[From the Editor: In the late 17th and early 18h centuries, Rhode Island was a haven for pirates. That changed in 1723 when Charles Harris and twenty-five other pirates were hanged at Gravelly Point off Long Wharf in Newport. The bodies of the dead pirates were carried to Goat Island, where they were buried between the high and low water marks. The following description by the above authors of how the pirates came to be hanged is from a chapter in the book titled The Pirates of the New England Coast, 1630-1730 (Rio Grande Press, 1923). Minor revisions have been made based on modern spelling, punctuation and usage. The word “gaol” has been retained; it means jail.

Update: I am pleased to report that a book has been recently published that contains the most detailed, accurate and well-written account of HMS Greyhound’s tracking and capture of the pirate Edward Low’s ship Ranger and, the trial and hanging of the twenty-six captured pirates at Newport. The book is: Len Travers, The Notorious Edward Low, Pursuing the Last Great Villain of Piracy’s Golden Age (Westholme, 2023). You can order the book from the publisher’s website here: https://www.westholmepublishing.com/book/notorious-edward-low-travers/

It is sometimes said that the hanging of the twenty-six pirates at Newport was the largest public mass execution in American history. It is not true. That occurred when thirty-eight Santee Sioux were hanged at Mankato, Minnesota on December 16, 1862, after the Sioux went on a killing spree as a result of frustration with the U.S. not honoring its treaties. On November 8, 1718, it appears that at least twenty-two pirates, and maybe more, were hanged at White Point near Charleston, South Carolina (their leader, Stede Bonnet, was hanged ten days later). There were also mass hangings of enslaved people in retaliation for slave uprisings. All very horrible.]

On the 10th day of January, 1722, the good ship Greyhound of Boston in Massachusetts Bay, Benjamin Edwards, commander, was homeward bound. She was loaded with logwood and only one day out from the coast of Honduras where the crew had been worked hard for several weeks loading the many boatloads of heavy, thorny-growthed, blood-red wood. Early in the morning the lookout had sighted a ship headed toward them and while not plantation built she attracted no particular attention until it was seen that her course was slightly changed to conform to that of the Greyhound, or rather, it would seem, to intersect the course on which the Greyhound was sailing. As the ship drew nearer, a long look through the perspective revealed a heavily-manned vessel of English build. Captain Edwards thought it best to order all hands on deck. Soon the stranger ran up a black flag having a skeleton on it and fired a gun for the Greyhound to bring to.

West India waters had been plagued for many years by pirates and the Boston captain had heard many terrifying tales of their barbarous cruelties to masters and seamen but he was a dogged type of man and so at once prepared to defend his ship. The pirate vessel edged down a bit and shortly gave the Greyhound a broadside of eight guns which Captain Edwards bravely returned. For nearly an hour the give and take continued at long gunshot without much damage to either vessel. Finding that the pirate was more heavily armed than the Greyhound, and her decks showing many men, Captain Edwards began to reckon the consequences of a too stubborn resistance, for it seemed likely that eventually he must surrender, barring, of course, a lucky chance shot from his guns that might cut down a mast on the pirate ship. At last he ordered his ensign to be struck and hove to. Two boatloads of armed men soon came aboard and searched the ship for anything of value. The loot was not great for the New England logwood ships had little opportunity for trade or barter and the disappointment of the pirate crews was soon spit out on the men. Whenever one came within reach of the cutlass of a pirate he would receive a swinging slash across shoulders or arms, or perhaps, a blow on the head with the flat of the blade that would fell him half-senseless to the deck. By way of diversion two of the unoffending sailors were tied up at the foot of the mainmast and lashed until the blood ran from their backs. Captain Edwards and his men were then ordered into the boats and sent on board the pirate ship and the Greyhound was set on fire.

The rogue proved to be the Happy Delivery, commanded by Capt. George Lowther and manned by a strange assortment of English sailors and soldiers with a sprinkling of New England men. As soon as the men from the Greyhound reached her deck they were given a mug of rum and invited to join the pirate crew. This was habitually done at that time by these outlaws and frequently a nimble sailor would be forced and compelled to serve with the pirates against his will.

The first mate of the Greyhound was Charles Harris, born in London, England, then about twenty-four years old and a man who understood navigation. He, with four others, Christopher Atwell, Henry Smith, Joseph Willis and David Lindsay, were forced. Captain Edwards and the rest of his crew, with other captured men, were put on board another logwood vessel and permitted to make the best of their way home. In a day or two, Harris, beguiled by the adventurous spirit of the ship’s company, was persuaded to sign the Articles of the Happy Delivery, when again asked to do so by Captain Lowther. He proved to be so capable a man, when several captures were made, that ten days later, when a Jamaican sloop was taken, Lowther decided to retain her and give the command to Harris and to this he readily acceded.

The mate of the Happy Delivery was Ned Low, a young Englishman who had lived in Boston for a few years and not long before this time had deserted from a logwood ship in the Bay and happening to meet Lowther had joined him in a career of robbery and murder. Just before the Jamaican sloop was taken, a Rhode Island sloop of about one hundred tons was captured and as she was newly built was taken over by Lowther and armed with eight carriage guns and ten swivels and the command given to Low.

The career of Harris during the next fourteen months closely follows that of Lowther and Low and may be traced in the narrative of their adventures. He soon lost his sloop when it was abandoned at sea in the Gulf of Matique. On May 28th, 1722, when Lowther and Low separated, Harris cast his lot with Low and sailed north with him along the New England coast to Nova Scotia and then across the Atlantic to the Western Islands, where a large Portuguese pink was taken and retained and the command of the schooner Fancy given to Harris. These two scoundrels cruised together for some time making several captures and at length reached the Triangles off the South American coast, eastward of Surinam, and here the pink was lost while being careened. Both crews went on board the schooner where Low again assumed command. Before long a large Rhode Island-built sloop was captured which Low took over and having had a falling out with Harris, the command of the schooner Fancy was given to Francis Farrington Spriggs, who had been serving as quartermaster.

Harris now drops out of sight for about five months. He may have been wounded or sick at the time Spriggs was given his command. At any rate, no mention of his name has been found until May 27, 1723, when he appeared off the South Carolina coast in command of the sloop Ranger, lately commanded by Spriggs. Captain Low was sailing in company with him in the sloop Fortune, and together they took three ships. About three weeks before, they had captured the ship Amsterdam Merchant, from Jamaica but owned in New England. The master was John Welland of Boston and after he had been on board the Ranger for some three hours he was transferred to the Fortune, where Low vented his spite against New Englanders by cutting the captain about the body with his cutlass and slashing off his right ear.

A month later, at the trial of Captain Harris at Newport, R. I., this Captain Welland was the principal witness against him. He deposed that he had been chased by two sloops and that one of them came up with him and after hoisting a blue flag had taken him. This was the Ranger, with Harris in command. He had been ordered aboard the pirate sloop and had gone with four of his men. The quartermaster had examined him and asked how much money he had on board, and he had replied “About £150 in gold and silver.” This money was taken away by the pirates. Meanwhile Captain Low in the Fortune, came up and Welland was sent aboard to be interrogated where he was greatly abused. The next day, after taking out a negro, some beef and other stores, the Amsterdam Merchant was sunk. While the three vessels were lying near each other, Captain Estwick of Piscataqua, N. H., came in sight and soon fell into the clutches of Low and Harris. His ship was plundered but not destroyed and in this vessel Captain Welland and his men at last reached Portsmouth.

Off the Capes of the Delaware other minor captures were made by Low. Steering eastward along the Long Island shore early on the morning of the 10th of June a large ship was sighted which soon changed its course and the two pirate sloops at once followed in pursuit. What then took place may best be told in the words of the newspaper account written at the time. [What follows is a narrative from an officer on board the warship Greyhound of its capture of Harris’s pirate sloop.]

“Rhode Island, June 14. On the 11th Instant arrived here His Majesty’s Ship Greyhound, Capt. Peter Solgard Commander, from his cruise at sea and brought in a pirate sloop of 8 guns, Bermuda built, 42 white men and 6 blacks, of which number eight were wounded in the engagement and four killed. The sloop was commanded by one Harris, very well fitted, and loaded with all sorts of provisions. One of the wounded pirates died, on board of the man-of-war [the Greyhound], with an oath on his departure. Thirty lusty bold young fellows, were brought on shore, and received by one of the town [Newport] company’s under arms guarding them to the goal [Newport jail], and all are now in Irons under a strong guard. The man-of-war had but two men wounded, who are in a brave way of recovery.

“Here follows an Account (by a sailor on board of the man-of-war) of the engagement between Capt. Solgard and the two pirate sloops. Capt. Solgard being informed by a vessel, that Low the pirate, in a sloop of 10 guns and 70 men, with his consort of 8 guns and 48 men, had sailed off the east end of Long Island. The captain thereupon steered his course after them. On the 10th current, half an hour past 4 in the morning, we saw two sloops north two leagues distance, the wind W.N.W. At 5 we tacked and stood southward, and cleared the ship, the sloops giving us chase, at half an hour past 7 we tacked to the northward, with little wind, and stood down to them; at 8 a Clock they each fired a gun, and hoisted a black flag. At half an hour past 8 on the near approach of the man-of-war, they hauled it down (fearing a Tartar) and put up a Bloody Flag, stemming with us distant three-quarters of a mile. We hoisted up our main sail and made easy sail to the windward, receiving their fire several times. But when abreast we gave them ours with round and grapeshot, upon which the head sloop edged away, as did the other soon after, and we with them. The fire continued on both sides for about an hour, but when they hailed from us with the help of their oars, we left off firing, and turned to rowing with 86 hands. At half an hour past two in the afternoon we came up with them. When they clapped on a wind to receive us, we again kept dose to windward, and plied them warmly with small and grape shot. During the action we fell between them, and having shot down one of their main sails we kept close to him. At 4 a clock he called for quarters [the ship surrendered]. At 5 having got the prisoners on board, we continued to chase the other sloop, when at 8 a clock in the evening he bore from us N.W. by W. two leagues, when we lost sight of him near Block Island. One desperado was for blowing up this sloop rather than surrendering, and being hindered, he went forward, and with his pistol shot out his own brains.

“Capt. Solgard designing to make sure of one of the pirate sloops, if not both, took this, seeming to be the chief, but proved otherwise. If we had more daylight the other of Low’s had also been taken, she being very much battered. It is thought he was slain, with his cutlass in his hand, encouraging his men in the engagement to fight, and that a great many more men were killed and wounded in her, than the other we took.

“The two pirate sloops commanded by the said Low and Harris intended to have boarded the man-of-war, but he plying them so successfully they were discouraged, and endeavored all they could to escape, notwithstanding they had sworn damnation to themselves, if they should give over fighting, though the ship should even prove to be a man-of-war. They also intended to have hoisted their standard upon Block Island, but we suppose now, there will be a more suitable standard hoisted for those that are taken, according to their deserts.

“On the 12th current Capt. Solgard was fitting out again to go in the quest of the said Low, the other pirate sloop, having the master of Harris’s vessel with him, he knowing what course they intended by agreement to steer, in order to meet with a third consort which, we hope he’ll overtake and bring in.” — Boston News-Letter, June 20, 1723.

The New England Courant of Boston, Franklin’s newspaper [James Franklin, Ben’s older brother], printed a similar account of the fight and capture and also mentioned the fact that Joseph Sweetser of Charlestown was one of the men taken and that both he and Charles Harris, who is the “master or navigator,” had previously been advertised in the public prints as forced men, with one or two more of the company. A week later the Courant published a list of the names of the men, as follows.

“An Account of the Names, Ages, and Places of Birth of Those Men Taken by his Majesty’s Ship Greyhound, in the Pirate Sloop called the Ranger, and now Confined in his Majesty’s Gaol in Rhode-Island.

Names Ages Places of Birth

William Blades 28 Rhode Island

Thomas Powell, Gunner 21 Wethersfield, Conn.

John Wilson 23 New London County [Conn.]

Daniel Hyde 23 Eastern Shore of Virginia

Henry Barnes 22 Barbadoes

Stephen Mundon 29 London [England]

Thomas Huggit 24 London

William Read 35 Londonderry, Ireland

Peter Kewes 32 Exeter, England

Thomas Jones 17 Flint, Wales

James Brinkley 28 Suffolk, England

Joseph Sawrd 28 Westminster [England]

John Brown 17 Liverpool [England]

William Shutfield 40 Leicestershire, Engl.

Edward Eaton 38 Wreaxham, Wales

John Brown 29 County of Durham, Engl.

Edward Lawson 20 Isle of Man [England]

Owen Rice 27 South Wales

John Tomkins 23 Glocestshire, Engl.

John Fitzgerald 21 County of Limerick, Ireland

Abraham Lacey 21 Devonshire, Engl.

Thomas Linisker 21 Lancashire, England

Thomas Reeve 30 County of Rutland, England

John Hinchard, Doctor 22 Near Edinburgh, Scotland

Joseph Sweetser (forced) 24 Boston, New England

Francis Layton 39 New York

John Walters, Quartermaster 35 County of Devon, England

William Jones 28 London, England

Charles Church 21 Westminster, England

Tom Umper, an Indian 21 Martha’s Vineyard

In all 30

—New England Courant, June 24, 1723.

The following seven were held on board the Greyhound by Captain Solgard, who hoped through them to take Low. They were brought back to Newport and gaoled on July 11th. One of the pirates died in gaol on July 15th.

Charles Harris, Captain 25 London

Thomas Hazell 50

John Bright 25

Joseph Libbey 21 Marblehead

Patrick Cunningham 25

John Fletcher 17

Thomas Child 15

When the news of this great capture of pirates reached the seaport towns along the New England shore there was much rejoicing. Nothing like it had ever happened in the history of the colonies. To be accused of piracy at that time, with any show of evidence, was very nearly equivalent to being found guilty, so a great gathering of people was assured for the hangings soon to follow.

Three weeks later the Honorable William Dummer, Esq., Lieutenant-Governor and commander-in-chief of His Majesty’s Province of the Massachusetts Bay in New England, together with divers members of His Majesty’s Council and other gentlemen from that Province came riding into the town of Newport, and with Governor Cranston of Rhode Island and other judges duly commissioned by Act of Parliament proceeded to open a Court of Admiralty for the trial of the pirates. The trial was held in the town house on Wednesday morning, July 10, 1723. The Court was authorized by Act of Parliament made 11 and 12 William III; made perpetual by Act of 6 George I. The Court organized, and then adjourned until eight o’clock in the morning of the next day when Charles Harris and twenty-seven others were brought to the bar and arraigned for acts of felony, piracy and robbery.

The facts connected with the taking of the ship Amsterdam Merchant, with the presence in court of the master and some of his men, were in themselves sufficient to hang the accused. Captain Solgard of the man-of-war, who had fought with the accused pirates and captured them, also testified as did his lieutenant and surgeon. The presence of these men in court together with the reputed facts of the chase and capture decided the case in the minds of the people before the evidences were offered or the verdict rendered. John Valentine, the Advocate General for the King, presented the articles, which accused the prisoners of piratically surprising and seizing the ship Amsterdam Merchant and carrying away beef, gold and silver and a negro slave named Dick, and cutting off Captain Welland’s right ear and afterwards sinking the ship valued at one thousand pounds. They were also accused of piratically attacking His Majesty’s ship, the Grey Hound, and wounding seven of his men.

The prisoners were not represented by counsel, but they all pleaded “not guilty,” and fourteen of them were ordered tried at that very session. The Advocate General addressed the Court as follows:

“May it please your honor, and the rest of the honorable judges, of this court.

“The prisoners at the bar stand articled against and art prosecuted for, several felonious piracies and robberies by them committed upon the high sea. To which they several pleaded not guilty.” The crime of piracy is a robbery (for piracy is a sea term for robbery) committed within the jurisdiction of the admiralty.

“And a pirate is described to be one who to enrich himself either by surprise or open force, sets upon merchants and others trading by sea, to spoil them of their goods and treasure, often times by sinking their vessels, as the case will come out before you.

“This sort of criminal is engaged in a perpetual war with every individual, with every state, Christian or infidel. They have no country, but by the nature of their guilt, separate themselves, renouncing the benefit of all lawful society, to commit these heinous crimes. The Romans therefore justly styled them, Hostes humoni generis enemies of mankind, and indeed they are enemies and armed, against themselves, a kind of felons de se — importing something more than a natural death.

“These unhappy men satiated with the number and notoriety of their crimes, had filled up the measure of their guilt, when by the Providence of Almighty God, and through the valor and conduct of Captain Solgard, they were delivered up to the sword of justice.

“The Roman Emperors in their edicts made this piece of service so eminent for the public good, as meritorious as any act of piety, or religious worship whatsoever.

“And it will be said for the honor and reputation of this colony (though of late scandalously reproached, to have favored or combined with pirates), and be evinced by the process and event of this affair, that such flagitious persons find as little countenance, and as much justice at Rhode Island, as in any other part of His Majesty’s dominions.

“But your time is more precious than my words, I will not misspend it in attempting to set forth the aggravations of this complex crime, big with every enormity, nor in declaring the mischiefs and evil tendencies of it; for you better know these things before I mention them; and I consider to whom I speak, and that the judgment is your honors.

“I shall therefore call the King’s evidences to prove the several facts, as so many distinct acts of piracy charged on the prisoners, not by light circumstances and presumptions, not by strained and unfounded conjectures, but by clear and positive evidence. And then I doubt not, since for it is the interest of mankind that these crimes should be punished. Your honors will do justice to the prisoners, this colony, and the rest of the world in pronouncing them guilty, and in passing sentence upon them according to law.”

Capt. John Welland then testified as to the facts attending the capture of his ship. He also said that Henry Barns, one of the prisoners at the bar, was forced out of his ship at the time it was taken and was “very low and weak” and when on board Captain Eastwick’s vessel (in which they had at last reached Portsmouth) Barns had tried to get away and hid himself. But the pirates threatened to burn the ship unless he was given up so Barns was compelled to go on board the pirate sloop. Barnes had cried and ” took on very much” and asked the mate of the Amsterdam Merchant to notify his three sisters living in Barbadoes that he was a forced man and also very sick and weak at the time. The mate and the ship’s carpenter confirmed the captain’s testimony that all the pirates were “harnessed, that is, armed with guns, etc.”

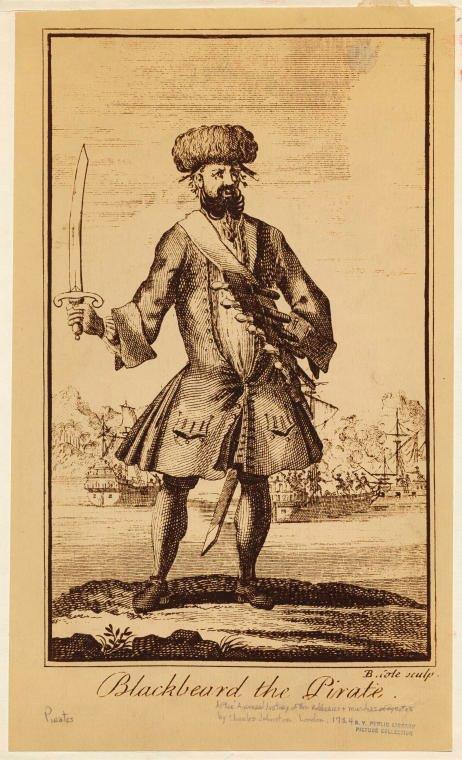

Blackbeard the Pirate. From a General History of the Robberies & Murders of Pyrates by Charles Johnson, London, 1724 (New York Public Library). Fourteen of Black Beard’s pirates were hanged at Williamsburg, Virginia, in March 1719. Along with the hangings at Newport and Charleston, they helped to end the scourge of piracy.

Capt. Peter Solgard, Lieut. Edward Smith, and Archibald Fisher, Chief Surgeon of the Greyhound man-of-war, testified to the well known facts of the engagement with the pirates and William Marsh, a mariner, made oath that he had been taken by Low’s company in the West Indies the previous January and that “he saw on board the schooner at that time Francis Laughton and William [no last name given] and on board the sloop, Charles Harris, Edward Lawson, Daniel Hyde, and John Fitzgerald, all prisoners at the Bar, and that Fitzgerald asked him whether he would seek his fortune with him.” This concluded the testimony and the prisoners were then severally asked if they had anything to say in their own defense. Without exception each man said that he had been forced on board of Low and did nothing voluntarily.

The Advocate General then summed up the case, as follows:

“Your Honors, I doubt not have observed the weakness, and vanity of the defense which has been made by the prisoners at the bar, and that the articles (containing indisputable flagrant acts of piracy) are supported against each of them. Their impudences and unfortunate mistake, in attacking His Majesty’s ship, though to us fortunate, and of great service to the neighboring governments. Their malicious and cruel assault upon Capt. Welland, not only in the spoiling of his goods, but what is much more, the cutting off his right ear, a crime of that nature and barbarity which can never be repaired. Their plea of constraint, or force (in the mouth of every pirate) can be of no avail to them, for if that could justify or excuse! No pirate would ever be convicted; nor even any profligate person in his own account offend against the moral law; if it were asked, it would be hard to answer, who offered the violence? It’s apparent they forced, or persuaded one another, or rather the compulsion proceeded of their own corrupt and avaricious inclinations. But if there was the least semblance of truth in the plea, it might come out in proof, that the prisoners or some of them did manifest their uneasiness and sorrow, to some of the persons whom they had surprised and robbed. But the contrary of that is plain from Mr. Marsh’s evidence that the prisoners were so far from a dislike, or regretting their number by inviting him to join with them, and seemed resolved to live and die by their calling, or for it, as their fate is like to be. And now seeing that the facts are as evident as proof by testimony can make them, I doubt not your honors will declare the prisoners to be guilty.”

The prisoners were then taken from the bar, the court room was cleared and the judges considered the evidence and voted that all were guilty except John Wilson and Henry Barns. The Court then adjourned for dinner and at two o’clock met and opened by proclamation. The prisoners were brought in and those found guilty were sentenced by Lieut.-Governor Dummer to be hanged by the neck until dead. Thirteen more “of that miserable crew of men,” as they were characterized by the Advocate General, were then brought to the bar for trial. Captain Welland named six of them whom he recognized as having been on the Ranger and all had been harnessed, except Thomas Jones, the boy. John Mudd, the carpenter, said that he well remembered Joseph Sound because “said Sound took his buttons out of his sleeves.”

“Benjamin Weekham of Newport mariner, deposed, that on the tenth of March last he was in the Bay of Honduras on board of a sloop, Jeremiah Clark Master. Low and Lowther’s companies being pirates took the aforesaid sloop and this deponent then having the small pox was by John Waters one of the prisoners at the bar was carried on board another vessel, and that he begged of some of the company two shirts to shirt himself. The said Waters said damn him, he would beg the vessel too, but at other times he was very civil. The deponent further said he saw William Blades now prisoner at the bar amongst them.

“William Marsh deposed, that he was taken in manner as aforesaid, and that John Brown the tallest was on board the schooner, and the said Brown told him he had rather be in a tight vessel than a leaky one, and that he was not forced.

“Henry Barns mariner, deposed, that he being on board the Sloop Ranger during her engagement with the Greyhound man-of-war saw all the prisoners at the bar on board the said sloop Ranger, that he saw John Brown the shortest in arms, and that Thomas Mumford Indian, was only a servant on board.

“The prisoners at the bar were then asked if they had anything to say in their own defense.

“William Blades said he was forced on board of Low about eleven months ago, and never signed to their articles, and that he had when taken about ten or twelve pounds, and that he never shared with them, but only took what they gave him.

“Thomas Hugget said he was one of Capt. Mercy’s men on the coast of Guinea, and in the West Indies was put on board Low, but never shared with them, and they gave him twenty-one pounds.

“Peter Cues said, that on the twenty-third or twenty-fourth of January last he belonged to one Layal in a sloop of Antigua, and was then taken by Low and detained ever since, but never shared with them, and had about ten or twelve pounds when taken, which they gave him.

“Thomas Jones said he is a lad of about seventeen years of age, and was by Low and company taken out of Capt. Edwards at Newfoundland and kept by Low ever since.

“William Jones said, he was taken out of Capt. Ester at the Bay of Honduras the beginning of April last by Low and Lowther, and that he has been forced by Low to be with him ever since; that he never shared with them, nor signed the articles till compelled three weeks after he was taken, and the said Jones owned he had eleven pounds of the Quartermaster at one time, and eight pounds at another.

“Edward Eaton said, that he was taken by Low in the Bay of Honduras, about the beginning of March, and kept with him by force ever since.

“John Brown the tallest said that on the ninth of October last he was taken out of the Liverpool merchant at the Cape de Verde by Capt. Low who beat him black and blue to make him sign the articles, and from the Cape de Verde they cruised upon the coast of Brazil about eleven weeks, and from thence sailed to the West Indies, and he was on board of the Ranger at the taking of Welland.

“James Sprinkly said he was forced out of a ship at the Cape de Verde by Low in October last, and by him compelled to sign the articles, but never shared with them.

“John Brown the shortest said he was about seventeen years old, and in October last at the Cape de Verde was taken out of a ship by Low, and kept there ever since, and that the Quartermaster gave him about forty shillings, and other sailors aboard about three pounds.

“Joseph Sound said he was taken from Providence [at Bermuda] about three months ago by Low and company and detained by force ever since.

“Charles Church said he was taken out of the Sycamore galley at Cape de Verde, Capt. Scot commander, about seven or eight months ago, by Capt. Low, never shared, but the Quartermaster gave him about fourteen pounds.

“John Waters said he was taken by Low on the twenty-ninth of June last, out of [illegible] and they compelled him to take charge of a watch, and that he had thirteen pistols when taken, which was given him, and that he said at the time of the engagement with His Majesty’s ship they had better strike for they would have better quarter.

“Thomas Mumford, Indian, said he was a servant a fishing the last year and was taken out of a fishing sloop with five other Indians off of Nantucket by Low and company, and that they hanged two of the Indians at Cape Sables, and that he was kept by Low ever since and had about six bitts when taken.”

These excuses availed nothing except for Thomas Jones, the boy, and Thomas Mumford, the Indian. The rest were found guilty and duly sentenced.

The next morning John Kencate, the doctor on board the Ranger, was brought to trial. The Advocate General stated that although the prisoner “used no arms and was not harnessed (as they term it) but was a forced man, yet if he received part of their plunder and was not under a constraint, did at any time approve, or joined in their villainies, his guilt was at least equal to the rest. The Doctor being adored among them as the pirates for in him they chiefly confided for their cure and life, and in this trust and dependence it is, that they enterprise these horrid depredations not to be heightened by aggravation, or lessened by any excuse.”

“Capt. John Welland deposed, said that he saw the Doctor aboard the Ranger and that he seemed not to rejoice when he was taken but solitary. Capt. Welland was informed on board that the Doctor was a forced man and that he never signed the articles as he heard of.

“John Ackin, Mate, and John Mudd, Carpenter, swore they saw the prisoner at the bar walking forwards and backwards disconsolately on board the Ranger.

“Archibald Fisher, physician and surgeon on board the said Greyhound man-of-war, deposed that when the prisoner at the bar was taken and brought aboard the King’s ship he searched his medicines and the instruments and found but very few medicines and the instruments were very mean and bad.”

Others testified that the doctor was forced on board, by Low, and that he never signed articles so far as they knew or heard, but used to spend much of his time in reading, and was very courteous to the prisoners taken by Low and his company, and that he never shared with them.

The doctor himself said that he was surgeon of the Sycamore galley, Andrew Scot master, and was taken out of that ship in September last at Bona Vista, one of the Cape de Verde islands, by Low and Company, who detained him ever since, and that he never shared with them, nor signed their articles.

The Court then cleared the doctor and proceeded with the trial of Thomas Powell, Joseph Sweetser and Joseph Libbey. The name of the latter is not found in the first published lists of the pirates gaoled at Newport for the reason that he was one of those detained by Captain Harris in hopes of capturing Low who had deliberately deserted them when jointly they probably could have taken the man-of-war. Libbey’s name appears in the published lists of those condemned and executed as having been born in Marblehead.

At the trial of these men Doctor Kencate testified that “he well knew Thomas Powell, Joseph Sweetser and John Libbey, and that Thomas Powell acted as gunner on board the Ranger, and that he went on board several vessels taken by Low and company, and plundered, and that Joseph Libbey was an active man on board the Ranger and used to go on board vessels they took and plundered and that he saw him fire several times. The Doctor further deposed that Joseph Sweetser now prisoner at the bar was on board the pirate Low and that he had seen him armed but never saw him use the arms and that the said Sweetser used to often get alone by himself from amongst the rest of the crew, he was melancholy and refused to go on board any vessel taken by them and got out of their way. And the deponent further said that on that day, as they engaged the man-of-war, Low proposed to attack the man-of-war first by firing his great guns then a volley of small arms, heaving in their powder flasks and board her in his sloop, and the Ranger to board over the Fortune, and that no one on board the Ranger disagreed to it as he knows of, for most approved of it by words and the others were silent.

“Thomas Jones deposed that Thomas Powell acted as gunner on board the Ranger, and Joseph Libbey was a stirring, active man among them, and used to go aboard vessels to plunder, and that Joseph Sweetser was very dull aboard, and at Cape Antonio he cried to Dunwell to let him go ashore, who refused, and asked him to drink a dram, but Sweetser went down into the hold and cried a good part of the day, and that Low refused to let him go, but brought him and tied him to the mast and threatened to whip him; and he saw him armed but never saw him use his arms as he knows of, and that Sweetser was sick when they engaged the man-of-war, though he assisted in rowing the vessel.

“John Wilson deposed that Thomas Powell was gunner of the Ranger and the Sabbath day before they were taken the said Powell told the deponent he wished he was ashore at Long Island, and they went to the head of the mast and Powell said to him I wish you and I were both ashore here stark naked.

“Thomas Mumford, Indian, not speaking good English, Abissai Folger was sworn as interpreter, deposed that Thomas Powell, Joseph Libbey and Joseph Sweetser were all on board of Low the pirate, that he saw Powell have a gun when they took the vessels, but never saw him fire, he saw him go on board of a vessel once, but brought nothing from her as he saw. He saw him once shoot a negro but never a white man. And he saw Joseph Libbey once go aboard a vessel by them taken and brought away from her one pair of stockings. And that Joseph Sweetser cooked it on board with him sometime, and sometimes they made him handle the sails. Once he saw said Sweetser clean a gun, but not fire it, and Sweetser once told him that he wanted to get ashore from among them, and said he if the man-of-war should take them they would hang him, and in the engagement with the man-of-war, Sweetser sat unarmed in the range of the sloop’s mast, and some little time before the said engagement he asked Low to let him have his liberty and go ashore but was refused.”

There was other testimony to much the same effect. Powell said he was taken by Lowther in the Bay of Honduras in the winter of 1721-2 and by him turned over to Low. Libbey said he was a forced man and produced a newspaper advertisement in proof. Sweetser said he was taken by Lowther about a year before and forced on board of Low. He too produced an advertisement to prove that he had been forced. Powell and Libbey were found guilty and Sweetser was cleared.

Hazel, Bright, Fletcher, and Child and Cunningham, who had all been detained on board the Greyhound in the latter’s pursuit of Low, were then placed on trial. By numerous witnesses it was shown that all had been active on board the Ranger at the time of the fight but that Fletcher was only a boy and that Child had come on board from the Fortune only three or four days before the fight. Captain Welland spoke a good word for Cunningham and said that he had got him water and brought the doctor at the time he was laying bleeding below hatches for nearly three hours with a sentinel over him. John Bright was the drummer and “beat upon his drum upon the round house in the engagement.”

Thomas Hazel said he had been forced by Low about twelve months before in the Bay of Honduras. Bright said that he was a servant to one Hester in the Bay and had been taken by Low about four months before and forced away to be his drummer.

Cunningham said he had been forced about a year before from a fishing schooner and that he had tried to get away at Newfoundland but without success. Fletcher, the boy, said he had been forced by Low from on board the Sycamore galley, Scot master, at Bona Vista, because he could play a violin. There is no record of what Child had to say for himself. Fletcher and Child were found not guilty; the others were sentenced to be hanged. Cunningham and John Brown “the shortest” were recommended “unto His Majesty, for Remission.”

While the pirates were in prison and especially in the interim between their condemnation and execution they were visited frequently by the ministers who afterwards stated that “while they were in prison, most seemed willing to be advised about the affairs of their souls.” John Brown penned in writing a “warning” to young people in which he declared “it was with the greatest reluctance and horror mind and conscience, I was compelled to go with them . . . and I can say my heart and mind never joined in those horrid robberies, conflagrations and cruelties committed.” On the day before they were executed letters were written by many of them to relatives and Fitzgerald composed a poem which afterwards was printed.

The gallows were set up between high and low water mark on a point of land projecting into the harbor, then and now known as Gravelly Point. At that time there was no street or way that gave direct or convenient access and the crowds that gathered to witness the execution went around by what afterwards was known as Walnut Street by the almshouse, or filled the boats and small vessels that lined the shore. Most of the condemned had something to say when on the gallows usually advising all people, especially young persons, to beware of the sins that had brought them to such an unhappy state. The execution took place on July 19, 1723, between twelve and one o’clock, and twenty-six men were “hanged by the neck until dead” in accordance with the sentence of the Court.

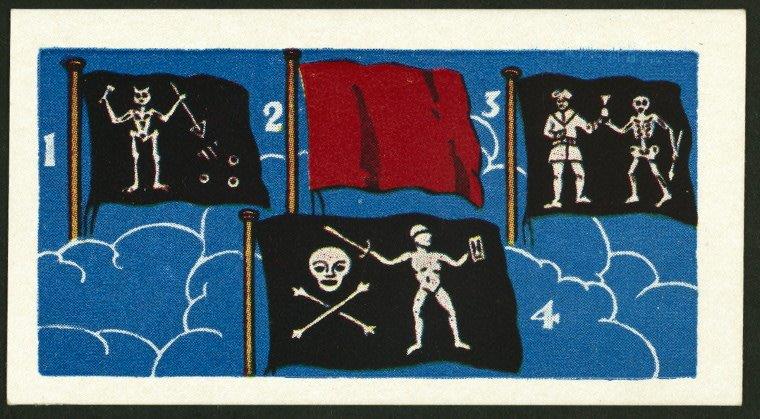

“Mr. Bass went to prayer with them and some little time after the Rev. Mr. Clap concluded with a short exhortation to them. Their Black Flag, with the portrait of death having an hourglass in one hand, and a dart in the other, at the end of which was the form of a heart with three drops of blood falling from it, was affixed at one corner of the gallows. This Flag they called ‘Old Roger’ and often used to say they would live and die under it.

“Never was there a more doleful sight in all this land than while they were standing on the stage waiting for the stopping of their breath and the flying of their souls into the Eternal World. And oh! How awful the noise of their dying moans!”

The bodies were not gibbetted but taken to Goat Island (also called Fort Island) and buried on the shore between the high and low water marks.

After the execution had taken place, Captain Solgard set sail in the Greyhound for his station at New York, taking with him the pirate sloop. His exploit was looked upon as a great service rendered to the country and the merchants of New York were anxious that some public acknowledgment be made, and so it came about that the Common Council of the City, at a meeting held July 25, 1723, passed an order presenting to Captain Solgard the Freedom of the City and providing that the seal of the Freedom be enclosed in a gold box, the Arms of the Corporation to be engraved on one side and a representation of the engagement on the other, with this motto: Quaesitos Humani Generis Hostes Debellare Super-bum 10 Junii 1723. The clerk was instructed to have the Freedom of the City handsomely engrossed on parchment and when ready the Council voted to wait upon Captain Solgard in a body and present the same.

[Banner image: Pirates leading captives to a boat, with buildings burning in the background. Artist unknown. (New York Public Library)]