When I gather with other octogenarian rail enthusiasts in Rhode Island, either in person or online, we always come around to the same topic: the Younger Generation. Invariably, three observations are made: 1. Their universe is contained in the memory of their phones. 2. They have a limited vocabulary, ranging from “amazing” to “awesome.” 3. They don’t volunteer for anything except sports. While all three are arguable, when I think back to the beginnings of the restoration of Kingston Train Station in the ‘70s, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that the times really were different.

Kingston Station is definitely worth saving. It is now the oldest continuously operating wooden passenger train station in the United States. It is the second oldest continuously operating passenger train station in the U.S. (only the brick station in Jackson, Michigan, is older). The simple, but attractive Victorian country-style building looks today almost exactly the way it was when its construction was completed in 1875. But in 1972, its future was unpromising.

When Barbara Dirlam and John Hall put out an invitation for a meeting to discuss restoring the station in 1972, about a dozen people showed up for the first meeting and most of the time was occupied with questions about the station. Who owned it? Who operated it? Was it still used much? Why was it in such deplorable condition? If it was not possible for the owner to restore it for some reason, could volunteers do it? At the end of the meeting, it was decided to continue the discussion. In 1973, the group established the Friends of the Kingston Railroad Station (usually abbreviated simply as “The Friends”).

As it turned out the answers to these apparently simple questions were far more complicated than anyone imagined because they involved several bureaucracies, which (much to our dismay) sometimes competed with each other. This was the situation as best we could figure it out at the time. The station was owned by the Penn Central Railroad, which was a consolidation of the Pennsylvania, New York Central, and New Haven Railroads. The New Haven had formerly operated the line through Kingston. Alas, the Penn Central was deep in bankruptcy, and although it both owned and operated Kingston Station it had no interest in spending a nickel more than necessary on either maintenance or operations. Complicating the situation, as if it wasn’t complicated enough, “Amtrak” was the name for the new semi-governmental agency that would soon take over the operation of passenger trains from the railroads that had previously run them.

So, the Penn Central owned the station, but it was about to be taken over by Amtrak. Neither were interested in spending money on a semi-rural station. However, the spirit of volunteerism was alive and well at the time, and the Friends soon decided to take on the restoration as a community volunteer task.

David Jacobs standing in front of the ticket counter inside Kingston Station, November 1974. Even today, its interior, as well as its exterior, is little changed since 1875 (David Jacobs)

Early on, there was a realization that even a minimal restoration would be expensive, and probably beyond the range of contributions by volunteers alone. Because so many of the original members were associated with URI, they were familiar with government grants and contracts, and they recognized that the majority of restoration funds would have to come from that source. It did not hurt that Rhode Island senator Claiborne Pell, a senior member of the U.S. Senate, had been a rail enthusiast for decades; he would be very helpful in securing government funds.

To become eligible for some of these funds, it was necessary that the building be placed on the National Register of Historic Places, typically a drawn out (and painstaking) process. In perhaps record time, the station was placed on the National Register in 1975. This was a critical step, not only because it made fund-raising easier, it also made it almost impossible for the station to be torn down in the future, even if it were in poor shape.

Matters proceeded at an astronomically fast pace by today’s terms, and during a week in June 1974, 180 members of the South County community crawled over the station, chipping, scraping, and painting, The new paint scheme was not the historical one, but a pale blue one selected by the participants.

Needless to say issues came up. Both Amtrak and Penn Central were heavily unionized. If the community did work on the station, they would displace unionized workers, a normal stumbling block. So The Friends began lengthy discussions with all the unions involved, and somewhat remarkably, a workable compromise was reached. The Friends would hire one unionized railroad guy to be a “safety inspector.” A member of a different union was the “flagman,” who kept volunteers away from the tracks when an express train came through without stopping.

Penn Central donated $10,000 toward buying paint and renting equipment. It also agreed to restore the interior at its expense once the exterior was done, a promise Penn Central kept.

In 1975, a massive celebration was staged at the station to mark the completion of the station project, and the turnover of the operation of the station to Amtrak. The ownership of the station, however, rested with the Department of Transportation of the State of Rhode Island. It later turned out that there was no agreement between Amtrak and RIDOT establishing a rent for Amtrak’s use of the property.

I was one of the first Friends and am one of four or five survivors of that early group. The early Friends really was a team effort; each of us had something different to contribute because of our backgrounds. I was a hardcore railfan. There was a university administrator, a lawyer, a politician, an engineering professor, a horticulturalist/government worker, and even an Amtrak employee. All of us were used to working in a committee, and unlike many volunteer organizations, we didn’t have battling egos.

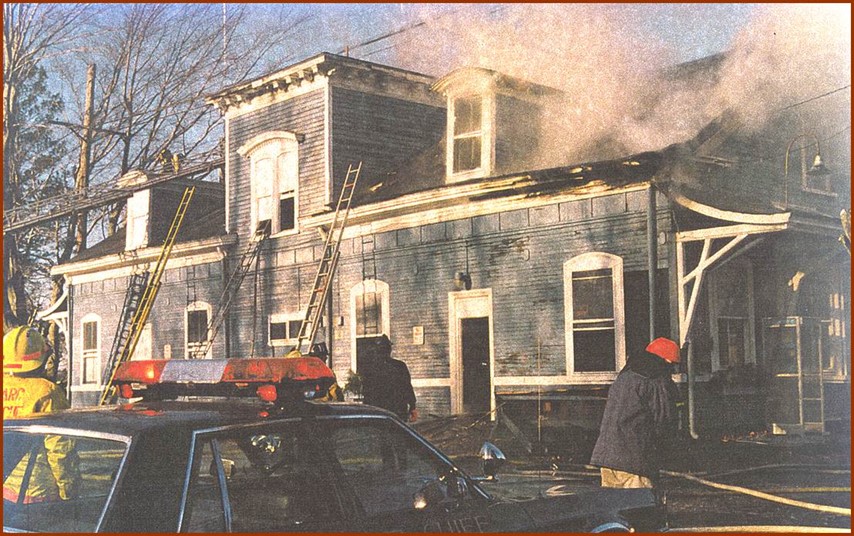

The West Kingston Volunteer Fire Department is credited with saving Kingston Station after it caught fire in 1988 (former Rhode Island Railroad Museum collection)

The years passed. Although patronage kept going up, routine maintenance went down, and in 1988 there was a near disastrous fire that forced the closure of the station. Amtrak’s first response was to decide to tear down Kingston Station and eliminate the Kingston stop. Panic set in among railfans and rail passengers. But Jack McCabe, a station agent, discovered the National Register of Historic Places paperwork, which forbade the owner of a historic structure from tearing it down. The Friends revived itself, and after what seemed like 10,000 hours of mind-numbing work dealing with government agencies and Amtrak, $2,000,000 was found to restore the station. By this time, the passenger rail business at Kingston Station had improved so much that other structural improvements were called for. Today, in total, almost $30,000,000 has been invested in the Kingston Station area, including an overpass, high level platforms, a high-speed passing track (for the Acela today), and several additional sidings, plus vastly improved landscaping around the station.

As is true about almost everything connected with Kingston Station, the later history of The Friends has been complicated. For many years, the group operated a small railroad museum in the station, which turned out to be the state’s most popular small museum. I was glad to serve as the museum’s curator, keeping track of displays and making sure donors received thank you letters.

Some Friends of Kingston Station in 2010 in the west wing when it was used as a railroad museum. Frank Heppner is on the far left and Jack McCabe is sitting in front in a white shirt (Jack McCabe)

Sadly, the museum was forced to close after a person of influence in one of the bureaucracies determining policy for the station decided a second waiting room was more important than a museum. That closure eliminated many of the attractive volunteer positions offered by the Friends, and membership gradually slid to a non-supportable level. The handful of survivors decided to officially close The Friends and donate the funds it had gathered over the years to worthy causes. Meanwhile, the second waiting room is used infrequently.

However, as has always seemed to be the story with The Friends, when things are at their blackest, a headlight can be seen down the track. As part of the 300th year anniversary celebration planning for the town of South Kingstown, a committee was formed to look into restoring the old railroad signal tower next to the station. Someone on this committee knew about The Friends, contact was made, and miracle of miracles! The Friends of the Kingston Station name was revived and active progress is now being made to achieve this new goal.

The Friends of Kingston Station has been revived in order to make an effort to restore the Signal Tower (shown here in August 2022) (Christian McBurney)

The most challenging task this new group will face will be recruiting newer, more energetic young members. I was born before Pearl Harbor and still remember seeing B-36 bombers flying overhead. Several of our other longtime members were fans of the Beatles when they first came to the U.S. Our ability to work on scaffolding is now somewhat limited. It will not be easy to pry the younger generation away from their devices, but I think that if we can show potential Friends that their accomplishments will be real, not virtual, we’ll be able to continue the near half-century tradition of service by The Friends of the Kingston Station.

[Here are a few questions from the Editor for Frank. Editor: How has the passenger ridership been at Kingston Station recently?]

Ridership of the train is good. At its peak, it was about 180,000 passengers a year, and prior to the pandemic was about 150,000 and increasing. The problem is that Amtrak does not employ enough Amtrak crew members to run full length trains, so some trains get sold out early. If Amtrak returned to using its normal ten-car train, the ridership numbers would likely improve.

[Editor: I heard that the Acela goes the fastest on the Northeast Corridor in the Great Swamp. Is that true?]

There are three stretches where the Acela is authorized to run up to its maximum authorized speed of 150 miles per hour: first (heading north from southern Rhode Island), the western part of the Great Swamp to a curve about three miles northeast of Kingston Station; second, past that curve into East Greenwich; and third, in a stretch of straight about thirteen miles long in Massachusetts from Attleboro through Mansfield. There are other stretches down in New Jersey where it can get up to about 140 mph or so. The Amtrak agent mentioned above, Jack McCabe, once got a ride in the cab of an Acela on a test run, going at a speed of 168 mph through Kingston.

[Editor: I once saw a man with a hat standing on the grass next to Kingston Station watch as the Acela rushed by. The rush of air took off his hat, which landed inside a fence surrounding a tree. The fence was high, so the man lost his hat.]

One would think that passengers should be banned from the platform when the Acela speeds through Kingston Station, but to my knowledge, there has only been one “incident” where an elderly lady, panicked by the noise, tripped and sprained her ankle. Contrary to popular opinion, the airflow pushes you away and does not suck you in as it passes.

Dr. Alexander and Donna McBurney waiting on the platform at Kingston Station for a train to arrive, 2017 (Robin McBurney)

[Editor: Can you give more details about the fire in 1988? What was its cause? How much damage was there?]

There is still some question about the cause of the 1988 fire. There are two main hypotheses. First, a cigarette igniting debris between the platform planks and the side of the station. Alternatively, an electrical short in one of the boxes on the outside of the station. I don’t believe it ever got a formal determination. In any case, it started on the outside of the building and then worked its way inside. The damage was tremendous. The then-waiting room and ticket office were completely burned out and a hole was burned through the roof. There is general consensus that the firemen from the West Kingstown Volunteer Fire Department saved the station by their quick response and professionally putting out the fire. Since both the waiting room and ticket office were unusable, a house trailer for many months served as a temporary ticket office.

[Editor: I understand that as part of the renovation of the Kingston Station that the platform was raised and moved 40 feet. Can you talk about why that was needed and how it was done?

The station had to be moved after the period of the first restoration in the ’70s primarily for three reasons. First, the platforms had to be widened to accommodate the catenary poles for the new Acelas. Second, as the Acelas would be going through the station area at full speed, the platforms had to be wider so people could stand back further. Third, the new platforms would be higher so people could walk directly from a platform to a car, instead of having to walk up steps in the car. Before all this, the platforms were at track level, and people going on a southbound train could just walk across the tracks. The result was that the station had to be moved both back and up to accommodate the higher platforms. After this was stopped, but before the overpass was built, southbound passengers had to take a bus from the station over the Route 138 overpass, through Arnold Lumber, to the platform on the other side. If you missed the bus, you missed your train.

[Editor: There appear to be a good number of parking spaces for such a small station, but the parking lots are full or close to it much of the time. Why is that?]

The lots have been built in stages, as funding has come in. The people who can legally park there are Amtrak passengers and users of the adjoining South County Bike Path (the former location of the short-line Narragansett Pier Railroad). Unfortunately, many URI students also use the lot, especially the one near the signal tower, because it’s much cheaper than buying a URI parking permit. One only need to view the lots during a summer weekday and a school year weekday to see the difference. Kingston is one of the few stations on the Northeast Corridor that doesn’t have paid parking. Another issue peculiar to Kingston is that passengers at other stations know that they’ll have to hunt for a parking space and so arrive early. Kingston passengers arrive five minutes before train time, panic, and double park, or park on the lawn, etc. This issue has been discussed for years by the Rhode Island Department of Transportation, which owns the lots, but there is still no resolution.

[Editor: Thank you Frank!]

You’re most welcome.

[Editor: On a related matter, I note that the archives in the South County History Center in Kingston contain two file boxes of documents (including newsletters) and photographs titled The Friends of Kingston Station.]