Many think that the acquisition of Coasters Harbor Island in Newport by the United States Navy, for use as a naval training station, was a simple, linear process that arose from the Navy’s experience in Narragansett Bay during the Civil War when the United States Naval Academy was temporarily relocated to Newport. In reality, it was a bit more complicated and required a concerted effort by the State of Rhode Island to sell the idea to the Navy. Throughout the history of “Naval Training Station Newport,” not only have there have been expansions, but also contractions that threatened the existence of the base. This article will look at the original reason for creating the Naval Training Station—training new recruits—from its establishment until the Navy shifted the recruit training function to Bainbridge, Maryland, in 1951.

The State of Rhode Island tendered to the federal government a preliminary offer of a location for the establishment of a training school for boys on March 8, 1878. At the same time, the state appointed a commission to promote Newport as the site, consisting of Charles C. Van Zandt of Newport, Augustus O. Bourn of Bristol, and George Lewis Cooke of Warren.[1] There was another site being considered near New London, Connecticut. The selection process did not move quickly and both sides had their advocates at the various levels of government. Transparency was not the watchword and deals could be made. After all, the selection of a site involved jobs, an increase in property values, and a long term investment by the United States Navy in the future of the state that was selected.

When Rhode Island learned of a federal appropriation in September 1880 of $20,000 to be spent on “certain building improvements incidental to the use of a Naval Training School,” officials sensed an effort by the New London proponents to create a fait accompli. The commission of Van Zandt, Bourn, and Cooke wrote to the Secretary of the Navy, Richard W. Thompson, requesting that all funding be held until the appointment of a committee of naval officers interested in the success of such a training establishment could make a formal recommendation to guide the Navy’s decision. Their letter went on to contrast the many advantages offered by Narragansett Bay versus the many detrimental factors associated with the selection of New London.

Considering the politics surrounding the establishment of the training school, Thompson, on November 27, 1880, ordered the establishment of a committee of naval officers to review the facts, conduct site visits, and recommend a location. The committee was composed of Commodore Earl English, Chief of Bureau for Equipment and Recruiting, Captain Samuel R. Franklin, Captain Stephen B. Luce, Captain Ralph Chandler, and Lieutenant F. E. Chadwick. The officers gathered on board the USS Powhatan, then at the Naval Station at New London, Connecticut, and assigned to their use.

The committee “after careful examination” issued its written report on December 4, 1880. The seven-page, handwritten letter listed six disadvantages for the site at New London:

- – The distance from any large expanse of water being nine miles

- – The lack of a place for gunnery practice in the vicinity

- – The likelihood of the river’s becoming frozen, hindering all operations and the transporting of supplies from New London

- – The expense of maintaining communications with New London

- – The impossibility of training apprentices in boat handling on the river, whether rowing or sailing

- – “The cheerlessness of the situation, the monotony of the life due to the seclusion of the place and its gloomy aspect in winter,” which had led to the loss of 120 boys to desertion and discharge during the winter of 1879-1880.

Rhode Island took a different approach to the offering of a site. It offered any land on Narragansett Bay that might fit the Navy’s needs. After looking at several sites, the committee settled on Coasters Harbor Island as being admirably adaptable to the purpose, noting the following advantages:

- – Separated from the mainland but accessible via a causeway with a drawbridge, offering good communication or isolation, as desired

- – The finest water within three miles of the open ocean, with a harbor accessible in all winds

- – Well located for gunnery exercises, either within the bay or while underway on the open sea

- – Access to the Naval Torpedo Station at Newport and instruction in the use of torpedoes

- – A climate that was cool during the summer and mild in the winter

- – Easy access to ports of New York and Boston for the transfer of recruits

No disadvantages were noted. With the report in hand, on December 16, 1880 the Navy Department accepted the offer of the State of Rhode Island.

At the same time, forces in Rhode Island continued to put all of the necessary pieces in place so that when called to act, they would be ready. One such action was a vote held in the City of Newport on December 22, 1880, where by a majority of affirmative votes, a proposition was approved to cede Coasters Harbor Island to the State of Rhode Island, which would then cede the property to the Federal government for use as a United States Navy Training School.

The stage was set for the General Assembly of Rhode Island to cede jurisdiction over Coasters Harbor Island and all buildings and appurtenances thereon.[2] This was accomplished on March 2, 1881. Formal notification was given by then-governor Alfred H. Littlefield to then-congressman Nelson W. Aldrich (later U.S. Senator for Rhode Island for thirty years) in a letter of that same date. This was amended on August 7, 1882, stating that it was for use as a Naval Training Station.

One of the earliest known photographs of young apprentices. In the early years, apprentice boys could be as young as fourteen, which explains the small stature of some of the boys. It is also noteworthy that some African-Americans are shown as apprentices. (Naval War College Museum)]

The Navy Department permanently established a training school at Newport, calling it the Naval Training Station, on June 4, 1883. The following day, Secretary of the Navy William E. Chandler requested from Rhode Island’s governor a certified copy of the original deed or instrument dated March 2, 1881, stating that the City of Newport ceded to the State of Rhode Island said Coasters Harbor Island for the location of the Naval Training Station. The Secretary of State for the State of Rhode Island, Joshua M. Addeman, complied with that request in a letter dated June 25, 1883.

The wording of the letter led a question as to whether the ceding of ownership to the bridge and causeway were included in the 1881 action. The issue surfaced during the dredging of the waters between Coasters Harbor Island and the City of Newport which, in turn, required alterations to the causeway and bridge. The federal government had approved the appropriation for the work as it was in connection with the expansion of the Naval War College; however, the Corps of Engineers was unable to proceed when the question of jurisdiction came up. It was not until May 1891 before the General Assembly formally declared that it had been its intention to include those properties with the island. With that, the Navy Department then had to query the federal government on whether there was a necessity to get Congress to re-accept Coasters Harbor Island, including the bridge and causeway, or whether the original acceptance was sufficient since the original intent of the General Assembly was to include the property. It was determined that the official title of ownership for the property was established by the 1881 ceding of the property.

As originally envisioned, there were to be 750 young men (in the early years, some were still boys) brought in annually for a ten-month curriculum. The program was known as apprentice training and it was the mission of the Naval Training Station to train and educate raw recruits in a sufficient quantity to man U.S. naval warships. Toward that end, eight months would find the recruits on a ship and the remainder of the time they would be occupied with training ashore. It would not be until 1887 that training was accomplished entirely on shore. Still, recruits continued to live aboard ships in the harbor. Construction of facilities began in 1883 with the first barracks. Barracks A was not a dormitory and would be more correctly called a drill hall or gymnasium. It was lost to fire in 1906.

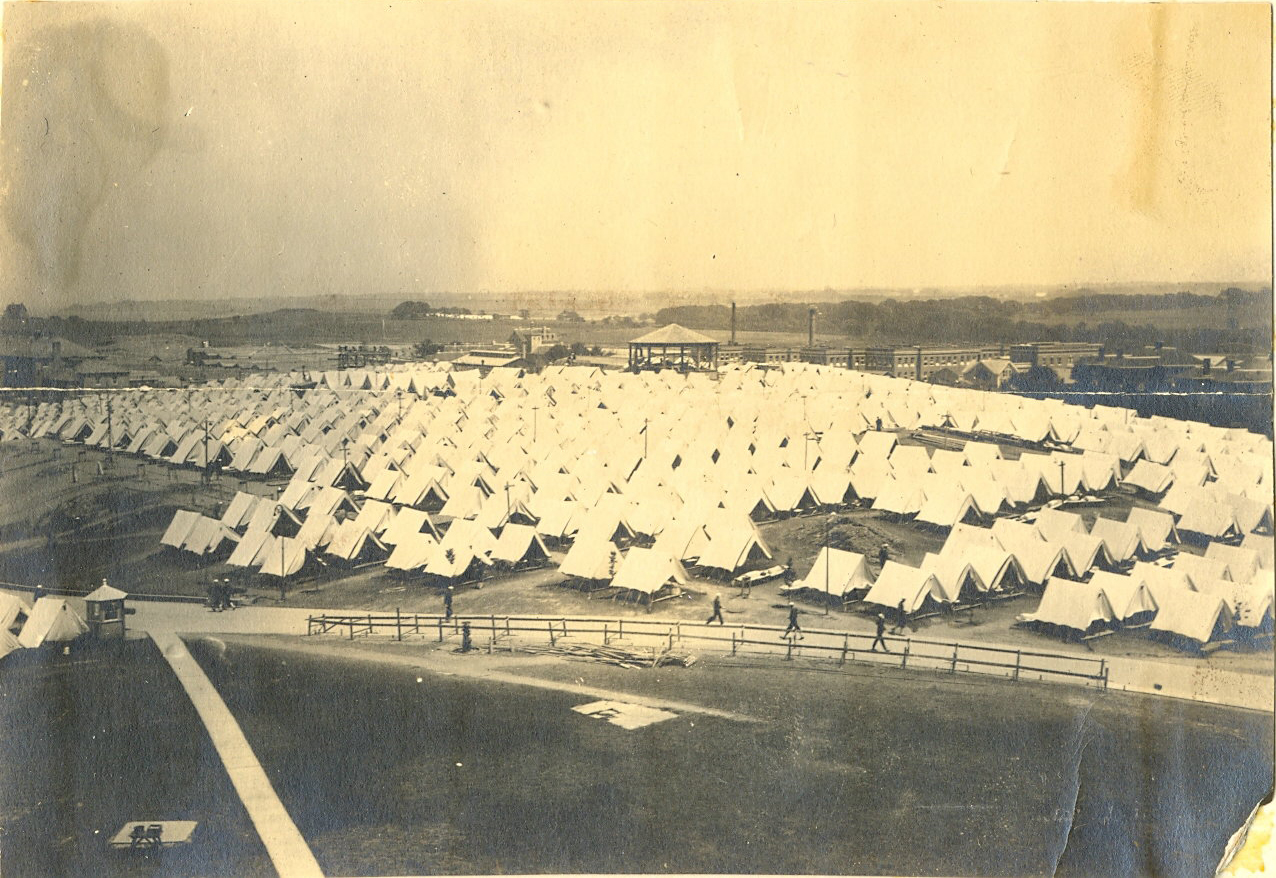

The first actual dormitories for recruits were Barracks B (1900) and Barracks C (1904). In addition to being dormitories, they were also used as training facilities.[3] A second Barracks A, erected in 1906-1909, consisted of seven two-story buildings, five of which were used as dormitories.[4] At times prior to World War I, whenever it was necessary to expand housing to meet the increase in the number of recruits, tent cities were created.

With the outbreak of World War I in Europe, the Navy began to expand the facilities on Coasters Harbor Island and began to use Coddington Point as well. Beyond the basic boot camp training, a Yeoman School, a Signal School, a Hospital Corpsmen Training School, a Commissary School, a Musician School, and a Firemen’s School were established. By the time the United States entered the war in 1917, the influx of new recruits and other students had required the erection of several thousand tents. In response, tar papered, temporary barracks and other temporary support facilities were constructed until more permanent buildings could be erected on Coddington Point. Most notable of the new buildings was a temporary mess hall that was built in fifty days and fed 5,000 men at each meal. In such facilities, the Naval Training Station trained, equipped, and sent to the fleet over 65,000 men during World War I.

Coddington Point’s expansion was the most dramatic as contracts were let in 1917 to 1918 totaling $4,500,000 for new barracks and other facilities to support the intended influx of 15,000 more men. Work began immediately but, with the Armistice being signed in November 1918, much of the work was cancelled. Without the projected influx of recruits, the completed buildings and the already installed equipment sat unused until 1920 when recruit training was shifted to Coddington Point to allow for the renovation of the barracks on Coasters Harbor Island. The renovation was completed in the spring of 1921 and the Coddington Points buildings were again unused.

With the arrival of the new fiscal year, there was a move in Washington to place Naval Training Station Newport into an inactive status.[5] Blaming the decision on declining recruitment and the cost associated with training recruits in Newport, the Navy was prepared to transfer all training activities, boot camp and schools, to Hampton Roads, Virginia. All matériel supporting training was to be made available for other stations. The station complement of personnel was pared to a minimum, in keeping with the loss of mission.

To meet a large influx of new recruits, the Navy chose to put the overflow into tents until temporary barracks could be built. This view of Coasters Harbor Island is to the northeast, with Barracks “C” or Sims Hall on the left and Barracks “A” to the right. The site today is occupied by McCarty Little Hall (Naval War College Museum)

Democratic Senator Peter G. Gerry of Rhode Island rose in defense of the Naval Training Station at Newport, and demanded an investigation into the basis for the recommendation to close the base. Evidence given to the Senate Committee did not stand up to scrutiny as the costs given were shown to be in error. Additionally, the Navy convened a Special Board on Shore Establishments, informally known as the Rodman Board for the senior officer, Admiral Hugh Rodman. In its final report it recommended that the Naval Training Station remain open. The Newport base was saved for the time being, but the eight-month closure was proof that its position was precarious and that other states coveted the economic benefits to be gained by its ultimate closure.

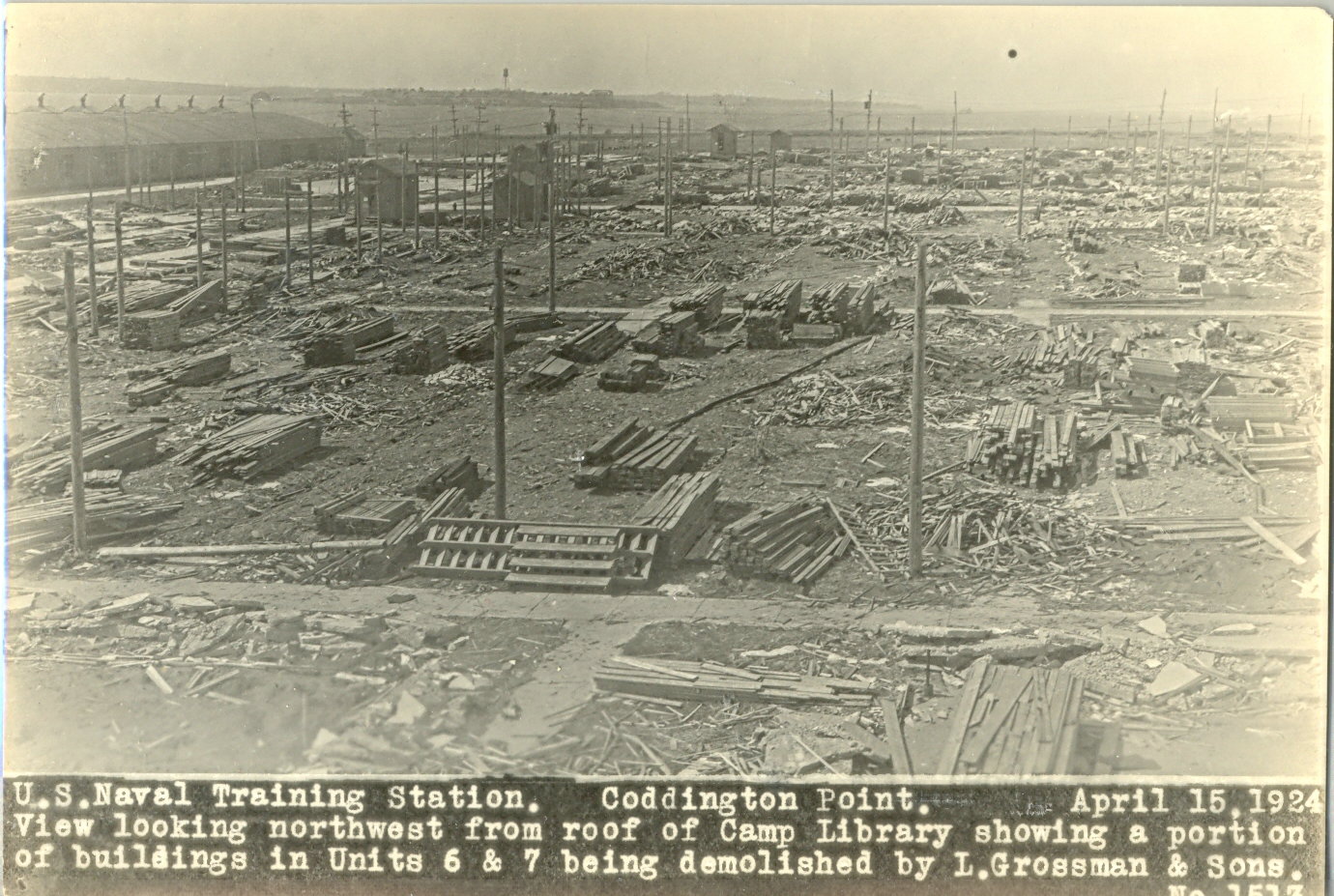

The one aspect of the Training Station at Newport that was not saved was the expansion to the Coddington Point side of the base. There were over 200 buildings, part of the war emergency camp built in 1917 and 1918, that were auctioned and sold in July 1923 for a total of $50,375. What had been a growing town quickly was reduced to foundations and connector roads as everything of value was stripped and sold, leaving few buildings. Coddington Point was then made into a rifle range with ranges of 200 and 600 yards.

As Hampton Roads was the primary competitor to recruit training on the East Coast and had already pulled away many of the schools previously established in Newport, it is interesting to note a study that was ordered by the Navy in 1927 to compare the rate or propagation of communicable diseases at Newport and Hampton Roads. The thirteen-page report submitted by Medical Corps officers gives an interesting look at the training methods and organization at the two training stations. Cleanliness was not a password. The buildings were built in ways that did not promote hygiene. Messing facilities would be located adjacent to wash rooms, sleeping quarters, and toilets. Food on the floors would be tracked back and forth between the rooms. Food would be trapped in the cracks in the floor. Flies were a constant problem as most of the windows lacked screens.

Special attention in the report was devoted to the regions where the recruits were drawn from. In the crowded population centers of the north, the climate was more harsh, leading to the hypothesis that recruits from this area would have had multiple exposures to disease and infection. The recruits sent to Hampton Roads were, for the most part, from less populated centers south of Baltimore and the Mason-Dixon Line. The Medical Corps determined it “probable” that recruits from these areas were more susceptible to scarlet fever, mumps, measles, respiratory infections, and hookworm.

Most recruits were segregated from the general population for up to twenty-one days. This isolation aided in determining the presence of infectious disease and helped to minimize its spread. In Newport, companies would number up to one hundred recruits. Berthed together, this crowding allowed for interaction and increased supervision with a limited staff who could enforced discipline. At Hampton Roads, because of the size of the barracks, recruits were split into groups of twenty-six. Their “cubby holes” were described as dungeon-like. Discipline was difficult to enforce and many windows were broken due to “skylarking.”

Discipline was also noted to be a problem among boot camp graduates awaiting further training in various schools in the Norfolk area. While Newport was more isolated and lacked the easy access to larger population centers, Norfolk was a large urban center with modes of transportation that allowed sailors to travel to other cities and communities in the South. It was, additionally, a large seaport and shipping center. All of this contributed to a large number of cases of venereal disease at Norfolk.

The next threat to the existence of the Naval Training Station came in July 1933 when the station was ordered into a “bare maintenance” status. All activities were locked with the exception of those services required to support the Naval War College. The station was left with only forty personnel to keep services running. Recruit training ceased. This reduction in staff lasted for two years with recruit training resuming midway through 1935.

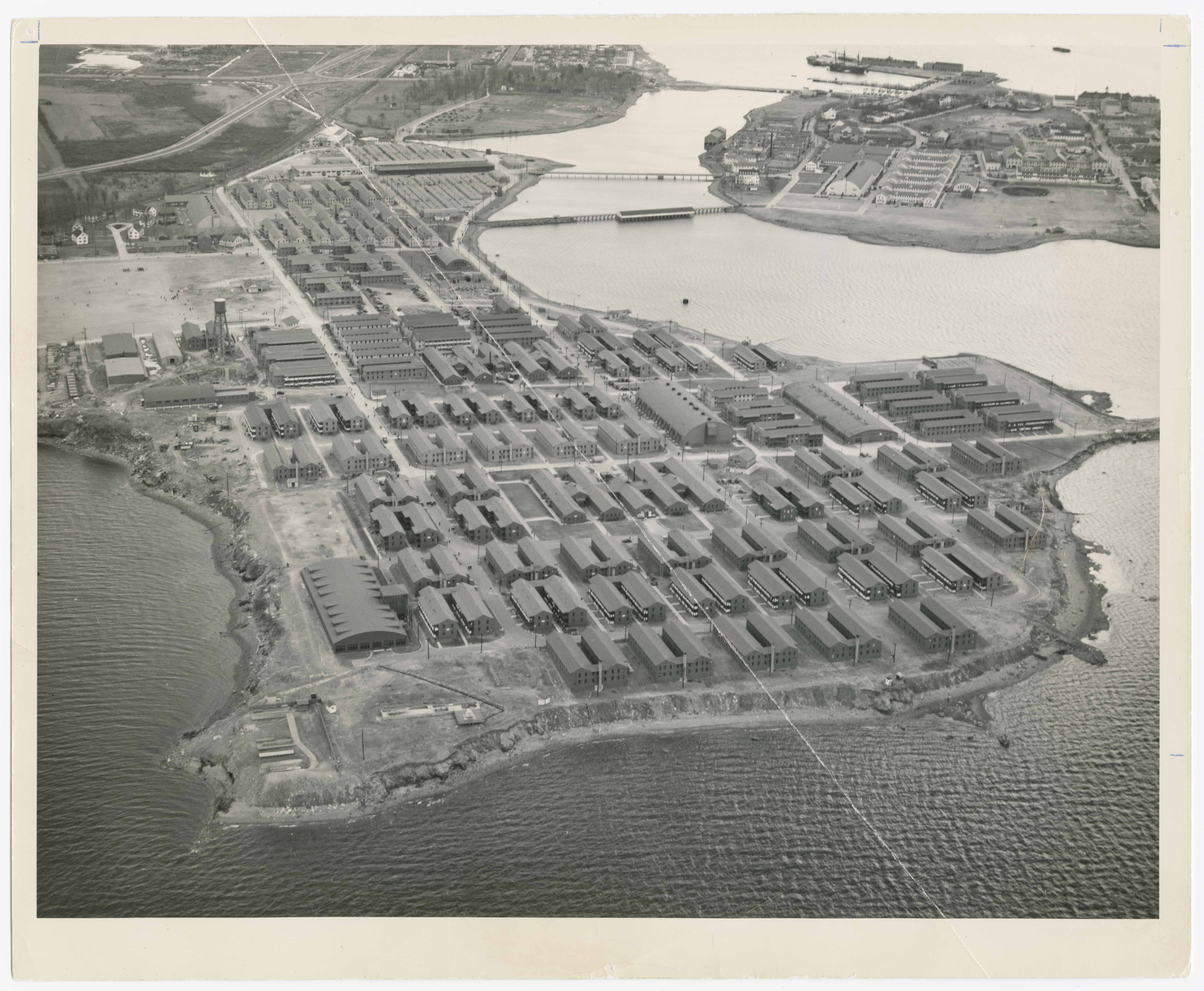

A slight increase in the recruit population occurred until 1939 when it was evident that trainees would need to be significantly increased to meet the threat of war. By 1940, the number was up to 11,648 and then, by 1941, it hit 16,000. There was a significant buildup of buildings and facilities to support the war effort beginning in 1940, marked most significantly with the expansion on Coddington Point, which was completed by the middle of 1942. Dozens of barracks and hundreds of Quonset huts for housing, instructional and administrative buildings, base fire and police buildings, medical buildings, and buildings for the new Naval Supply Depot accounted for some of the building contracts amounting to $10,000,000. Along with recruit training, the Navy established eleven different Class A and Class B schools that brought the total housing capacity on the base to 22,000 men and women.

The mission of the Naval Training Station was modified in 1943 when the recruit training mission was moved from Newport to allow for the Naval Training Station’s support of the Large Ship Pre-commissioning Training mission. By the time the last class of recruits had graduated from boot camp, there had been 204,115 recruits trained at the Training Station during World War II.

After sitting unused for many years, the war emergency camp constructed in 1917-1918 on Coddington Point was declared excess, resulting in over 200 buildings being dismantled and sold at auction (Naval War College Museum)

The Large Ship Pre-commissioning Training Program sought to bring a crew together so its members could start their training prior to the completion and commissioning of the ship. In all, an average of 85 percent of a ship’s crew would meet in Newport to start training, attending such schools as firefighting, damage control, gunnery, cargo handling, and engineering. During the Pre-Commissioning Program that ran from November 1943 until it ended on December 21, 1946, more than 300,000 sailors passed through the Training Station on their way to the newest ships in the Navy.

The large transient masses of personnel passing through Newport during the war ceased following demobilization. The Navy was faced with a reorganization more in keeping with post-war threats. Consolidation was the watchword and the Newport base began to dispose of surplus station property. The Navy razed 286 Quonset Huts and 20 wooden two-story barracks and the supporting wooden mess hall on Coddington Point and the material was later used to support the Emergency Housing Program to provide local veteran housing.

Aerial view of a portion of Coddington Point, showing more than 200 Quonset huts for housing for the Naval Training Station, September 1944. Coasters Harbor Island is in the background (Naval War College Museum)

The latter half of the 1940s was a period marked by constant changes and reorganization as the Navy sought to align the mission of the base to the needs of the fleet. A shift in officer education occurred in 1946 with the opening of the General Line School (closed in 1950). This was the first school of its kind and became a stepping stone in the educating of non-Naval Academy graduates in preparation for assignment aboard ship, greater responsibility and promotion. Although recruit training came back for a period starting in 1948, it was finally disestablished in 1952 after processing and training 25,000 recruits for the fleet during the Korean War. The mission for recruit training was transferred to other bases. The loss of this mission was countered by the opening of the Naval Academy Preparatory School (1949-1951), the Naval School of Justice, and the Fleet Training Group. The mission of the base changed to one of providing logistical support to operating forces.

The mission of the Naval Training Station has continued to change to this day. Newport has been an important part of those changes and has earned its place in U.S. Navy history.

[Banner image: Naval trainees in the Pre-Commissioning School at the Naval Training Station during World War II, probably 1944 or 1945 (Naval War College Museum)

Notes:

[1] Acts and Resolves Passed by the General Assembly of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, at the May Session, 1880. State of Rhode Island, Etc., Office of the Secretary of State, July 1880; pp 56-57. [2] Public Laws passed at the January session 1881 of the General Assembly, Chapters 37 and 839. [3] Building B would be lost to fire in 1946 and Building has been re-named Sims Hall and is presently used by the Naval War College. It is scheduled for demolition. [4] Located on the east side of Coasters Harbor Island, they were razed to make way for the Bachelor Officers Quarters in the 1960s. [5] The new fiscal year began on July 1; therefore FY22 began on July 1, 1921. The change to start the fiscal year on October 1 did not take place until 1977.