Rhode Island has an extensive immigrant history. Evelyn Savidge Sterne’s Ballots and Bibles: Ethnic Politics and the Catholic Church in Providence is a comprehensive story about the discrimination Irish, French Canadian, and Italian immigrants faced in Rhode Island. Although the three groups comprise the majority of Rhode Island immigrant groups, one story of Rhode Island immigrant discrimination has been left out: the experience of Providence’s Chinatown residents. It can be a surprise to many that Providence once even had a Chinatown.

Providence’s first Chinatown started on Burrill Street around the late 1800s. Around 1900, the Chinese migrated to Empire Street, which became the new Chinatown. The migration was caused by the construction of a theater on Westminster Street and the demolition of a tenement house on Chapel Street.[1]

Providence’s Chinatown was always small. By 1920, Providence’s Chinatown numbered only 300 people.[2] By 1932, Rhode Island’s total Chinese population, scattered throughout Providence, Central Falls, Pawtucket, Woonsocket, and Westerly, numbered only 600.[3]

Providence’s Chinatown was characterized by laundries and restaurants patronized by white people. The reason Chinese were relegated to these businesses, as they were throughout the country, was a combination of racial hostility against Asians, competition with white Americans, and immigration law.

The early 1900s was a period of intense discrimination against Chinese immigrants nationally. The prejudiced views of Chinese by the white establishment made many employers hesitant to hire Chinese workers in decent jobs. Many white Americans believed that the Chinese as a race thrived in a dirty and overcrowded atmosphere similar to a den of rats. Indeed, many White Americans actually believed or at least debated whether the Chinese ate rats.[4] Another stereotype was that the Chinese were addicted to gambling and opium. According to many at the time, most of the few Chinese women in the United States were prostitutes, and Chinese men were predators of white women. In summary, in the words of a historian of New York’s Chinatown, the Chinese were seen as “inferior, dishonest, immoral, indecent, unsanitary, and disease-ridden.”[5]

Restaurants and laundries filled a niche demand in the economy. These business choices generally did not place Chinese in competition with white workers and white businesses.

Interior of typical Chinese restaurant. “Chinese Population is 198,” Providence Journal, February 2, 1906, 14.

Immigration law was the third factor for the dominance of restaurants and laundries among Chinese-owned businesses. In 1882, Congress enacted the Chinese Exclusion Act, which barred almost all Chinese immigration to the United States until 1943, when the law was repealed. Most Chinese immigrants were stuck in the United States because if they returned to China, they could not return. There was, however, an exception in the Exclusion Act for merchants and students. As a result, many Chinese established restaurants and laundries to classify themselves as merchants, thus allowing them to travel freely between the United States and China.

Kitchen of a Chinese Restaurant. “Chinese Population is 198,” Providence Journal, February 2, 1906, 14.

Most Chinese in America shared the background of a poor male farmer in the Guangdong region. Around 1850, word reached Guangdong province that there was a “Gold Mountain” in the United States. Gold Mountain referred to California, the home of the great gold rush that started in 1849. Many Chinese were desperate to find anything that could improve their isolated and destitute lives. In many cases, the male head of the family decided to go to California, get “rich quick,” send remittances home, and eventually earn enough to return to his family in China. For most Chinese immigrants, this plan would be disrupted by the reality of economic conditions in the United States and restrictive immigration laws that kept them stuck and prevented their families from following them.

Before the 1870s, very few Chinese resided in the eastern part of the United States. The increasing violence and discrimination in the West drove many Chinese to move east of the Rocky Mountains. New York City’s Chinese population steadily rose, from 29 in 1870, to 2,935 in 1890, and to 7,000 in 1900.[6] The Chinese east of the Rocky Mountains ended up forming Chinatowns in cities, in Boston, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, New York City, Chicago, St. Louis, New Haven, . . . and Providence. These Chinatowns had very similar characteristics to those in the West, such as crowded boarding houses, economic insecurity, and a lot of restaurants and laundries. Circumstances were better east of the Rocky Mountains than west, but there was still prejudice against the Chinese in the East, and city governments were not hesitant to pass discriminatory ordinances.

An example of mob violence in the West occurred in what would be called the Rock Springs Massacre. Rock Springs was a mining community established by the Union Pacific Railroad Company in Wyoming. In 1875, the company brought in 150 Chinese workers to break a strike by the white miners. By September 1885, the company employed 150 white miners and 331 Chinese miners.[7] White miners believed that Chinese miners would eventually permanently replace them. On September 2, 1885, an armed group of 150 miners entered Rock Springs’ Chinatown. They shot at anything that moved and burned the Chinatown to the ground. A total of 28 Chinese were killed and 15 were wounded. Nine bodies were found burned.[8]

California and other western states passed many discriminatory laws aimed at the Chinese to satisfy the white electorate. California segregated its public school system by setting up separate schools for Chinese children. It got even worse between 1871 and 1885 when new state legislation gave the legal right to school systems to shut down the segregated schools of Asians.[9]

In 1870, the city of San Francisco passed an ordinance to attack the Chinese laundry industry. The ordinance required laundries with a horse-drawn vehicle to pay a license fee of $2 per quarter, those with two horse-drawn vehicles to pay $4 per quarter, and those with no vehicles at all to pay $15 per quarter. This ordinance clearly targeted Chinese laundries, since most of them delivered on foot. In addition to legislation, the California state supreme court in 1854 ruled that Chinese were not allowed to testify against whites. The threat of being caught while perpetrating anti-Chinese violence was thus virtually eliminated. In 1879, California adopted a new constitution, which contained the following shocking provision: “[A]ny officer, director, manager, member, stockholder, clerk, agent, servant, attorney, employee, assignee, or contractor of any corporation … who shall employ in any manner or capacity … any Chinese or Mongolian is guilty of a misdemeanor.”[10]

Interior of a Chinese store. “A ‘New China’ Here Too,” Providence Journal, February 16, 1913, Section 5, 5.

On the national level, a Chinese immigrant could never become a citizen and gain the rights and privileges of being one. The 1790 Naturalization Act said that only “free white persons” could be naturalized. So all Chinese immigrants were barred from becoming citizens. The children of Chinese immigrants born in the United States were guaranteed citizenship through the 14th Amendment, but because of widespread prejudice and the institutionalization of it, Chinese American citizens saw few benefits from their citizenship status.

The residents of Providence’s Chinatown faced unpredictable discrimination. White residents could be supportive of the Chinese in one moment and hostile toward them in another moment.

An 1899 article in the Providence Journal described how a resolution was brought up in the Providence Common Council calling for an ordinance prohibiting the Chinese from receiving restaurant licenses. The resolution failed to receive widespread support. The police chief of Providence stated:

You might just as well try to pass an ordinance prohibiting a naturalized Irishman keeping a saloon … The Chinese have the same right to keep restaurants, providing they are decent about it and do not disobey the law, as citizens of any other nationality. To attempt to prohibit them in the manner suggested would be class legislation of the worst sort.

The police chief continued by saying that “the circumstances in the case do not warrant action against the Chinese restaurant keepers” for the simple reason that he had never heard a word of complaint against a Chinese restaurant. To reassure his listeners, the police chief stated that whenever he received a restaurant license application from a Chinese person, he purposely held it back two or three months so he could make a “strict evaluation” of the character of the Chinese applicant.[11] If the police chief’s views reflected those of Providence’s white population, then the Chinese had decent support, although it was telling that the police chief felt comfortable admitting that he purposely delayed the granting of restaurant licenses when the applicants were Chinese. This was nothing other than a discriminatory act that could have created severe financial difficulties if a Chinese person depended on establishing a restaurant in a timely manner to support his or her family.

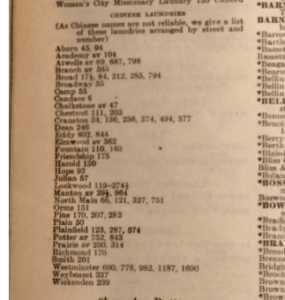

Another instance of business discrimination was how Chinese businesses were listed in the 1910 Providence Business Directory. The Directory listed businesses by type and owner’s name. But the Directory lists the 63 Chinese laundries by street name and number only. The section for Chinese laundries justified this choice with the following explanation: “As Chinese names are not reliable, we give a list of these laundries arranged by street and number.”[12] One wonders if the Directory’s authors were too lazy to determine how to spell Chinese names. The listing of Chinese businesses is another instance where white sentiment towards the Chinese was positive in some ways, but it came with a dose of unpredictable discrimination too.

“As Chinese names are not reliable, we give a list of these laundries by street and number.” 1910 Providence Business Directory. 1910 Providence Business Directory, 744, accessed Rhode Island State Archives.

A 1906 article in the Providence Journal described how white sentiment for the Chinese was favorable at that particular time. The article recounted a time when a Chinese person filed a restaurant application to the Board of Aldermen. Some members of the Board refused to approve such an application because they believed that the restaurant would be a “den of iniquity” where the “principal orders would be for opium pipes.” Luckily “the church people” came to the defense of the Chinese applicants, and the Chinese generally and applications were approved. The article said that at first, white people were afraid of the Chinese restaurants because “of prejudice based upon the assumption that rodents entered largely into the composition of the dishes served.” Eventually “the bridge had been crossed and the excellence of the cuisine was understood and appreciated.” The article gave further positive sentiment toward the Chinese when it bemoaned the immigration process the Chinese faced:

Outpourings from countries where anarchy sways, where sedition is rampant and crime is almost unchecked, come and go at will, while the Chinese, who, according to the local police record, have done nothing worse than play fan-tan and dominoes on Sunday – and there are few who have thus been complained of – are forbidden to enter and almost prohibited from departing under penalty of never again seeing their friends here.[13]

Although white sentiment had so far proven to be largely positive, it was fickle and in a moment it could quickly become hostile. A tragedy in New York City became the pretext for trampling upon the rights of the Chinese nationally, including in Providence.

In 1909, a young white woman named Elsie Sigel was murdered. The prime suspect was her Chinese lover, William Leon. Leon was believed to have become jealous when Sigel became attached to another Chinese man. When the murder was discovered, Leon was long gone and would never be caught. White hysteria across the nation ensued and the civil rights of Chinese were disregarded. In New York City, the police declared that no Chinese could leave the city. Every Chinese ship leaving New York City’s harbor was searched. And in cities across the nation, lawmen rounded up and arrested countless Chinese men.[14]

Empire Street before the Chinatown is moved out. “A ‘New China’ Here Too,” Providence Journal, February 16, 1913, Section 5, 5.

Providence’s response was a police order directing “all doors and draperies at the entrance to booths or rooms where food is served at Chinese restaurants in the city be removed at once” so that the interiors of Chinese restaurants were visible at all times. In addition it was recommended that every woman teaching Sunday school to Chinese “be of an age and character as to make any such an occurrence as that recently in New York impossible.”[15]

In 1913, another event occurred that exposed how prejudiced some of the whites of Providence could be toward the Chinese. On Chinese New Year in that year, authorities raided Chinatown looking for gambling and opium dens. Six Chinese men were reportedly caught with $12,000 of supposed smuggled opium. The Providence Journal writer of the article lumped all Chinese together, describing them as “careless Chinese, these Empire street denizens!” The writer continued to mock the Chinese by writing that six offenders were brought “to the ‘Melican halls of justice.” (The word “‘Melican” meant “American” as said by a Chinese resident with a heavy Chinese accent.) After the raid a movement arose to remove Chinatown from its location on Empire Street. A subtitle of the article headline read “With Opium Raids Following Hard on New Year’s, Now Wondering Where Their New Chinatown Will Be. – Police May Forbid Another Colony.” The text of the article explained why Superintendent Murray felt it was necessary to scatter the Chinese businesses:

Ordinarily, he said, segregation, the rounding up and hiving in of any class on whom the police wish to keep an eye, is deemed advisable. Not so with the Chinese, he argues, for, as he says, it is easier to keep watch of them and prevent unlawful acts on their part if they are kept apart. Then the very fact that they are coming together in any particular number and with frequency, will result in special police inspection.[16]

Superintendent Murray continued his justification of dispersing the Chinese businesses:

If the Empire street Chinese are well scattered we will know that the appearance in any location of any considerable number of them means that gambling is going on. The Chinese are inveterate gamblers: the vice is inherent in the race. Only by scattering them can we ever hope to minimize the unlawful practice.[17]

These descriptions of the Chinese were very different from earlier statements about the Chinese, such as when the police chief had said that “the Chinese have the same right to keep restaurants, providing they are decent about it and do not disobey the law, as citizens of any other nationality 18] or when the Providence Journal wrote that the Chinese in the city “have done nothing worse than play fan-tan and dominoes on Sunday.” [19] This is evidence that white sentiment and discrimination were unpredictable for the Chinese. As a result, Chinese business owners and workers in Providence’s Chinatown could not prepare against discrimination.

Chinatown was quickly removed from Empire Street. A year later, however, Chinese residents had moved to a new Chinatown in a three-story building on Summer Street.[20]

New Chinatown on Summer Street. “Chinatown on the Move,” Providence Journal, December 13, 1914, Section 5, 7.

Empire Street residents moving to new Chinatown. “Chinatown on the Move,” Providence Journal, December 13, 1914, Section 5, 7.

[Banner image: Empire Street residents moving to new Chinatown. “Chinatown on the Move,” Providence Journal, December 13, 1914, Section 5, 7.]

[Footnotes]

[1] David Norton Stone, Lost Restaurants of Providence (Charleston, SC: American Palate, 2019), 65. [2] “Local Chinese Charter Nationalist Branch,” Providence Journal, February 13, 1921, Section 5, 4. [3] “R.I. Chinese, Asked to Back Warriors, Do It with Money,” Providence Journal, February 18, 1932, 6. [4] “Mott-Street Chinamen Angry: They Deny That They Eat Rats – Chung Kee Threatens A Slander Suit,” New York Times, August 1, 1883. [5] Scott D. Seligman, Tong Wars: The Untold Story of Vice, Money, and Murder in New York’s Chinatown (New York, NY: Viking, 2016), 2. [6] Shih-Shan Henry Tsai, The Chinese Experience in America (Bloomington and Indianapolis, IN: Indiana University Press, 1986), 31. [7] Ibid., 70. [8] Cheng-Tsu Wu, ed., “Chink!” A Documentary History of Anti-Chinese Prejudice in America, Ethnic Prejudice in America Series (New York, NY: World Publishing Company, 1972), 157-164. [9] Iris Chang, The Chinese in America: A Narrative History (New York, NY: Penguin Book, 2004), 176. [10] Wu, ed., “Chink!”, 14. [11] “Anti-Chinese Ordinance,” Providence Journal, October 1, 1899, 12. [12] 1910 Providence Business Directory, 744 (accessed Rhode Island State Archives). [13] “Chinese Element in Providence Slowly Growing,” Providence Journal, February 23, 1908, Section 4, 1. [14] Chang, The Chinese in America, 153. [15] “Order to Chinese Restaurants,” Providence Journal, June 25, 1909, 1. [16] “A ‘New China’ Here Too,” Providence Journal, February 16, 1913, Section 5, 5. [17] Ibid., Section 5, 10. [18] “Anti-Chinese Ordinance,” Providence Journal, October 1, 1899, 12. [19] “Chinese Element in Providence Slowly Growing,” Providence Journal, February 23, 1908, Section 4, 1. [20] “Chinatown on the Move,” Providence Journal, December 13, 1914, Section 5, 7.