Rhode Island has frequently had third parties appear in its statewide elections. Almost always these parties had a single purpose, whether Anti-Masonic, Liberty (opposed to the expansion of slavery), American/Know-Nothing (anti-immigration), Prohibition, Greenback, etc…, and they invariably lasted only a short time.

One such party was the Constitutional Party that appeared in 1834 and faded out of existence in 1837. This party’s purpose was to establish a written state constitution to replace the Royal Charter granted by King Charles II in 1663 and was to a large degree the harbinger of the Dorr Rebellion of 1841-1842. For more than one hundred years the Royal Charter worked well for the colony; at the end of the American Revolution, when all other colonies except Connecticut and Rhode Island shed their colonial status and framed constitutions, Rhode Island merely modified its charter by replacing references to the crown with references to the General Assembly.[1]

After the American Revolution and before the Dorr Rebellion there were a number of failed attempts to convene constitutional conventions or at the least to modify the suffrage requirements under the Royal Charter. The growing dissatisfaction with the charter can be attributed to its fixed system of apportionment (as opposed to being based on changing populations), legislative dominance on the executive and judiciary branches, and limited suffrage. With the coming of the Industrial Revolution in the early 19th century, Rhode Island quickly evolved from an agrarian and maritime economy to a manufacturing one. The northern communities of the state grew rapidly as workers found jobs in mills that were being established along the numerous river ways in that region. Growth in the agrarian communities, primarily in the southern part of the state, was relatively stagnant during this same period. To Illustrate the inequity of representation, in 1842 Jamestown had a population of 335 while Smithfield had a population of 9,534, yet both towns had the same number of representatives.

After Rhode Island entered the United States in 1791, the first call for change failed when a proposition for a constitutional convention was defeated in the October 1797 session of the legislature. Less than two years later, at the June 1799 session of the legislature, the House of Representatives defeated a resolution calling for a convention. And in 1811 a bill to extend suffrage at the June session of the General Assembly, then under the control of the Republicans who generally sympathized with it, but it was defeated at the October session by the Federalists who were then in control of the assembly and generally opposed the measure.

In both 1821 and 1822 the General Assembly put before the state’s freemen the question as to whether a constitutional convention should be called. Both times the question was voted down.

In 1824, progress was made. A constitutional convention was actually convened, the delegates drafted a constitution and voted to recommend it, and the proposed constitution was put to vote in a statewide referendum. It was soundly defeated.

The proposed 1824 constitution provided for a more equitable form of representation in the legislature. Towns with 3,000 to 5,000 inhabitants were to have three representatives, towns with 5,000 to 8,000 inhabitants four representatives, towns with 8,000 to 12,000 inhabitants five representatives, and towns with 12,000 to 17,000 inhabitants were to be allotted seven representatives. No town was to have fewer than two representatives. This formula for representation would have largely (if not entirely) removed the advantage small towns held over the towns with larger populations.

The final tally for this proposed constitution was almost 2:1, with 3,206 voting against and only 1,668 voting for the new constitution. A careful look at the returns show that the rural towns of Portsmouth, New Shoreham, Jamestown, Scituate, Hopkinton, Charlestown, West Greenwich, Exeter, Middletown Tiverton Little Compton, Richmond, and Forster were decidedly against change. By comparison, the larger towns of Providence, Smithfield, Bristol, Cumberland, and North Providence were for the change (Newport was a notable exception).

The vote reflected the split between the expanding industrial north and the stagnant agrarian south. Since the majority of the towns were agrarian and each town had two representatives regardless of its population it was evident that the legislature favored the interests of the more numerous agrarian towns. At this point the agricultural interest was represented by the Democratic Party and the industrial manufacturing centers by the Whig Party. The farming interest was staunchly opposed to change, for it feared loss of control in the General Assembly to the manufacturing interest, which would mean increases in land taxes. As the impact of the Industrial Revolution continued to drive more people to the manufacturing centers for employment, the imbalance in representation would only become more pronounced over the next two decades. (Many of the mill workers in factory towns and tradesmen in cities could not even vote in the referendum due to property qualifications.)

The last attempt at reform during the 1820s came in 1829. That year petitions were received at the May session of the General Assembly from residents of Providence, Bristol, Warren, and North Providence calling for a convention to form a constitution. These appeals were referred to a select committee chaired by arch conservative Benjamin Hazard of Newport.[2] This committee reported back to the General Assembly at the June session. The scathing report recommended that the memorialists have leave to withdraw their petitions. Upon reading the committee’s report in our more enlightened time it is hard to image a more biased way of thinking. The report, primarily the work of Hazard, noted:

There are some who pretend to consider the right of suffrage as an inherent, natural right, which every man ought to enjoy. A man’s absolute, inherent rights, are, or ought to be common to all, without distinction of age, sex, or color: such for instance is the right of private property. Is the function of voting such a right? Is it not, on the contrary, one of those political rights which we derive from the society to which we belong; and which, of course, can only exist, as a right, according to the existing institutions of the Society?

. . . .

It would seem, that men, fond of theories, are ever most attached to those which are most visionary and baseless. Nothing short of such a propensity could, we think, have blinded any rational man to the impolicy of admitting people of colour, upon any terms, in this country, to the exercise of the right of suffrage. Without insisting that the African race labour under any peculiar mental or physical disabilities, it is enough to remark, that different races (if we may not say, different species,) of men, can never be so far assimilated as to embrace the same views, of the common good; or to unite in pursuing the same common objects and interest. What then must be the consequences, when a distinct race of men; and whom nature herself has distinguished by indelible marks; and whom the most zealous asserters of their equality, admit to be, if not a distinct species, at least a variety of the human species: are invested with the right of suffrage; and brought up to the polls to act a part in the political contest with which the country is continually agitated? [3]

Following the defeat in 1829 all was quiet until after the presidential election of 1832, after which a small band of workingmen mainly mechanics and non-freeholders began to meet weekly in Providence’s town hall and give speeches and otherwise agitate in the interest of their cause. A committee of correspondence was formed consisting of William Tillinghast, a barber; Lawrence Richards, a blacksmith; William Mitchell, a shoemaker; William Miller, a currier; David Brown, a watch and clockmaker, and Seth Luther, a house carpenter.[4] Subsequently, several professionals (lawyers and doctors) joined their ranks and this group evolved into the Constitutional Party. It was active between 1834 and 1837. In 1834 it called for a state convention the purpose of which was to confer, draw up and lay before the people the outlines of a constitution. This appeal, like all that came before it, failed. At the June 1834 session of the General Assembly a resolution was adopted calling for a convention, but this call eventually died in committee. Rhode Island historian Jacob Frieze, writing in 1842, said it best in describing these events:

It is unpleasant to question the sincerity even of an individual; and much more so to doubt the good faith of a solemn deliberative body. But, as a faithful historian, we are bound to state honest convictions, be they what they may. The General Assembly, in this instance, gave too much reason for the inference which many drew from their conduct on the occasion, that the call for a convention was a sham movement designed to amuse that portion of the citizens of the state, who were loud in their demands for a constitution and an extension of suffrage. Much of the language uttered in debate was of a bitter, sarcastic, and contemptuous character; and manifested a disposition on the part of the speakers, to resist, at all hazards, every attempt to meet the wishes of those who thought themselves aggrieved, and who demanded redress.[5]

The first convention called by the Constitutional Party occurred at the State House in Providence on February 22, 1834. Delegates from ten towns, Newport, Providence, Smithfield, Bristol, Warren, Cranston, Johnston, North Providence, Burrillville, and Cumberland, were present. A committee was appointed and instructed to meet and report to the full convention those subjects thought proper to be acted upon. Thomas Wilson Dorr, from a wealthy Providence family became a member of the committee and reported a list of nineteen resolutions. These resolutions called for a constitution that would among other things define the power of the legislature, equalize representation in the House of Representatives, improve the judiciary, and extend the right of suffrage. The greatest sticking point was the right of suffrage contained in Resolution #6. It read:

That in the opinion of this Convention all white male citizens of the United States over twenty-one years of age, (excepting paupers and persons under guardianship) . . . should be entitled to the right of suffrage upon paying a tax; and that no person born out of the jurisdiction of the United States should be allowed to vote unless he has first been naturalized according to the Acts of Congress; have been possessed of a freehold estate according to the provisions of the present law, for a term of years, and have resided, previously to voting, one whole year in the State.

In effect the Constitutional Party wanted to expand the right of suffrage to non-landholding native-born citizens but still supported the prevailing state laws that disenfranchised non-white citizens and required naturalized citizens to be in possession of a freehold estate. The Constitutionalists were reform minded but not to the extent of accepting non-whites or naturalized citizens on the same footing as native-born white citizens. Following discussions and acceptance of the resolutions, several committees were created and directed to meet and report when the convention was scheduled to reconvene.

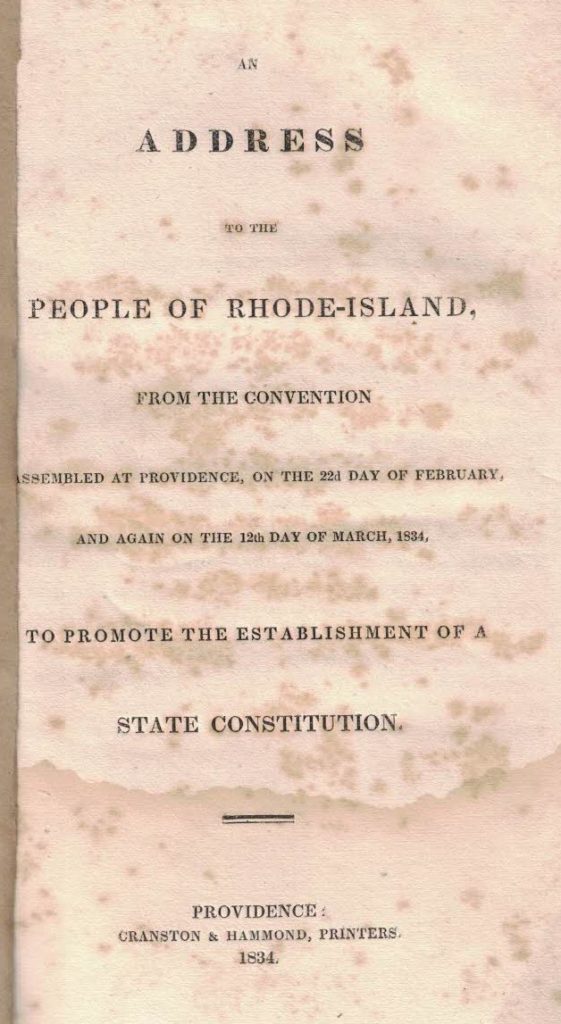

The convention reconvened in Providence at the State House on March 12 at 10 a.m. with delegates from the towns of Scituate and North Kingstown joining the original ten towns. One of the first committees to report was the fifteen-man nomination committee that presented a slate of candidates for general office in the April election. Nehemiah Knight and Joseph Cross were approved as the nominees for governor and lieutenant governor, respectively. Next the committee created to prepare the Constitutional Party’s principles reported. This committee consisted of five delegates, all lawyers, Joseph K. Angell, Thomas Wilson Dorr, Thomas Rivers, Christopher Robinson, and William H. Smith. The report, written primarily by Dorr with assistance from Angell and Smith, was presented by Dorr.[6] In effect the report summarized the tenets of the Constitutional Party and following the convention it was printed as a sixty-page pamphlet. (See Figure 1.) The principal topics of the report were Definition of a Constitution, Character and Defects of the Charter as an Instrument of Government, Inequality of Representation, Extension of Suffrage, Qualification of Voters in each of the States, and Improvements of the Judiciary.

Figure 1: Cover page of the pamphlet entitled “An Address to the People of Rhode Island from the Convention Assembled at Providence, on the 22nd day of February, and Again on the 12th day of March, 1834. The Principles of the Constitutional Party were summarized in this report. (Russell J. DeSimone Collection)

While the Constitutionalists were making great efforts, the General Assembly was also active. On January 15, 1834, the Mayor and City Council of Providence submitted a memorial to the General Assembly noting that the city had one-sixth of the state’s population, one-seventh of its voters, and one-fourth of its wealth yet it only had one-eighteenth representation in the House of Representatives. A legislative committee was appointed to consider the subject. During the June session a motion calling for a constitutional convention was carried. As worded the bill called for either amending the present (the charter) or proposing a new state constitution.

In late August and early September, a heated debate in the House occurred between those who simply wanted to amend the charter (led by Benjamin Hazard) and those who wanted to draft a new constitution (led by Thomas Dorr). Hazard felt that “[a] few simple and obvious additions only will be sufficient” to the charter. He had repeatedly accused the reformers of fearing amendment to the charter stating “this is precisely what these free suffrage people are afraid of. They know that if the charter is once amended there will be an end to all their revolutionizing projects.”[7] Dorr retorted:

But the member from Newport exclaims, “Free Suffrage,” “Universal Suffrage,” and repeats and reiterates them with every variety of tone and emphasis: he charges the Constitutionalists in the House with a design to introduce “Universal Suffrage,” and failing in the proof of the assertion returns again to the war-cry of “Universal Suffrage.” I will venture to predict that, if not exhausted, he will repeat those words twenty times more before the conclusion of this debate.[8]

The convention first met in September, adjourned several times thereafter, and met last on June 29, 1835. Because of a lack of general support, the effort for a new constitution simply petered out. The Constitutional Party would continue to exist until 1837 when it too petered out.

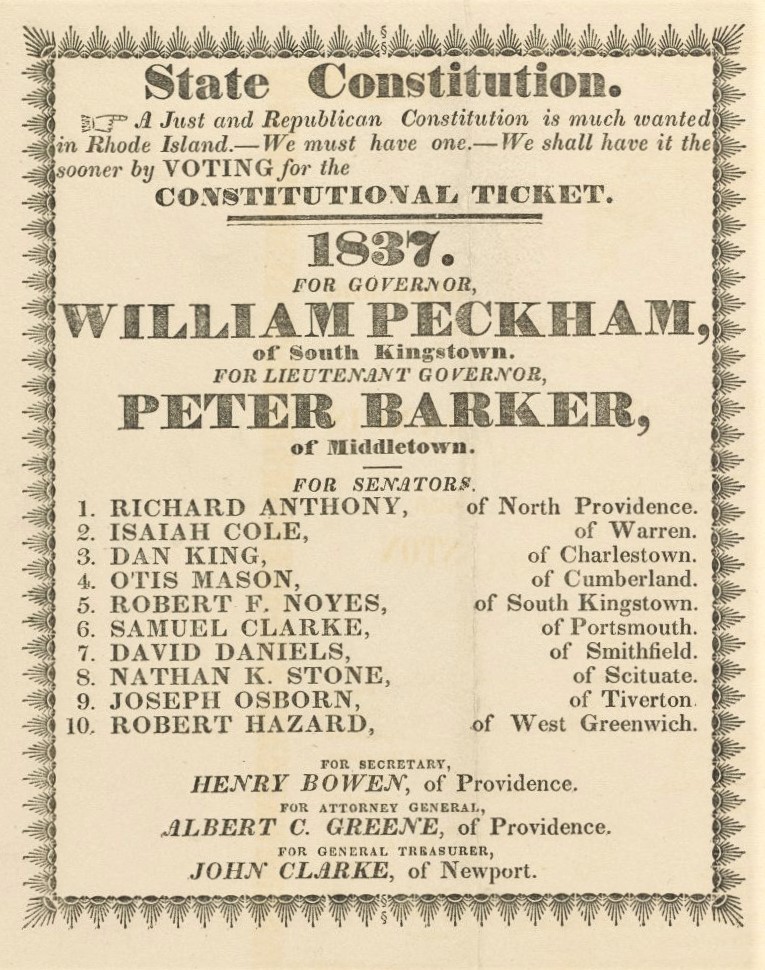

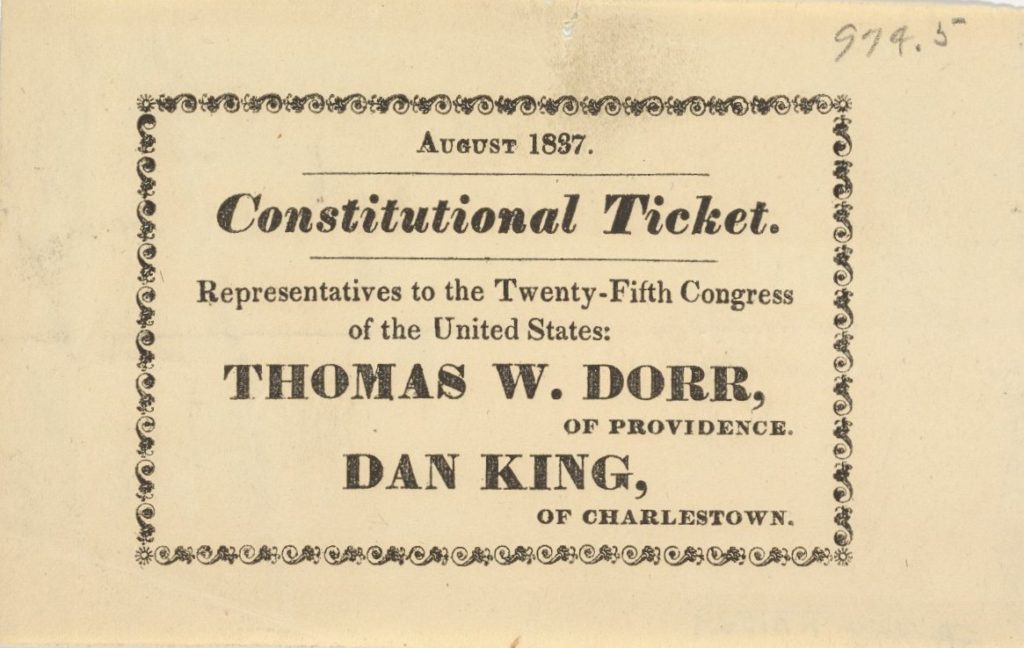

The Constitutional Party never mustered large support, but it did manage to offer candidates for election and even established a newspaper to promote its objectives. The first state election in which the party offered a slate of candidates was in 1834 when it issued a Constitutional Ticket. Interestingly, the candidates on the ticket were a mix of Whigs and Democrats who were already running for office on other tickets. In subsequent years, the party offered other candidates it felt were friendly to the party’s objectives, but invariably these candidates never received many votes. In 1837, its last year of existence, the Constitutional Party ran tickets for statewide office as well as for U.S. representatives. (See Figures 2 and 3). In all the elections in which it participated, the party received little support from the electorate.

Figure 2: 1837 Constitutional Party ticket for statewide office. William Peckham lost by a wide margin to incumbent governor John Brown Francis (Russell J. DeSimone collection).

Figure 3: The Constitutional Party fared poorly in the election of August 1837. Thomas Dorr received only 72 votes and Dan King received 25 votes out of a total of 7,615 votes cast (John Hay Library, Brown University).

The year 1834 saw the arrival of several newspapers dedicated to constitutional reform in Rhode Island. The earliest was The Voice of the People first published on January 29, 1834. In its first edition, it noted “The Voice of the People will be published by a Committee appointed by the friends of a State Constitution.” Edwin Field’s State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations at the End of the Century states that this paper, published by a Mr. Doyle, was silenced after only a few issues.[9] The first issue noted that copies had been sent to various parts of the state and to subscribe the reader was requested to send payment of one cent per number or forty-five cents for fifty copies care of E. & J.W. Cory at No. 9 Market Square in Providence. The partnership was dissolved in February 1834, which may account for the demise of this newspaper.[10] The first issue stated “From our slumber, we devote the hours [italics in original] which may be required to fill this little sheet. – Rhode Island is the last link of the chain on which the rust of Aristocratic government remains. Ours be the labor to rub off the stain – thine the glory to wear it bright and transmit the radiant zone to posterity.”

The reference to Rhode Island’s aristocratic government would come into play again during the Dorr Rebellion when the Rhode Island Suffrage Association would claim the Royal Charter of 1663, under which the state still operated at the time of the Dorr Rebellion, had led to an aristocratic style of government. At a meeting in Providence “of the friends of a Constitution and Extension of Suffrage” on February 19, 1834, the following resolution passed:

That we deem it a duty which we owe to the people of this State to declared explicitly, that the paper published in this city, called The Voice of the People, in our opinion, does not, in some respects, proclaim the voice of the People and that members of the Constitutional party hold themselves in no way accountable for any article that has been, or hereafter may be published, in said paper, and that no Committee has been appointed by the Constitutional party, to superintend the publishing of that paper, as may be inferred from a statement in said paper.[11]

Without the support of the Constitutional Party it is no wonder that the newspaper failed after only one or two issues.

Two months after the appearance of the Voice of the People another newspaper, the Rhode Island Constitutionalist, made its debut. The first issue ran a poem entitled A Political Hymn, which in its stanzas raised several questions. The first stanza read:

And must the CHARTER die?/Its tot’ring frame decay?

And with its Royal author lie/Amould’ring in the clay?

This newspaper, published by the State Committee of the Constitutionalist Party and printed by Cranston and Hammond of Providence, was also short lived, with but two editions, March 12 and April 7, 1834. This newspaper, like the first, suffered from a lack of financial support. Support came mainly in the form of subscriptions, but the party was small and did not have sufficient members to underwrite the enterprise.[12] In a letter from Thomas Dorr to Christopher Robinson, both members of the Constitutional Party, Dorr urged Robinson to find subscribers. Dorr wrote, “Messrs. Cranston and Hammond are to publish 2 more numbers of the Constitutionalist of 1,000 copies each before the election. . . . All the friends of a Constitution, wherever they are, ought to make haste to send in their names for the Constitutionalist. Urge along those who are hesitating.”[13] The appeal had little effect, as the paper had only one issue remaining before closing. The Constitutional Party had to wait nearly five months more before another newspaper would become the party’s official newspaper. That paper would be the Northern Star, and Constitutionalist. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4: Mastheads of three Rhode Island newspapers all in support of a written state constitution. The Northern Star, and Constitutionalist, published in Warren, became the Constitutional Party’s official newspaper in 1834 (Russell J. DeSimone Collection)

The Northern Star had been published since 1826 at Warren, with slight variations in its masthead, including the Northern Star and Warren and Bristol Gazette, and the Northern Star and Farmers and Mechanics Advocate. Its publisher for most of the time was Charles Randall, who also happened to be a member of the Constitutional Party.

The story of how this paper became the official organ of the party is found in several surviving letters from Charles Randall to Thomas Dorr. The first letter of note was dated June 23, 1834, in which Randall in a postscript mentions to Dorr, “I should be pleased, Sir, to receive from you, communications on this important subject, – as I devote a portion of my paper, every week, to the good cause.”[14] While not an out-and-out proposal by Randall to become the official organ of the party, the offer did at least look to fill a void in party rhetoric. The actual proposal by Randall came two months later in the form of a letter dated August 11. Randall stated:

I understand that there is not the most distant prospect of making any arrangements about establishing the Constitutionalist. I have thought that I would make this proposal to you, in case you have given up the plan of starting it: That I would alter the name of my paper so that it should read “The Northern Star and Rhode Island Constitutionalist” – and devote from 4 to 6 columns each week to the subject of Constitutional Reform.

Randall then discussed the possibly of receiving the list of subscribers of the defunct Constitutionalist but only if in Dorr’s discretion it did not prejudice the cause. Randall explained that many friends in the western part of the state had signified their intention of subscribing to his paper were the Constitutionalist not to go on. He ended his letter with the postscript, “I wish you to understand that if there is any prospect of starting the Constitutionalist I do not wish to interfere in the event.” Randall’s offer sparked a chord, as Dorr annotated on the letter, “Randall came up; and arrangement made to publish his paper as Constitutionalist, Aug. 16.”[15]

A week after the meeting between Dorr and Randall, the Northern Star, in its August 23, 1834 edition, reported “The State Committee of the Constitutionalist party have transferred the subscription list of the Constitutionalist, two numbers only of which have been published, to the editor and proprietor of the Northern Star, printed in Warren, with the understanding that his paper will be hereafter continued under both names.” Possibly reflecting dwindling support for constitutional reform in the fall of 1834, Randall wrote to Dorr on October 22 to discuss the distribution of the newspaper and address the small number of subscribers. He wrote:

So far, I only retain about 150 of the Constitutionalist subscribers. Some of them [newspapers] were sent 6 & 7 weeks before any returns were made, and I continue to receive every week some sent back. How many will eventually continue I cannot say, but I have sent you enclosed $10 – and will run the risk of it. From Pawtucket, all but Mr. Weeden’s were returned – from Woonsocket & Cumberland Hill the whole of the list, and also from Crompton Mills.

Obviously the $10 that Randall sent Dorr was in consideration for providing the subscription list of the Constitutionalist Party newspaper. Presumably, the money went into the party’s coffers. Randall ended his letter to Dorr with a postscript, “If I should succeed in getting any of these subscribers hereafter, I will pay on the same proportion as what we talked of. How did the constitutional folks pay up to Messrs. Cranston & Hammond?”[16] Regardless of the diminishing number of Constitutional Party subscribers to his newspaper, Randall stuck with its new title until the demise of that party in the fall of 1837. Randall remains to this day one of Rhode Island’s unsung heroes promoting constitutional reform.

After the 1834-1835 failure of the party to establish a new constitution, matters quieted down, and it would not be until 1837 before there was renewed activity to affect reform and run Constitutional Party candidates in both the state and congressional elections. Still, throughout this time. Randall’s newspaper continued to publish news and occasional screeds on constitutional reform. Whether it continued to be backed by the Constitutional Party is unclear.

One longtime adherent of reform emphasized that a reform newspaper needed to hail from Providence. Dr. Metcalf Marsh of Slaterville wrote to Thomas Dorr on April 24, 1835:

I need not say that it is essential to the success of our party that we should have an able paper published in Providence to advocate our cause this is always a well-established fact and the only question is whether it can be accomplished at this time. This is the point to which I would particularly solicit your attention. I would suggest a plan for the immediate establishment of a paper which if not the best would at least as I think be practicable and submit it for your consideration. Let the possible cost of publishing a paper for one year be estimated and divide that sum into one hundred shares and I am disposed to believe that those shares would with a little exertion be taken up.[17]

Since no newspaper was ever issued from Providence along Marsh’s proposed plan, the Northern Star and Constitutionalist of Warren continued to be the only paper in Rhode Island wholeheartedly committed to constitutional reform.

What killed the Constitutional Party? The answer is complex, but more than any one factor was its call for an extension of suffrage. Had it just pushed for a written constitution to replace the outdated charter and relief of the ill-apportioned House of Representatives, it may have had a chance, although the influential Benjamin Hazard opposed anything but amending the charter. As much as the party wanted to be viewed as committed to more than concerned with suffrage extension only, it was perceived by many as just that. In its address “To the People of Rhode Island” published in August 1834, the party ended its address with “all editors of newspapers, who have published any comments, or communications upon the objects and proceedings of the ‘Constitutional Party,’ especially such as have had a tendency to misrepresent them as being a ‘Universal Suffrage’ party, are requested to copy the present statement.”[18] At that time, being labeled as the universal suffrage party was a sure way to undermine the party’s success. Rhode Island was not yet ready for universal suffrage.

The Constitutional Party did not achieve its stated objectives to establish a written constitution, limit the role of the legislature, reapportion representation to the House of Representatives, extend suffrage, and reform the judiciary. However, it did help pave the way for the events that followed in 1840—the establishment of the Rhode Island Suffrage Association and the ensuing events of 1841 and 1842 that led to the People’s Constitution and the Dorr Rebellion. To a degree it can be argued that the Constitutional Party was instrumental in the establishment of the state’s constitution that was drafted and ratified in late 1842.

[Banner image: The I837 Constitutional Party ticket for statewide office (Russell J. DeSimone Collection)]

Notes:

[1] Connecticut retained its royal charter until 1818 when it was replaced by a written constitution. [2] Charles Congdon in his Reminisces of a Journalist (Boston, 1880), at 105, described Hazard as “a hard-headed old lawyer with a bottomless contempt for political innovations . . . .” [3] Benjamin Hazard (for the committee), Report of the Committee on the Subject of an Extension of Suffrage (Providence, 1829), 5,13, and 20. [4] Jacob Frieze, A Concise History of the Effort to Obtain an Extension of Suffrage in Rhode Island; from the Year 1811 to 1842 (Providence, 1842), 27. [5] Ibid., 30. [6] Elisha R. Potter, Jr., in his Considerations on the Questions of the Adoption of a Constitution and Extension of Suffrage in Rhode Island (Boston: Thomas H. Webb, 1842), p. 27, credits Thomas W. Dorr for writing the report with historical input from Joseph K. Angell and statistical input from William H. Smith. Patrick T. Conley, in his Democracy in Decline, Rhode Island Constitutional Development, 1776-1841 (Providence: Rhode Island Historical Society, 1977), republished by the Rhode Island Publications Society, 2019, p. 256, also suggests that Christopher Robinson provided input on suffrage. [7] Manufacturers and Farmers’ Journal, September 1, 1834. [8] Ibid., September 3, 1834. [9] Edward Field, State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations at the End of the Century: A History (Boston: The Mason Publishing Co., 1902) vol. 2, 582. This no doubt was a reference to Thomas Doyle who was a member of the Constitutional Party’s convention of 1834 and father of the future mayor or Providence. [10] H. Glenn Brown and Maude O. Brown, A Directory of Printing, Publishing, Bookselling & Allied Trades in Rhode Island to 1865 (New York: New York Public Library, 1958), 50. [11] Providence Journal, February 20, 1834. [12] William Wheaton in a letter to Dorr noted “You seem to think that the Constitutionalist paper cannot be published in consequence of the deficiency of subscribers.” Letter dated May 1, 1834, Sidney Rider Collection – Dorr Correspondence Box 1 Folder 19. [13] Letter from Thomas Dorr to Christopher Robinson, April 2, 1834, ibid., Folder 18. [14] Charles Randall to Thomas Dorr, June 23, 1834, ibid., Folder 21. [15] Charles Randall to Thomas Dorr, August 11, 1834, ibid., Folder 27. [16] Charles Randall to Thomas Dorr, October 22, 1834, ibid., Folder 22. [17] Metcalf Marsh to Thomas Dorr, April 24, 1835, ibid, Folder 23. [18] Providence Journal, August 21, 1834.Suggested Further Reading:

For an in-depth look at the rise and fall of the Constitutional Party in Rhode Island, the reader is referred to Patrick T. Conley’s Democracy in Decline, specifically chapter ten, “Workingmen, Constitutionalists and the Convention of 1834,” and chapter eleven, “The Constitutional Party in Decline.”