In September 1922, Isidor (“Izzy”) Einstein, then one of the most famous crime fighters in the nation and operating out of New York City, travelled to Rhode Island to go undercover to discover and arrest Rhode Island sellers of bootleg alcohol. How did this extraordinary situation come about?

The story starts on January 16, 1919, when the 18th Amendment prohibiting the sale, distribution and manufacture of alcohol with a content greater than .05% became law after the 36th state legislature ratified it. The amendment took effect exactly one year later.

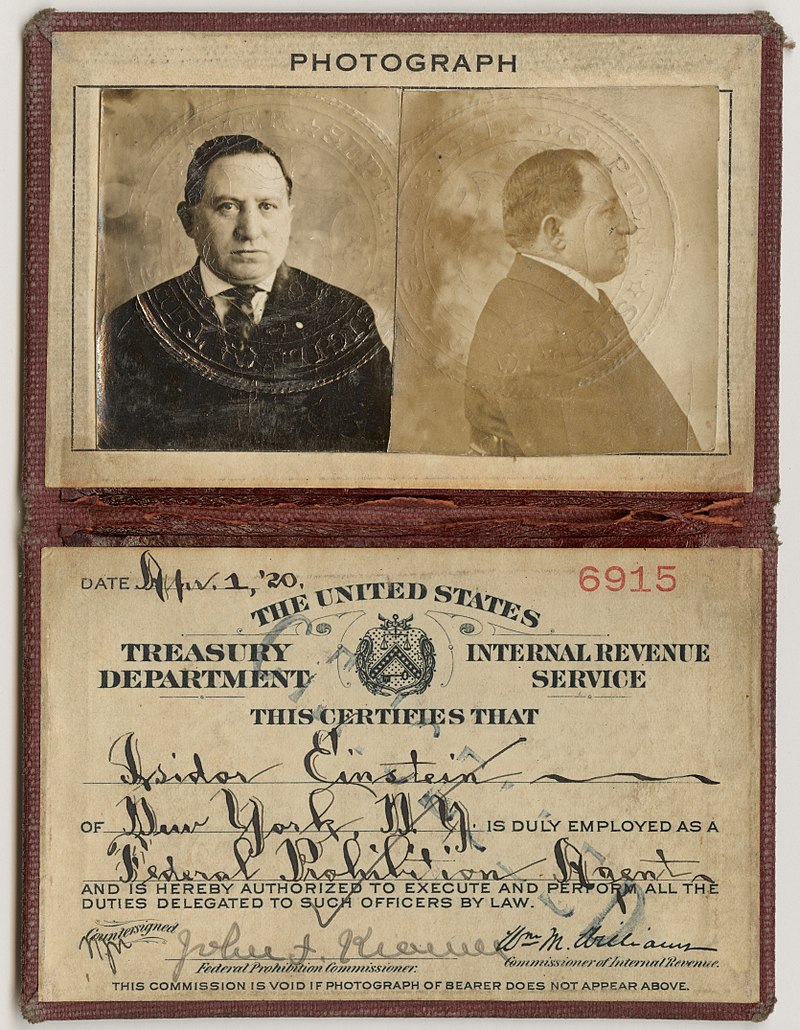

The identification card for Isidor (“Izzie”) Einstein as a Prohibition Agent, dated April 1, 1920 (National Archives)

While Rhode Island was only one of two of the then 48 states that refused to ratify the amendment (Connecticut was the other), and even though Prohibition was wildly unpopular in the state, it became the national law and applied to Rhode Island.

At the national level, Congress had to pass a federal statute to implement the 18th Amendment and provide for its enforcement. The National Prohibition Act, better known as the Volstead Act, passed in October 1919.

The enactment of the Volstead Act led to the creation of the federal Prohibition Unit (later called the Bureau of Prohibition) to enforce its provisions. It was under the Department of Treasury and made a division of the Bureau of Internal Revenue (the predecessor of the Internal Revenue Service). Roy Haynes was the bureau’s first commissioner. At the insistence of prohibition supporters, Prohibition agents who were hired had to be political appointees and not civil servants. The dry lobby expected this circumstance would give it more power in appointing senior Prohibition executives, but instead it served to create more opportunities for political cronyism and widespread corruption.[1]

From the beginning, the dry laws were flagrantly violated throughout the country. Bootleggers smuggled alcohol from Canada, stole it from government warehouses, and produced their own. Rum runners in small boats brought to the shore foreign-made liquor carried off the United States coast by supply ships from foreign countries. Saloons were replaced by illegal speakeasies, which were hidden in basements and office buildings and typically admitted only those with membership cards. With just 1,550 federal Prohibition agents initially, it was impossible to prevent huge quantities of alcohol being smuggled into the country, manufactured in local stills, and served in local speakeasies.

Rhode Island had all the hallmarks of flagrant avoidance of the prohibition law. Its population was heavily Catholic, filled with recent immigrants and second and third generation immigrant families, and was largely urban. They did not want to be dictated to by Protestant moralists, the main drivers behind Prohibition. With Narragansett Bay and its many inlets, coves and beaches, Rhode Island was ideal for rumrunners. Local fishermen helped fill out crews on rumrunners.

In the early years of prohibition, Rhode Island was one of the few states in the country not to have passed its own state enforcement law. As a result, its state and local police force was significantly hampered in enforcing the federal prohibition law. Meanwhile, just five federal Prohibition Agents from the new federal Prohibition Unit were initially assigned to Rhode Island, an absurdly small number given the hundreds of miles of state beaches, coves and other coastal lands that were ideal for landing liquor by sea. Finally, in its May 1922 session, the General Assembly passed a state enforcement law called the Sherwood Act.

Just how flagrantly Providence and surroundings areas flouted prohibition laws was demonstrated in a sensational raid by Prohibition agents on September 6, 1922. But remarkably, the federal agents were not from the Providence office. Instead, they travelled up from the Prohibition Bureau’s New York City office.

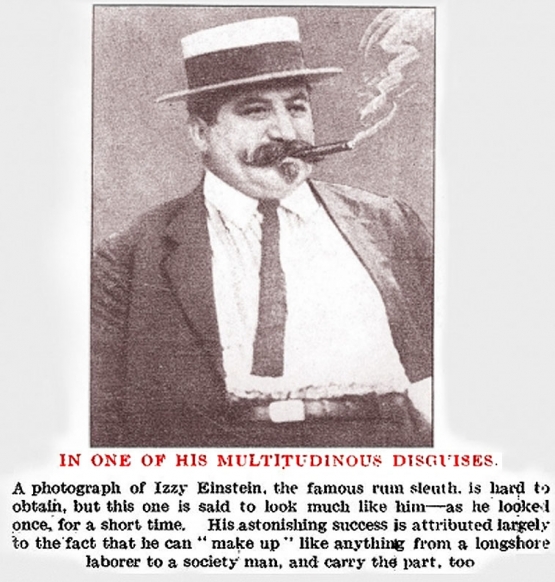

The star of the raids was the era’s most famous Prohibition agent, Izzy Einstein. At five-feet-five inches tall and weighing 225 pounds, the Jewish Austro-Hungarian immigrant had lacked any previous background in law enforcement. But he—and his sidekick Moe Smith—became masters of disguise. Examples of some of the more ridiculous personas adopted by them included Texas ranchers, opera singers, travelling violinists, an elderly Yiddish couple, beauty contest judges, pro football players (complete with uniform and helmet), and Chinese launderers. Izzy and Moe were so famous in their day that their first names were often used in newspaper headlines and most readers knew exactly who they were. The two were dedicated workers. In their spectacular five-year careers as Prohibition Agents, Izzy and Moe were said to have made more than 4,000 arrests resulting in the seizure in excess of five million bottles of liquor, most all in New York City.[2]

Izzy found Rhode Island to be a tough nut to crack, even if a number of saloonkeepers fell for his disguise as a hod carrier (a laborer employed in carrying bricks and other supplies to bricklayers and stonemasons).

Izzy brought with him Moe, Peter (“Frank”) Reager, a former boxer who once had a prize fight held in Providence, and seven other Prohibition agents from New York City. They not only worked in Providence to find illegal saloons, they were also sent on September 6 to raid five locations in Woonsocket, Pawtucket and Central Falls.

The Providence Journal, in its September 7, 1922, edition, had some amusing stories of Izzie’s antics all, no doubt, happily conveyed to the reporter by Izzie himself.

A heavy man clad in toil-soiled clothes plodded over along Westminster street in the heat of yesterday’s afternoon sun. His grimy, khaki shirt was soaked with sweat and a safety pin served the double purpose of top button and necktie. His trousers were old and their seat gave evidence of having been attacked by a sound-toothed bulldog and mended by a longshoreman whose wife had left him.

Near Franklin street, the man halted. He gazed upward at the burning sun and drew a red bandanna handkerchief from his pocket to mop his face and neck. All the while he grumbled to himself. His discomfort was so apparent that two other men who passed him that way stopped to sympathize with him.

“Hod carrying is good pay, but it’s hot,” explained the heavy man. “So hot,” he continued, “that I’ll buy a drink.”

With that the trio headed for the place at No. 615 Westminster street.

“Sixty times today have I lugged a handful of bricks up three flights,” explained the heavy man to the individual at that address, “and I and my friends need a drink.”

“What’ll you have?” inquired the host.

“Whiskey,” said the heavy man, wiping his forehead.

“Whiskey,” said his two companions, wiping their foreheads.

“Seventy-five cents,” urged the host, as he poured.

“Apiece?” asked the hod carrier.

“All together,” explained the host.

As the host turned away to make change the heavy man did a most ridiculous thing. He poured the drink, not into his throat, but into the breast pocket of his shirt.”

“That’s awful hooch,” he complained a moment later.

“Say,” he confided to his host. “Want to see something good?”

He reached into a trousers pocket and pulled out a shiny shield with his sweat-streaked hand. “Prohibition agent’s badge,” he explained. His host began to perspire.

“My name,” said the heavy man gently, “is Einstein. Izzy Einstein. Maybe you’ve heard of me?” he inquired, hopefully.

“And this,” he continued, turning to one of his companions, “is my side kick, Moe Smith.”

“And this,” turning to his third man, “is Frankie Reager. You know him. He boxed Young Montreal here eight years ago. He’s only a kid, but . . . .”

But the host’s right hand was not extended to greet the strangers. Instead, he curled up on the floor in a dead faint. It took pretty near a whole bottle of his own seltzer to bring him to, and after he had revived his visitors served him with a summons to see the United States Commissioner tomorrow morning and answer charges of maintaining a nuisance and keeping and selling intoxicating liquor. After he had been revived the man said his name was Joseph Woodcock and that he was the proprietor of the place.[3]

In all, some thirty proprietors and bartenders received summonses. The Prohibition agents only worked from 12 noon to 8 p.m. Other locations raided in Providence included 14 West Exchange Street, 575 Westminster Street, 90 Plainfield Street, and 344 Weybosset Street (where men were selling liquor on the street). The most expensive hooch, at 60 cents a drink, was at the Mahogany Palace, 97 Eddy Street. Outside Providence, the following places were raided: 13 Dexter Street and 14 Dexter Street in Pawtucket, 162-164 Washington Street in Central Falls, and 102 Willow Street and 208 Arnold Street in Woonsocket.[4]

At the Dresden Café at 121 Snow Street in Providence, the bartender, James Whalen, attempted to destroy all the bottles of liquor and resisted arrest. A brawl ensued, with former boxer Peter Reager in the middle of it.[5]

Izzy later said of the illicit liquor in Providence, “its rotten stuff most of it, but it’s easier to get here than it is in New York.”

The Providence Journal added that the raiders had dressed in various disguises, including as hod-carriers, bricklayers, fruit peddlers, street corner bums who had found a dollar, and even as plain citizens.

The Providence Journal had more amusing tales to tell, including the following:

At 529 Atwell’s Avenue, Izzy, Smith and Reager, who were then in the vegetable peddling business, found the door locked. After cursing their luck volubly in front of the place, the door was finally opened, but the thirsty trio was denied admittance. The ensuing conversation, as reported later, ran about as follows:

“Give me a drink.”

“Nobody comes in here unless we know ‘em.”

“You know me. I been peddling on the Hill for three years.”

“Come in.”

Here, according to Einstein, the agents were served with whiskey at 50 cents a glass, poured from a bottle containing a “Ginger Ale” label and top cap.

“I keep the door locked, because you can’t tell prohibition men are coming,” their host explained.

“Good plan,” said Izzy, as he filled out a summons. The man gave his name as Samuel Wax.[6]

The New York Times, in its September 11, 1922, edition, quoted Izzy Einstein extensively regarding the flagrant violation of the Prohibition law in Rhode Island:

According to Izzy Einstein, the most active and persistent raider of the prohibition land forces, the dry law is being more flagrantly violated in in Providence, R.I., than it ever was here [in New York City]. Einstein and a squad of nine other agents, including Moe Smith, was sent to wage a war on the rum traffic in the Rhode Island capital. Einstein and Smith came back to New York for the weekend, and after appearing as witnesses in the Federal Court here today, will return to Providence tonight.

“The town is wide open, or rather was, when we arrived last week,” said Einstein last night. “We made a total of about fifty arrests, but there are no fewer than 700 more places openly selling whiskey. Providence is worse than New York ever was in its disregard for the prohibition law. Liquor is sold openly in all parts of the city, in the most fashionable places as well as in the cheap dives on the waterfront. Several of the saloonkeepers deliberately disregarded the summonses which were served on them to appear before the United States Commissioner. This is something that has never happened in New York.

“All the defendants arrested or served with summonses said they had never been molested before, and I guess that is true. Every one of them put up a battle with the agents. In one place the saloonkeeper threw a pitcher of whiskey in my face. The so-called whiskey is being sold in Providence at 20 cents a drink, the [cheap] price alone indicating the character of the mixture.”[7]

As usual with Rhode Island, matters got lots more complicated. The raids were not the end of the story.

Federal officials in the state thought that the federal government would seek court orders to close at least one hundred drinking establishments in Rhode Island. Under the Volstead Act, places declared a nuisance could be closed for more than one year.[8] But no such action was taken.

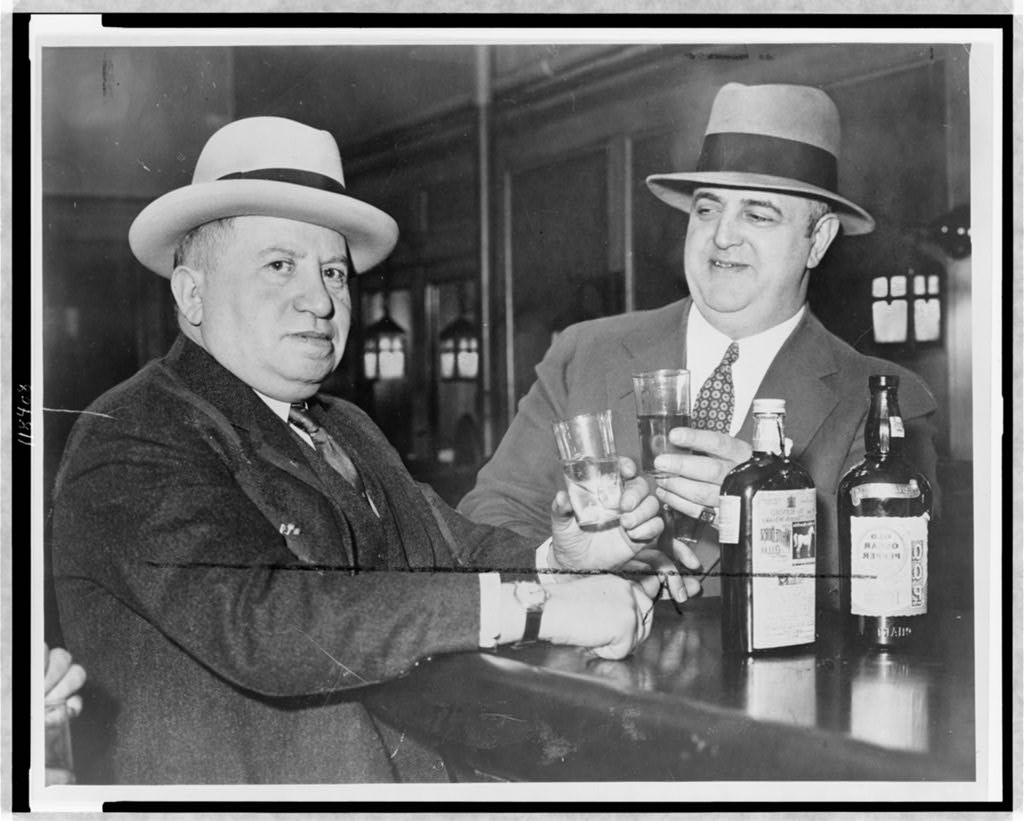

Izzy Einstein and Moe Smith take a drink at a New York City Bar in 1935, two years after the repeal of Prohibition and ten years after their termination as Prohibition agents (Library of Congress)

The New York Herald wrote of the raids in Rhode Island:

The chief interest in the liquor question revolves around a feud between two bands of bootleggers. There is a local “enforcement” law, so-called, but it is not particularly oppressive. The federal Prohibition Bureau admits that Rhode Island is a hard sponge to squeeze. Commissioner [Roy] Haynes came here the other day and fired everybody connected with his department “for the good of the service.”[9]

The Providence Police Department, rather than support Izzy’s antics at enforcing the law, became angered. Police officers objected to Izzy’s description of the lawlessness at the city’s saloons, since it highlighted their own unwillingness to enforce the state’s prohibition law. Police commissioners claimed that they had made some 400 arrests of saloon proprietors and bartenders, including at all the places visited by the Prohibition agents. Police officers criticized Izzy as a comic actor and a “four flusher” (meaning a cheap skate trying to get publicity).[10] But at least the police officers were not fired, unlike the entire Providence office of the Prohibition Bureau.

Finally, Izzy and Moe, as well as the former boxer Peter Reager, were arrested by bold local deputy sheriffs in Rhode Island, because of lawsuits filed by some of the arrested men. James C. Taylor of Central Falls, a proprietor who had received a summons, filed a suit alleging he had been assaulted. Two suits of $5,000 each were filed against Reager by David W. Collins of Pawtucket, one for assault and the other for trespass (the inexperienced Reager broke open the doors of Collins’s establishment). Einstein was freed on bail of $10,000, provided by a Providence coal merchant. In Washington, D.C., Commissioner Roy Haynes dispatched a team of lawyers and agents to defend his men.[11] The main attorney representing the plaintiffs, Daniel Hagen of Providence, would go on to represent numerous Rhode Islanders later charged with bootlegging or rumrunning.

Reager resisted arrest and found himself in more trouble. Before resisting, Deputy Sheriff Herman Pastor informed him, “If you will not go in peace, you will go in pieces.” The great Providence Journal journalist Garrett Byrnes wrote, “Even Izzy couldn’t have topped that line.”[12]

Annoying Izzy, Moe, Reader and other Prohibition agents may have worked, even if most of the suits failed. The Prohibition Bureau did not send any more out-of-state agents to Rhode Island, despite Izzy stating that New York City in its wildest night was never so belligerently law-defying as Providence.

Charges against Samuel Wax, who foolishly allowed Einstein and his cohorts into his establishment at 529 Atwell’s Avenue, were dropped on a technicality.[13]

Izzy Einstein and Moe Smith were fired from their positions as Prohibition agents in November 1925. The ostensible reason for their firing was that their identities were too widely known.[14] This was an odd rationale, given that Izzy and Moe specialized in disguises.

Notes:

[1] Michael A. Lerner, Dry Manhattan: Prohibition in New York City (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007), 46. [2] See Karl Smallwood, “Izzy Einstein, the Littlest Prohibition Agent,” online article at http://www.todayifoundout.com/index.php/2016/03/izzy-einstein-littlest-prohibition-agent/; “Izzy and Moe End Careers as Dry Agents,” New York Times, November 25, 1925; “Izzy and Moe: Their Act Was Good One Before It Flopped,” Boston Globe, November 22, 1925. [3] “Izzy Einstein, N. Y. Dry Agent, Conducts Whirlwind Raids Here,” Providence Journal, Sept. 7, 1922, pp. 1-2. [4] Ibid. [5] “U.S. Sends Experts to Aid ‘Drys’ Here,” Providence Journal, Sept. 10, 1922, p.1 [6] “Izzy Einstein, N. Y. Dry Agent, Conducts Whirlwind Raids Here,” Providence Journal, Sept. 7, 1922, pp. 1-2. [7] “Izzy Einstein Found Providence Wide Open, More than 700 Places, He Says, Where Whiskey Can” be Bought, Some at 20 Cents,” New York Times, Sept. 11, 1922, p. 19. [8] “Sheldon to Close Saloons Here As ‘Common Nuisance,’” Providence Journal, September 8, 1922, p. 8. [9] “Rhode Island Fight to Have Cash Basis,” New York Herald, Sept. 12, 1922, p. 4. [10] “Providence Police Denounce Einstein,” Providence Journal, Sept. 12, 1922, p. 2; “Providence Police Denounce Einstein,” Fall River Globe (Fall River, Massachusetts), Sept. 12, 1922. [11 “Izzy Einstein and Two Federal ‘Dry’ Agents Arrested,” Providence Journal, September 9, 1922, p. 1.; “U.S. Sends Experts to Aid ‘Drys’ Here,” Providence Journal, Sept. 10, 1922, p.1. [12] Garrett D. Byrnes, “When Izzy and Moe Played Rhode Island, They Made a Hit at Every Engagement,” Providence Journal (Sunday edition), Sept. 3, 9172, p. 151. [13] “Einstein, Reager and Smith Here to Testify,” Providence Journal, January 1, 1923, p. 4. [14] “Izzy and Moe End Careers as Dry Agents,” New York Times, November 25, 1925; “Izzy and Moe: Their Act Was Good One Before It Flopped,” Boston Globe, November 22, 1925.