This is the story of the Reverend James Manning, Brown’s first president, his wife Margaret, and Lewis Manning, his slave. The manumission of Lewis Manning in 1784 is important for two reasons. First, it complicates Brown University’s stories about slavery on campus by proving that enslaved people were present for longer than was previously assumed. Second, because we know a little about what happened to Lewis Manning, it illuminates our understanding of the problems faced by the free Black community in late eighteenth-century Providence.

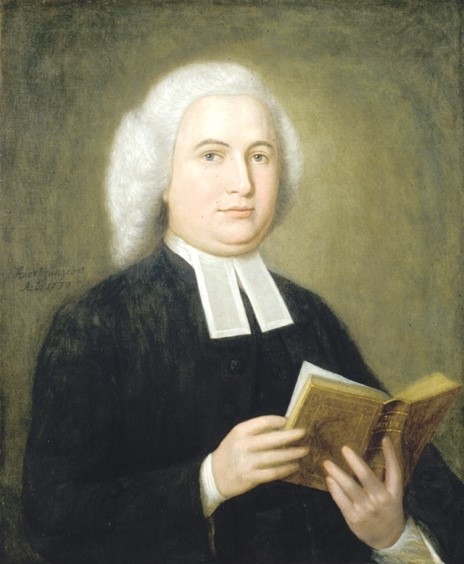

James Manning (1738-1791) painted in 1770 by Scots artist Cosmo Alexander. Manning was thirty-two and already showing signs of a double chin (Brown University Portrait Collection)

On August 2, 1784, James Manning, President of Rhode Island College (later renamed Brown University), left his house on the college grounds, and walked down what is now College Hill to a meeting of the Providence Town Council. It was almost certainly a hot day—August in Providence can be unpleasantly warm. Manning, who was considerably overweight (when he died seven years later he weighed upwards of three hundred pounds) probably found the walk less than pleasant, and the walk back up the steep hill even worse.[1] He took with him a thirty-year-old Black man called Lewis Manning, one of several enslaved people who had lived and worked on campus for up to twenty years.

Why did Manning free this man? He had no moral objection to slavery, as the 1790 census shows him as still having two slaves in his household. Many of the important members of the College’s Corporation opposed slavery, but others did not. Some, like John Brown and Cyprian Sterry of Providence, were still active in the African slave trade. At the time Manning walked down College Hill to manumit Lewis Manning, the Providence Abolition Society was still but a gleam in Moses Brown’s eye. It would be founded in 1789.[2]

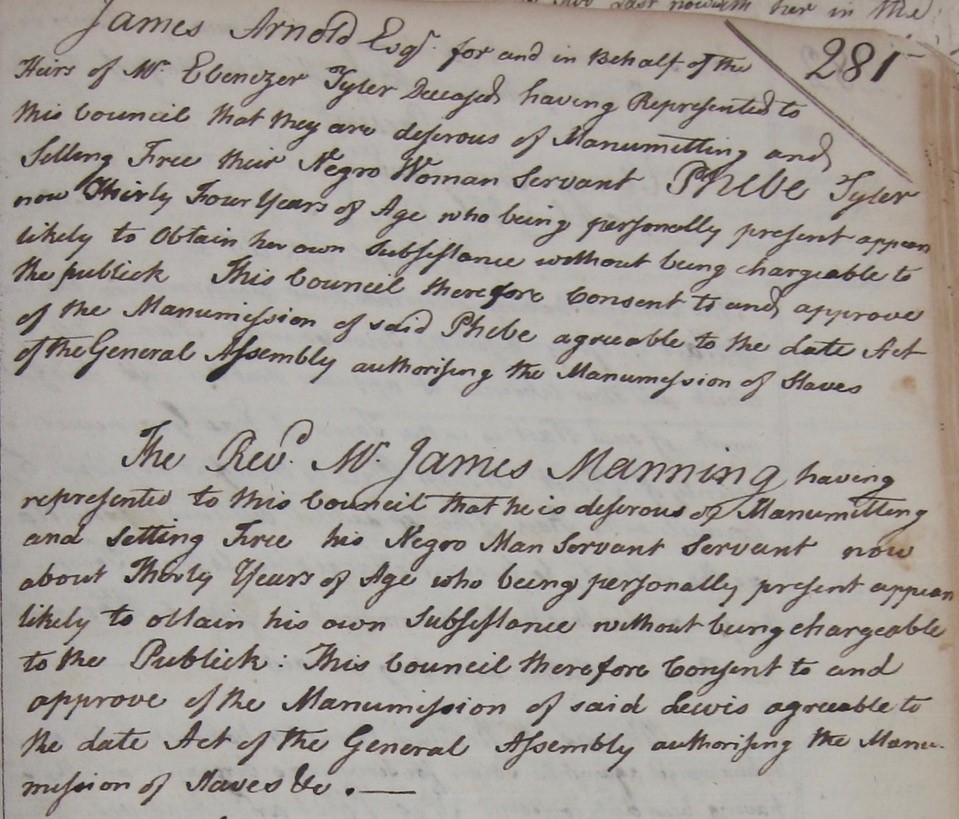

It’s possible that Manning freed the man because by 1784, after the end of the Revolutionary War, many other Rhode Island slaveholders were freeing their “servants” (or not pursuing them if they ran away and freed themselves). Unlike earlier manumissions, which often involved little more than a signature on a piece of paper declaring the holder free, later manumissions had to be made official. The Black person about to be freed had to be inspected by Town Council members, charged with judging whether the person was capable of supporting himself or herself, or whether he or she might end up in the workhouse or otherwise become a drain on public funds. Lewis Manning, as with other enslaved people whom their owners wanted to free, had to appear fit and able and self-sufficient. Owners were discouraged and sometimes even forbidden to rid themselves of the sick, the old, and the lame; the assumption was that owners should not expect local taxpayers to support their cast-offs.

Perhaps Lewis Manning had persuaded his owner that he wanted to be free.

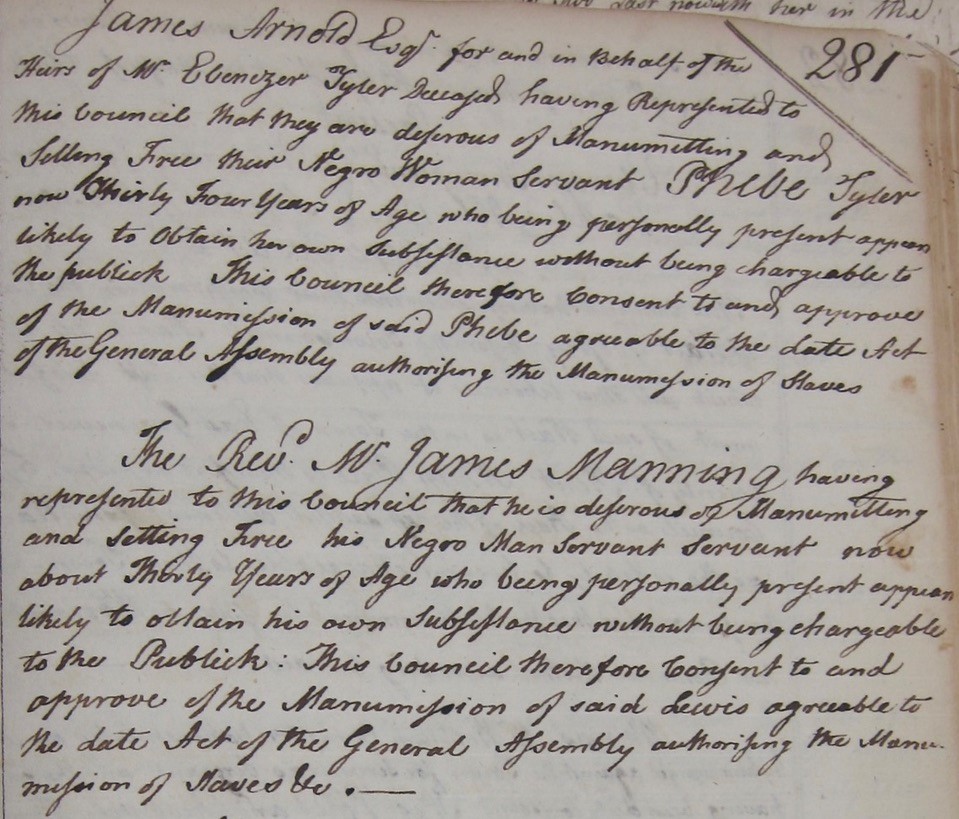

There were two nervous Black people waiting to be judged by the Town Council that August day. First was thirty-four-year-old Phebe Tyler, whose master had died. She was presented to the Town Council and judged unlikely “to be charged to the Publick.” Clearing her last obstacle, she became free.

The Providence Town Council members looked at Lewis Manning and concluded that, like Phebe, he was “likely to obtain his own Subsistence without being chargeable to the Publick.” They added that they consented to and approved the “manumission of said Lewis agreeable to the late Act of the General Assembly authorizing the Manumission of Slaves &c.”[3]

The legislation they were referring to was “An Act for the Manumission of Negroes, Mulattoes and others and for the gradual Abolition of Slavery,” which went into effect on March 1, 1784.[4] The Act began grandly, declaring that “Whereas all Men are entitled to Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness, and the holding of Mankind in a State of Slavery . . . is repugnant to this Principle, and subversive to the Happiness of Mankind . . . .” The law let slaveholders off the hook for their freedmen’s future needs, by providing that if the person freed was under forty years of age and of “sound body and mind, which shall be judged and determined by the Town-Councils,” such person could later be “supported as other paupers and not at the separate Expense of the Claimants [i.e., the former slave owners] if they become chargeable.”[5]

Manumission of Phebe Tyler and Lewis Manning from Providence Town Council Records, vol. 5, p. 281, August 2, 1784 (Photograph by Jane Lancaster)

The adjective “gradual” in the title of the Act indicated, however, that no enslaved person was immediately freed. Male children born to an enslaved mother would be freed when they were twenty-one, and female children would be freed when they were eighteen. Accordingly, the Act did not free Lewis Manning or provide for his emancipation in the future. (Slavery was not finally outlawed in Rhode Island until 1842.) Yet emancipation was in the air, and by 1790 more than three-quarters of Rhode Island’s Black residents were free.[6]

Early in the twenty-first century Brown University’s eighteenth president, Ruth Simmons, charged a team of scholars to investigate the university’s connections with slavery and the African slave trade. Rhode Islanders dominated the North American share of the African slave trade, launching over a thousand slaving voyages in the century before the abolition of the trade in 1808, and scores of illegal voyages thereafter. Small time investors such as tradesmen and genteel widows also sent cargo such as textiles, hoping for a return when the goods were sold in return for Africans, and the enslaved people were sold in the New World. [7]

Less well-documented was Brown University’s involvement in slavery and the slave trade. Some of these connections were described in a short volume entitled the Report of the Slavery and Justice Committee.[8] Published in 2007, the Report lays out in detail the disastrous voyage of the slave ship Sally, which sailed from Providence in 1764, the year Brown University was founded. Almost half the captured slaves died before, during or immediately after the voyage across the Atlantic: out of 196 Africans purchased, only 108 were sold in Antigua. Most of those who died passed away from diseases, but a handful were shot during an attempted uprising at sea. The survivors were in such an emaciated state that some sold for as little as £5, whereas a prime slave could fetch £50. The Sally was owned by the four Brown brothers—John, Moses, Nicholas and Joseph—who were among the principal sponsors and supporters of the new college (years later, after the son of Nicholas donated money, the college was renamed Brown). The Sally was commanded by Esek Hopkins, whose clock then sat in the office in University Hall where more than two centuries later the Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice held its meetings. Captain Hopkins was brother of Stephen Hopkins, several times a governor of Rhode Island, who would shortly become the college’s first chancellor and later sign the Declaration of Independence.[9]

The Report also described the contributions of enslaved labor to the new college. After moving to Providence from Warren in 1770, the college needed a building, and many local people helped pay for it. Records show that rather than giving cash, some benefactors sent their enslaved people to assist in the construction. The Report mentions three or possibly four enslaved men who worked on the college’s magnificent new building, the College Edifice (now University Hall). Their wages of fifty cents a day, the going rate for laborers, went to their owners. Thus, the earnings of “Earle’s Negro,” “Henry Paget’s Negro,” “Mary Young’s negro man,” and (possibly) “Martha Smith’s Abraham,” allowed Mr. Earle, Mr. Paget, Mrs. Young and Mrs. Smith to contribute to the building fund. Those four men worked for almost one-third of the time the building was being erected—61 days compared with about 100 days by free laborers. Some of those free laborers were Black or Indian men. William Mingo had a regular work contract but was paid at least double for his efforts “over and above his common wages and agreement,” especially when he was digging the thirty-foot well, as did Job “an Indian” who also received an extra six shillings for his work on the well.[10]

Meanwhile, laborers were also building a house for James Manning, the college’s president. It was situated a little to the north east of the College Edifice, near where the Carrie Tower stands on what is now called the Quiet Green. Perhaps ironically, it was not far from the memorial to Brown’s slavery past, a ball and chain sunk into the ground. Etched on a nearby stone are the words: “This memorial recognizes Brown University’s connection to the trans-Atlantic slave trade and the work of Africans and African-Americans, enslaved and free, who helped build our university, Rhode Island, and the nation.”[11] But this marker fails to acknowledge that Manning, his wife Margaret, and their servants, enslaved and free, lived nearby until James Manning died in 1791.[12].

The Slavery and Justice Report states (on page 18), “If any contemporaries were surprised or troubled when the school’s first president, Rev. James Manning, arrived in Rhode Island accompanied by a personal slave, they never seem to have said so publicly.” The report then added in parentheses the important but erroneous claim: “(Manning manumitted the man in 1770, shortly before the college moved to its current site in 1770).”

This claim was a mistake copied from earlier secondary sources.[13] Evidence from the 1774 Providence census, the 1790 Federal census, the 1791 Providence census, and the Providence Town Papers proves it to be false. Manning had enslaved people residing and/or working on campus at least between 1774 and 1790.[14]

While it is possible Manning did free one personal slave before he and the college moved from Warren to Providence, manumission records are sketchy and none was found confirming this event. In any case, Manning soon acquired other Black servants (the usage of “Black servant” was often a euphemism for an enslaved person), and by the time the town of Providence carried out a census in 1774, he had three Black people working in his household. The 1774 census did not differentiate between enslaved and free, but the likelihood of his having three free Blacks in his household at that time is small. According to the 1790 federal census, which did distinguish between slaves and free persons, two of the college’s five Black servants were enslaved.[15]

The Revolutionary War adversely affected Manning’s income, which depended to some extent on student fees. After a British army invaded and occupied Newport and the rest of Aquidneck Island in early December 1776, Rhode Island’s state artillery regiment was billeted in the College Edifice, the students were sent home, and the College was closed. The British army stayed at Newport for almost three and a half years, posing a constant threat of invading Providence. After the British evacuated Newport in October 1779, the Americans redeployed their troops. Manning must have breathed a sigh of relief when the Council of War effectively handed his College back to him. On April 29, 1780, he advertised in the Providence Gazette, announcing that the college would reopen on May 10. His optimism was premature, however, and his hopes were dashed when on June 25, 1780, the French army, America’s allies and now occupying Newport, seized the College Edifice for use as a military hospital. The college was lost again and four hundred French troops suffering from scurvy and other diseases caught on their Atlantic crossing were housed there.

Ezra Stiles, former Newport Congregationalist minister, and since 1778 President of Yale College, was visiting in Rhode Island in 1780 and wrote that he was pleasantly surprised by the Frenchmen he met, noting that “neither Officers nor men are the effeminate Beings we were heretofore taught to believe them.”[16] Effeminate or not, they did a lot of damage and when the French finally left Providence on May 27, 1782, the College Edifice was in a horrible state. As Manning wrote to an English friend, it “was occupied by a crude and wasting soldiery, first for barracks and then for a hospital, until they threatened its almost total demolition.”[17]

Two of Manning’s Black “servants” had disappeared by 1776. With the college closed, there was no need for them, as part of their job was cooking and cleaning for the students. The Mannings kept one Black male over the age of sixteen. If, as seems possible, he was Lewis Manning, he was then about twenty-two years of age. He would have been required to perform all types of work, as cook, coachman, gardener, whatever needed to be done. By 1790, when the college was functioning again and more labor was needed, the federal census shows that the Manning household included three non-white free persons and two enslaved people. One year later, at the time of James Manning’s death, he had no enslaved people but did have two free Blacks living in his household.[18]

Neither James Manning nor his former slave, Lewis Manning, survived long.

The Reverend James Manning, who as previously noted was grossly overweight, had a sudden “apoplexy,” a heart attack or a stroke, in July 1791 and died five days later.[19] He was only fifty-three. His widow stayed in the house for a few months then moved elsewhere in Providence and lived on for a further quarter century surrounded by friends and family, a comfortable member of Providence’s Baptist society. Her nephew, the Reverend Stephen Gano (1762-1828), arrived in Providence in 1792 and replaced James Manning as pastor of the First Baptist Church.

Lewis Manning’s freedom was short-lived and he did not long survive his former master. His living conditions were likely inferior to his experiences in the Mannings’ attic. The 1790 census reveals him as head of a household of three free Blacks living in a low-lying, swampy area of stinking tanneries, small houses and brothels near Charles Street in Providence. The only neighbor of color on the same page of the census is Cato Coggeshall, who formerly lived in Newport. One of Cato’s claims to fame is a mention in a letter from poet Phyllis Wheatley.[20] Cato, who was literate, and an activist in the Free African Union Society, lived in a household of five free Blacks, possibly including his children.[21] Otherwise Lewis’s neighbors were poor whites, trying to scrape up a living. The area became known as Hard Scrabble, descriptive of the difficult lives of its inhabitants. Perhaps Lewis had a wife and a child, or perhaps he was simply sharing a lodging with other members of Providence’s free Black population, which had risen dramatically after the war. The postwar economic recession affected almost everyone, especially the poor Black population as well as poor whites. In the late 1780s and early 1790s jobs were scarce.

It is not known what Lewis did for a living once he was free. As a thirty-year-old man, presumably in good health, who had been a household servant, and possibly literate, he was probably not well suited for heavy manual labor. He was a bit old for starting to go to sea, which was a common occupation for free Black men. Some Black men were barbers and carters, others were waiters and day laborers, some were cooks and gardeners, and yet others were proprietors of small businesses. Some free Blacks prospered, but many did not.

Whatever Lewis Manning did, he survived only a decade as a free man. By the time he was forty he was ill, unable to work and reliant on support from the town of Providence. By April 1794 he was dead and buried, probably in an unmarked grave in the pauper plot at North Burial Ground, not far from where his former master rested in a large marble tomb. A carpenter submitted an account for twelve shillings “making a coffin for Lewis Manning a poor Black man maintained in his Sickness by said Town.”[22]

Although Margaret Stites Manning had no children of her own she was great-aunt to the children of her niece Margaret Holroyd. There is no evidence that she did anything to help the man her husband had formerly enslaved. She lived comfortably with a steady income from bank dividends, surrounded by mahogany furniture and silver spoons, creamers, and mustard pots. When she died in 1815 her estate was valued at $1,586.34, which in current values represents almost a million dollars in terms of relative income.[23] There is no evidence Lewis Manning left anything.

Margaret Stites Manning (1740-1814) painted in 1770 by Scots artist Cosmo Alexander (Brown University Portrait Collection)

[1] For Manning’s weight, see the item for Manning, James in Encyclopedia Brunoniana (2003), quoting Reuben Guild, The Early History of Brown University, Including the Life, Times, and Correspondence of President Manning (Providence: Snow and Farnham, 1897); https://www.brown.edu/Administration/News_Bureau/Databases/Encyclopedia/search.php?serial=M0100

[2] Works on slavery and abolition in New England include Joanne Pope Melish, Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and “Race” in New England (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1998), and John Wood Sweet, Bodies Politic: Negotiating Race in the American North 1730-1830 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003).

[3] https://sosri.access.preservica.com/uncategorized/digitalFile_cb907aee-887d-4c77-9cdd-88ac56b0ec9c/

[4] Acts and Resolves of Rhode Island, Feb. 1784-Dec. 1786, vol. X, 6-7.

[5] The forty-year age limit was changed to thirty in October 1785—perhaps because too many worn out former slaves were being supported by the public purse.

[6] According to the first Federal census in 1790, in Rhode Island 958 people were still enslaved, while there were 3,484 free non-whites. https://userpages.umbc.edu/~bouton/History407/SlaveStats.htm; Heads of Families at the First Census of the United States Taken in the Year 1790, Rhode Island (Bureau of Census, ed.) (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1908).

[7] Rachel Chernos Lin, “The Rhode Island Slave-Traders: Butchers, Bakers and Candlestick-Makers,” Slavery & Abolition 23:3 (2002), 21-38.

[8] Slavery and Justice: Report of Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice (Providence: Brown University, 2007); see also http://brown.edu/Research/Slavery_Justice/report/, which also provides access to images of many relevant original documents.

[9] For a database on the slave trade, which includes information on Rhode Island ship owners and captains, see David Eltis et. al. (eds.), The Transatlantic Slave Trade: A Database on CD-ROM (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999) or an updated version at www.slavevoyages.org. The authoritative work on the Rhode Island slave trade was written by Jay Coughtry a quarter century earlier than the Slavery and Justice Report. See Jay Coughtry, The Notorious Triangle: Rhode Island and the African Slave Trade 1700-1807 (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1982).

[10] Robert P. Emlen, “Slave Labor at the College Edifice: Building Brown University’s University Hall in 1770,” Rhode Island History, vol. 66 no. 2, p. 38; Brown Daily Herald, online article at https://www.browndailyherald.com/2006/04/19/university-hall-construction-records-show-us-nuanced-ties-to-slavery-2/

[11] See online Brown University article at https://www.brown.edu/about/public-art/martin-puryear-slavery-memorial. The memorial was unveiled in 2014.

[12] The next president, Jonathan Maxcy, had one “other free person,” that is, other than white, living in his house at the time of the 1800 federal census. 1800; Census Place: Providence, Providence, Rhode Island; Series: M32; Roll: 45; Page: 216; Image: 428; Family History Library Film: 218680.

[13] Slavery is not mentioned in W.C. Bronson, The History of Brown University 1764-1914 (Providence: Brown University, 1914) , or in Reuben Aldridge Guild, Life, Times, and Correspondence of James Manning (Boston, MA: Gould and Wilson, 1864). Accordingly, it is unclear where this idea originated, apart from the fact it made Manning look good.

[14] 1791 Census of Providence, Providence Census Collection, Mss 214, sg 6, vol. 1 (accessed from ancestry.com).

[15]John R. Bartlett, Census of the Inhabitants of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, 1774 (Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1969), 46. See also the 1790 Federal Census, Providence Rhode Island, Roll M637_10, page 183; Image: 114; Family History Library Film: 0568150, which shows Manning with a household of 60 boys (the students), three non-white free persons and two slaves. The 1791 census of Providence shows him with no slaves, but with two free Blacks residing in his household. 1791 Census of the Town of Providence, Providence Census Collection, Mss 214, sg 6, vol. 1, Rhode Island Historical Society. The manumission document, dated August 3, 1784, is in the Providence Town Council Records, vol. 5, 281, Providence City Hall. I am immensely grateful to Cherry Fletcher Bamberg for pointing me to this census information.

[16]Journal Entry, May 22, 1780, in Franklin B. Dexter, ed., The Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles D.D, LL.D., vol. 2 (New York: Charles Slocum Co., 1901), 22.

[17] James Manning to Reverend Benjamin Wallin, May 23, 1783, in Guild, Manning, 293.

[18] See footnote 5.

[19] See online Brown University article at https://www.brown.edu/Administration/News_Bureau/Databases/Encyclopedia/search.php?serial=M0100

[20] Tara Bynum, “Cesar Lyndon’s Lists, Letters, and a Pig Roast,” Early American Literature, vol. 53, no. 3 (2018), 839-849.

[21] Konstantin Dierks, “‘Let Me Chat a Little’: Letter Writing in Rhode Island before the Revolution,” Rhode Island History, vol. 53 no. 4 (Nov. 1995), 129. According to The Free African American Cultural Landscape: Newport, RI, 1774-1826, by Akeia A.F. Benard (Storrs, CT: University of Connecticut, 2008), which can be accessed at http://www.ripnewport.com/Dr.%20Benard%20directory.pdf,

Cato and his four children, slaves of Deacon Nathaniel Coggeshall (1702-1784), were admitted to Newport’s First Congregational Church in 1771. Perhaps they were freed on Coggeshall’s death.

[22] Providence Town Council Records, vol. 5, 281, City Hall, Providence; Report of the Brown Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice, online article at http://brown.edu/Research/Slavery_Justice/report/ accessed April 3, 2013, 12.

[23] Providence RI Wills and Probate Index, vol. 12, 56-59 (accessed from ancestry.com). Because the bulk of the estate was left to minor great-nephews and nieces, probate of the estate was delayed until each reached twenty-one, by which time the value of the estate had considerably increased. For the relative value of the estate in 1815, see Measuring Worth https://www.measuringworth.com/calculators/uscompare/relativevalue.php