It was, the Providence News reported in its May 13, 1924, edition, “[t]he greatest political battle in the State of Rhode Island since the Dorr Rebellion.” Not surprisingly, its roots were in the unfinished business left by the incomplete settlement of the Dorr Rebellion.

By the end of the first quarter of the twentieth century, Republicans had been in control of Rhode Island state government for more than seventy years; but in 1924 that control was challenged by Democrats in the state senate. While it would take another decade before control was finally wrested from the Republicans in what is often referred to as the Bloodless Revolution of 1935, the Democrats gave it a valiant try in 1924. Republicans held a slight edge in the senate with twenty senators while Democrats had eighteen; however one independent, Jesse Hopkins of Coventry, often sided with the Democrats, thus causing a near even split on many votes. Presiding over this chamber as ex officio President was Lt. Gov. Felix Toupin, a Democrat. It had been a long time since Democrats had come so close numerically to matching Republicans in the senate, and with the advantage of Toupin running the show the opportunity for pushing through Democratic-sponsored bills became a strong possibility. Adding to the situation, Governor Flynn was also a Democrat and there was little chance for a veto of Democratic-sponsored legislation.

Rhode Islanders had long been represented in the senate under a “rotten borough” system. Each town had but one senator regardless of its population, thus many small rural southern towns had the same representation as the larger industrial towns in the northern part of the state. For three quarters of a century this disproportionate system remained intact and virtually impossible to change. The Republican Party, firmly in control of state government, was not desirous of seeing change. The rural towns preferred the situation as it stood since they had nothing to gain and everything to lose if representation was proportional. Lastly, the wealthy industrialists of the state, nearly all Republicans, were disinclined to see their employees have much say in the running of government because, after all, any portended labor reform laws as a result of an expanded working class electorate would affect the industrialists’ bottom line.

In 1924 the Republican Party was defiantly not the party of the people. For three quarters of a century many questionable laws were enacted that favored big business. Corruption was the norm and vote buying was commonplace. The poster child for corrupt government was Charles “Boss” Brayton, a protégé of Senator Henry Bowen Anthony. Brayton never held political office but from his office located in the state house he directed the workings of state government. All appointments to state positions were made under his oversight. After Brayton died in 1910, control of state government fell to the Republican State Central Committee chairman; in 1924 that position was held by William C. Pelkey.

The Republican-held majority in the senate was ever so slight.[1] If for any reason a Republican senator were absent for a vote on a Democratic-sponsored bill it would pass. With Lt. Governor Toupin running the senate it was certainly possible to quickly push a vote through the chamber. Without a Republican in the governor’s office there was no hope for a veto, so it’s no wonder Republicans were reluctant to leave the senate chamber, even for a bathroom break. The best policy for the Republicans was to insure no Democratic-sponsored bill ever left any of the Republican-controlled committees. Democrats in 1924 favored several bills including a forty-eight-hour law, a call for a constitutional convention, and abolition of property qualifications.

The January 1924 session of the senate would prove to be a contest of wills with Democrats pitted against Republicans, when Robert E. Quinn (1894 – 1975), a first-term senator from West Warwick, took on the leadership role for the Democrats.[2] Just thirty years old, he was an able leader and a formidable foe. In an interview given nearly forty-eight years later he reflected on the 1924 session and noted, “We were confident that we were right, that our course was right. In other words, we knew that the so called ’rotten borough’ system existed in Rhode Island where West Greenwich with 485 people had a senator and Providence with 275,000 people had a senator. In other words the ‘rotten borough’ system meant that the old Republican organization, through towns like West Greenwich, Exeter, Richmond and New Shoreham, and Little Compton, and so forth, controlled the state of Rhode Island . . . .”[3] Quinn, later known as Fighting Bob, was determined to take on the Republicans in order to have his bill on constitutional reform sent before the people. “Actually the major basis for our attack was the refusal of the Republican judiciary committee – of course, they were in control of all the committees – but our attack was directed against the judiciary committee for its refusal to report out for a vote. Now we weren’t demanding passage of the resolution although nothing could be fairer. This was simply to ask the people whether or not they would like it to. But we weren’t insisting upon them passing it. We were insisting that they bring it out to the floor for a vote. And they refused it. Then we started to put the pressure on because frankly we felt . . . that we were younger, physically we were abler, I’m not sure we were.”[4]

The Democrats had been repeatedly frustrated by their inability to get any of their bills out of Republican controlled committees and onto the senate floor for a vote. Of special importance was Quinn’s bill that called for a constitutional convention and that had been tied up in the judiciary committee. In January an attempt to get senate rule #38 amended to allow a bill to be reported out of committee upon the request of any ten members failed to pass.[5] The Democrats next planned to force movement of their legislation by other means. The plan devised by Quinn and his associates was simple: they would bring the chamber to a standstill with a filibuster; no other state business would be processed unless their sponsored bills came out of committee. Lt. Governor Toupin would cooperate as the senate’s presiding officer by recognizing only Democrats to speak. Beginning with the session on January 9, 1924, Democratic senators took shifts speaking, often two hours each, reciting passages from various books including Shakespearian plays and the Encyclopedia Britannica. The Democratic reasoning was as they were younger and conceivably better fit than their Republican counterparts, they could easily outlast them. This was a gross miscalculation as the filibuster lasted well into June. After six months the filibuster had taken a toll; many senators were worn out both physically and mentally and tempers were short. The lack of air conditioning in the chamber added to the misery and, as the months grew warmer, the heat and air quality in the senate became stifling.

In early June there were signs the filibuster was causing strain on senators. The pro-Democratic newspaper the Providence News reported in a front-page story “Five Millions To Be Used To End Filibuster” The article noted “Because the political party in power – owned body and soul by the oligarchy of mill barons and their satellites – cannot beat down the demand of the people for full franchise rights, the money-bag dragoons are being sent against the supporters of orderly government, and what comes perilously close to rebellion is planned.” The article went on to say, “Rhode Island’s lawmaking branch of the government is to be taken from the people by the power of money – through the deliberate abandonment of the General Assembly. Without a quorum the courts would hold the legislature impotent.”[6] If money were to make a difference the Republicans had a decided advantage. Robert Quinn remarked that Republican Chairman Pelkey boasted he had $250,000 to use for Election Day. This far outweighed the Democratic war chest of $10,000. Certainly, with the moneyed interest of the state in the Republican corner, significant influence could be brought to bear. The newspaper article implied Republicans might abandon the General Assembly, and without the Republicans present no quorum was possible; however, senate rule #35 provided for just such a situation by allowing any seven members of the senate, by majority vote, to compel under the constitution and state law the attendance of the absent members. However, state law went only as far as the state line, and absent senators once outside of Rhode Island could not be compelled to return. It just didn’t seem plausible for Republican senators to collectively disappear, but difficult times called for difficult measures.

Adding to the woe was the fact no appropriation bills had passed the senate since the beginning of the year; an emergency bill before the senate in mid-June failed to pass thereby causing concern the state might not meet payroll. Neither senate Republicans or Democrats were willing to compromise; Rhode Island’s legislative government was effectively deadlocked with each side looking for a weakness in the opponent’s strategy. Patience had worn thin over six months of filibustering and angry exchanges—something would have to give. The breaking point finally came in mid-June.

On Tuesday June 17th angry words turned to deeds. After fifty-five days of filibustering, everyone in the senate was tired. Encouraged by the local press calling for citizens to go to the state house in support of their senators, the corridors leading to the senate chamber as well as the senate gallery were filled with spectators—one account estimated the number at 2,000 people.[7] Nerves were raw and it did not take much to set off a series of angry outbursts; the first occurred when the afternoon session opened with Republican “plug-uglies” physically blocking Lt. Gov. Toupin’s entry into the senate chamber.[8] With Toupin unavailable, Arthur Sherman, the Republican President pro tempore, took control and called the session to order. Sherman directed the clerk, James Dooley, to call the roll. Quinn, detecting the Republican attempt to take control, jumped from his seat in an effort to grasp the roll from the clerk’s hands but before he could do so, Republican Secretary of State Ernest Sprague tackled him.[9] Democrat and Republican senators erupted into a free-for-all, and spectators (both male and female) joined the fray. The melee was too much for the Capitol police to handle and finally the Providence police, using more than a dozen officers armed with riot guns, were brought in to restore order in the chamber. As the room was being cleared, Governor William Flynn entered and addressed the senators, reminding them of their duties. He also rebuked sheriff Andrews of the Capitol police—a Republican appointee—that it was his sworn duty to uphold the law and obey the presiding officer (Lt. Gov. Toupin). Andrews and his men had been accused of having sided with the Republican senators during the fight.[10] Later that afternoon the senate finally returned to its business. Newspapers that had already issued their final editions had to issue “Extra” editions to cover the afternoon developments.

Following the brawl the senate went back into session and stayed in session around the clock. After more than twenty-eight hours of continuous filibustering, another violet outburst developed just outside the senate chamber. At around six o’clock in the evening of June 18th, Quinn wrapped up his turn as filibuster speaker and took a break outside the senate lobby in order to get some fresh air and while he was there a fellow senator warned him that Jack LeTendre was “carrying a rod” and was in the State House looking for him.[11] At that moment Quinn turned and was sucker-punched by LeTendre. Quinn, no shrinking violet, went on the attack and pummeled his attacker. Quinn’s somewhat humorous account of the event is quoted here:

He must have weighed around 250 pounds. He was a big man. And, of course, I always weighed about 160, I would say. I was relatively small. But we had begun and, you know I had talked, I guess, a couple of hours. I think John McGrane was talking. He talked a couple of hours and so forth. And I had gone out through the Senate Lobby. From the Senate chamber you went into the hallway, really, that ran from one side of the building to the other. And then there was the Senate Lobby where the big easy chairs were there for the convenience of the Senators lined up along the wall. And then it went out onto the stone porch. There were big windows where you could walk in and out, you know. They were, oh I don’t know, fifteen feet high, I presume they are there. In any event, I had gone out through one of those windows, was sitting out on the balcony and getting a little fresh air and a little rest and John Power who was then the senator from Cumberland [sic]; he was the representative of one of the textile unions, I think. But he was the senator from Cumberland anyway. As I came in from the window to go back toward the Senate Chamber, Powers stopped me and said “Hey, you better look out.” I said “Well, what’s the matter, John?’ “Well.” He said LeTendre carries a rod, you know.” So I said, “Well, what do I care what he carries?” I don’t give a damn about LeTendre who had apparently had been looking over my shoulder as I sat out on the stone porch there with his hands twitching according to what Senator Powers told me was ready to grab me and drop me over the railing about 15 or 20 feet below, took a swing. I had come back and was along that line of chairs where the senators sat down, smoked and so forth. He took a swing at me and he hit me on the cheek . . . . He hit me on the cheek and knocked me back toward one of the chairs so that I really got a kind of spring. In other words, I backed on the chair, but that gave me a purchase [chance] to spring forward and he had a cigar in his mouth and I hit him back. I knocked the cigar right down his throat. And I knocked two of his front teeth out.[12]

As bad as the behavior had been over the previous two days it was nothing compared to what happened on Thursday morning, June 19th. During the morning session a bomb went off near the feet of the senate president. While the bomb was not of the percussive type, it sent up a cloud of bromine gas sufficient to clear the chamber and cause some senators to become ill.[13] In the confusion of the moment the senate chamber was emptied; Republicans gathered in several interconnecting committee rooms while the Democrats gathered in the halls. Two senators, Arthur Sherman of Portsmouth and William Sharpe of East Greenwich, both Republicans, were sent to Rhode Island Hospital. Once the senate chamber was cleared Lt. Gov. Toupin called the senate back to order. However, all the Republicans except one stayed locked in the committee room and refused to come out. Lt. Gov. Toupin, on warrant, requested the sheriff to bring in the missing senators but they refused. The Republicans claimed they were too sick to attend. The Providence News noted, “The Democrats are not sick, but 19 Republicans are so sick that a doctor now says that they can’t be brought in here.”[14] The one Republican not locked in the committee rooms was Henry Evers of Cranston who was assigned to sit in session and insure no quorum was met. After attempts to get the Republicans back into the senate chamber failed, a recess was called. The following day word was sent that the Republicans had left the state and were at a hotel in Rutland several miles outside of Worcester, Mass. The placing of the bromine bomb served its purpose; the filibuster came to an abrupt end.

On the day following the bomb incident the Providence Journal offered a $1,000 reward “For Information Leading to the Arrest and Conviction of the Person or Persons who placed Bromine Gas in the Rhode Island Senate Chamber.”[15] It was generally known that the bomb was placed by one of the thugs from a Boston gang on orders from William Pelkey, Chairman of the Republican State Central Committee, but as the Journal was a Republican newspaper it didn’t hurt to raise some doubt in the public’s mind regarding the perpetrator.[16]

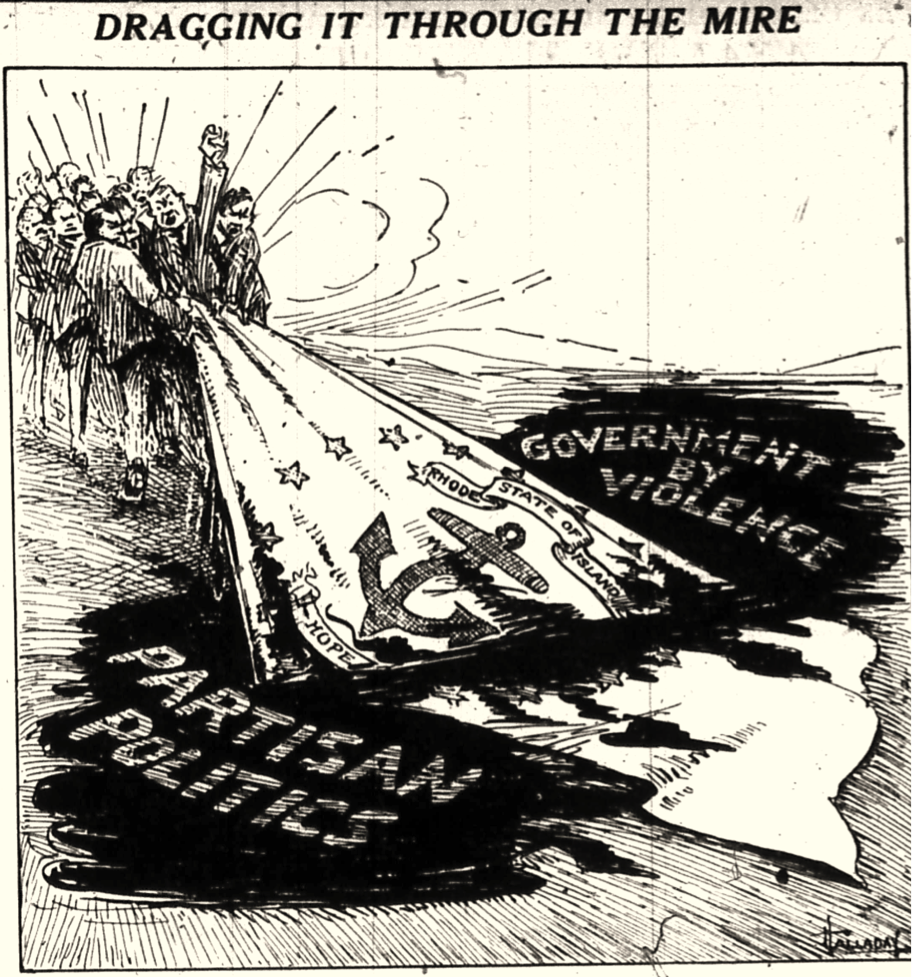

The senate impasse had it consequences. Without Republican senators present, there could be no quorum and without a quorum no business could be conducted by the General Assembly. Neither Republican nor Democratic agendas could be realized. The state’s reputation took a hit as national newspapers picked up the story. Rhode Island’s paralysis in state lawmaking would last for the remainder of the year. Milton Halladay, the renowned Providence Journal cartoonist, depicted the situation best with his cartoon “Dragging It Throughthe Mire.”

For the time being Democrats held sway in the state house, but their position would be short lived and most would be turned out of office in the November elections. The Republicans spent the remainder of 1924 at the Hotel Bartlett in Rutland, Massachusetts, returning to Rhode Island only after the New Year. Judging from an image of this resort hotel, taken around the time of the Republicans’ stay there, it appears that their exile was not much of a hardship. [17]

All efforts by the Democrats to wrest control of state government came to naught as a result of the 1924 November election. Not only did the Democrats lose both the governorship and lieutenant governorship, but they were also resoundingly defeated for representation in the General Assembly. Most of the seats won by Democrats in the 1922 election were lost in 1924; a phenomenal sixty-eight percent of all Democrats were turned out of office. In the senate, Democrats retained only six of their nineteen seats, including the one independent seat gained in 1922. To quote Robert Quinn, “We just got murdered”.[18] Only six towns (Burrillville, Central Falls, Cumberland, Jamestown, Woonsocket, and West Warwick) returned a Democrat to the senate. In the house, Democrats lost a total of sixteen seats with only Burrillville and West Warwick retaining all Democratic representatives. Just as the electorate had turned out Republicans in 1922 following the violent suppression of textile mill strikers in both the Blackstone and Pawtuxet river valleys, it now expressed its displeasure with Democrats following the state house antics of 1924. It would take another eleven years before Democrats finally gained control of state government as a result of the Bloodless Revolution in 1935.

[Banner image: Headline from the Providence News, June 19, 1924. The headline reads, “Republicans Plant Poison Gas Under Toupin’s Chair” (Russell DeSimone Collection)]Bibliography

Brady, Hillary. “Fistfights and filibusters: the 1924 Rhode Island Senate.” Providence Journal, June 20, 2014.

D’Amato, Don. “Bromine Gas Bomb in the Senate.” Old Rhode Island, Vol. 2, Issue 9 (October, 1992).

Levine, Edwin. Theodore Francis Green: The Rhode Island Years, 1906 – 1936. Brown University Press, 1963.

McLoughlin, William. Rhode Island – A History. W.W. Norton & Co., 1978.

Patten, David. Rhode Island Story, Providence Journal Co., 1954.

Quinn, Robert E. interview, July 14, 1972. Interviews were taken and transcribed by Matthew Smith, Providence College archivist, during the Judge Robert E. Quinn Interviews on Mid-20th Century Rhode Island Politics. See http://digitalcommons.providence.edu/quinn_interviews.

Spencer, Terry D’Amato. “When Rhode Island politicians became the ‘laughing stock of the jazz age’.” Series of three articles in the Warwick Beacon, July and August, 2013.

Endnotes

[1] The 1924 House of Representatives was also a near split; The Republicans had a slight edge of two votes. There were 51 Republican representatives compared to 48 Democrats and 1 Independent. [2] In 1924 senators were in the second year of their term. Many of the reform policies Democratic members proposed in the 1924 session were the same as those of 1923. While there was much hostility between the parties in 1923 it was the 1924 session that saw the worst of the legislators’ behavior. [3] Quinn interview, July 14, 1972, transcript Part I, page 20. [4] Quinn interview, July 14, 1972, transcript Part II, page 5. [5] Rule 38 allowed in part for a bill to be called from any committee with a two-thirds vote of all members of the senate or upon a majority vote after one day’s written notice. [6] Providence News, June 3, 1924. [7] See Providence News, June 17, 1924, both final and extra editions. [8] Plug Uglies was a term originally used in the late 1850s in reference to a gang of street toughs in Baltimore, Maryland, who were known for their political fighting during election time. In 1924 the Democratic press used this term to describe the Republican hired toughs looming in the halls of the state house. [9] David Patten writing in 1954 stated it was Willis Drew, the Republican senator from Barrington, that grabbed Quinn but the Providence News reported at the time it was Secretary of State Sprague that grabbed Quinn and Drew came to Sprague’s aid to hold Quinn down. [10] The senate sheriffs had been accused by the Democratic press of joining in the fight alongside Republican senators in beating up Democratic senators. There is some credence to this claim as the sheriffs were all appointed to their positions by the Republican controlled government. This was not however the first time that the deputy sheriffs had been warned by the governor. See “Orders Of Toupin Must Be Obeyed, Says Governor,” Providence News, May 13, 1924. [11] John “Big Jack” LeTendre (1878 – 1946), was a former Republican representative from Woonsocket, having served in that capacity from 1915 to 1919. His official biography as noted in the 1919 issue of the Rhode Island Manual lists him as an automobile dealer and garage manager. He was also associated with known members of organized crime, having once been involved with Meyer Lansky and Frank Costello in Club Boheme, a Florida casino. He met an untimely death being gunned down in his car near his Woonsocket home on April 23, 1946. The local newspaper accounts referred to him as a race track plunger. [12] Quinn interview, July 19, 1972 pages 1 through 5. [13] The bomb may have also had a psychological effect, coming so soon after World War I and its horrors of gas warfare. It’s plausible the senators, not knowing what type of gas was used, would have been concerned for their health if not their lives. [14] Providence News, June 19, 1924. [15] Providence Journal, June 20, 1924. [16] On August 4, 1924 William Pelkey, John Toomey (a fight promoter from Johnston who called in the Boston gang of thugs) and William ”Toots” Murray ( a member of the Boston gang responsible for setting off the bromine bomb) were indicted by a grand jury. The two material witnesses for the government were Thomas Lally and Matthew McGovern, both members of the for hire gang of Boston thugs that Pelkey engaged to break up the filibuster. When the trial began in early October, the prosecution could not produce either witness; conceivably the Republican machine bought them a vacation somewhere nice. Without the two main witnesses the case was dismissed. [17] The cost of this venture was borne by the Republican Party but Frederick Peck, a wealthy businessman and one of the state’s GOP Big Six, defrayed some of the cost. [18] Quinn interview, July 19, 1972, Part 2 page 10.