Most public bus routes that crisscross Rhode Island today overlay track beds that once supported-electric trolleys and horsecars. Before the railways, the rickety omnibus and its rough and tumble predecessor, the stagecoach, plied these same highways on primitive turnpikes. Post roads, maintained by the state, guided the country’s early postal delivery system. The transportation lineage spirals even further back in time to isolated white settlers venturing into Rhode Island hinterlands over frontier bridal paths. But the transportation matrix does not stop here either. Before the arrival of white European settlers, Native Americans had developed a system of paths through the forests of the Narragansett Bay-region.

A Pequot trail snaked out of the South Main Street area of Providence to outlying districts as-far away as the neighboring states of Connecticut and Massachusetts. Roger Williams, Rhode Island’s founder, was so impressed by the-engineering of the Narragansetts in South County that he described their seventeenth century transportation web “as hard and firm as any roads in England.” To a degree these primitive pathways, some six to ten feet-wide, parallel the modern interstate highway systems of Routes 95 and 195 that connect Rhode Island to the rest of the world today. Some of the instate routes, with only minor variations, can trace a pedigree from these silent Indian trails to the congested routes of lumbering Rhode Island Public Transit Authority buses four centuries later.

Map of Providence in 1664 showing home lots of original proprietors and Indian trails, the only roads at that time (From The Providence Plantations for Two Hundred and Fifty Years).

During, the first two hundred years of Rhode’ Island’s development many of its residents looked to the sea as a way to travel and make a living. Canoes, sloops, ships and other wooden vessels slipped out from a hundred points along the indented coast of the “Ocean State” carrying travelers and goods to places far and near. At the beginning of the nineteenth century the state began an economic transformation that no longer required a maritime compass.

Colonial entrepreneurs slowly abandoned chancy international sea trade. The manufacturing experiments of Samuel Slater and Moses Brown created an opening for the English Industrial Revolution in America. The success of Slater’s Mill in Pawtucket created a modest industrial orbit in the Blackstone Valley. Many investors now turned the navigator’s eyepiece, not seaward, but inland along the many streams that flowed into the Narragansett Basin. Freshwater and waterfalls, not saltwater and sea winds, would churn Rhode Island’s next economic gale.

As early as the seventeenth century a string of ferries provided direct crossings over salt water barriers. As technology developed and the wealth of the colony increased, bridges slowly replaced the shorter ferry routes. The new industrial workshops, however, required a land based system of transportation to service the factories that dotted the inland waterways. A web of turnpikes and roads threaded their way across the state’s industrial valleys connecting mills to markets arid supplies. For isolated village factories a turnpike to the port of Providence was a lifeline. The growth of mills actually increased traffic on Narragansett Bay. Turnpike corporations, often subscribed to by local cotton merchants, petitioned for state charters to build private toll roads.

Turnpike milestone indicating the traveler was two miles from Providence ((Courtesy of Providence Public Library Digital Archive)

Turnpikes began in Rhode Island in the 1790s, and initially pushed toward border markets in Massachusetts and Connecticut. After the turn of the nineteenth century over a dozen such roads connected Providence with its hinterlands especially in the northern and western parts of the state where many of the textile mills were located. Zachariah Allen, the visionary textile manufacturer, built his mills in North Providence and Smithfield close to existing turnpikes. Samuel Slater invested $40,000 in turnpike stock partially to enhance his own textile interests.

Turnpike owners imposed various fees for the passage of animals, vehicles or freight. The Providence and Boston Turnpike, chartered in 1800, was the busiest in the state. A horseman paid six cents; a wagon was charged twelve cents; and a single pig cost a penny with a one-third discount for a herd of ten or more. Local residents influenced passage of state legislation to exempt them from paying a fee when traveling to religious services, a mill or a town meeting.

The golden age of the turnpike in Rhode Island, as elsewhere, spanned the decade before and after the War of 1812. The state or local towns eventually took over most roads, especially during the generation between 1853 and 1873. In 1864 the Rhode Island General Assembly authorized turnpike and toll bridge corporations to sell their property to the government. The nine remaining franchises soon passed out of the realm of private enterprise.

One corporation that dragged on for almost a century was the Glocester-West Glocester turnpike. At its decrepit demise in 1888, it was allegedly the last remaining road with toll gates in the nation. Stockholders were glad to get what they could for the profitless roads especially after the introduction of the railroad. Historian George Rogers Taylor in his influential work, The Transportation Revolution, maintained that the toll roads were mostly obsolete even before trains made an appearance. The Providence-Pawtucket route was a profitable exception serving as a link between the two cities and as a gateway to Boston. Taken over by the state in 1833, the road brought in over $4,000 a year. It became a “free” way in 1869.

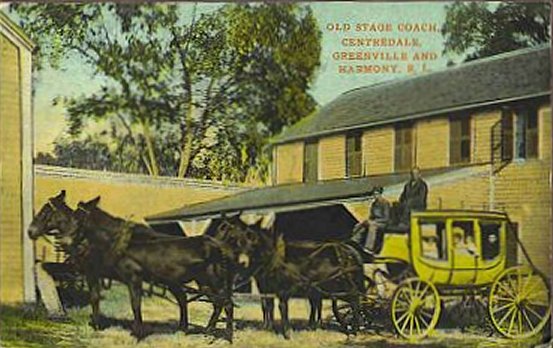

The building and extension of turnpikes in Rhode Island spurred the development of the stagecoach, the “symbol of rapid transportation in 1815.” A stage from Providence to Boston ran sporadically as early as the 1740s. Drivers, according to legend, would not embark for a destination until assured of a full load. A tongue-in-cheek folklore claimed that operators gave sufficient notice before leaving so that “passengers could settle all their worldly affairs and make their wills before commencing such an arduous and dangerous journey.” Regular service between the two colonial cities began in earnest in 1767 with daily trips commencing in 1793 at a cost of one dollar each way. Ironically, the development of swift steamers from New York to Providence enhanced the patronage of stagecoaches as New York travelers would disembark at Providence for the trip to Boston, a journey which was longer by sea due to the geography of the region.

Horse and stagecoach with “Broadway Stage Co., M. E. Fitzgerald, Manager” inscribed on the stagecoach (Courtesy of Providence Public Library Digital Archive)

These massive coaches, loaded with freight and up to a dozen passengers, sometimes arrived simultaneously in Providence and drivers raced to arrive first “seesawing along the leathern thorough braces.” Horses were changed several times along the way to quicken the trip which reached average speeds of 6 to 8 miles per hour and sometimes as high as 11. In its heyday in 1829, stagecoach service between New England’s two leading towns totaled-328. Trips a week and carried an estimated 24,000 passengers annually. “Market Square and-Benefit Street and North Main Street,” a Providence Journal article reported, “rang merrily with the hoof beats and the rumble of the coach and four echoed the blare of the long brass coach horn.” In 1832 a traveler on this route exclaimed that “we were rattled from Providence to Boston last Monday in four hours and fifty minutes including all stops on the road. If anyone wants to go faster, he may send to Kentucky and charter a streak of lightning, or wait for a railroad, as he pleases.”

Directly related to the establishment of turnpikes and stagecoaches was the growth of hostelries, taverns and guest houses along the stage routes. “The stagecoach,” according to a Journal article, “carried animation along with it from village to village; and, when the driver’s horn announced its approach, all the superannuated uncles, idle small boys, and stock loafers would begin to put themselves in motion towards the tavern, that they might enjoy the temporary excitement when the coach arrived.” In Providence between 1845 and 1850, most of the stagecoach lines operated out of the Exchange Hotel and the Weybosset House where passengers enjoyed a separate waiting room before embarking for Greenville, Scituate, Chepachet, Manton, Warwick, East Greenwich, Coventry or other Rhode Island destinations. Patrons registered at a convenient booking office in designated establishments.

In the 19th century, almost all of the alignment of modern US 44 in Rhode Island was part of an early turnpike route. From the Connecticut line in Putnam to the Smithfield town line, what is now the Putnam Pike (shown here) was part of the West Glocester Turnpike (Connecticut line to Chepachet) and the Glocester Turnpike (Chepachet to Smithfield line). The continuation of the road in Smithfield and North Providence was another turnpike road known as the Powder Hill Turnpike, running along the alignment of modern Smith Street. Between East Providence and Taunton, the road was part of yet another turnpike, the Taunton and Providence Turnpike, running along modern Taunton Avenue and Winthrop Street. (Courtesy of Providence Public Library Digital Archive)

The stagecoach had little inland competition until the development of the railroad, “one of the most revolutionary inventions of all time,” according to transit historian George Rogers Taylor. However, completion of the Blackstone Canal in 1828 between Providence and Worcester provided a unique rival to the coach route between the two cities. In June 1835, the first steam railroad swayed between Providence and Boston, establishing a profitable line for freight and passengers. Two years later service began between Providence and Stonington, Connecticut, with ferry connections to New York City. In 1847 rail traffic also began to Worcester and quickly eclipsed both stagecoach and canal operations.

The iron horse clearly condemned the stagecoach to oblivion. Ironically, the Boston based Eastern Stage Company tried to organize a monopoly of stage service in Rhode Island and throughout New England in 1818, just before the coming of the train. Other business interests made similar efforts later in the century to monopolize omnibus, horsecar and trolley service in the state. Contemporaries along the road of the Boston to Providence stagecoach in 1835 worried that the railroad would end economic enterprise along the old turnpike altogether. According to a newspaper account, “They could not conceive it possible for such a mighty enterprise as the turnpike to be abandoned without accomplishing the ruin of all who derived subsistence therefrom, and in this opinion they were supported by the prevailing sentiment of the country at that time, which regarded railroads as a curse rather than a blessing.” The speed, comfort and relative low fares of the railroad were beyond the competitive reach of the stagecoach. Where there were no other means of transportation the coach continued to flourish. Several lines survived into the twentieth century.

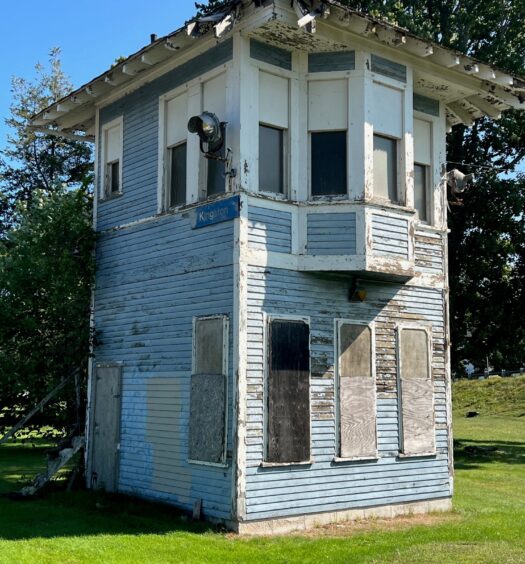

Stagecoach on Route 44 in Glocester around the start of the 20th century (Sanford Neuschatz Collection)

The stagecoach from Providence to Putnam, Connecticut lingered awhile after the introduction of the railroad. In 1876 the citizens of Georgiaville rebelled against the high prices of the railroad and patronized the slow but reliable stage: “People are contented to ride slow and cheap,” a newspaper article remarked, “rather than quick and dear.” By the waning days of the nineteenth century the few remaining stagecoaches were nevertheless simply vestiges of an earlier era. Some enterprising owners like the proprietor of the East Providence stage route sold franchises “at a high price” to the Union (Horse) Railroad. By 1892, the three remaining stagecoach lines out of Slatersville to Pascoag, Woonsocket and Millville, Massachusetts were retired by the introduction of rural branches of larger railroads.

That the stage lasted as long as it did was in some ways a testament to the handlers. John Richards, who began his career as a driver on the Providence-Danielson stagecoach during the administration of Andrew Jackson, was still driving his “box” in the 1890s “in determined spite of and with a kind of contempt for, those modern conveyances, the steam car and steamboat.” Richards, like many other drivers, was an owner-operator who hung on after other prudent businessmen would have abandoned the business. At the turn of the twentieth century the last remaining stagecoach line traversed the backwoods from Olneyville to Scituate, Foster and Danielson, Connecticut. The Providence and Danielson (Electric) Railway opened in June 1901, causing the demise of the last stagecoach line. An article on the new system became an obituary for the old stage, “The world will need its services no longer.”

[Banner image: Horse and stagecoach with “Broadway Stage Co., M. E. Fitzgerald, Manager” inscribed on the stagecoach (Courtesy of Providence Public Library Digital Archive)]