Pleasure the means, the end virtue.[1]

The theater in Providence has a long and rich history. Fledging attempts to establish a theatre in Providence go back to the late eighteenth century; but by the mid-nineteenth century the theatre was well established. The article that follows recounts some of the theaters that flourished in the early years. Part II, to be released next week, will address the modern era of the theatre in the capital city and may still be remembered by some of our senior readers.

Some Early Theaters

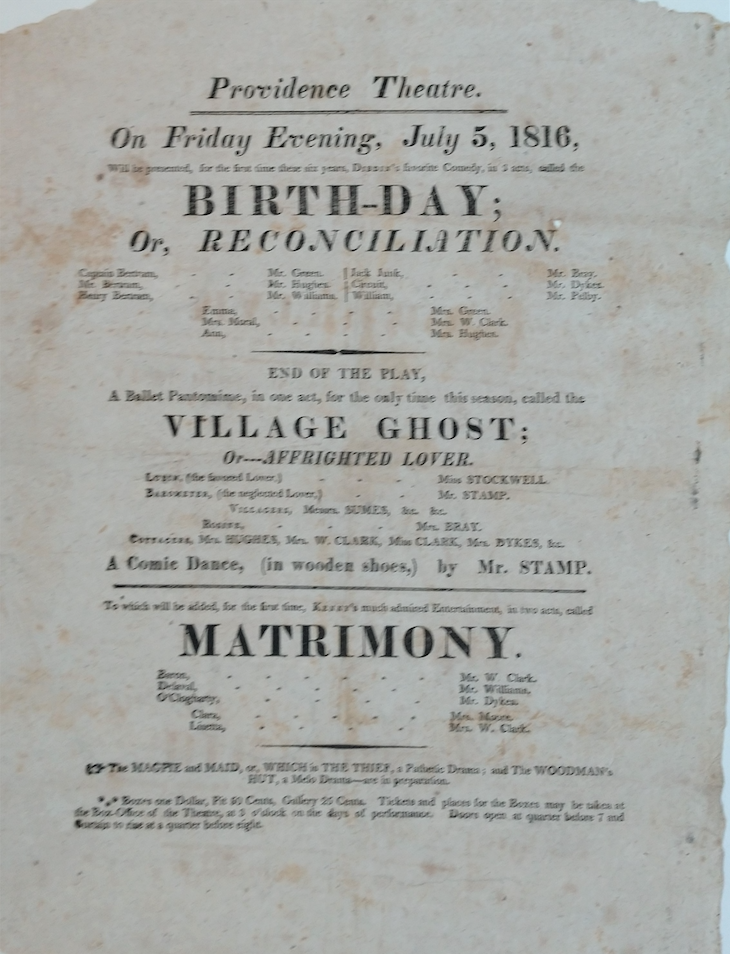

Providence was not always home to a theater. For much of the eighteenth century the Puritan ethic that held sway in New England since its founding took great exception to frivolous activities and attending a theatrical performance was at the top of the list of such activities. While occasional theatrical troupes visited Providence as early as 1761, it was not until 1794 that a theater opened. Still, there was much resistance in the community to it and many ministers offered sermons from their pulpits decrying the theater as the path to licentiousness. Regardless, the Providence Theater opened temporarily at the back of a local coffeehouse in Market Square until a permanent theater could be built at the corner of Westminster and Mathewson streets. This theater lasted a good number of years. Paradoxically, in 1832, the theater was sold for the purpose of building a church—Grace Church now occupies that plot of land

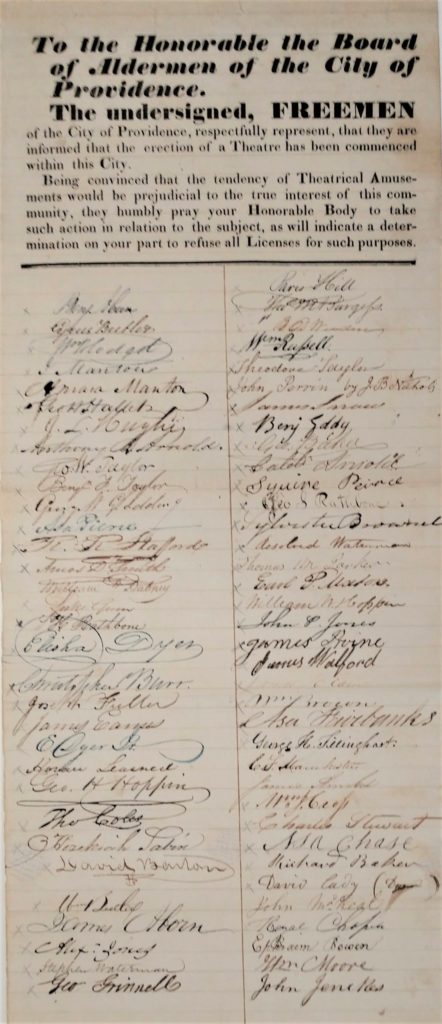

For several years thereafter there were no theaters in Providence, but in 1838 a new theater began construction on Dorrance Street between Pine and Friendship streets. Even then there were some residents of the city who tried to persuade the city’s leaders to deny the new theater a license. Clearly, the old Puritan ethic was still evident in 1838. The theater, named Shakespeare Hall, did receive a license. Soon there were other theaters in operation in Providence and the city would never again to be without one.

While Providence in the nineteenth century had a number of theaters, four are of particular significance. Of course, none of these theaters showed movies, rather they offered theatrical performances, plays, opera (grand and comic), musicals, and some offered vaudeville acts.

The first of these significant theaters was the Academy of Music located in the Phenix Building. The site and name of the building are appropriate as the Phenix Building was built on the ashes of the burned-out Forbes Theater on Westminster Street. The Forbes was managed by William C. Forbes who maintained the theater from 1849 until it burned down on November 15, 1858. The Academy of Music was situated on the second floor of the building, with a gallery (balcony) on the third floor. Soon after the new building was completed the theater opened for its first performance.

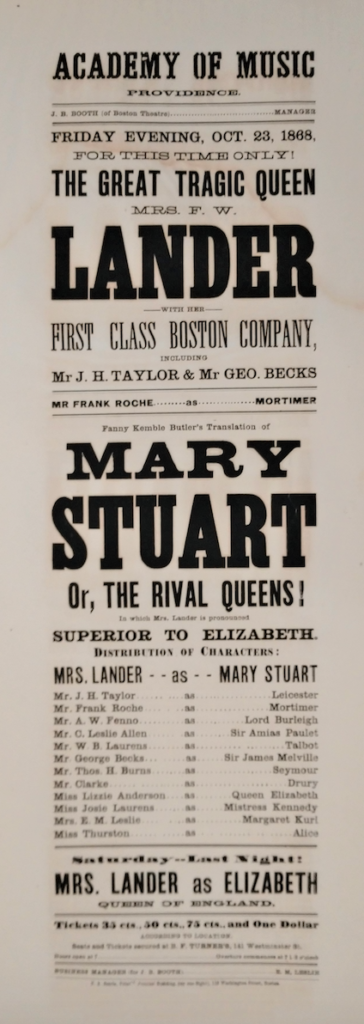

The Academy of Music became one of the principal theaters of Providence for the next twenty years. Among its noted performers was the future presidential assassin, John Wilkes Booth, who appeared on October 16, 1863, in Shakespeare’s Richard III. Prophetically the Academy of Music’s ad in that day’s issue of the Providence Journal read in part, “We must be brief when traitors brave the field.” The theater was often on shaky ground due to managerial and financial problems. For a while in 1873 it closed due to a fire in the building. It did reopen but, in late 1878, if offered its final performances before closing for good.

An 1868 Academy of Music playbill highlighting the famous British actress Fanny Kemble in the play Mary Stuart (Author’s collection)

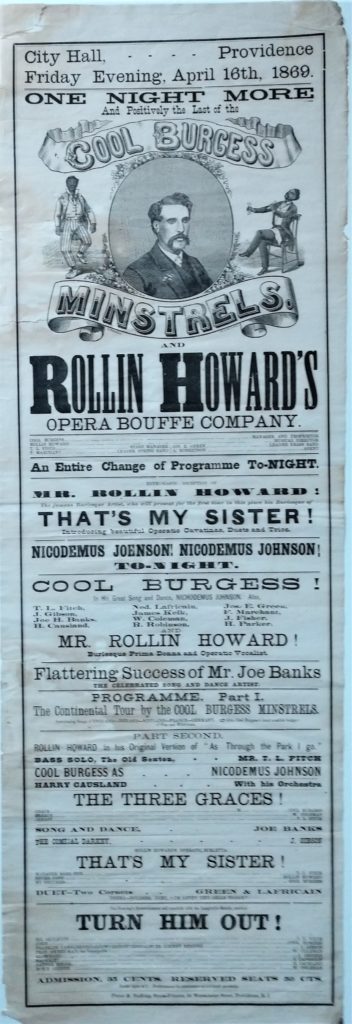

Less than two years after the opening of the Academy of Music, the City Hall Theater, later renamed Harrington’s Opera House, was built on land leased from the city. The land was commonly referred to as the City Hall Lot and today it is the location of Providence’s City Hall. This theater’s inaugural performance occurred on January 4, 1865, with a concert by the American Brass Band. A newspaper ad announcing the program noted, “Previous to the Concert, Mayor Doyle will make a short address, dedicating the Hall to the public.”[2] The theater was used for a variety of programs, concerts, minstrel shows, dramatic performances and lectures. Notably, Charles Dickens, the famous English author, appeared on two consecutive nights before a packed house, February 20 and 21, 1868, reading excerpts from his works, including the chapter entitled The Trial from The Pickwick Papers, A Christmas Carol, and other favorites. Following its last performance on August 1, 1874, the theater was razed to make way for the still-in-use Providence City Hall.

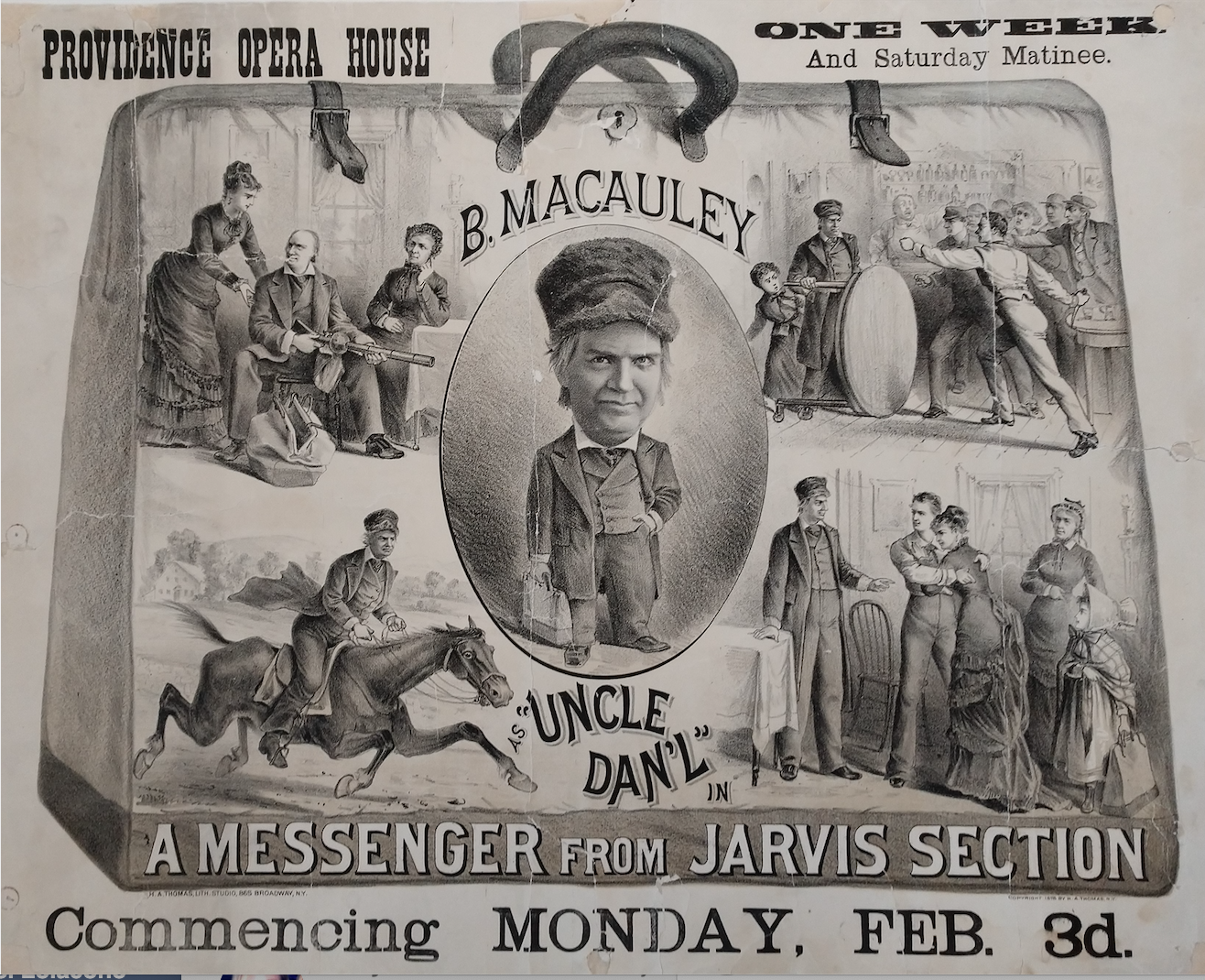

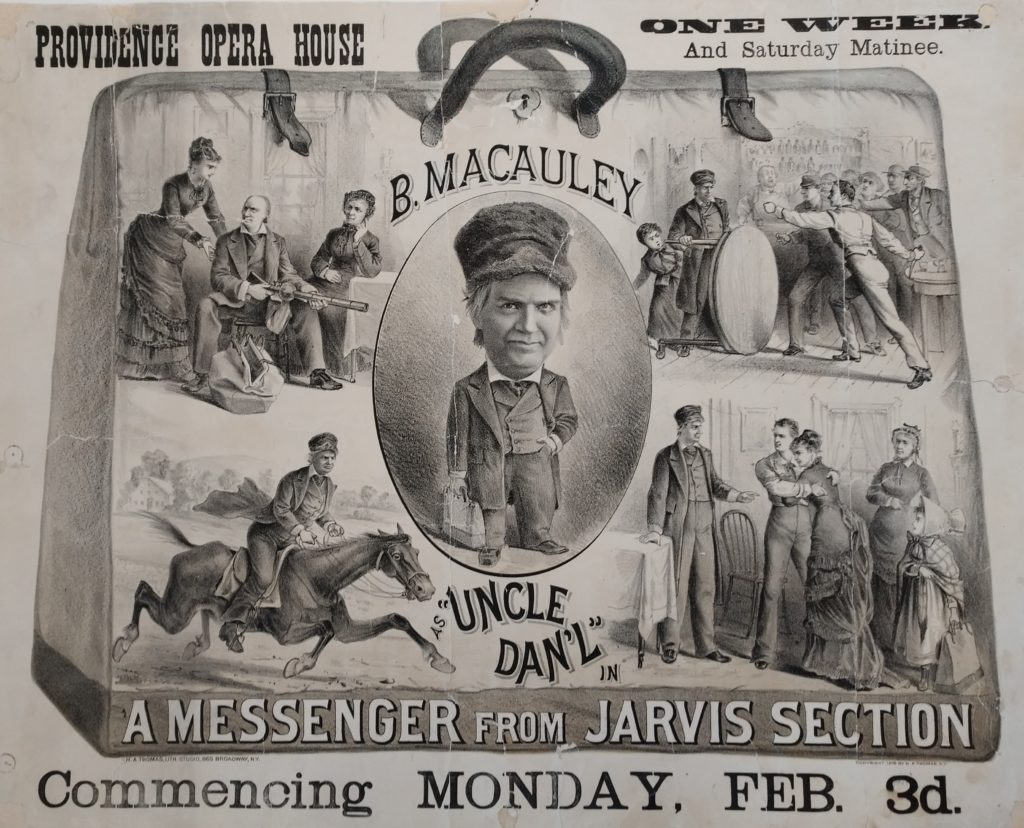

The most significant theater to operate in the city during the nineteenth century was the Providence Opera House. Located on Dorrance Street between Pine and Eddy streets, it opened on December 4, 1871, with lots of fanfare including longwinded speeches by Mayor Doyle and other city dignitaries.[3] From its opening until its final curtain call in March 1931, the Opera House played host for sixty years to some of the city’s most significant theatrical performances.

A lithograph poster advertising the February 1879 performance of A Messenger from Jarvis Section staring Barney Macauley at the Providence Opera House (Author’s collection)

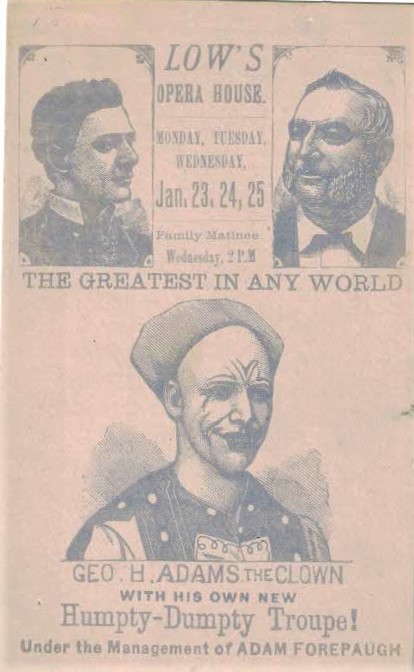

Low’s Opera House was the last of the four theaters discussed here to open. It was initially built as a public hall at Westminster and Union streets in 1887. In the following year it was remodeled into a theater, opening on March 4, 1878 (the same year that the Academy of Music closed). It was developed as a theater by William H. Low, Jr., a 28-year-old Brown University graduate who had no prior experience running a theater. The theater’s name changed to B. F. Keith’s Gaiety Opera House in 1889 when Low sold it to Benjamin Franklin Keith. The name changed again to Keith’s New Theater in 1912 and following World War I, no doubt propelled by a surge of patriotism, the name changed to Victory Theater. Finally, in 1935 it became the Empire. In 1949 the theater was razed and replaced with a W.T. Grant department store. In its heyday the theater saw notable performances by the leading actors and actresses of the age including the great tragedian Edwin Booth (brother of John Wilkes Booth and a much superior actor) and French star Sarah Bernhardt in her first American tour. Bernhardt, known as The Divine Sarah, appeared as Marguerite Gautier in Alexandre Dumas’s play Camille on the evening of April 6, 1881. This theater has the distinction of serving the city’s theater-going public for more than seventy years, more than any other theater up to this time.

An advertising card from 1882 for George H. Adams performance with his Humpty-Dumpty troupe at Low’s Opera House (Author’s collection)

Of course, other theaters populated the city during the early years, including the Theatre Comique, which burned to the ground in a dramatic (pun intended) fire in February 1888. Another theater, the Columbia, was a showboat built on a barge that was tied up to a dock on the Providence River at the Crawford Street bridge. Competing with these theaters were other indoor venues including Howard Hall, Infantry Hall, and Music Hall, to name but a few.

Outdoor Theaters

The year 1878 was remarkable not only for the closing of the Academy of Music and the opening of Low’s but also for the fact that two rival outdoor summer concert venues opened within city limits, just a week apart. Both outdoor venues were developed by rival band conductors.

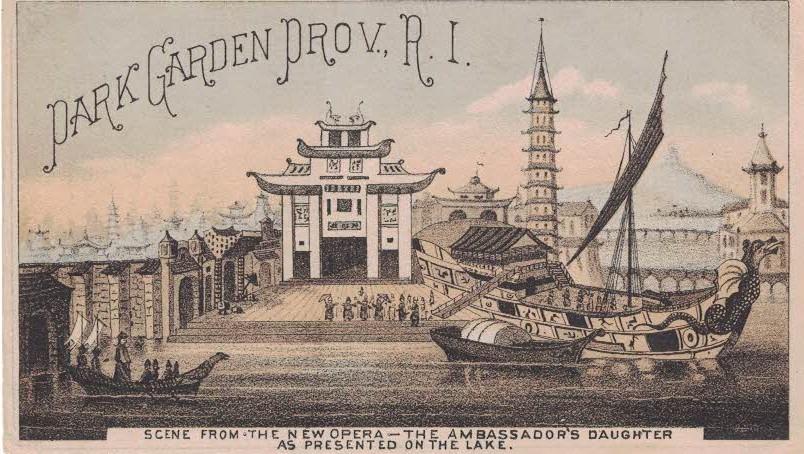

The first to open was Park Garden on Broad Street. A fund-raising opening was held on June 24 and a general public grand opening occurred the following day. The event on the 24th was billed as the Feast of Lanterns, and as one Providence newspaper noted it was attended by “crowds and crowds of people.” Park Garden was developed by David W. Reeves and John Shirley. Given that Reeves served as the conductor of the celebrated American Band, it should not be surprising that band concerts were offered nightly in the summer.[4] Patrons were greeted with beautiful flower gardens, shady walks, a two-acre “Fairy Lake,” an oak grove and walkways, a Robinson Crusoe hut and, as a precursor to today’s Water Fire, a Venetian gondola. Adjacent to the lake was an amphitheater in which the musical performances were held.

Perhaps Park Garden’s most notable performance occurred in 1879 when it presented Gilbert and Sullivan’s lyric opera H.M.S. Pinafore.[5] George Willard in his history of the Providence stage noted it was “the most realistic production ever given in this country of Gilbert and Sullivan’s celebrated opera . . . .” The price of admission was twenty-five cents and horse-cars marked “Park Garden” left from Market Square for the short ride to the gardens. Park Garden was short lived, lasting only six seasons. It closed after its 1883 season when its lease expired.

An 1880 advertising trade card for Park Garden’s performance of the opera The

Ambassador’s Daughter. (Author’s collection)

The other outdoor theatre was San Souci Gardens, located on Broadway at Jackson Street. Today this intersection has been lost due to the interstate highway that runs through the area. The grand opening was on July 1, 1883. Developed to feature the National Band conducted by William White, the garden also offered seating for 1,100 patrons for its performances of light operas and comedies. Within its first week of opening, entertainment acts included the Associated Artist Minstrel Troupe featuring “the only original American amusement Negro Minstrelsy.” Admission appears to have been a bargain, as it was less costly to go to San Souci Garden than Park Garden. Tickets cost only fifteen cents or two for twenty-five cents. Ten years after its opening Sans Souci Garden featured Providence resident, Sissieretta Jones, a young black opera singer who was beginning her successful international singing career. While the garden was located within a short walking distance from the center of the city, it could also be reached by horse-cars marked Broadway or Mount Pleasant. San Souci closed for good after its 1891 summer season.

Summer theater was gone from Providence, but the concept reappeared in the twentieth century at Warwick Musical Theater (1955 – 1999) and continues on at Matunuck’s Theater-by-the-Sea—but both venues hosted performances in enclosed settings. A true outdoor theater setting can still be experienced at Westerly’s Colonial Theater performances of Shakespeare-in-the-Park every summer at the Westerly Public Library’s delightful Wilcox Park.

Theater Companies

Performances in the early years of the Providence stage were usually traveling shows, in one week and gone the next. However, the concept of resident stock companies to augment the needs of the traveling cast first appeared in the mid-nineteenth century and continued well into the new century. The work must have been demanding for the stock players. George Willard in his book History of the Providence Stage noted, when discussing the Providence Opera House stock company’s third season, “They were frequently obliged to study a new play for every night in the week, as they supported all the dramatic stars who came that season . . . .” Some of the theater stock companies had resident professionals but occasionally there were stock companies comprised of all out-of-towners.

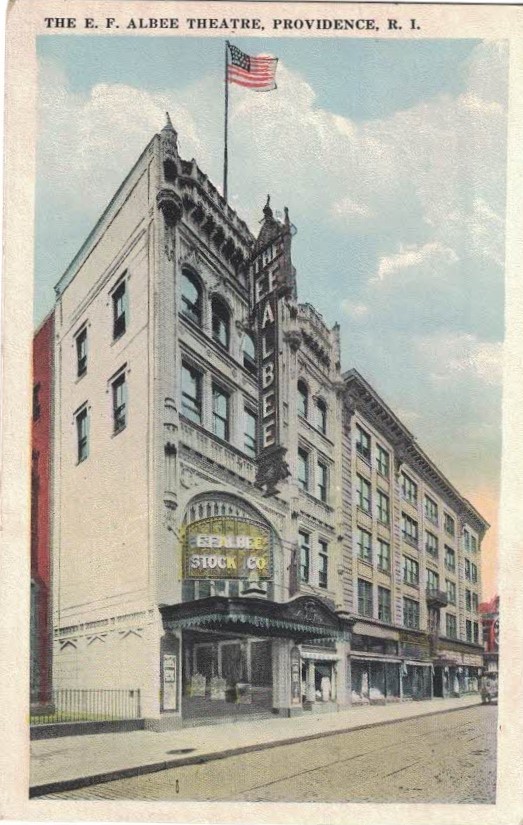

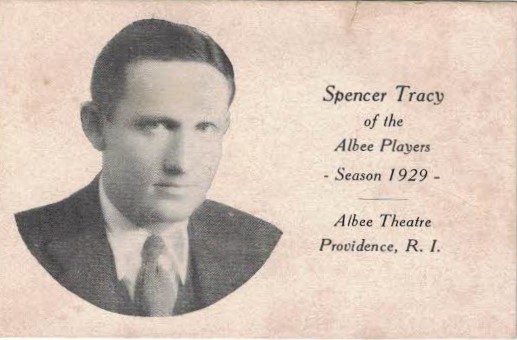

One of the more notable stock companies was the E. F. Albee Stock Company. Early in the twentieth century, Johnson Briscoe, then a noted critic of the stage, wrote, “The remarkable record of the Albee Stock Company, has carried wide-spread interest, not alone through Rhode Island and its environs, but the country at large, for no other city of its size can boast of an organization of the caliber of the Albee Company.” He went on to say, “Having made a close study of the modern stock company system, I think I can safely say that the Albee company stands among the three foremost organizations in the country to-day . . . .” Briscoe wrote these words of high praise for the preface to a short history of the Albee Stock Company on the celebration of its eleventh year. The stock company, founded in 1901, carried on until it disbanded after its 1929 season.[6] A long list of actors and actresses made up the company’s alumni but probably its most famous member was Spencer Tracy, who would move on to a legendary career in Hollywood movies, winning two Academy Awards.

A postcard view of the Albee theater from around the time it first opened in 1919 and a souvenir card showing Albee Stock Company member Spencer Tracy from a deck of twenty cards issued by the Outlet Company in 1929 (Author’s collection)

Amateur theater companies also existed. In 1887 one group of amateur actors formed the Amateur Dramatic Club and gave performances at the aptly named Amateur Dramatic Hall located on the corner of South Main and Power streets. This hall was a converted Methodist church. In time the hall’s name was changed to the Talma Theater, the home of the thespian group named the Talma Club.

It was at this location, in December 1909, that the first performance of another amateur group called The Players occurred in The Liars by Henry Arthur Jones. In time The Players would move to Infantry Hall, one of several locations before finally settling into a permanent home in 1932. Today, after one hundred and twelve years The Players are still going strong, performing at the Barker Playhouse on Benefit Street.

Over time other theatrical companies have come and gone. One group with significant longevity is the Sock and Buskin of Brown University’s Dramatic Society. This collegiate theatrical group gave its first performance in 1901 and it continues to perform to this day.

Stock or repertory companies are evident even today as demonstrated by Providence’s renowned Trinity Repertory Company (founded in 1963) now in its 58th season. It too had its beginnings in a church building, located at the Trinity Square Playhouse adjacent to Trinity United Methodist Church located on Broad Street. This small playhouse provided the audience with a sense of intimacy with the actors, a feeling that was to be somewhat replicated in the downstairs theater at the Lederer at 201 Washington Street in downtown Providence. Like the Albee Stock Company, Trinity Rep, as it was known, has produced many actors and actresses that have gone on to national recognition. One of them is Richard Jenkins, who started his career at Trinity Rep, appeared in his first film in 1974, and later served as its artistic director from 1990 to 1994 (he is still acting today). Unlike the Albee Stock Company, Trinity Rep has entered into a collaborative initiative with Brown University offering upcoming actors, playwrights and directors an opportunity to work with a professional regional theater while earning an M.F.A.

Conclusion

For the last 225 years, except for several years in the 1830s, there have been theaters in Providence providing enlightenment, entertainment, and enjoyment to the city’s residents. The performances offered during this span of time have evolved to meet the taste of their audiences. So too have the theaters evolved from mainly live performance to mainly film. While most theaters from the past are now long gone, there are still a few that remain. Anyone attending the Lederer or Providence Performing Arts Center (PPAC) today can still get a sense of what the theater goers of the past experienced. The grandeur and excitement was palpable. No modern-day multiplex or home theater system can offer that feeling.

Selected Reading

Over the years there have been many articles and a few books written about the theaters of Providence. Several of them stand out. The first book was An Historical Account of the Providence Stage written by Charles Blake and published in 1868 in an edition of only 200 copies published by Providence bookseller George H. Whitney. Blake’s account, albeit in a much shorter version, had been first presented in a paper read at the Rhode Island Historical Society eight years earlier. The next book to appear on the subject occurred twenty-three years later when George O. Willard published History of the Providence Stage, 1762 – 1891. Willard’s book incorporated all of Blake’s book and essentially carried the history from where Blake left off in 1860 and carried it forward to 1891.

The next publication of note was an article that appeared in the Providence Magazine in October 1916. “Popular Amusements – The Drama in Providence” was a fifteen-page account of the theaters of the capitol city. What differentiates this article from both the Blake and Willard books is that it focused less on the performances and the actors and more on the theaters themselves. Numerous pictures of the theaters were displayed. Also much had changed since the printing of Willard’s book in 1891 and the appearance of the magazine article in 1916—drama now shared the stage with vaudeville and some theaters like the Modern on Westminster Street were built more for movies than live performances.

In 1976 Roger Brett wrote Temples of Illusion – The Golden Age of Theaters in an American City. This account brings the story of the theaters of Providence up to the late 1940s and is most useful. It is well illustrated but unfortunately does not have an index. Brett ended his account with what he called “the TV saturated days of the 1950s.”

Yet, theater in Providence is still very much active and vibrant. Two of the old theaters are still in use today, the Lowe’s State is now the Providence Performing Arts Center and the Majestic, now the Lederer, is home to Trinity Repertory Company. The show goes on.

Notes

[1] The motto on a banner that hung over the proscenium of the Providence Theater on Westminster Street, the city’s first theater. [2] Manufacturers and Farmers Journal, January 2, 1865. [3] The Providence newspaper The Morning Star reported the day following the opening that the theater was “crowed from pit to dome.” The article went on to say, “The audience was not only a large one, but especially brilliant, composed of the most fashionable and select of Providence society.” [4] Reeves was not only the bandleader but a composer and cornetist. He is best known for his composition Second Regiment Connecticut National Grand March. John Phillip Souza said of Reeves that he was “The Father of Band Music in America.” [5] It was said that Sir Arthur Sullivan, the composer of H.M.S. Pinafore, sent Reeves a letter of commendation when he heard about the performance at Park Garden. [6] On April 4, 1930, newspapers announced that the Albee Players would be discontinued. One article in the Pawtucket Times noted “Foster Lardner, manager of the Albee Theatre, in a prepared statement, declared that the decision of the officials was reached after a conference in New York, where it was determined that continuance of the Albee stock company this summer would be impractical because of the lack of good plays on the market. Most of the plays available are of a sexy nature, it was declared, and were deemed unsuitable for presentation by the Albee Players. Another factor which influenced the RKO officials in their decision was that many of the plays which might be obtained have already been done in the talks.” Days later Edward M. Fay, theater owner and impresario, was quoted as saying he had signed most of the Albee players under the name Providence Stock Company and that they would perform at the Carlton Theater.