Providence and the rest of Rhode Island have an amazing history of impressive manufacturing companies. Of all the hundreds from the nineteenth century, I call five of them based in Providence the “Big Five.” They are Brown & Sharpe, The Corliss Steam Engine Company, Nicholson File Company, and American Screw Company. These companies employed thousands of Rhode Islanders at good paying jobs and made innovative products. Here are the stories of their founders.

Joseph R. Brown and Lucian Sharpe (Brown & Sharpe)

Joseph Brown and his protégée and successor Lucian Sharpe were the men who brought Rhode Island’s machine tool industry into national prominence and leadership. Born a generation earlier than Lucian (1810 to Lucian’s 1830), Joseph was the mechanical genius who founded the business and Lucian expanded it much like John Gorham did for his notable business enterprise as successor to his father Jabez.

Joseph was born in Warren, Rhode Island on January 26, 1810, the son of Patience Rogers of Newport and her husband, David Brown, a talented clock builder and dealer in clocks, watches, jewelry, and silverware. Joseph attended school until the then-ripe age of seventeen, but he also spent considerable time in his father’s shop learning and developing various mechanical skills. In 1827, after his family moved to Pawtucket, he secured a job in the machine shop of Wolcott and Harris in Valley Falls on the Blackstone River, two waterfalls above the Wilkinson Mill. Here Joseph engaged in the manufacture of cotton machinery and began to develop an interest in machine toolmaking.

After a brief debut in the machine-making business, he worked with his father in the construction of tower clocks for churches in the towns of Pawtucket, Taunton, and New Bedford. When Joseph became of age in 1831, he opened his own small shop and began the manufacture of tools for the clock industry, precision measuring devices, lathes, and a gauge for the brass industry. Then in 1833, he was joined by his father in a new venture when they acquired facilities at 60 South Main Street in Providence. From this inauspicious beginning would evolve a mammoth enterprise. In 1837, after four years of growth, this shop and its contents were destroyed by fire. With insurance proceeds of $2,000, Joseph and David moved their business across the street to 69 South Main. After 1841 Joseph became the sole proprietor when his restless father traveled west to Illinois in search of new opportunities.

As his business continued to develop, Joseph moved it to larger quarters on 115 South Main Street. At this location in 1848 he received Lucian Sharpe as an apprentice. This eighteen-year-old prospect, the son of stable owner Wilkes Sharpe and his wife Sally Chaffee, was Providence-born with family antecedents in Pomfret, Connecticut. Sharpe, who possessed a high-school education, impressed Brown not only with his mechanical aptitude but also with his drive, intelligence, literary proficiency, and organizational skills. On March 1, 1853, he became Brown’s partner under the firm name of J. R. Brown & Sharpe. This combination of technical and business talent thus united to make Brown & Sharpe a household name throughout Rhode Island and beyond.

When Sharpe became a partner, Brown’s business had been established for twenty years, earning a local reputation for producing excellent and accurate work, but earning only meager profits. Now Brown was free to give his undivided attention to his true genius–invention–while Sharpe could focus on increasing business, most notably via an 1858 contract with the Wilcox & Gibbs Sewing Machine Company to manufacture its entire product. Giving Brown & Sharpe a prominence in mechanical work, this key account was primarily responsible for firm’s decision to focus on the precision machine tool business, in which Brown excelled.

The litany of Joseph Brown’s mechanical inventions is amazing, especially to those, like historians, who generally possess little technical aptitude. Perhaps encouraged by his familiarity with clock mechanisms, Brown became interested in making precise measuring devices, the first of which was an automatic linear-dividing engine. By 1853 he had perfected the vernier caliper, the first practical tool for exact measurements that could be sold at a price affordable for the ordinary machinist. This technical breakthrough was followed by such patented inventions as a precision gear-cutting and dividing engine, a turret screw machine, the universal milling machine, the micrometer caliper, the universal grinding machine, and a series of other gauges and machine tool innovations that revolutionized the industry and made Brown & Sharpe the national leader in the production of such items.

Brown was a simple, unostentatious man consumed by his work, which was his greatest pleasure. According to one who knew him, he had no ambition to make a large amount of money or to establish a very large industry, but his inventions were of such a character that when made known they were at once appreciated and were of inestimable value to the business. Lucian Sharpe was the public relations and marketing genius who made them known internationally.

Brown married Caroline Niles in 1837, and the couple had two children before her death in 1851. In the following year he married Jane Mowry of Pawtucket. As his health began to fail, he devoted more time to leisure, and the pair toured Europe in 1866 and then made an extended stay in 1867. Brown died at his summer retreat at the Isles of Shoals, New Hampshire on July 3, 1876.

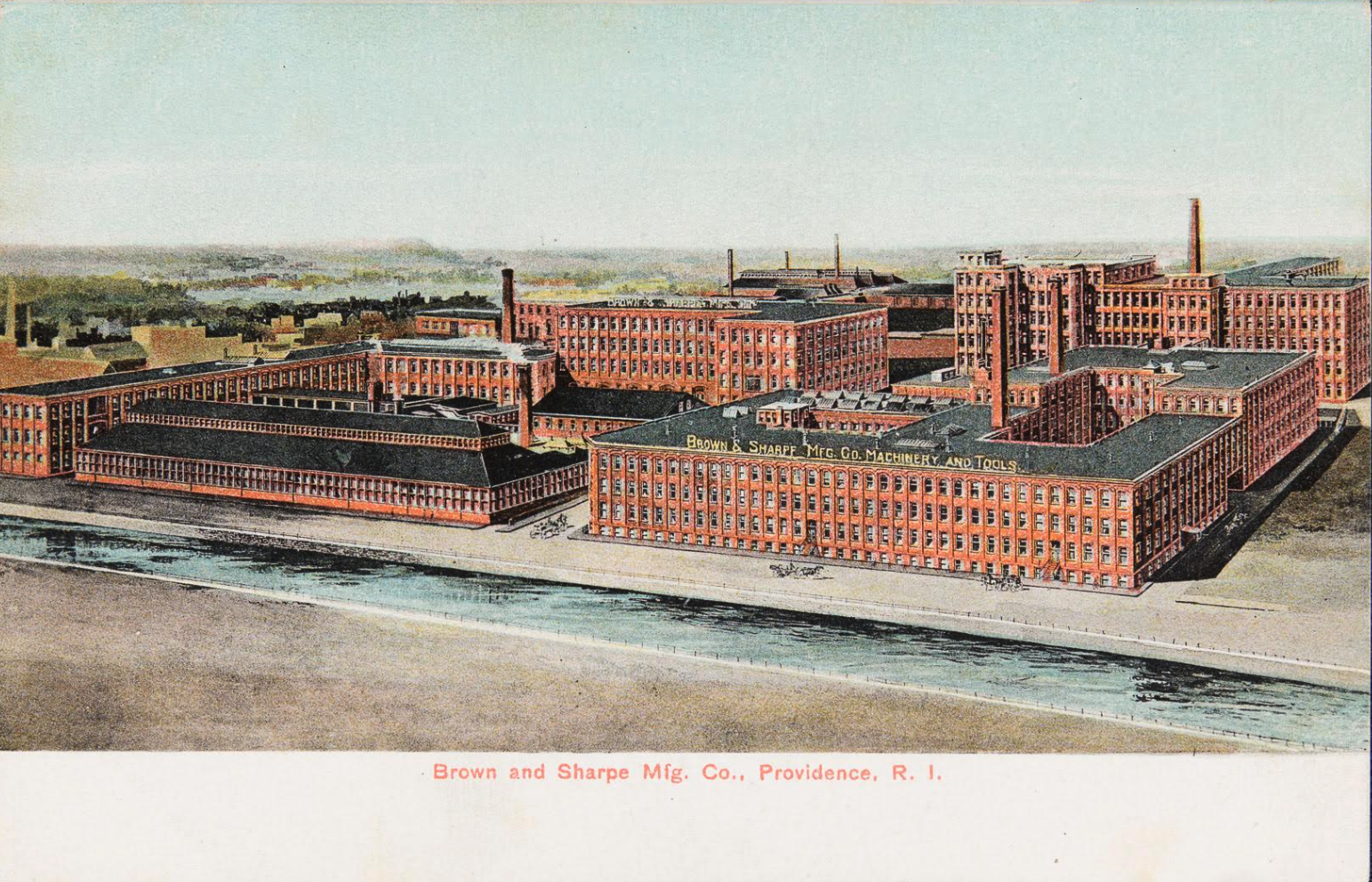

During the years before and after Brown’s death, Lucian Sharpe’s marketing ability and managerial skill made the company one of the world’s largest machine tool enterprises. In 1853 the floor space of its buildings covered 1,800 square feet; by 1899, the year of Sharpe’s death, that space had increased to 293,760 square feet in seventeen interrelated buildings. During that same period, the Brown & Sharpe workforce expanded from fewer than twenty employees to 2,000 craftsmen. Among those in that skilled work force were Hall of Fame inductees Frederick Grinnell, fire sprinkler inventor, William Nicholson, the file king, and Henry Leland, founder of the Cadillac and Lincoln Motor Companies. These and other craftsmen honed their skills at Brown & Sharpe.

Sharpe avoided active involvement in politics and took no part in the management of other manufacturing or commercial enterprises, except as director (from 1874) of the Wilcox & Gibbs Sewing Machine Company. However, he was a member of the board of directors of three Providence banks and the Providence Gas Company. Most important was his position as president of the Providence Journal Company from 1886 until his death.

Lucian Sharpe married Louisa Dexter on June 25, 1857, and the couple had four daughters, and two sons. His daughters married into the Chafee and Metcalf families and were prominent in the development of the Rhode Island School of Design and the funding of many local charitable agencies.

Unlike many entrepreneurs Sharpe never retired to rest on his laurels; he was intensely focused on his business and actively managed it until his death, which occurred on October 17, 1899, during his return voyage from Europe, where he had journeyed in hopes of regaining his health. He was sixty-nine years of age at his passing.

The business built by this duo continued through the twentieth century, at its peak operating eleven plants in four countries. In January 1965 it moved its main plant from Providence to a more modern facility in North Kingstown that it named Precision Park. Gradually however, labor problems, money problems, and the technological revolution debilitated the once-mighty creation of Joseph Brown and Lucian Sharpe. The end came in April 2001 when Henry Sharpe, Jr. yielded to the inevitable and sold its assets to Hexagon A. B., a metrology company based in Stockholm, Sweden.

Fortunately, this Rhode Island industrial giant has found an able chronicler. In 2017, historian Gerald M. Carbone, using the voluminous company papers carefully stored at the Rhode Island Historical Society, published Brown & Sharpe and the Measure of American Industry. As stated at the conclusion of my review of Carbone’s book: Providence’s five industrial wonders have evaporated along with the status of Providence as one of America’s manufacturing marvels. Progress often exacts a painful price. My wish is that the other four wonders obtain a writer with the talent and research skills of Carbone to preserve their memory for posterity.

George H. Corliss (Corliss Steam Engine Company)

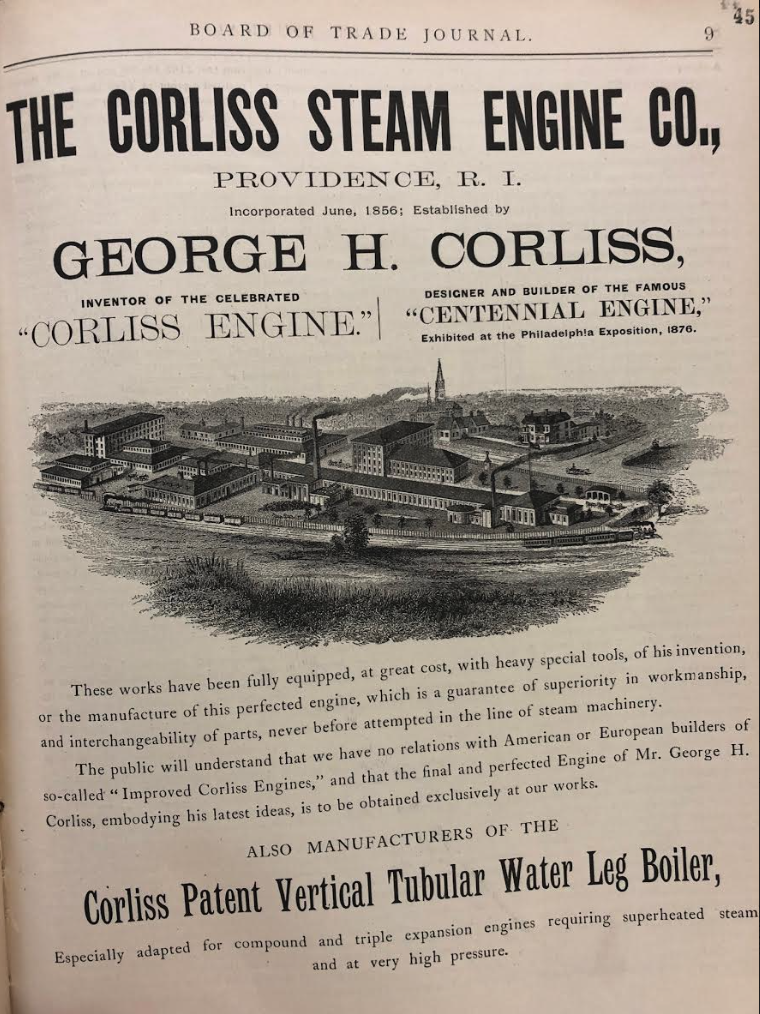

Of all Rhode Island’s successful entrepreneurs, manufacturers, and inventors, none achieved more fame and notoriety in their lifetime than George H. Corliss, the man whose refinements to the steam engine earned him international acclaim. Corliss’s crowning glory came in 1876 at the centennial celebration of the Declaration of Independence. He was invited to help plan a mammoth Philadelphia exhibition of American achievements. Its centerpiece was a 776-ton Corliss engine that was forty feet high, had a flywheel thirty feet in diameter, and weighed eleven tons. The wheel meshed with a pinion shaft that was 325 feet long and delivered power to the hundreds of machines that were on display in the exhibition’s thirteen-acre main hall. The Centennial Engine, as it was called, was built in Providence and shipped by train on seventy-one flat cars to Philadelphia.

I already wrote about George Corliss in a prior article on this website. You can read more about him here: http://smallstatebighistory.com/george-h-corliss/

John Gorham (Gorham Manufacturing Company)

John Gorham was the son and protégé of noted jeweler and silversmith Jabez Gorham, who, like John, is a Hall of Fame inductee. Jabez was an apprentice to silversmith Nehemiah Dodge, and with Dodge’s guidance, the elder Gorham learned the trade but chose not to emulate his mentor by crafting costume jewelry when he concluded his apprenticeship in 1813. Not long thereafter, Jabez entered into a partnership (as was quite common in this business) with other craftsmen and began the manufacture of gold jewelry on the second floor of a building at the corner of North Main and Steeple Street in Providence’s original jewelry district. In 1818, after five years of partnership operation, Gorham became the sole proprietor and soon won a regional reputation by making French filigree jewelry and a special kind of popular gold chain that became known as the Gorham chain.

From 1825 through 1840 Jabez took on a succession of three partners–Stanton Beebe, Henry Lamson Webster, and William Gladding Price–the last of whom married Jabez’s daughter Amanda. The Webster partnership, which opened a shop at 12 Steeple Street in 1831, made the momentous shift to selling silver spoons as its leading product. From that point onward, silverware and Gorham became synonymous. In 1837, Jabez took on an apprentice who would one day transform the Gorham Manufacturing Company into a world leader in the production of silverware, holloware, and statuary. That protégé was his third child, John, whose birth on November 18, 1820, caused complications that led to the death of Gorham’s first wife, Amey Thurber, eight days later at the age of twenty-five.

In 1839 Jabez withdrew from his partnership with Webster and Price but continued to manufacture his Gorham chain. Perhaps at the urging of his son John, he resumed the manufacture of spoons and silverware in 1841 at 12 Steeple Street by forming the firm of J. Gorham & Son.

Jabez retired permanently from the business in 1847, having achieved both fame and prosperity. In 1858 he and his second wife, the former Lydia Dexter, built an imposing brick house at the corner of Benefit and Bowden Streets, where Jabez continued to reside until his death on March 24, 1869, at the age of seventy-seven.

John Gorham proved to be a most worthy successor to Jabez. His father’s business model relied on a small number of craftsmen producing a limited number of quality items, but John quickly began to recognize the advantages of mechanization to augment hand craftsmanship in the production of silverware. His research into manufacturing processes brought him to the Springfield Arsenal in Massachusetts and the U.S. Mint in Philadelphia, where he learned procedures for handling enormous quantities of coin silver.

His entry into silver manufacturing was blessed by good timing. In 1842 those engaged in the production of silverware successfully petitioned Congress to impose a 30 percent ad valorem tax on imported silver, a levy that gave American manufacturers a major impetus to increase production. After John bought out his father’s interest in 1847, his incessant drive to learn more about his competitors and their business practices brought him to Europe in 1852, where he visited English factories in Birmingham and Sheffield, the London Mint, and the Woolwich Arsenal, as well as silver shops in Brussels and Paris. Upon his return to Providence, Gorham quickly introduced factory methods to augment hand craftsmanship, installed a steam engine to power his new machinery, and even designed new machinery himself. By 1869 he had made four fact-finding trips to Europe.

In 1850 Gorham admitted his nephew Gorham Thurber as a partner, and another relative, Lewis Dexter, assumed a partnership position with the company in 1852. In addition to management adjustment, Gorham also realized that he could no longer rely on the traditional seven-year apprentice system to enlarge his skilled workforce which numbered only twelve in 1850. During the 1850s he set out to recruit more than one hundred skilled craftsmen from overseas. By 1861 Gorham had increased his workforce to 150, and by the end of the Civil War he had 312 employees. Contemporaries described him as a practical mechanic of artistic taste, with an unusual ability to organize and construct.

In 1863 the Rhode Island legislature chartered John’s firm as the Gorham Manufacturing Company, and he assumed its presidency, with Gorham Thurber designated the treasurer. Within a decade Gorham was reputed to be the largest manufacturer of coin silverware in the world, with a workforce that had grown to 450 employees toiling in buildings that occupied an entire block around Steeple and North Main Streets.

John Gorham had taken many financial risks in expanding his father’s company, so when the Panic of 1873 hit, he, like the Spragues, was forced into bankruptcy. The economic impact on John personally left him merely a Gorham Company employee when the firm recovered, so he resigned from the company in 1878. One contemporary observer noted that he is in no business and has no means.

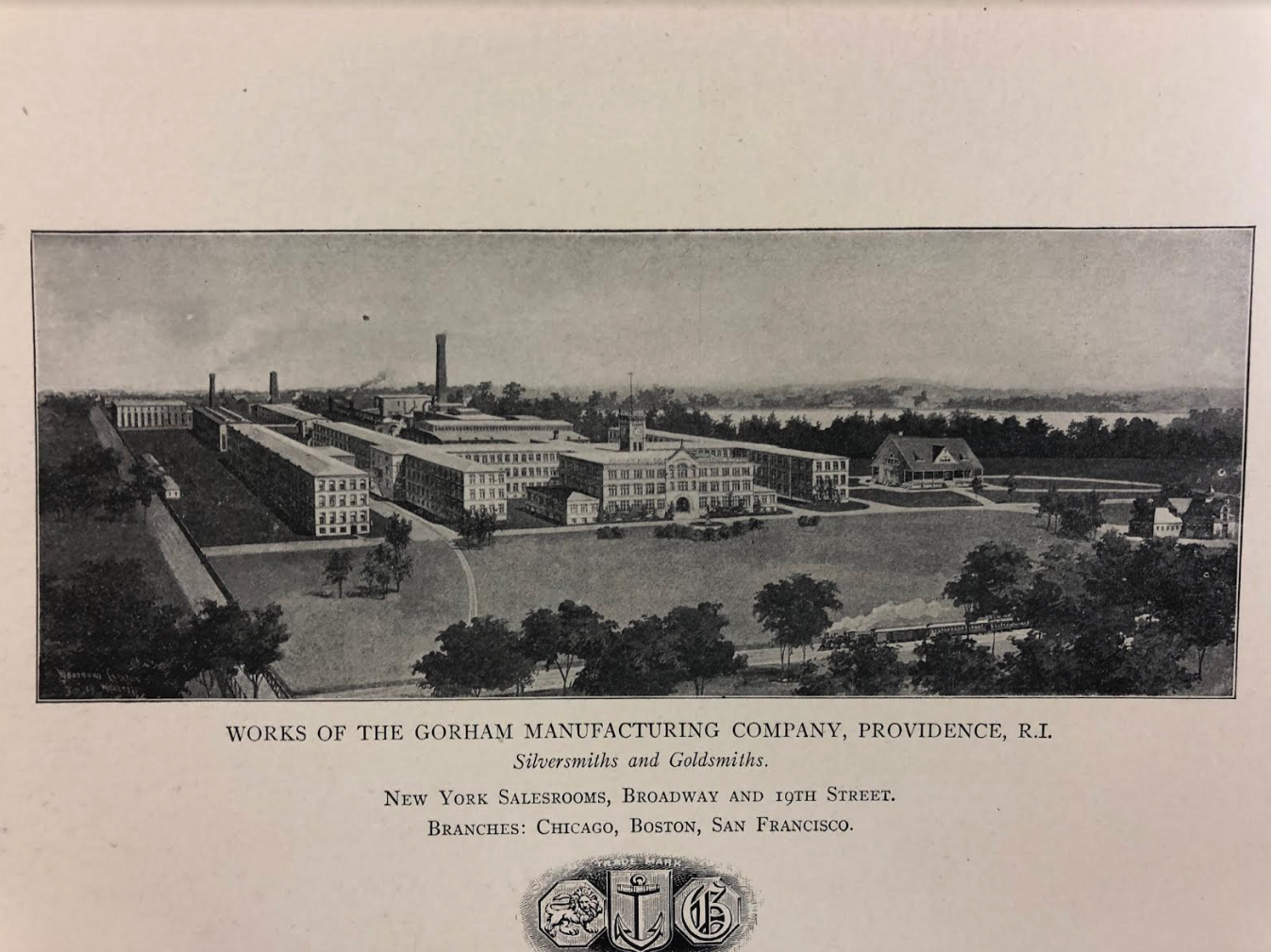

Sometime after 1881 John moved permanently to Chase City, Virginia, where he died on June 26, 1898. Despite this personal setback near the end of his career, his entrepreneurial spirit, his inventiveness, and his management expertise had taken a small business founded by his father and grown it to be one of America’s great industrial wonders. Although John Gorham himself had died, his creation thrived in its new and expansive complex at the end of Adelaide Avenue in the Elmwood section of Providence, to which it relocated in 1890.

Outside of his business ventures, John’s personal life was relatively uneventful. In the 1840s he attained the rank of lieutenant colonel in a militia unit called the Providence Horse Guards, and he served one year as a Whig state legislator. In 1848 he married Amey Thurber, a woman with the same name as his mother. The couple had six children, three of whom died before their father’s move to Virginia.

In 1967 Gorham became a division of the Rhode Island conglomerate Textron, which then sold it to Dansk in 1989. After two more flips it now operates as a division of Lenox Corporation.

When the Elmwood plant closed in 1985, that event marked the removal from the city of the last of its five industrial wonders of the world. A much smaller Gorham manufacturing plant was built in Smithfield in 1985 but that closed its doors in 2001.

In Rhode Island, however, the Gorham name lives on, and its most famous creation, the statue of the Independent Man atop Rhode Island’s State House, crafted a year after John’s death, will long be a visible reminder of the world-renowned business that Jabez and John Gorham began and nurtured. The voluminous records of their iconic company are now stored at Brown University’s John Hay Library. Gorham silverware can also be seen in many museums nationwide, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City and Providence’s Rhode Island School of Design Museum.

William Gorham Angell (American Screw Company)

William Gorham Angell was born in Providence on November 21, 1811. He was a descendant of Thomas Angell, one of Providence’s first settlers. Despite his lineage, William’s family was one of modest means: his father, Enos, was a carpenter and his mother, Catherine Gorham, one of ten children, was the sister of the soon-to-be famous Rhode Island silversmith Jabez Gorham. Acquiring only a basic common-school education, William Angell assumed his father’s trade as a carpenter until he was about twenty years of age. Then he entered into a partnership with his uncle John Gorham, making reeds to allow looms to operate more efficiently. However, Angell possessed what his associates described as an intuitive perception of the capabilities of a machine, and during these years he experimented with machinery for making iron screws to be used in woodworking.

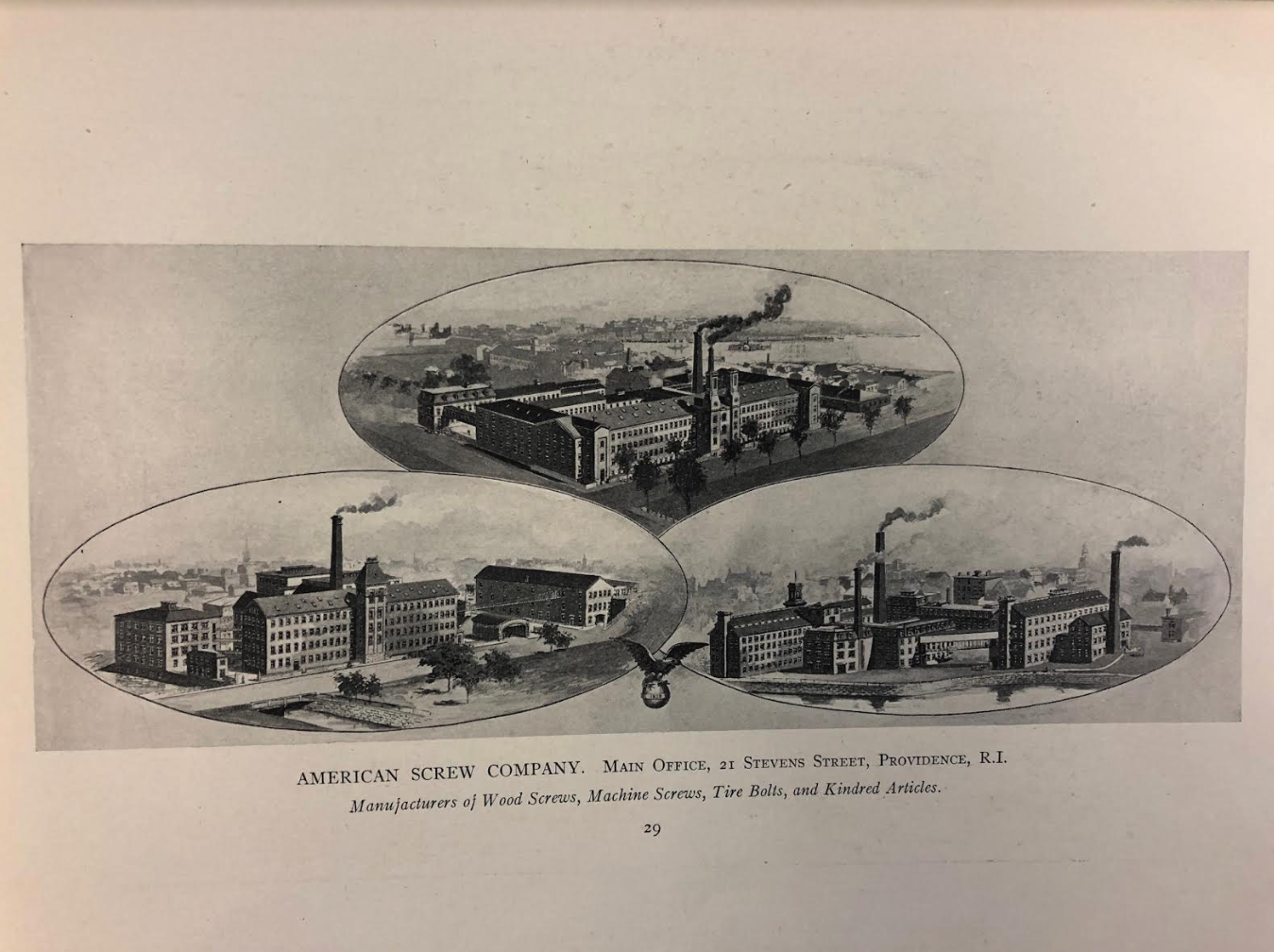

Angell devised several improvements in the screw-making machinery of his era, and when several Providence investors formed the Eagle Screw Company in 1838 to compete with the English manufacturers of these fasteners, Angell became its agent and manager. After more than twenty successful but challenging years in business, Eagle united with the New England Company in 1860 to form the American Screw Company, with Angell as its president.

Initially capitalized at one million dollars, the firm soon ranked as the world’s largest producer of wood and machine screws. It was regarded by century’s end as one of Providence’s five industrial wonders of the world.

By 1860, according to one source, Angell’s long experience and mechanical skill gave him an intimate and practical acquaintance and familiarity with the entire history of the manufacture of screws and with the principle, construction, and operation of every machine used in this country or Europe for making screws. Along with his inventive ability, Angell had business sagacity and remarkable skill as an administrator. He knew intimately every aspect of his company, and he was, in addition, an excellent draftsman and a skilled architect and builder. These talents were used in the construction of factories that could stand the strain of the heavy machinery necessary in his manufacturing process.

By 1900 American Screw operated three major mill complexes within the city: the Bay State Mill and the Eagle Mill, on the north and south sides of Stevens Street near Randall (now Moshassuck) Square, and the New England Mill, on Eddy Street near the junction with Allens Avenue. The company remained one of Providence’s leading employers until 1949, when it moved to Willimantic, Connecticut.

Angell concentrated on his business to the exclusion of most other pursuits, but he contributed liberally, though inconspicuously, toward the relief of the poor and unfortunate.

Friends commented that he was so much engrossed with his special business that he had little or no time for anything else, be it politics, social life, or amusements. It was an axiom with Angell that a man could do but one thing well.

Angell married Ann R. Stewart in January 1836 and became the father or two sons, Edwin Gorham and William Henry. The former succeeded him as president and executive manager of the American Screw Company after William Angell’s death from consumption at his home on 30 Benefit Street, Providence on May 13, 1870, at the age of fifty-eight. He is buried in Providence’s North Burying Ground.

Edwin Angell presided over the business until his death on December 15, 1903. At that time, Samuel Mowry Nicholson, son of William, took over the presidency and management of the American Screw Company, thereby uniting two of Providence’s industrial wonders of the late nineteenth century.

William Thomas Nicholson (Nicholson File Company)

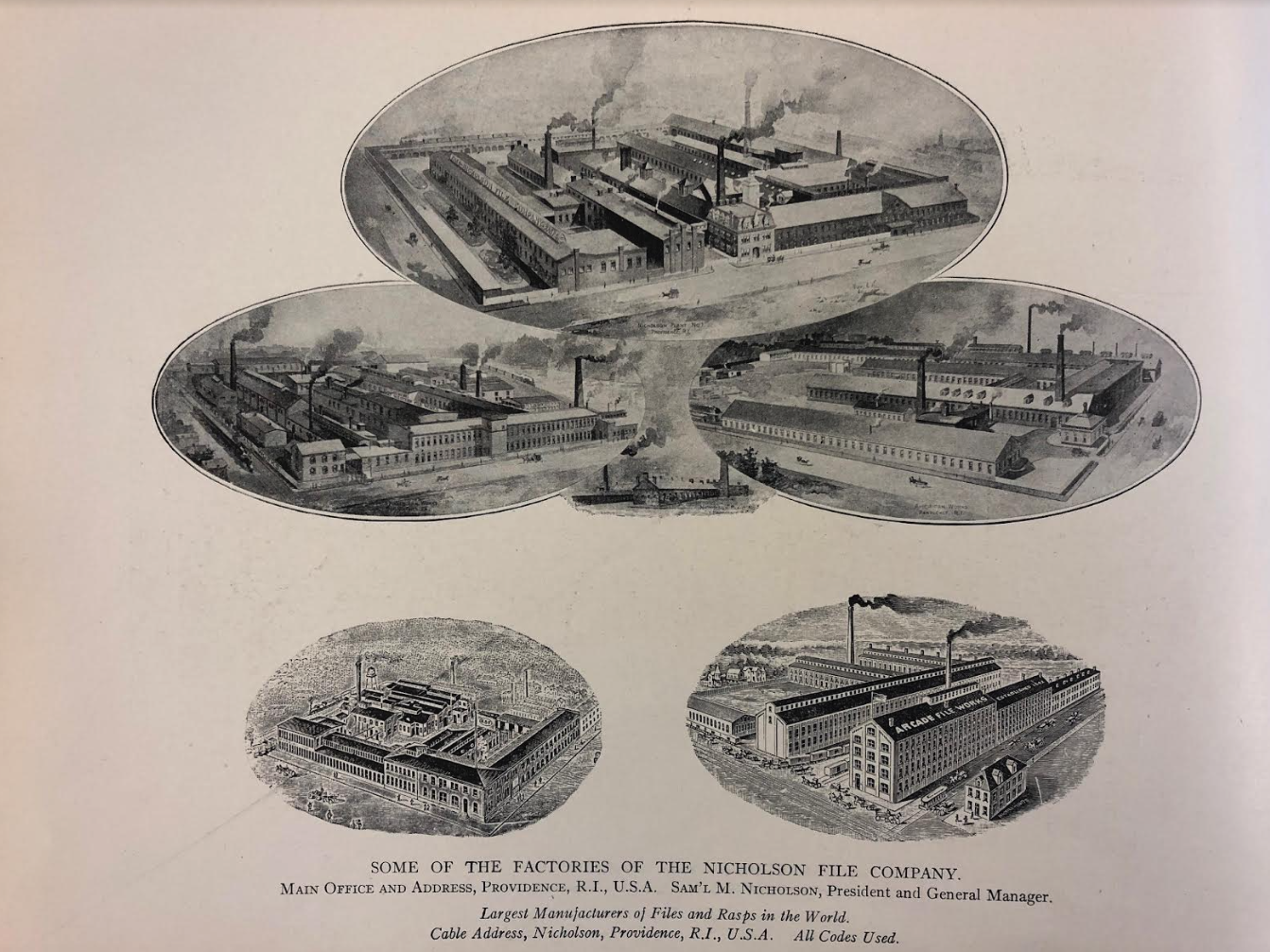

William T. Nicholson was the founder of the Nicholson File Company of Providence, the originator of machine-made files and rasps in America, the largest company of its kind in the world, and one of Providence’s five industrial wonders of the nineteenth century.

Nicholson was born on March 22, 1834, in the village of Pawtucket, then in the town of North Providence, to Eliza Forrestell and William Nicholson. His father, a machinist, moved the family to Whitinsville, Massachusetts where young William was raised and educated in the schools of that town and at the nearby Uxbridge Academy. At age fourteen, he became an apprentice machinist in Whitinsville, but moved to Providence when seventeen to seek better job opportunities. He found them at Brown & Sharpe Manufacturing Company where, rising to the position of shop manager by 1856, he supervised the production of that firm’s precision instruments.

In 1857 Nicholson married Elizabeth Dexter Gardiner who was descended from an old-line Rhode Island family. The couple had five children–Stephen, Samuel, William, Eva, and Elizabeth.

In 1858 Nicholson opened his own machine company in partnership with Isaac Brownell. By 1860, he had bought Brownell out and moved to a larger facility. After the outbreak of the Civil War, he had formed a partnership (Nicholson & Company) with Henry A. Monroe to supply the Union Army with Springfield Rifles. Then he turned his full attention to producing machine-cut files. In 1864, after patenting his invention, he formed the Nicholson File Company. Eventually this enterprise became world-renowned for the quality of its specialized product and brought Nicholson and his family great wealth.

In his later years Nicholson traveled widely and supported a number of civic projects, including the establishment of the Providence Public Library in 1877. He was for a time a member of the Board of Aldermen, the upper chamber of the Providence City Council.

William Nicholson died suddenly on October 17, 1893, and was succeeded by his son and protégée Samuel Mowry Nicholson who continued the firm’s expansion and became a leading industrialist in his own right, as did his son and successor Paul C. Nicholson, Sr.

By 1900 the company’s six plants–in Providence, in Pawtucket, and four out-of-state–employed nearly 2,500 workers and produced over 10,000 files and rasps a day, an output well beyond its founder’s initial daily goal of 300. In 1903, Samuel Nicholson also acquired the huge American Screw Company after the death of Edwin Angell, son of its founder.

Nicholson File continued to operate under the direction of the Nicholson family until 1969. Its complex on Acorn Street in Providence consisting of twenty-four buildings occupying seven acres was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2005. The family’s summer estate at Wind Hill on Bristol Point was sold by Paul C. Nicholson Jr. to nearby Roger Williams University in late 2017 for nearly $7 million. The Rhode Island Historical Society maintains a collection of the company’s records including its patents.

Nicholson File began to phase out its Providence operations in 1952 and relocate to Anderson, Indiana, the site of a subsidiary plant that it had acquired early in the century. The company remained in Anderson until the late 1970s when recurrent labor disputes prompted it to relocate to Cullman, Alabama. In 2011 it was acquired by Cooper Industries but remains in Cullman as the Nicholson Division of Cooper Industries.

[Each mini-biography originally appeared as a chapter in The Leaders of Rhode Island’s Golden Age by Dr. Patrick T. Conley (History Press, 2019)]