For Westerly, selecting and installing a mural for the Westerly Post Office during the term of the New Deal Program from 1934 to 1943 to install art in public areas proved to be a challenging and, ultimately, futile process.

The government handed over this public arts program to the Treasury Section of Fine Arts, not to the Works Project Administration (WPA) as is commonly thought. The Treasury Section of Fine Arts maintained control over the program, making decisions, as will become evident, while knowing nothing about local desires or history.

The program had three goals: to provide money for struggling artists, regardless of talent (it was the Great Depression and artists needed living wages too); to educate rural Americans about “fine art”; and to cater to public taste. The first two goals could be contradictory and often the federal government knew nothing about the third. An unspoken agreement was that the murals should have an historic subject, which recreated real or imagined events, thus calming public fears about the Great Depression as viewers saw the long chain of history on the wall before them and felt that everything would be okay.

Often the artists flattened images, adjusted the scale of objects rather than striving for pictorial accuracy, and featured technological or industrial subjects. There was a certain element of cubism, popular at the time, in many of them.

Three Ps were necessary for success. The Patron (the government) wanted “good art” to improve American taste. The Painter was often caught in the middle. The Public knew what it wanted and what it did not want and that differed from place to place.

The government wanted the mural to have a connection to the local geographic area, but artists could not always travel to a specific area since they did not receive payment until the design had been submitted to the government. The painter often had to travel to do research; send in all sketches, cartoons, and photos to Washington, D.C. at the painter’s own expense; buy the canvas, paint, varnish and adhesive; hire a professional photographer to document the installation; and submit color sketches to scale to the government for it to keep, thus not allowing the artist to sell to a local art collector and make some money. The public, in general, did not want any mural that could cast a negative light on the locality, even if the subject or the portrayal of it was true.

Westerly got caught in the swirl of issues involved in these assumptions and requirements.

Rural communities often had a collective vision of prosperity through technology, and it seemed that anything with wheels—tractors, airplanes, trains—seemed to represent a guarantee of a prosperous future.

Historical murals, whether of a real or imagined event, gave a sense of the stability of people working together for the good of the whole. Often, it celebrated a dubious “first” or someone born there and who made it big somewhere else or froze and enshrined an idyllic picture of the past. Essentially, the mural said, “If we have survived this long, the future will be okay.”

Westerly could have celebrated the arrival of the Babcock family in late 1640s as the first European settlers. In fact, students at the Westerly Middle School chose that subject for one of the wall murals that student artists painted at the school (the mural still exists).

Other communities wanted an example of local industry, which gave them a feeling of stability and “home” and perhaps insulated them from the outside world and events beyond their control. Using those standards, it appeared that Westerly’s famous granite industry, despite it having fallen on hard times by the start of the Great Depression, was the best fit as the topic for a mural.

In 1939, the Treasury Section of Fine Arts (called the Section) decided to hold a contest. A rural post office in each state would receive a mural and Life Magazine would print the photos of the winning sketches. The basic rules included a prize for each winning artist of $725 (but remember all the artist’s expenses), and the guidance that the mural should feature some sort of local history, past or present. In total, countrywide, 972 artists submitted 1,477 designs to the Section. The December issue of Life Magazine featured 48 postage stamp-sized designs. [Editor’s note: there were then 48 states, Alaska and Hawaii not yet admitted as states.]

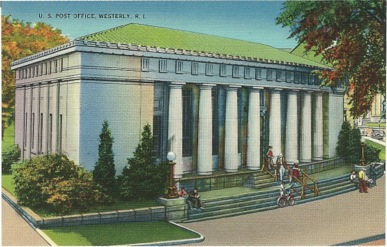

Part of the WPA plan was to build new post offices and courthouses that would be ideal places for the murals, but Westerly had a relatively new post office that had been built in 1912. A group of local citizens had formed the Citizens-Taxpayers of Westerly and begun agitating for a new post office about six months before the Section was founded. The Executive Board got so excited about the possibility of a mural appearing in the town’s “new” post office that the Board sent away for the Section guidelines for the artwork. They were ready.

The Board members may have been ready prematurely, as, at the time the 48 States Competition was announced, the “new” Westerly post office was still in the preliminary drafting stage. Funds for the mural had not been authorized and things were a bit fuzzy, including just what the artists should submit as proposals.

Westerly’s 1912 post office was a beautiful marble (not granite) edifice. There was always the risk that the federal government would have selected as the replacement post office the same boring design as was the standard, with about 42 feet of frontage. If so, the mural would be placed on the end wall over the postmaster’s door, which was flanked by, and a little higher than, two bulletin boards featuring news and wanted posters. This placement could provide some design challenges. By contrast, Westerly’s existing Post Office building had no impediments over the middle section, as it had two doors, one for the postmaster and another for the assistant postmaster. Everything lined up nicely.

The current interior of the Westerly Post Office, showing where a mural could be placed (Ellen L. Madison)

The day came when the winners of the local contests across the country were announced. Rhode Islanders may be familiar with the mural at the Wakefield Post Office. It was not part of the contest, but it was typical of the designs that tried to capture local history. Titled “South County Life in the Days of the Narragansett Planters,” it met with great local enthusiasm, despite containing elements such as slavery which could be interpreted negatively.

The Westerly Sun printed a glowing review of the new Wakefield Post Office mural. Here are a few excerpts: “It is intended to depict South County’s past and portrays the 18th century days of South County planters, who counted their wealth largely in slaves and rum.” “There is a group of cattle, horses, and slaves in the center and foreground of the design.” “In the center is a brightly dressed planter astride a fine horse.” “[I]n the background are the sailing ships … ready to carry the products of the South County to distant ports and return bringing slaves and rum.” Also mentioned are the fine Narragansett pacers, highly prized dairy cows, Narragansett cheese, corn for Rhode Island jonny cake meal, and the ever-present outcropping of rocks and boulders. The artist certainly packed a great deal into that mural. (This extraordinary mural can be seen today at the South County History Center in Kingston.)

The mural that was shown in the Wakefield Post Office for many years, known as The Economic Activities of the Narragansett Planters. This image was taken after its restoration in 2000 (South County History Center).

Given the positive reception of the post office mural in Wakefield, one might expect that local communities would be pleased with the contest winners announced in December of 1939. Not so.

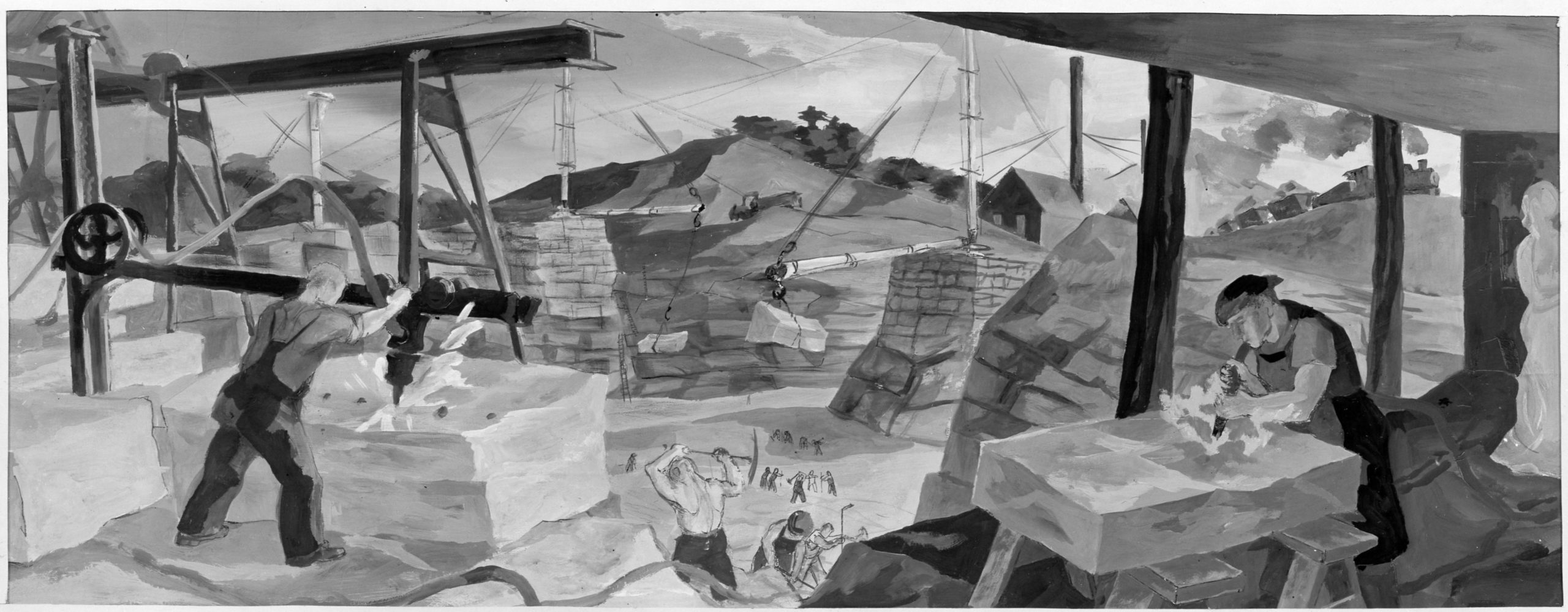

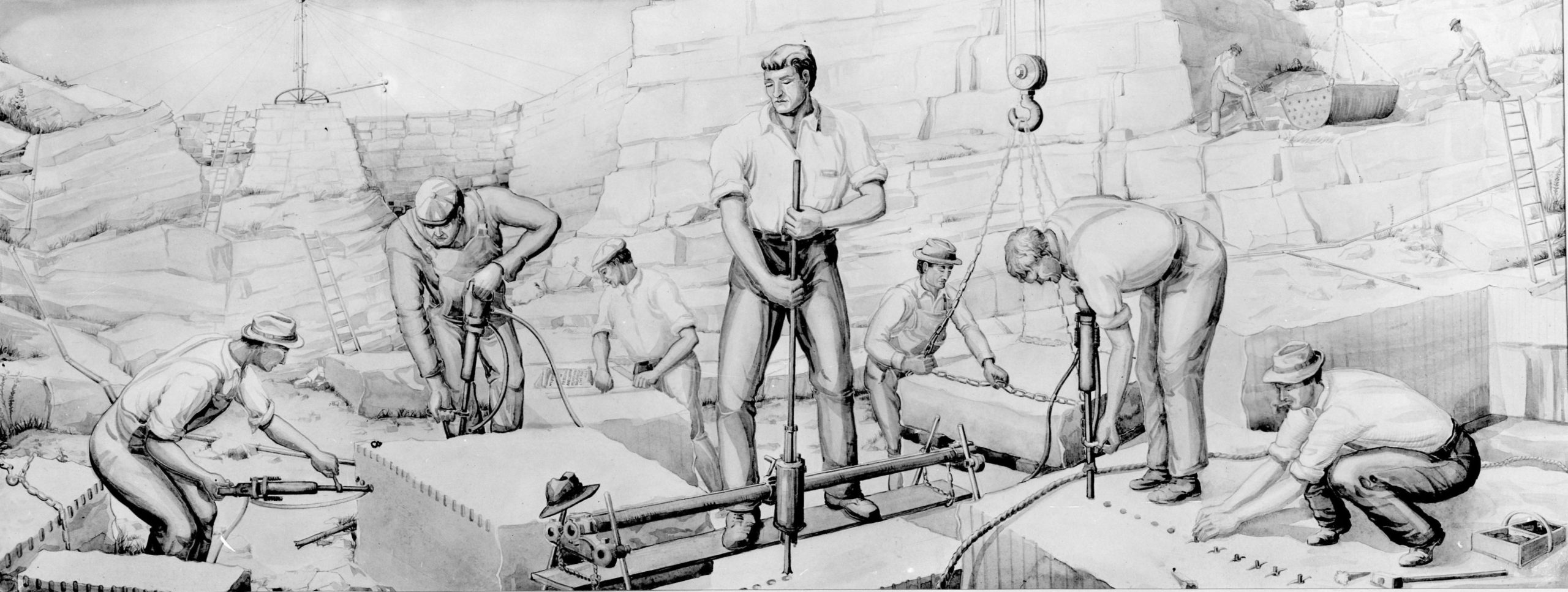

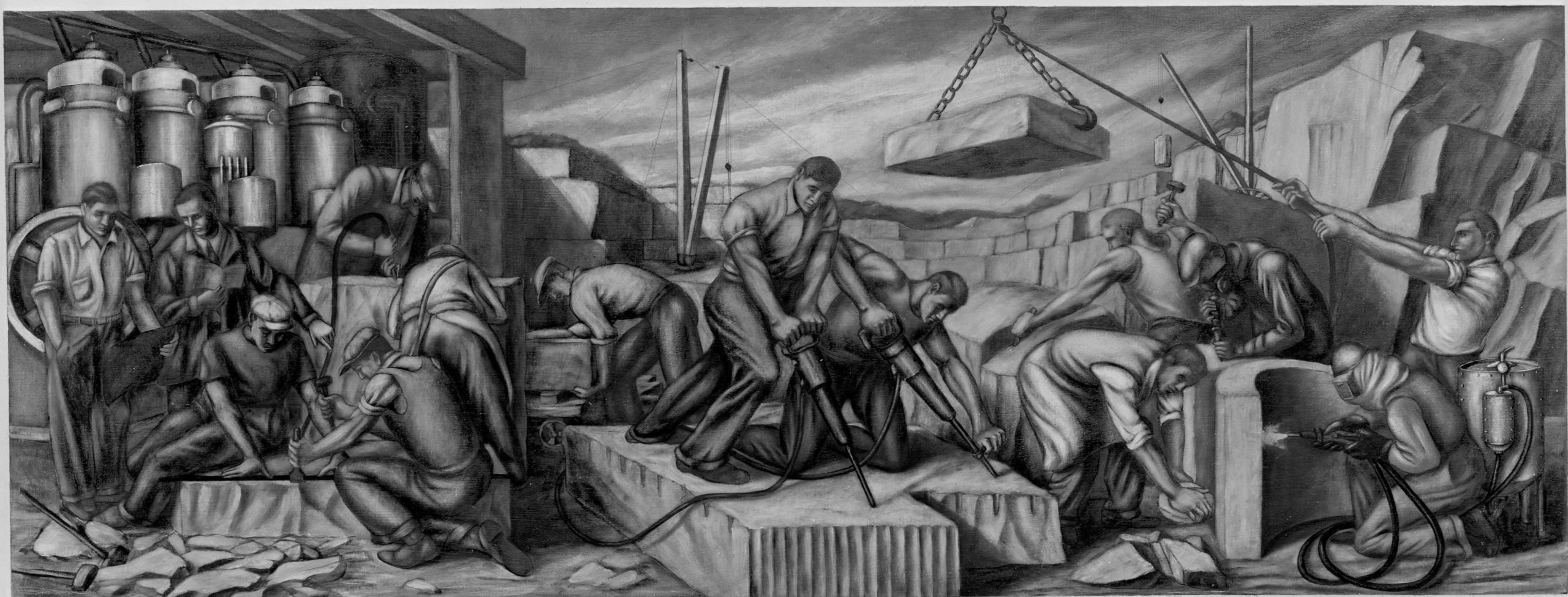

We still have photos of some of the sketches submitted for the Westerly post office, many held by the National Archives. Amazingly, they all show Westerly’s granite workers at work. In alphabetical order, four are:

Bruce Mitchell (1908-1963), born in Scotland. He submitted one featuring his version of Westerly’s granite industry.

Leo Raiken, a New York City artist, submitted a charcoal on paper study entitled, The Rock Quarry.

Paul Rudin, a sculptor born in Germany, was noted for his sculpture of animals, but he submitted one of men working in a quarry.

Alfreo Verrechio, the only local person to submit, was born in Providence. He was also a graduate of the Rhode Island School of Design. By profession he was a lithographer, painter, and designer. He was also President of the Gem-Craft in Cranston. He too submitted a study of Westerly quarry workers.

So, all four submissions dealt with granite. Which one won the contest? The answer is a startling: NONE.

Instead, Paul Starret Sample’s A Railroad Engineer and His Family Crossing Over the Tracks at the Station in Westerly RI was selected by the Section. It was a scene of Westerly’s train station, or at least it purported to be. A train worker is seen walking, with his family, on an overpass that did not exist Full of sharp angles and picturing something completely foreign to the Westerly train station, it was described as follows: “The style is metallic and modern and the sketch is controlled by a lateral thrust following the sharp place of the railroad tracks. A caboose, box cars and an updated steam locomotive wrapped in a streamlined shroud also describe a horizontal band across the design surface . . . .“ Had enough?

Paul Starret Sample’s winning submission A Railroad Engineer and His Family Crossing Over the Tracks at Station, Westerly, Rhode Island (National Archives)

Outrage in Westerly followed.

The Citizen-Taxpayers Committee of Westerly issued a strong statement. “Therefore a vigorous protest is hereby registered against the placing of such a misconception and ill-advised understanding of this historical town and its leadership in one of the oldest and most substantial industries, a native product GRANITE.”

The December 7, 1939, issue of the Westerly Sun stated “It looks as if those who had a chance to choose some 45 murals for the post offices of the country had made the best selections possible for the other states and handed Westerly what was left over. Westerly has no overpass. It has a subway. It is doubtful if there is a single railroad engineer who resides in Westerly. Westerly certainly is not anything of a railroad center and has no ambition to be one. . . . The buildings are characteristic of a dilapidated Pennsylvania coal mining town.”

The Providence Journal’s December 6 edition stated: “There’s a slogan put out by the Westerly Chamber of Commerce . . . that the town is a ‘good place to live, work and play’ . . . the Chamber will have to tack an addition to the slogan, pointing out that it’s also a good place for railroad engineers. . . .they unanimously agree it’s inclined to make a man mighty homesick—for Gary, Indiana.”

Frank Sullivan, owner of Sullivan Granite Company, which produced fine Blue-White Westerly granite, and also serving as president of the Westerly Chamber of Commerce, wrote, “There is no overhead bridge at the railroad station and never [has] been, and it seems to us a more appropriate subject could have been selected for this New England town where for over 100 years our citizens have found employment cutting and carving Westerly granite, and later making 4 color rotary presses for national magazines and textiles, and earned a livelihood in many of their diversified industries.”

Interestingly, Westerly native Alexander G. Sawyer had submitted a granite quarry sketch of which the major groups in Westerly approved, but, alas, it did not place in the judging and was returned to go on display in Westerly’s public library.

There had been fourteen Rhode Island designs submitted, at least five of which dealt exclusively with the granite industry. Most did not have the “artistic merit” of Sample’s railroad design but did have the “concern with the human dimension of industry, and the tools and techniques men used to earn a livelihood.”

Page from Life Magazine’s December 4, 1939 edition showing some of the winning murals for the 48 states

Comments on the sketches featuring granite showed the importance of granite to the people of Westerly. Some are visual instructive guides to quarrying. Some show modern machinery working with or against human strength. Each man holds, touches, grabs, grips, or seizes something and, together, they are a part of a collective force of human beings, indicating that this product is not an individual accomplishment. The tools are less important than the hands, but together they show a combination of old and new technology. The act of working with granite was the history of the last nearly one hundred years of Westerly and it did not make a difference whether the men worked with old or new technology. What was important was that they worked. By 1939, there had been a decade-long slump in the local granite industry and people were scared. Unemployment loomed even as granite lay in the ground. Those hands grasping or reaching for their tools were reassuring in many ways.

Evidently, the Section listened to these comments and went back to Leo Raiken’s submission. We are fortunate that many figure studies still exist and we know that he modified his final submission, which was 12 feet long and 6 feet high showing some changes. One of the images of this article shows the modified mural.

One of many existing individual figure studies drawn by Leo Raiken for his submission (National Archives)

What did Raiken change? The compressors are bigger, perhaps indicating that technology was a sign of the future. A big block of granite hanging in the air is gone. Did it detract from the concept of the importance of men working or was it artistically better to get rid of it? Thirteen men became twelve. One of the derricks is gone. Success seemed near for Westerly to get a mural with which it could be happy.

BUT Pearl Harbor happened. Commissions to artists not already bound by signed contracts were canceled. Artists signed up or were drafted to serve in the armed forces. The Section’s 1943 final report stated that 1,116 murals were completed.

And Westerly? No mural was ever installed at Westerly.

Still, there was good news: Westerly’s historic and beautiful Post Office was saved and not replaced. It is still being used today, even if there is no Great Depression era mural in it.

Acknowledgements:

Most of the information for this article derives from Wall to Wall America: Post Office Mural in the Great Depression by Karol Ann Marling.

The National Archives in Washington, D.C. made available images of various submissions for the Westerly Post Office.

The Wolfsonian Museum at Florida International University supplied images of Raiken’s studies.

The Westerly Library made available Westerly Sun articles.

Joseph E. Coduri provided the historic postcard of the Westerly Post Office.