[Editor’s note: This article is a synopsis of the book by Varoujan Karentz, The Life Savers, Rhode Island’s Forgotten Service (Charleston, SC: CreateSpace, 2012), ISBN-13-978-1463791025, and also contains excerpts from it]

While Rhode Island’s maritime history reaches back before the colonial period, the era following the Civil War between 1872 and 1938 had boosted Rhode Island’s maritime traffic to substantial numbers to match the need of its industrial growth. Shipping exceeded all other modes of transportation by orders of magnitude. The number of ships, cargo and passenger’s transiting the waters of Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island Sound and Block Island Sound escalated each year. During the year 1893 more than 60,000 vessels passed Point Judith and over half of these (34,000) were coastal schooners. Even later, in 1917 when rail transportation of freight and passengers had become prominent, some 70 to 100 vessels passed by Point Judith each day. Within Narragansett Bay, Lighthouse Keeper logbooks of “Passing Vessels” at Beavertail Light Station recorded over 15,000 vessels per year. Another stream of vessels outside the Point Judith venue transited east and west of Block Island bound for more distant venues, adding thousands more to the count. This was also the peak period of coal usage and hundreds of towed coal barges transited Rhode Island’s coastlines and Narragansett Bay. Many of these barges were converted from large multi-masted vessels and were no longer seaworthy under sail.

Along with this unprecedented growth came shipping collisions, groundings, and debilitating storms resulting in loss of vessels, cargo and lives. Sailing vessels were cumbersome in strong winds and tides and early steam vessels underpowered. Navigation aids were few and unreliable, coupled with rare or non-existent weather forecasts. Winter storms added additional risks with poor visibility and frozen rigging adding hazardous conditions for both crew and passengers.

During the period from 1875 to 1904 the number of lives lost to shipwrecks along U.S. shores averaged from 250 to 350 per year. Between 1903 and 1904, a total of 1,281 lives were lost.

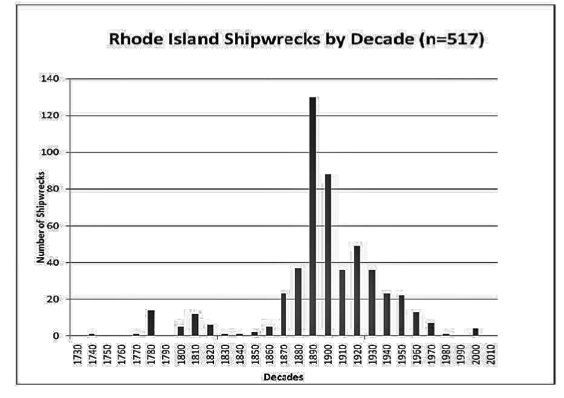

From the early 17th century through the colonial period, shipwrecks were not uncommon in Rhode Island’s waters. Three hundred fifty miles of coastline consisting of rocks and sandy beaches, coupled with uncharted underwater hazards, currents and unreliable or nonexistent navigation aids, contributed to a vast accumulation of shipwrecks along and off its shores.

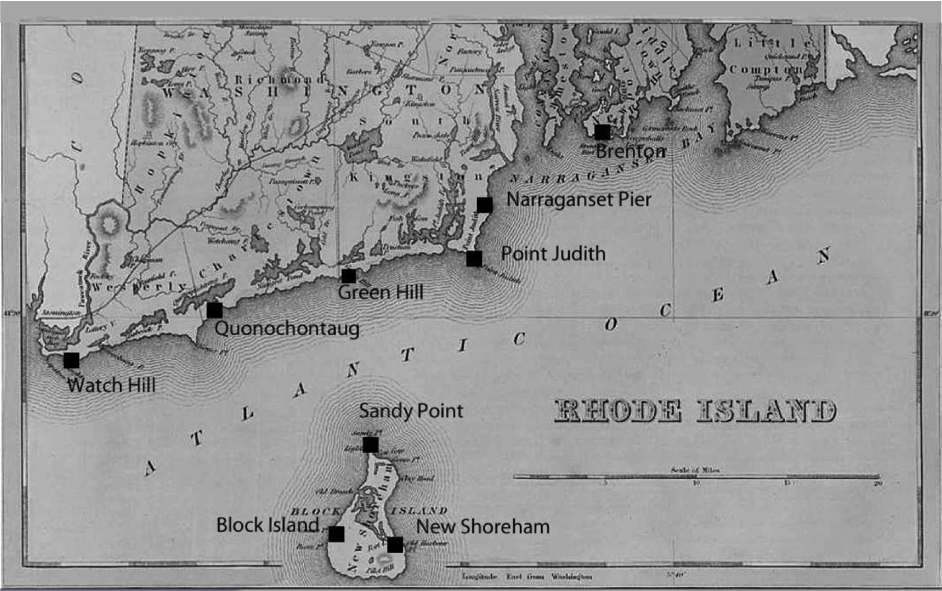

Shipwreck distribution in Rhode Island waters from 1730 to 2010 (RI Ocean Special Area Management Plan July 23, 2010)

More recently, the Beavertail Lighthouse Museum Association’s Rhode Island maritime event data base (http://beavertaillight.org/wrecks/index.html ) has grown to over 2,600 documented events, many being shipwrecks.

The largest percentage of shipwrecks occurred along the state’s southernmost shore that fronts the Atlantic Ocean. Rhode Island and Block Island Sounds define this region. The area is mostly a flat moraine of barrier beaches with scattered reefs and rocks. Estimates from the period of 1650 to present day of lost cargo and life over those years has not been calculated, since there are no complete records for strandings (vessels that grounded along the shore) or events where there were not losses of vessels.

An early effort in Rhode Island to help the offshore mariner was the establishment of seaward looking lighthouses: Beavertail Light in 1749, Watch Hill Light in 1808, Point Judith Light in 1809 and Block Island Light (Sandy Point) in 1829. As coastal shipping comprised of sailing packets and schooners moved more and more cargo, passenger vessels also began populating the seaways. It was after the first passenger steamboat named the Ugly appeared on Narragansett Bay in 1817 that the clamor for more navigation aids resulted in the establishment of twenty-five additional lighthouses, plus two lightships locations. These efforts to prevent loss of lives from ship disasters set into motion additional services as national laws were enacted.

As a result, in 1848 the federal government established the “U.S. Life Saving Service.” The service consisted of manned stations linked as a chain of coastal seaward sentinels established for one purpose—to save lives. Today, life-saving at sea brings to mind Coast Guard cutters and helicopters. What preceded them was a heroic service of hearty men and hundreds of life-saving stations, which eventually was folded into the U.S. Coast Guard service. (It was not until 1915 that the U.S. Revenue Service and the U.S. Life Saving Service were combined and became the U.S. Coast Guard.)

Organizationally, the Life Savers were a sequence of overlooks along the nation’s coastline with men walking the beaches and looking for ships in distress or stranded perilously on rocks and shoals. This string of guardians stretched over parts of the Eastern Seaboard, Gulf of Mexico, Great Lakes, and western shores including Alaska. Eventually 279 stations were built and manned by 1,898 “surfmen.”

The surfmen’s motto, “You have to go out, but you don’t have to come back” was instilled in each crew member. They started out as volunteers and were gradually recruited into government service. The stations grew with America’s commitment to saving the lives of those involved in marine disasters. As part of a nation-wide establishment of coastal stations, their duties (with very few exceptions) would take place when the sea and surf was in turmoil with treacherous waves and white water pulsed by screeching gale force winds. Few know of their remarkable feats of heroism.

For over sixty years, men from nine Rhode Island U.S. Life Saving Stations monitored the southern Rhode Island coastline and Block Island. Six were located fifteen miles apart along Rhode Island’s south shore from Newport to Watch Hill, while three were on Block Island.

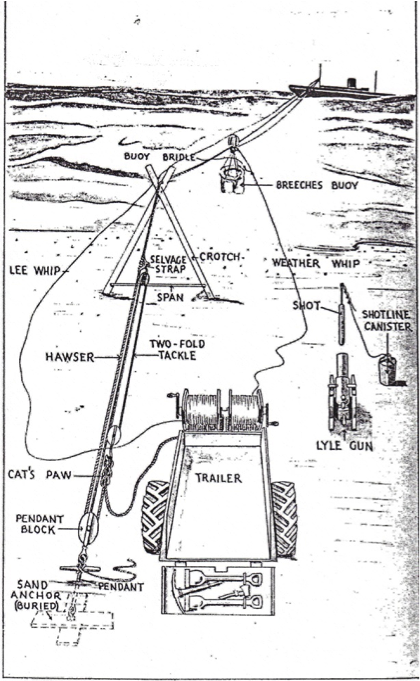

Each was manned by a crew of six “Surfmen” and a “Keeper” who performed beach patrol between stations and upon sighting a wreck or an impending foundering or stranding of a vessel, fired a recognition/warning “Coston Signal” flare. The surfman then alerted station crew members who then launched, as needed, their rescue surfboat or breeches buoy apparatus.

At each station, crew members lived together, taking two-man shifts each night walking in opposite directions from their station along the beach until they met a surfman from an adjacent station. Some exchanged tokens as proof of completing their patrols.

Beach apparatus weighing 1,700 pounds was packed on to a cart, stored at the station and typically hauled to the rescue site over dunes, crevasses, marsh grass, rocky beaches and foot paths. The difficulty of the labor added greatly to limiting a surfman’s physical endurance for the actual rescue operations. Setting up equipment required extra effort in raising voices to be heard over the howling wind and pounding surf.

Here are the locations of Rhode Island’s nine United States Life Saving stations, when they were established, and in parentheses a short statement of what happened to them. (An SAR is a United States Coast Guard search and rescue unit).

Block Island

Block Island Station, 1872 (active SAR during summer months supported by Point Judith; relocated to Salt Pond; original building now a private residence)

New Shoreham Station, 1874 (building relocated to Mystic Seaport Museum in 1968)

Sandy Point Station, 1898

Block Island Sound and Rhode Island Sound

Watch Hill Station, 1879

Quonochontaug Station, 1891

Green Hill Station, 1912

Point Judith Station, 1876 (active SAR)

Narragansett Bay

Narragansett Pier Station, 1872 (building exists today as the Coast Guard House Restaurant on Ocean Road in Narragansett)

Brenton Point Station, 1884 (active SAR relocated in 1939 to Station Castle Hill)

Dramatic events culled from unadorned documented reports describe feats of a forgotten service that saved lives. Each year the stations were required to submit reports of the station’s activities. Organized by districts, the annual reports describe not only the rescues and attempts by each station, but also include the service’s annual development of new rescue apparatus and improvements in procedures.

Each maritime event in itself is a story of drama, hardship and astonishment almost always experienced in harsh weather. Stories include the successful use of the breeches buoy where passengers or crew were hauled ashore directly from stranded vessels. They include stories of launching surfboats in horrendous seas and gale force winds. Frostbite and exhaustion were common, as was the fear of the sea. The deaths of crew members or passengers added tension to the attempted rescue. However, emotions and heroics are subdued in the written testimonies and must be imagined by the reader.

Steamship Spartan before breaking up on Block Island, March 1905. After seventeen men on board were saved by surfboat, the four remaining crewmen, one by one, are being rescued by breeches buoy (U.S.C.G.)

Rhode Island’s most significant marine disaster, a collision between the 128-foot three-masted schooner Harry P. Knowlton and the Joy Line’s 252-foot long passenger steamer the Larchmont, took place on the night of February 11, 1907. The collision occurred on open waters outside of sight and sound of the any of the Life Saving stations. The Larchmont, a steam-powered side paddle wheeler on route from Providence to New York, was holed off Watch Hill by the sailing schooner laden with 500 tons of coal. The Knowlton mistook the steamer’s course and drove its bow into the port side of the steamer. The air temperature was -3° Fahrenheit and breaking seas and wind-driven spray froze to everything that was above water.

Larchmont sank within minutes of the collision. Neither vessel burned signals that could have been seen from shore. In the aftermath, hours later, a massive operation to rescue survivors and search for victims both dead and alive was set into motion.

The “call to arms” collected rescue vessels from nearby the collision area and from afar. The Harry Knowlton, with its crew unaware of the damage its ship caused to the Larchmont, began to fill with water until she reached a point off Quonochontaug. Her crew put out in the schooner’s lifeboat and rowed ashore. The strong northwest wind carried the remains of the Larchmont, her few survivors and the dead passengers and crew, the bodies frozen stiff, back toward Quonochontaug, Point Judith and Block Island.

While Rhode Island’s Life Saving Stations played no part in preventing the disastrous collision, they responded to save the few that made it to shore by providing clothing, food and shelter. The grimmer task was collecting the frozen victims who washed up on the beaches.

Two days after the disaster, it was reported that 138 lives aboard the Larchmont were lost and only 17 survived. The actual count was never confirmed. Some death estimates were as high as 150 passengers and another 50 crewmembers. Some survivors came ashore on wreckage, others in boats, and one intrepid young man actually swam ashore. Frozen bodies, some with only nightgowns on and covered with ice and layers of salt spray, were recovered from ocean waters and beaches.

Surfmen from Rhode Island’s Life Saving Stations responded without hesitation or concern for their own safety. The night was exceedingly cold, dark and stormy. The event occurred at 11:00 p.m., ten miles northwest of Block Island and three miles southeast of Watch Hill. The collision was too far off shore for anyone at the four Life Saving Stations along the south coast of Narragansett or the two stations on Block Island to see. The first news of the disaster came only after a single survivor by the name of Fred Hiergsell swam ashore after his lifeboat was swamped. He knocked on the window of the Block Island Lighthouse (North Light on Sandy Point); after telling his horrible tale, the lighthouse keeper called the nearby Life-Saving Station. Keeper Cat McVey aroused his crew and alerted the surfmen on the other side of the island at the New Shoreham Station. Other passengers also arrived. Some lived, but most died. Bodies began to wash up on Sandy Point, and by noon the next day forty bodies were recovered by the life-saving crew. The Life-Saving Service 1907 Annual Report stated:

Block Island’s two life-saving stations, one at Sandy Point and the other at New Shoreham, were turned into morgues and hospitals during the night, and the dead crowded the living. The boat room floors were lined with the dead, each one frozen as stiff as the boards on which they rested. In the living and sleeping rooms the suffering survivors rested on cots and beds, racked with the pain of frozen limbs and shuddering with the recollection of the horror of their experiences. Many were denied the merciful unconsciousness of sleep, and throughout the long, dreary night they tossed and cried and sobbed, and the howling wind outside only served to keep fresh in their minds the terrors of the storm through which they had fought their way to the island. It is feared that none of those survivors will remain unscathed. The frost penetrated too deeply to be overcome by medical treatment and the surgeon’s knife will be the only salvation of some of the unfortunates. Some will lose fingers, some hands, and it is feared some will be obliged to have limbs amputated.

The 1898 stranding of the three-masted British Schooner Vamoose, one of the larger vessels ever to come ashore on Block Island, exemplified the complications of rescue attempts. The stranding took place on December 5, 1898, during a strong northeast gale three miles north of Block Island’s Life Saving Station.

The Vamoose was on route from Cape Brenton Island to Saint John, New Brunswick. She encountered a series of vicious storms, including a cyclonic tempest that drove her far off course by hundreds of miles to the south. For over fifteen days she had been at the mercy of heavy seas and a succession of gales. She sought refuge in the vicinity of Long Island Sound. In poor visibility, driving westward under double-reefed sails and flying jibs, she struck hard along the Block Island beach above Clay Head with seas sweeping over her. The captain, Byron Knowlton, sought protection by moving to the top gallant forecastle, and the rest of the crew leapt into the mizzen mast’s rigging. Winds by this time were clocked at sixty miles per hour at Block Island. Within ten minutes, Captain Knowlton was washed overboard and never seen again. Shortly thereafter the mizzen topmast was carried away and the mate H. Brooks fell and disappeared into the raging surf.

As the vessel began to break up, the remaining crew attempted to make a raft. Two crew members (Webb and Christiansen) luckily made it ashore, but were thought to have drowned by the crewmen still aboard the vessel. Being half frozen to death, the two crewmen managed to climb ninety to one hundred feet to the top of Clay Head and reached the house of Mr. Samuel L. Harper. Harper dispatched his son to the New Shoreham Life Station with the news. The wreck, however, had already been discovered by the north patrol. Keeper Amazon Littlefield of the station secured a team of horses to pull both the beach cart and the surfboat four miles to the Vamoose, which was lying 120 yards offshore with the four men still aboard clinging to the mizzen rigging. Lowering the surfboat down the steep face of the bluff was accomplished, but it soon was apparent the boat could not safely be launched among the rocks and heavy surf.

The breeches buoy was then deployed and the first shot fell through fractured the deck. The second shot was successful. With great resistance due to the current, surfmen waded waist-deep into the breakers to clear the fouled line from the rocks and rig the breeches buoy. The four remaining crew aboard the Vamoose were rescued without delay. Twenty minutes after the last man was saved, the mizzenmast fell and the stern of the vessel broke away. The final testimony of the event was a letter of appreciation from the survivors to Superintendent Sumner Kimball in Washington, D.C., dated December 6, 1898:

Sir: The undersigned, survivors of the British schooner Vamoose wrecked under Clay Head Bluffs at Block Island last Sunday night, desire to testify their heartfelt gratitude to the crew of the New Shoreham Life-Saving Station, who by their brave, plucky work saved us from sure death. Our thankfulness for their work, and our appreciation of their kind of treatment at the station later on, will never be forgotten.

The reader of the Life Saving Service’s annual reports should understand that many of them are terse and lack detail or complete descriptive narrative because they were written by the surfmen onto the station log. Unfortunately, paper and ink were not supplied in quantity, nor was writing their forte. These men lacked the vivid eloquent literary skills to describe the excitement of the rescues and of the difficult conditions under which many of the events took place. It is up to the reader to visualize the enormous burdens and physical challenges these men endured, almost always in gale force wind conditions coupled with horrendous breaking surf and seas.

Dennis Noble in his book, That Others May Live, points out that many of these surfmen were perhaps “laconic” and could not express themselves in their log writings. The men were simply doing their duty and “believed in the traditional sailors’ effort to help another sailor in distress.”

Beginning in 1895, the Life-Saving Service published periodically in its annual report the following statement:

It is manifestly impossible to apportion the relative results accomplished. It is equally impossible to give even an approximate estimate of the number of lives saved by the station crews. It would be preposterous to assume that all those on board vessels suffering disaster who escape would have been lost but for the aid of the life-savers; yet the number of persons taken ashore by the lifeboats and other appliances by no means indicates the sum total saved by the Service.

In many instances where vessels are released from stranding or other perilous predicaments by the lifesaving crews, both the vessels and those on board are saved, although the people are not actually taken ashore, and frequently the vessels and crews, escaping disaster entirely, are undoubtedly saved by the warning signals of the patrolmen, while in numerous cases, either where vessels suffer actual disaster or where they are only warned from danger, no loss of life would have ensued if no aid had been rendered.

[Banner Image: Steamship Spartan before breaking up on Block Island, March 1905. After seventeen men on board were saved by surfboat, the four remaining crewmen, one by one, are being rescued by breeches buoy (U.S.C.G.)]Bibliography:

The entire series of the annual reports (1876 -1914), courtesy of “Google Books,” is available at the websites for the U.S. Life Saving Service Heritage Association (www.http://uslife-savingservice.org/) and the U.S. Coast Guard Historian Office (www.https://www.uscg.mil/history/).

Some important sources includes the Narragansett Times, Newport Mercury, and the U.S. Coast Guard Historians Office, Washington, D.C.

For a complete bibliography, refer to the author’s The Life Savers book.