In the run up to the 250th anniversary of the American Revolution, we will hear much about the Founding Fathers. Portsmouth, Rhode Island, however, was the first American community that could boast of a Founding Mother. That female foundress was the irrepressible Anne Hutchinson.

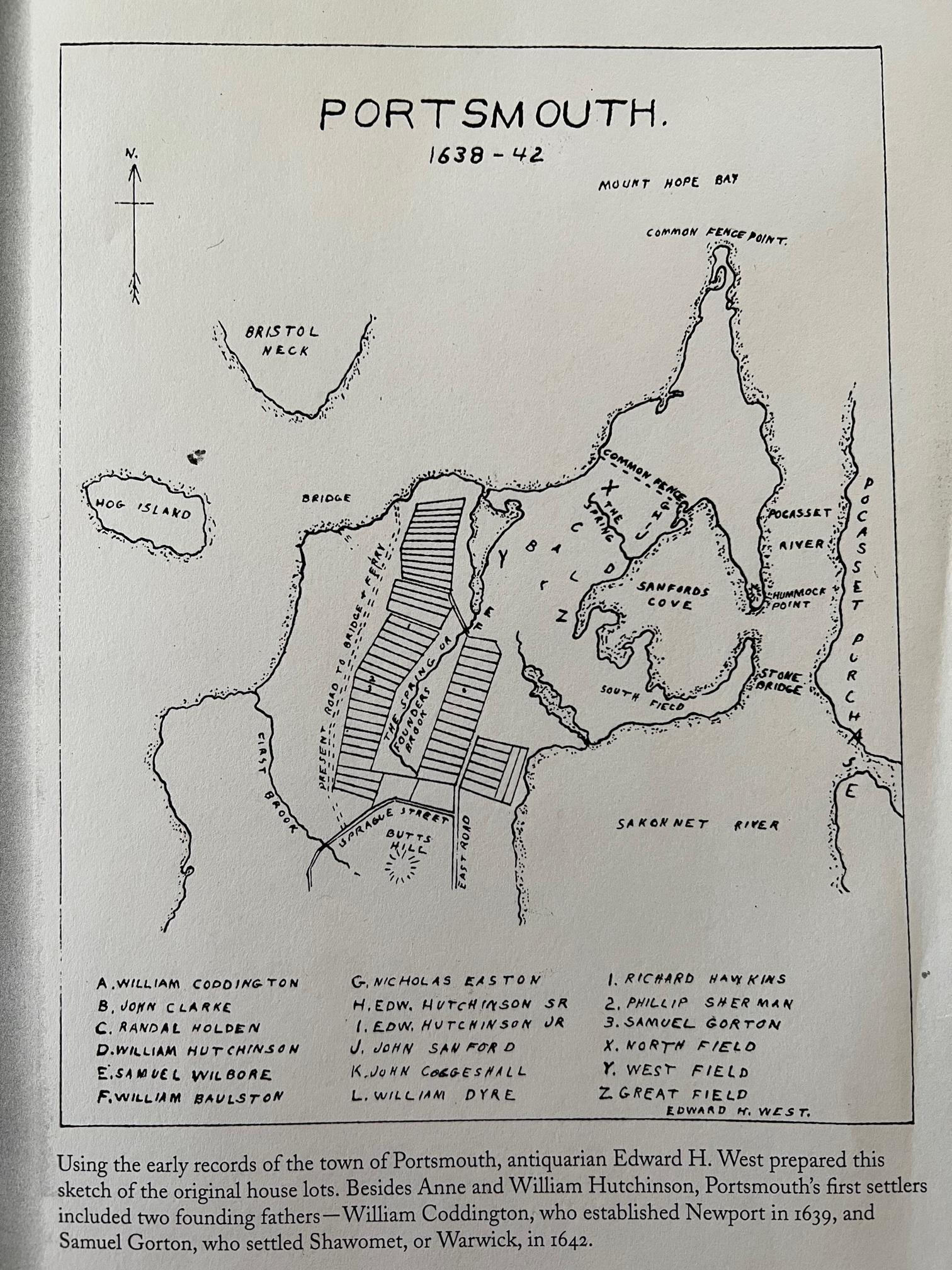

True, William Coddington, a prominent merchant of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, purchased all of Aquidneck Island in 1638 from the Narragansett Indians (who had seized it from the Wampanoags) through the intercession of fellow exile Roger Williams. But Coddington was acting on behalf of a group of religious dissenters known as Antinomians, the most controversial of whom was Mistress Anne Hutchinson.

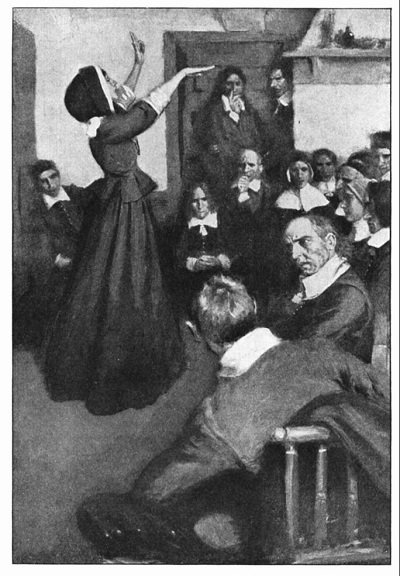

Illustration of Anne Hutchinson preaching in her house in Massachusetts. No contemporary drawing of her exists (Harper’s Monthly, Feb. 1901)

Who was this remarkable Rhode Island pioneer, variously called by historians “a charismatic healer, with the gift of fluent and inspired speech,” “another Joan of Arc,” a woman whose “stern and masculine mind … triumphed over the tender affections of a wife and mother,” and “the troubler of the Puritan Zion”? Her archenemy, Governor John Winthrop of Massachusetts Bay, offered a contemporary estimate: he called her the American Jezebel, an allusion to an Old Testament Phoenician queen legendary for her alleged wickedness.

Anne was born in Lincolnshire, England, in 1591, the daughter of an English clergyman named Francis Marbury, who was censured by the Anglican Church for his Puritan leanings (the Puritans wanted to purify the Church of England from any vestiges of the rejected Roman Catholic religion). In August 1612 the well-bred and educated Anne married William Hutchinson, the son of a prosperous merchant. They both became committed Puritans. During the next twenty-two years she dutifully bore her husband fourteen children. Then, in 1634, with the Puritans in disfavor because of the High Church leanings of King Charles I, the Hutchinson family set sail for Boston.

Anne’s early religious training, her vigorous intellect, and her restless and inquiring mind led her to take a leading part in the theological life of her intensely religious community. At first she held informal meetings of women at her home, and on these occasions she would discuss the lengthy sermons of the previous Sunday. This activity was unobjectionable. Gradually, however, she began to lecture to mixed audiences of sixty to eighty listeners and to expound her own religious beliefs and provide commentary on recent sermons by male ministers. This practice caused a furor.

Mrs. Hutchinson and the Reverends John Cotton and John Wheelwright preached a new doctrine that they termed “a covenant of grace.” This view, held by a small minority of Puritans, asserted that salvation came principally through the individual’s own personal awareness of God’s divine grace and love. It challenged the orthodox “covenant of works,” which was embraced by established, formal churches whose members gave evidence of their predestined salvation by their works and their status in the community.

Hutchinson and her associates denied that Christian freedom should be restricted by a need to seek evidence of election or salvation in obedience to God’s law as interpreted by “hypocritical ministers.” Since they placed their own intuitive interpretation of God’s law above the civil and religious laws devised by man, those who believed in the covenant of grace were derisively labeled Antinomians, a word that comes from the Greek anti (against) and nomos (law).

It has been said of seventeenth-century religion that the Anglicans discarded the pope; the Puritans (later becoming Congregationalists) then discarded the bishops in favor of a formal, theologically trained clergy; but the Baptists were content with an ad hoc, inspirational ministry to spread the word of God.

Hutchinson’s view, emphasizing the direct connection between man (or woman) and God, undermined the authority and importance of the established religious and civil leaders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony (who contended that society ought to be governed by Christian magistrates), because she discounted the need for a specially designated and highly educated ministry. In fact, the Antinomians (and their theological successors, the Quakers) dispensed with the clergy altogether and stressed the indwelling of the Holy Spirit and direct relations with God without the need for human intermediaries.

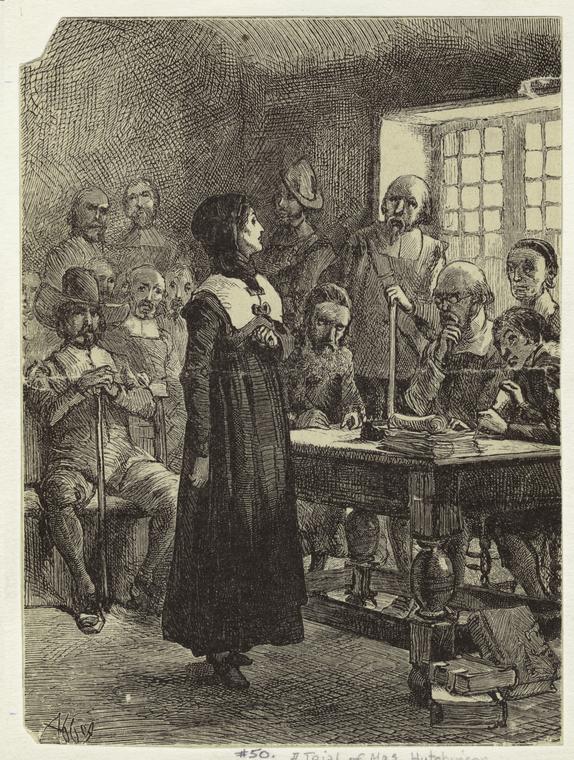

Such dogmas as Antinomianism and Quakerism shook the Bible Commonwealth of Massachusetts to its foundations. When advanced by a female (some labeled Anne a witch), they were even more pernicious. Anne was put on trial on November 7, 1637 on the charge of slandering ministers. She defended herself with impressive intelligence and passion. Nevertheless, led by John Winthrop, the court was found to be a heretic and condemned “as being a woman not fit for our society.” Anne suffered excommunication and banishment for her beliefs, so she, her husband, and numerous followers, including William Coddington, sought refuge in the Narragansett Bay region—an area that Puritans dubbed New England’s “moral sewer.”

Anne Hutchinson at trial in Massachusetts Bay. Edwin Abbey Austin, artist, circa. 1876-1881 (New York Public Library Digital Collections)

Soon after her arrival at Portsmouth in the spring of 1638, she clashed with her coreligionist William Coddington, who held Indian title to Aquidneck Island in his own name. Joining with the equally rebellious Samuel Gorton, who later founded Warwick, she ousted Coddington from power, so he went to the southern tip of the island and established the town of Newport in 1639.

Although bested temporarily, the very ambitious Coddington was not beaten, for within a year he had cleverly engineered a consolidation of the two island towns under a common administration in which he was “governor.” Gorton and at least eleven other Portsmouth settlers responded to Coddington’s resumption of power by plotting armed rebellion against him. These Portsmouth dissidents were ultimately banished from the island. Anne soon broke with the Gortonists over the use of violence, and she and her husband joined the Newport settlement.

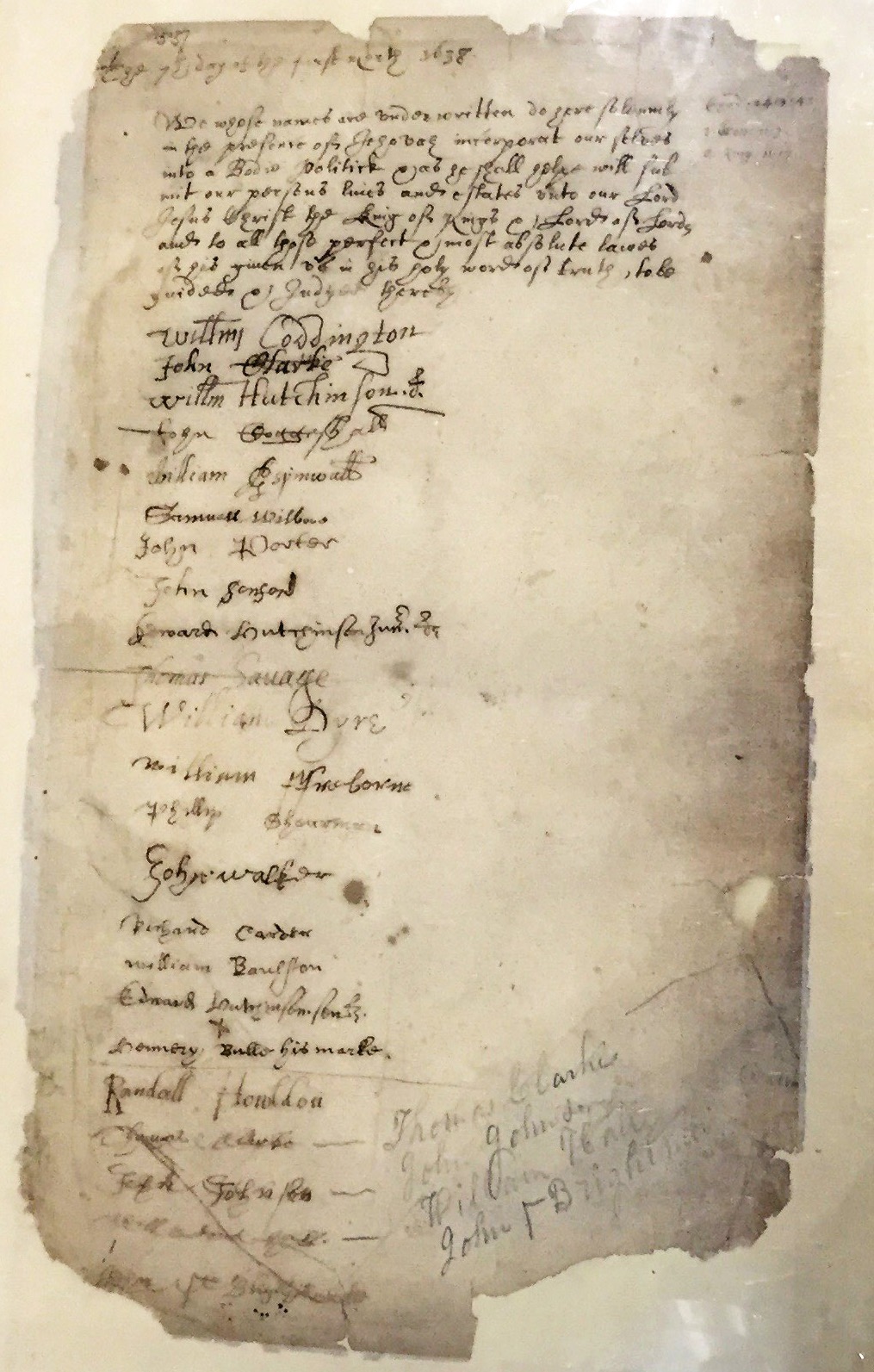

According to the Portsmouth History Center: “The Portsmouth Compact was a document signed on March 7, 1638 that laid the foundation for the establishment of the town of Portsmouth on Aquidneck Island later that spring. It was the first document in history that severed both political and religious ties with mother England.” (Rhode Island State Archives)

Shortly thereafter, Anne’s fortunes plummeted disastrously. William Hutchinson died, her religious leadership waned, and her nemesis Massachusetts threatened to absorb the Rhode Island settlements.

Disgruntled and disillusioned, Anne sought refuge in the Dutch colony of New Netherlands in 1642. In the late summer of 1643 her home (near present-day Pelham Bay, New York) was in the middle of a war between aggressive Dutchmen from New York City and the Indians they wanted to evict. Anne perhaps thought she was protected due to her former good relations with the Narragansetts. But her house was raided by members of the Siwanoy Indian tribe, who killed Anne, two of her sons, and three of her daughters in brutal fashion.

The Massachusetts clergy rejoiced over the grisly murders. The Reverend Peter Bulkeley spoke for most orthodox Puritans when he pronounced this eulogy: “Let her damned heresies … and the just vengeance of God, by which she perished, terrify all her seduced followers from having anymore to do with her heaven.” The Bay Colony divines considered Anne Hutchinson’s death to be the symbolic death of Antinomianism, but the new religion of the Quakers found many recruits among Anne’s followers—William Coddington, her political rival, being the most notable.

Portsmouth’s foundress was a remarkable individual. The double oppression of life in a male-dominated society and biological bondage to her own amazing fertility was an impediment to leadership that she successfully overcame. After Anne’s arrival in Portsmouth and throughout the remainder of the century, women publicly taught and preached throughout Rhode Island; in part because of her example, the men of the colony protected the liberty of women to teach, preach, and attend religious services of their own choosing. It would not be boosterism or hyperbole to call Mistress Anne America’s first great female leader. An indomitable mind, a zeal for equality, and an energy that kept her constantly in motion indicate that this seventeenth-century prophetess was the archetype of the late-twentieth-century woman.

Massachusetts has recanted. Admitting its unjust treatment of Mrs. Hutchinson, it commissioned the famous sculptor Cyrus E. Dallin to fashion a statue of her, enfolding a child within her robes. Dedicated in 1922, that artwork, which bears an inscription calling her a “courageous exponent of civil liberty and religious toleration,” now occupies a hallowed niche in the Massachusetts Statehouse for passersby to view and ponder.

If the town that banished Anne Hutchinson can be so lavish in its praise, is it not time for Portsmouth, the town established as a result of the endeavors of this legendary American, to accord its Founding Mother a similar memorial? (In 2013, the 375th anniversary of Portsmouth’s founding, Founders’ Brook Park, off of Boyd’s Lane in Portsmouth, was dedicated. It has an Anne Hutchinson Granite Bench and an Anne Hutchinson and Mary Dyer Memorial Herb Garden. While this is a good start, it is not on par with the Boston statue.)

[The original version of this essay was requested and written in 1988 to celebrate the 350th anniversary of the founding of Portsmouth, and was included in Rhode Island in Rhetoric and Reflection, Public Addresses and Essays by Patrick T. Conley (Rhode Island Publications Society, 2002)]