This essay was published as a Providence Journal commentary on December 6, 2012 in the aftermath of the Obama-McCain presidential contest. It was prompted by continuing speculation that population stagnation in Rhode Island and growth in the South and West might deprive Rhode Island of one electoral vote. Given the most recent election in 2016 and the attention paid to the Electoral College, this essay seems relevant today as well.

Now that the dust (and the dirt) of the latest presidential race has settled, it may be instructive to look back and view Rhode Island’s crucial role in the most bizarre and problematic presidential contest of them all. No, it was not the 2000 presidential contest Bush versus Gore.

In 1876 New York’s Democratic governor Samuel J. Tilden sought to regain the presidency from the Republicans—the party that saved the Union, but whose harsh though well-intentioned Reconstruction of the South was then dividing it. The young GOP countered with Ohio Governor Rutherford B. Hayes.

Historians have written extensively about this most controversial, ethically flawed, and legally questionable election in American history in far more depth than this brief Rhode Island-oriented commentary can provide. Suffice it to say that political reformer Tilden received nearly 252,000 more votes than Hayes, but contested returns in Florida (even then), Louisiana, and South Carolina—due to intimidation of voters by Southern Democrats and ballot fraud by the still surviving Republican Reconstruction regimes—put the 19 electoral votes from those three states in doubt. In addition, there was an irregularity in Oregon involving a single vote.

After the initial tally, Tilden had the votes of 184 electors, one short of the then-required majority, while Hayes trailed with 165 (or was it 164?). An allegedly bipartisan Electoral Commission was created to determine who would receive the 20 disputed ballots. The Republicans controlled this board by a margin of 8 to 7. Not surprisingly, the commission voted 8 to 7 to validate each state’s Republican electors, giving Hayes the simple majority of 185 needed to become the 19th president of the United States. My historical analysis places Louisiana’s eight votes in the Tilden column. The most recent scholarly book on this fiasco, written by Roy Morris, Jr., is entitled Fraud of the Century: Rutherford B. Hayes, Samuel Tilden and the Stolen Election of 1876. During his one-term tenure, the Democrats derisively called the victor “Rutherfraud” Hayes.

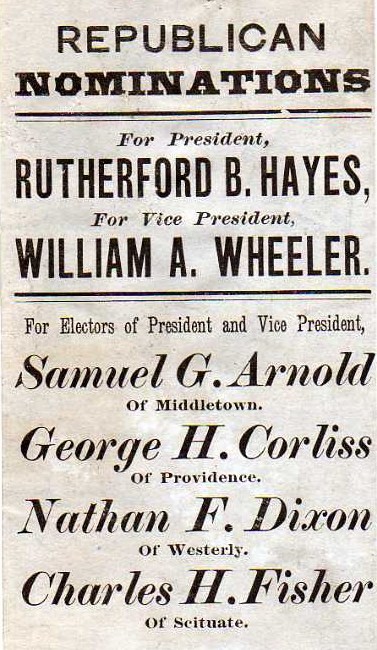

In this era, sometimes called “the Gilded Age,” Rhode Island was solidly Republican. In the general election, the state’s voters preferred Hayes over Tilden by the comfortable margin of 15,787 to 10,712, so Rhode Island’s four electoral votes appeared to be safely in the Hayes column. This appearance has caused American historians to ignore Rhode Island when dealing with the Electoral College crisis. However, one might argue that the single vote by which Hayes was elected was cast belatedly by a Rhode Island presidential elector chosen by the Republican majority of the General Assembly after it had been discovered that the famous inventor and industrialist George H. Corliss—one of the four Rhode Island electors—was ineligible to vote for president because he held “an office of trust or profit under the United States,” as defined in Article II, Section 1 of the federal Constitution.

Corliss, whose great steam engine was the centerpiece of the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, had been appointed the commissioner from Rhode Island on the United States Centennial Commission, a federal office that disqualified him as an elector. Thus stated the Rhode Island Supreme Court in an advisory opinion to Republican governor Henry Lippitt (In re George H. Corliss, 11 RI 638).

With Corliss declared ineligible, three scenarios were possible: (1) take no action to replace Corliss, in which case the presidential election would result in a tie that the Democratic majority in the House of Representatives, following constitutional guidelines, would break in favor of Tilden; (2) give the position of elector to the next highest vote-getter (i.e., one of the four Democratic electors); or (3) revive the original eighteenth century procedure whereby the General Assembly chose the presidential electors.

The decision was not difficult for Rhode Island’s astute Republican Party leader, Senator Henry Bowen Anthony, the publisher of the Providence Journal and the former president pro tempore of the U. S. Senate. Anthony and his party chose door number 3 to the presidency, whereby Governor Lippitt used his constitutional power to call a special session of the legislature. It met in grand committee and named Republican William Smith Slater (a nephew of Samuel) as Rhode Island’s fourth elector. As the last elector in the nation to be thus designated, Slater cast his crucial vote for Hayes. In view of the Rhode Island situation, 21 electoral votes were in serious doubt after election day 1876, rather than just the 20 scrutinized by historians of that tumultuous episode.

This is the Rhode Island election ticket for the electors for the Hayes-Wheeler Republican ticket. George H. Corliss, the famous Rhode Island inventor, was disqualified as an elector, creating an electoral college controversy. Samuel G. Arnold was a distinguished Rhode Island historian. The image is from Rhode Island Election Tickets: A Survey posted on URI’s Digital Commons website at http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/lib_ts_pubs/17/ The survey was conducted by Russell J. DeSimone and Daniel C. Schofield.

Rhode Island’s important role in that tight contest should prompt us to examine the current demand by some Rhode Island reformers that we abandon the Electoral College as a means of choosing the president in favor of a direct popular vote. They advocate this change with passion, as if it were a matter of ethics and morality, rather than merely one of political expediency.

Rhode Island has far more influence on presidential elections under the present electoral system. Our four votes are 1/135th of the total cast, whereas our 2010 population of nearly 1,053,000 is a mere 1/293rd of the national total.

If I were a Californian, I would support direct election of the president because that populous state is underrepresented in the Electoral College. If I were a true-blue Rhode Island Republican, I would also support direct election to dilute the impact of Rhode Island’s traditional Democratic majority in presidential contests, and thus deprive the Democratic nominee of four automatic votes.

In sum, Rhode Island is overrepresented nearly threefold in the Electoral College because each state’s delegation is determined by its total number of senators and representatives in Congress, and no state can have more than two U. S. senators, regardless of its population. The Founding Fathers devised this unamendable system specifically to protect the small states. As an historian and a constitutional lawyer, I prefer tradition; as a resident of Rhode Island, a state with nearly zero population growth, I oppose a further diminution of our political influence in national affairs.

[The above article also appears as chapter 6, entitled “When Rhode Island Cast the Deciding Vote for President,” in Patrick T. Conley, Rambles Through Rhode Island and Beyond (Providence: Rhode Island Publications Society, 2016), which was recently published.]

[For related articles, go to Archives and click on the following: “George H. Corliss,” by Patrick T. Conley, and “Collecting Rhode Island’s Remarkable Election Ballots” by Russell J. DeSimone and Daniel C. Schofield.]