manufacturing plant to Rhode Island from Connecticut. The new factory, largely financed by local businessmen, was built on an island that had served as a source of thatch for roofing since colonial days. The factory construction also included a causeway that connected the island to the mainland off Alger Avenue, a side street of U.S. Route 1.

The early decades of the twentieth century were times of cutting-edge discovery in the burgeoning field of aviation. The research and development was not unlike the early days of Apple’s and Microsoft’s discoveries in the late twentieth century. Gallaudet’s unique ideas have earned him a special place in aviation history, earned by his innovative designs that were among the forerunners of modern military seaplanes. But there was an added danger in those early, experimental days. Several test pilots were killed inGallaudet’s airplanes in the cause of advancing technology.

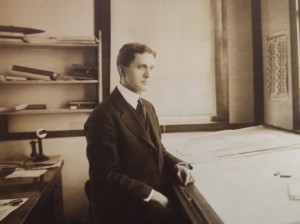

Edson Fessenden Gallaudet was born in Washington, D.C. in 1871, the grandson of Rev. Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet (a famed educator of the deaf for whom Gallaudet University is named). Edson was educated at Yale University and Johns Hopkins University. He began experimenting with aeronautics in 1897 while teaching physics at Yale. One of his revolutionary, warp-wing kite designs from 1898 is on display at the Smithsonian’s Air and Space Museum in the nation’s capitol. His superiors at Yale halted his experiments claimingthat his so-called far-fetched ideas did not reflect well on the university. So Gallaudet left teaching and moved to Dayton, Ohio, where he worked briefly with Orville and Wilbur Wright, who used Gallaudet’s warped-wing design for their 1903 Kitty Hawk flight. By the end of the first decade of the twentieth century, Gallaudet had opened an engineering firm in Norwich, Connecticut. It was there, in 1908, that he built his first aircraft. Gallaudet had earned his pilot’s license in 1911 and conducted some of his own test flights until he was injured in a crash.

In 1914, he patented a radical propulsion system called the Gallaudet Drive. It featured a four-bladed propeller mounted between the wings and tail. A metal drum surrounded the propeller and formed a key structural element for the fuselage. A complex arrangement of gears in the drum connected to twin engines mounted side-by-side behind the pilot and forward of the propeller with only the most efficient portion of the blades exposed to the airstream. Gallaudet claimed this design increased propeller efficiency by almost ten percent, a significant advance in those days.

In 1915, Gallaudet managed to convince the U.S. Navy that he was onto something. The Navy awarded him a $15,000 contract to build his Model D-1 seaplane, a large (for the times) two-seater with a 56-foot fuselage and a 44 foot wingspan. The main float was under the fuselage between two wingtip floats. The first flights, from the Gallaudet factory on the Thames River, were marred by a series of accidents. Re-designs boosted expenses to $40,000, well above the Navycontract. In his efforts to find additional financing, Gallaudetwas forced togive up control of the company, although he did retain the title of president. By 1915, hoping to obtain more orders based on the Navy’s satisfaction with the D-1, he decided he needed a larger plant.

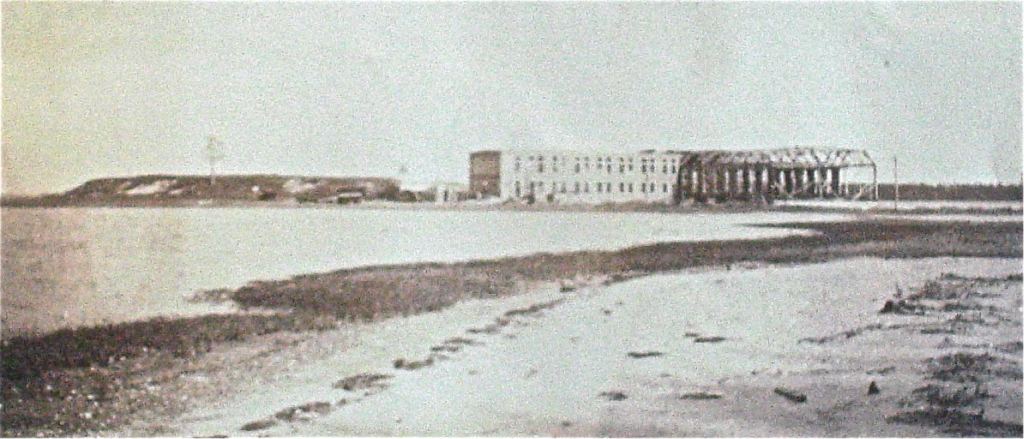

Gallaudet secured financing from a group of Rhode Island investors on the condition that he locate his new factory to Chepiwanoxet Island in Warwick. A large plant building was soon completed and in operation by 1916. The plant’s administrative office was housed in a handsome cedar shingle building that still stands at 4332 Post Road in Warwick and now serves as the office of a local real estate firm. It is the only remaining building of the Gallaudet facility (although there are remnants of foundations here and there on the island and a few pilings rising along the shoreline). Gallaudet renamed his company the Galluadet Aircraft Corporation in 1917.

Gallaudet and his team faced a similar problem in Rhode Island that they had in Connecticut: winter freezes on Greenwich Bayprecluded testing during the coldermonths.Accordingly, as winter approached, the planes were sent by rail to a U.S. Navy facility in Pensacola, Florida, where the test flights were conducted. Gallaudet’s D-1 and other airframes built in the factory were crated and trucked across a man-made, 150-foot causeway to the mainland and then west to the East Greenwich train station for shipment (some frames were also shipped via seagoing barge from a landing beside the factory). The New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad ran beside the factory property, and plans were drawn for a siding at the plant but it was never completed.

Gallaudet Aircraft factory under construction, around 1915. Note the absence of trees on the hill and low lying location of the factory, making it susceptible to storm-surge flooding (Neil Williams Ross Collection)

Only one D-1 was built and flown. But much was learned from this unusual craft. The Navy disassembled andreturned the plane to Rhode Island for numerous modifications. However, it never flew again. The final fate of the D-1, a beautiful and complex design, is unknown. It was likely scrapped after World War I.

Gallaudet moved on to more advanced designs. To keep the business going, he had joined other sub-contractors across the country in building floatplanes for the Navy based on designs of another aircraft pioneer, Glenn Curtis. At the height of World War I, the Warwick plantwas turning out one Curtis H-2S patrol-type seaplane a day. With the end of World War I, the military market quickly evaporated. Gallaudet continued to develop both civilian and military designs until aircraft production ceased in the early 1920s.

The Gallaudet Drive itself continued to draw interest. The U.S. Army ordered a new design, and Gallaudet gave them the D-2 for coastal defense using the drive. Twin 150-horsepower engines hauled a three-man crew: a pilot and a nose and anaft gunner. Two larger designs, the D-3 and D-4, were built before the war ended. The D-4 was intended as a light bomber for the Navy, capable of speeds in excess of 120 miles per hour and able to climb to 7,700 feet in ten minutes.

The D-models continued to beplagued by crashes that were frequently fatal to their test pilots. One well-recorded accident occurred on June 11, 1918, when another aviation pioneer, pilot Jack McGee, crashed into the waters off Warwick’s Goddard Park on Greenwich Bay. He was Rhode Island’s first aircraft fatality. McGee, a flamboyant flyer, had survived a dozen previous crashes. He was flying an aircraft that had just come off the Gallaudet factory line that morning when he dipped low over the water, caught a pontoon on a swell in the bay and flipped the plane over. Trapped in the wreckage, McGee drowned before rescuers could extricate him. No other D-types were ever flown.

Gallaudet developed numerous plans for seaplanes, land planes, fighters, bombers, and even an airliner. At least two of those designs started construction but none were completed after World War I.

A Gallaudet D4 seaplane after landing on the water in Narragansett Bay, with Goddard Park shoreline in the distance. Note the four-blade propeller behind the wing that rotated around the plane’s fuselage (Neil Williams Ross Collection)

In 1920, the Navy unveiled plans for a trans-Pacific flight using a 160-foot wingspan triple-wing flying boat powered by nine 400-horsepower engines using the Gallaudet Drive. The 6,200 mile trip from San Diego to Manila, with refueling stops in Hawaii, Wake Island and Guam, was set for late summer of 1921 or early spring of 1922. The fuselage and wings would be built at the Philadelphia Navy Yard and the three-bladed propellers by the American Propeller Company in Baltimore. Gallaudet’s Warwickfactory was contracted to build the engine nacelles and the gear drives connecting systems of three engines to a single propeller. These elements were completed and tested at the plant.The assembled nacelles, engines, gear systems, and propellers were shipped to the Navy by barge. But, before the plane itselfwas finished, budget cutbacks terminated the project. Gallaudet’s team continued to develop innovative aircraft designs but none of them were sold to the armed forces.

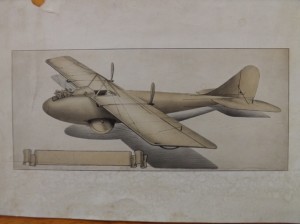

The company was forced into other projects. Gallaudet took advantage of the tremendous public fascination with flight and came up with an unusual twin-pusher prop sport plane with a pair of 18 horsepower engines called the Chummy Flyabout.

The little two-seater, built in the Warwick factory, was priced at $3,500, a hefty sum for the day. Ann Holst, owner/curator of Clouds Hill Victorian Museum in Warwick, whose mother Nancy by coincidencewas a pilot and whose grandfather, Philip Allen, Jr., was on the Board of Directors of Gallaudet Aircraft, has retaineda significant amount of material about Gallaudet’s ventures, among which is a 1919 advertising flyer for the Chummy. The glossy marketing brochuresuggested the planecould “be flown to the golf or country club and landed on the fairways.” Readers were tempted with “the joy of flying is to be had for the asking” and “weekend trips to neighboring estates.” Owners could fly “around the ranch or commute to the office by air.” A newspaper advertisement offered the plane as an alternative to courting by automobile and suggested “imagine calling for your young lady in a Flyabout and soaring above the clouds.”

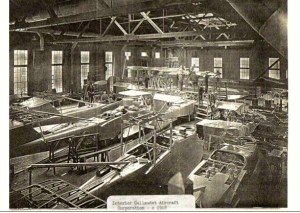

Aircraft under construction at the Gallaudet Aircraft manufacturing plant at Chepiwanoxet in 1918, intended for use in World War I. The aircraft could be the Gallaudet Battlecruiser Seaplane, with a forward gunner designed to attack German U-Boats (Neil Williams Ross Collection)

The Chummy was only eighteen feet, seven inches in length, with a 33-foot wingspan. The cockpit was a tight fit for two adults. Either or both of the air-cooled engines could power the twin 48-inch props. The whole plane weighed only 600 pounds empty (the literature does not indicate how much weight it could carry). Gallaudet’s company even offered to provide plans for a complete aviation club, including flying lessons, hangars, fueling station, tools, and a support staff. But only a handful of the little planes were ever built.

By 1923, the company’s aircraft business had run dry. The following year, Edson Gallaudet retired and the aircraft assets were sold to Major Reuben H. Fleet, a West Coast native who had resigned his Army commission in the post-war cutbacks to enter private industry. He had joined Gallaudet Aircraft in 1922 as plant manager and on Gallaudet’s retirement, Fleet used his own connections and personal resources to form the Consolidated Aircraft Company, which acquired the small aircraft manufacturer, Dayton-Wright Company of Ohio. Consolidated picked up the Gallaudet contracts for twenty TW-3 trainers, continuing to use the Gallaudet plant at East Greenwich until 1924, when aircraft production was moved out-of-state, ultimately to California.

In the 1930s, Consolidated produced the first of thousands of the famous Catalina flying boats, the PBYs that saw service world-wide during and after World War II. It is possible, though no firm evidence exists, that Fleet drew partly from his experience with seaplane construction at Gallaudet as he evolved the concept of the Catalina. Legions of the PBYs returned to Narragansett Bay. Based at theQuonset Point Naval Air Station, they flew many anti-submarine patrols along the Atlantic coast. Thus, the military seaplane presence on Narragansett Bay came full circle.

In a final effort to keep the company alive in the 1920s, Gallaudet Aircraft’s name was changed to GACO. To survive, the firmbegan making rollers for textile yardage and paperproducts for Rhode Island’s textile industry, and even tennis racquets and balsa-wood fabric-covered surfing boards (the ancestors of today’s water skis). The entire business went dark in the mid-1930s, a victim of the Great Depression.

Much of the original Gallaudet complex (with the exception of the administration building) was destroyed in the 1938 hurricane. Just before World War II,East Greenwich resident Jack Riley opened a small industrial wood products company in one of the surviving buildings. A part of the remaining plant facilities was leased to boat builder Bill Dyer who began building his famed Dyer Dink sailboats at Chepiwanoxet (the company later moved to Warren, R.I., where it still operates). In 1946 the Amtrol Company started manufacturing water pressure control tanks in one of the empty seaplane buildings. Hurricane Carol wiped out all the buildings housing those facilities in 1954. A small recreational marina survived on the site until Hurricane Donna wiped out everything left in 1960.

Drawing of the Chummy Flyabout, the 1919 “sport model,” from a Gallaudet marketing brochure (Ann Holst Collection)

The Bostitch Company, known for its stapling equipment, operated a factory in East Greenwich for many years and used the shoreline in the area of the factory as a dump for manufacturing scrap. Chepiwanoxet resident Neil Ross spent his childhood years in “Chepi”. “I remember my friends and me scrounging through the Bostitch leavings looking for treasures,” he recalls. “We’d find staple bottoms and pieces of iron blocks. From another plant on the island, we’d pick up cast off textile spindles. They were like small megaphones and we’d use them as horns and to whistle through.” Traces of the metal debris can still be found along the waterline. Today, the land abuts a quiet, bayside residential neighborhood.

The area that once was home to a pioneering aircraft initiative was designated in 1994 as the Chepiwanoxet Wildlife Preserve and Park by the City of Warwick. The area is currently under the management of the Warwick Conservation Commission and the Chepiwanoxet Neighborhood Association. Signage at the site commemorates the property’s history and local efforts continue to restore and maintain the site for the enjoyment of future visitors.

Gallaudet administration staff at the office building (still standing) at the corner of Post Road and Alger Avenue, Chepiwanoxet, Warwick, R.I. (Ann Holst Collection)

What became of Edson Gallaudet? After a quiet retirement, he died on July 1, 1945, at age 74, and was buried in the Gallaudet family plot at the Cedar Hill Cemetery in Hartford, Connecticut. Along with pilot Jack McGee, he has been inducted into the Rhode Island Aviation Hall of Fame.

[Banner image: Unused Gallaudet Aircraft brass nameplate that would have had a date and plane number added (Neil Williams Ross Collection)] [The author wishes to extend a special note of thanks to Neil Williams Ross and Ann Holst for their valued contributions to the above article, especially for the photographs and anecdotes associated with the Gallaudet Aircraft factory and Chepiwanoxet Island.]

Bibliography

Personal Interviews and Reviews of Family Papers and Photographs with Ann Holst, Curator, Clouds Hill Victorian Museum, Warwick, Rhode Island, April 2014

Neil Williams Ross, “Chepiwanoxet History: Anecdotes, Memories of Its Island, Beach, Land, People,” Chepiwanoxet Press, Rhode Island, 2004 (anecdotes and selected photographs used with permission)

“US to Send Giant Seaplane Across Pacific,” Wichita Beacon (Kansas), April 19, 1921

“The Might Have Been Story of Gallaudet,” Providence Sunday Journal Rhode Islander Magazine, November 29, 1959

“The Call of the Clouds,” Gallaudet Aircraft Corp., East Greenwich, R.I., marketing brochure for Chummy Flyabout, 1919, from the collection of Ann Holst

Gallaudet News Employee Newsletter of the Gallaudet Aircraft Corp., East Greenwich, R.I. Vol. 1, No. 9, January-February, 1922, from the collection of Ann Holst

Edson Fessenden Gallaudet:” en.wikipedia.org/Edson_Fessenden_Gallaudet

“Gallaudet Military Tractor”” aviastar.org>VirtualAircraftMuseum>USA>Gallaudet

“Gallaudet D-1:” earlyaviators.com/ebjorkl1.htm