I don’t know if I was actually conceived on a train, but my mother was carrying me when she went back and forth on a Southern Pacific train between home in San Francisco to her parent’s place in a lovely little gold rush town 135 miles away. Auburn was right on the SP’s transcontinental main line between San Francisco, California, and Ogden, Utah. The train was her carriage of choice because my father, a doctor, worked for the Southern Pacific Railroad at its big hospital in San Francisco. One of the perks of employment with the SP was a family railroad pass. That little card started me on a train journey that was over 500,000 miles long, through 27 countries, ending up, of all places, in Wakefield, Rhode Island.

As I was ruminating over what to include in this two-part article, it struck me that kids were much more independent in the ‘50s than they seem to be now. As soon as I was 16, I could use the pass to travel on SP’s second-class trains by myself-no parents needed (or wanted). The week of my 16th birthday, I started a new game. The game was as soon as school let out on Friday, to hot-foot it to the SP station downtown and take the first departing train. The object of the game was to transfer between trains in such a way that I would go as far as I could before having to turn around to get back for the start of school on Monday. I am proud to note that on one memorable weekend, I made it as far as El Paso, Texas (I have a picture to prove it). Unfortunately, I must confess that I did not make it back EXACTLY on time for first class on that Monday, and had to serve detention with the other hoodlums and juvenile delinquents. It was worth it, though.

After high school, I spent the rest of my academic life on the Pacific Coast, all the way through Ph.D., and two years of post-doc work at the University of Washington. There was one exception. I suffered through an endless and awful freshman year at Rensselaer Polytechnic, in Troy, New York.

From the editor: Frank Heppner as tourist in Venice. His sense of humor is reflected in his photographs as well as in his writing! (Frank Heppner Collection)

Unlike today, when freshman are delivered to their new dorm home by their loving parents hauling a trailer with all their sports equipment, clothes, electronics, etc., I loaded all my worldly possessions into a small suitcase, and at the age of 17 my parents took me to the SP station in Berkeley, where I boarded the first of many trains that would take me almost 3,000 miles, by myself, to upstate New York.

I had been #3 in my high school graduating class, but it didn’t take long for me to start running a 1.6 average at RPI. I was surrounded by geniuses! And what was worse to the point of total humiliation, some of those geniuses were incredibly good looking AND jocks. I decided to transfer to Berkeley as a sophomore, which I accomplished, but only after getting two A’s in courses in summer school.

Master’s and Ph.D.’s followed then I got a post-doc position at the University of Washington. But the fly in my ointment was beginning to gnaw its way to the surface. I needed to find a university faculty job when my post-doc appointment was over in Spring, 1969. Academic jobs in science were fairly easy to find in those days. But jobs on the West Coast were for some reason almost non-existent at the time. I started looking at the main employment ad source for biologists, Science magazine. Plenty of positions all over the country, but not the West Coast. So I started to panic. If I didn’t get something nailed by end of April, I wouldn’t have any academic job for next year, and I’d be starting a new career in fast food.

It was at that time that a rather strange ad came out—it was for a tenure track Assistant Professor of Biology at the . . . University of Rhode Island. I didn’t know anything about Rhode Island, except that I’d heard it was in New York. The hiring ad was odd, too. Such ads usually specified a specialty field-physiology, anatomy, birds, snakes, etc. But this ad just said the professor would teach a general biology course. Normally, alarm bells would ring, but I was in no position to be fussy.

So I called the listed number, and talked to a person who practically OOZED enthusiasm: oh, they were looking for someone with my EXACT qualifications, they’d love to have me in Little Rhody (Little Rhody?) etc.…. So, like in The Godfather, which was based on characters who lived and worked in Rhode Island, they made me an offer I couldn’t refuse.

At the end of that August, I tearfully bade Seattle goodbye, and I decided to take the train all the way from Seattle to Kingston. I went to Chicago on the Empire Builder, and transferred to a New York Central train-not the 20th Century Limited, but not bad. At New York, I transferred to a Penn Central train. Once on board, you could smell the manure odor of the previous occupants: cattle heading for their doom outside Chicago.

The train rumbled and jerked along the poorly maintained track for hours, then it creaked to a stop, and the conductor called out “K-ii-ngston.” I had been expecting a quaint, beautiful little country station. In contrast to the Southern Pacific’s beautifully maintained stations, Kingston Station appeared as a near-death building that looked like it was a day away from the knackers.

The instant I stepped off the stairs of the coach of the rattletrap train from New York City to begin my 40+ year career as a Professor of Zoology at URI in Kingston in 1969, I knew my life was going to be different.

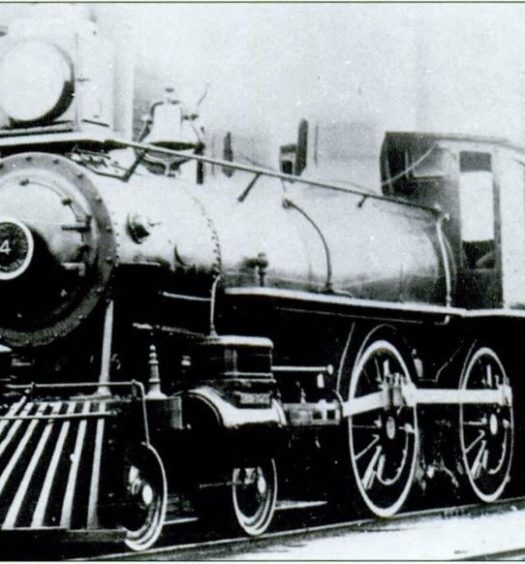

Kingston Station in 1875, the year of its completion and initial operation, with a steam locomotive (former collection of the Rhode Island Railroad Museum)

I arrived but a few days before classes began, and only then discovered what I would be teaching: Bio 2, a 900 student, non-major General Biology class. Both semesters. A different upper division lab course each semester, ditto for a graduate course–six courses a year. My salary was $11,500 per annum. Not bad for the day.

Two years later, I bought a Victorian house in downtown Wickford for $21,000, and essentially rebuilt it to brand new for another nine grand–so the total cost for a brand new house was 2.6 times my annual income. But new Assist Professors today make about $129,000, and the same house is listed for sale for $685,000, or 5.3 times their annual income. So even though I still didn’t have a railroad pass, I could easily afford essentially unlimited paid train travel. After a couple of years, I started to get invited to give papers at distant universities, with transportation on their dime. Guess what form of transportation I usually used?

However, as you might imagine, for my first couple of years I was a bit busy with work and getting used to Rhode Island’s little peccadillos. Take, for example, food. The city where I grew up, San Francisco, is one of the three great dining cities of the world, the others being Paris and New York. From that environment surrounded by world-class restaurants I came to—Giro’s (not the present one). The original Giro’s was almost exactly a mile from campus on Kingstown Road. Not surprisingly, it served Italian food. The first time I went there, I asked the waitress (that’s what they were called then) what kind of wine she had. Very proudly, she said, “Oh, Sir, we have several kinds. Red AND white!” You don’t often see a grown man cry in public, but you would have then. It wasn’t until I discovered the late-lamented Red Rooster Tavern in North Kingstown that I began to approach restaurant dining with something other than fear.

After a couple of years, I got my act together enough to start a bit of rail traveling AND railfanning. This was before the internet, email, or anything similar, and I think the way railfans exchanged information was by somehow finding out about organizations with regular meetings, attending them, and swapping information there.

I heard that there was some kind of locomotive work facility by the Penn Central tracks north of Providence. I climbed in my stylish Volvo 142, in which I had made my last transcontinental trip, and headed north. The neighborhood got grimmer and grimmer, until finally I was at the door to hell, otherwise known as the Penn Central Charles Street roundhouse, now gone without a trace.

The first engine I saw looked like a corpse fresh out of a coffin. Built in 1951, former New York Central (now Penn Central) 5260 sat forlornly on a rip track (technically, a track where minor repairs were made). But this poor, decrepit guy was literally going to be ripped apart to be made into spoons.

If that wasn’t depressing enough, I stopped by the Providence Train Station to see if it looked as bad as Kingston Station. It once had been a been a beautiful building, but now the interior was like a cave, complete with echoes. A couple of forlorn ticket windows served the occasional lonely passenger.

However, Rhode Island had its own commuter train, from Providence to (I believe I recall it correctly) New London, financed by Rhode Island’s Department of Transportation, and run by Penn Central. The commuter train was called RI 508, and it stopped at Kingston Station. It was usually two cars and a locomotive. Often there were only a couple of passengers.

Kingston Station, in poor condition, in the 1960s, with locomotive in front (former collection of the Rhode Island Railroad Museum)

In the mid-‘70s, in a last ditch effort to gain publicity as well as riders for the 508, a group of URI folks staged a (fake) race between a Datsun 260 race car and a commuter on the 508 from Kingston to Providence. The idea was to show South County commuters that the train was faster than the car. A race car driver (complete with helmet) drove the car, and a representative (probably not a volunteer) from the state Department of Transportation rode along to be sure no highway laws were broken. The train competitor was a nice, middle-aged lady who was one of the last regular 508 riders. The race started as soon as the 508 stopped at Kingston and the lady boarded. The 508 beat the racer by a minute or so.

The victory was for naught. Within a few years the 508 was in train heaven, killed by the completion of the major part of the Route 4 highway in 1972. Route 4 also killed southern Rhode Island as an example of rural New England. Before Route 4 was finished, it was not practical to commute to Providence from Wickford or Wakefield. After Route 4, subdivisions in South County began to appear like ticks on a raccoon.

In the ‘70s my mother was in chronic poor health in San Francisco, so I went to see her (by train) three to four times a year. By the time she passed in 1977, I had been across the country on all the major transcontinental train routes, from the Northern Pacific near Canada, to the Atchison, Topeka, and the Santa Fe near Mexico. If you are over 70, you cannot say “On the Atchison, Topeka, and the Santa Fe” three times in a row without starting to sound like Judy Garland.

I fairly quickly exhausted the railfanning possibilities in the state, which primarily consisted of visiting abandoned rights-of-way and a handful of tourist lines. It was depressing. Then in 1973 something happened that would change the railfan (and passenger railroad) scene in Rhode Island dramatically. To understand the how and why, you have to understand why URI was different both before and after.

I was the first member of the old Department of Zoology to have received a Ph.D. from an institution west of the Hudson. Most of the new faculty were not from Rhode Island (or even New England) and were very young and ambitious. We were not aware of fusty old Rhode Island traditions and were anxious to try new things. We were also not under the same pressure to bring in outside grants that plague today’s young faculty. Coming out of the ‘60s, we had a strong volunteer ethic, so that when a community problem appeared, it was not difficult to generate volunteers.

As URI’s horizons expanded, more and more people began to take the train out of Kingston. Going along with this was the realization that Kingston Station was an embarrassment to the community.

In 1973, sufficient numbers of the URI community regularly took the cattle trains stopping at Kingston that there began to be an awareness that neither the station owner, nor the railroad serving it, would ever spend a dime on it. That’s when two activists on the campus, the Rev. John Hall, Pastor of the campus Episcopal church, and Barbara Dirlam, wife of a very politically active URI faculty member, Joel Dirlam, put a notice in the campus newspaper calling for a meeting to discuss what might be done with the station. That meeting represented the first hour of the tens of thousands of hours volunteers spent in getting the station restored. They called themselves the Friends of the Kingston Station. From the little I’ve seen of contemporary campus life, it’s hard to imagine such a group forming today.

Kingston Station was worth saving for many reasons, including that it is (and remains today) the oldest, continuously operating wooden passenger train station in the United States. It was completed in 1875 and passenger operations began shortly thereafter. Arguments have been advanced for stations at New Canaan, Connecticut (opened in 1868), and Jackson, Michigan (opened in 1873), as being a couple of years older, but passenger service was discontinued in New Canaan in 1971 (and though it returned it was spotty thereafter) and the Jackson station is made of brick. At worst, it is the third-oldest continuously operating passenger train station in the country, and the oldest on the East Coast.

How successful the efforts of the Friends of Kingston Station would ultimately be will be discussed in the next installment.