The letter penned by Sullivan Ballou, a major in the 2nd Rhode Island Infantry Regiment hailing from Smithfield, one week before he fought at the first Battle of Bull Run, is probably the most famous wartime love letter in American history. I still remember hearing it read for the first time in the initial episode of Ken Burns’s mini-series documentary, The Civil War. Tears welled up in my eyes as I listened to Paul Roebling read the letter. I was hardly alone, as attested by the outpouring of emotion from other viewers after the PBS show aired.

“If I do not [return], my dear Sarah,” Ballou’s letter reads in part, “never forget how much I love you, nor that, when my last breath escapes me on the battlefield, it will whisper your name. . . . [I]f the soft breeze fans your cheek, it shall be my breath; or the cool air cools your throbbing temples, it shall be my spirit passing by. Sarah, do not mourn me dear . . . and wait for me, for we shall meet again.”

Less well known is another touching wartime love letter associated with Rhode Island, this one written by President George H.W. Bush to his future wife, Barbara. At the time, in December 1943, Ensign Bush was undergoing his final training as an aircraft carrier pilot at the Naval Auxiliary Air Field at Charlestown, Rhode Island. In addition to the intense love each of Ballou’s and Bush’s letters vividly reveal for the respective special women in their lives, there is a common emotion in both letters that exceeds even those deep feelings: love of country and duty to country.

While the passages in Ballou’s letter about his wife Sarah understandably gain the most attention, less appreciated is the Smithfield resident’s passionate attachment to the Union cause. Ballou writes, “If it is necessary that I should fall on the battlefield for my country, I am ready. . . . I know . . . how great a debt we owe to those who went before us through the blood and suffering of the [American] Revolution, and I am . . . perfectly willing to lay down all my joys in this life to help maintain this government, and to pay that debt.”

George Bush wrote his best love letter to his fiancée Barbara on December 12, 1943, the day their engagement was announced in the New York Tribune. He probably wrote this letter sitting at a small desk in his cramped room at the Bachelor Officer Quarters at the Charlestown base. While the prose of this letter does not rise to the level of Ballou’s, it still gives me a lump in my throat, particularly on this day that I write this piece, the day after Bush’s death.

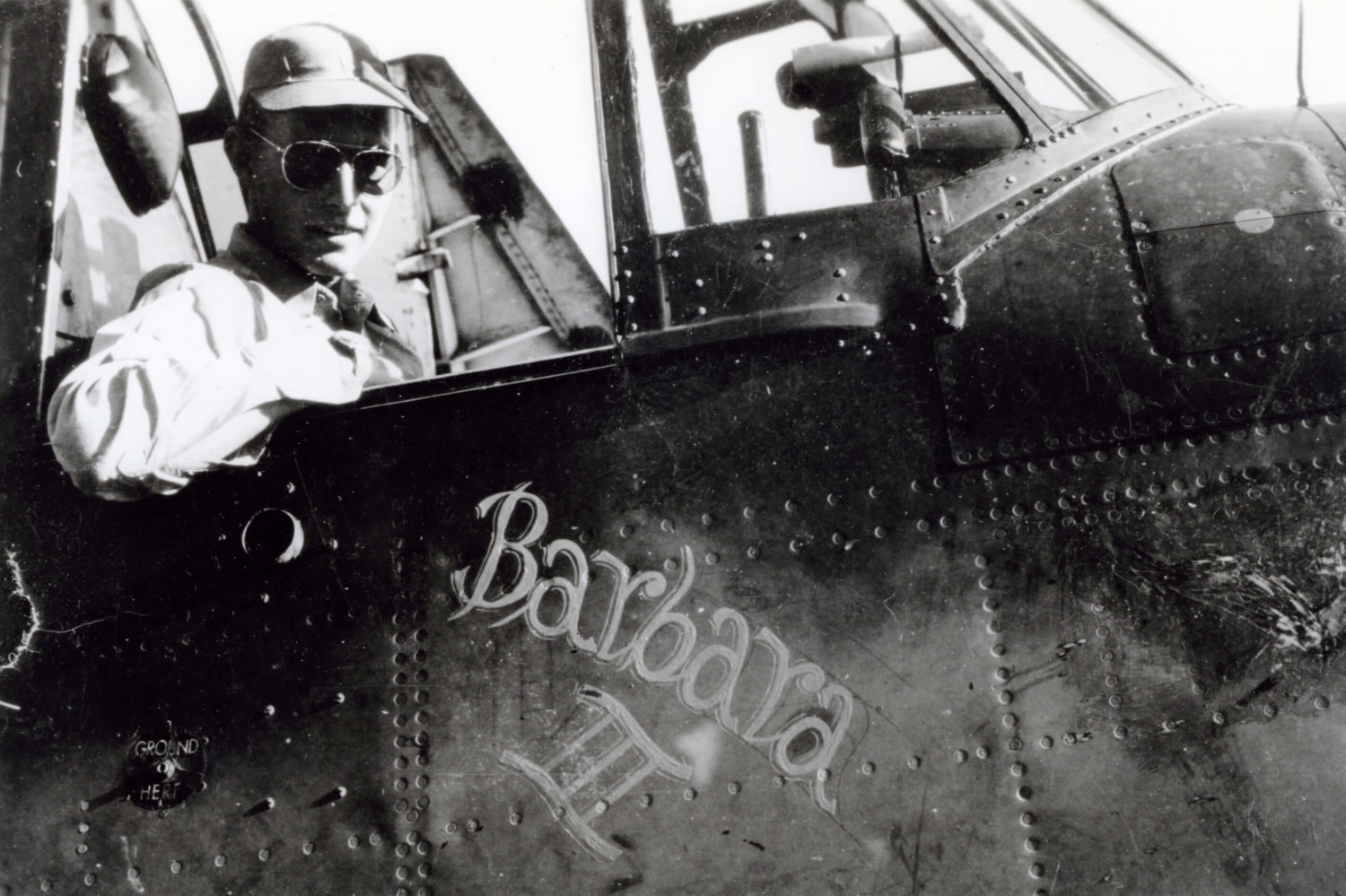

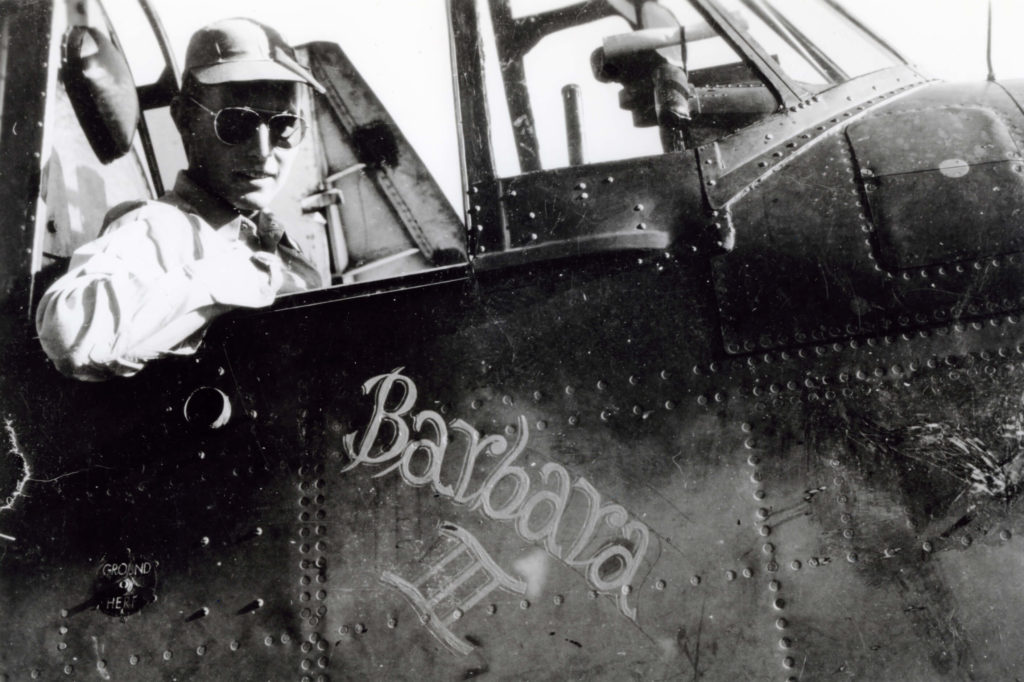

Pilot George H.W. Bush named all of the airplanes assigned to him for his fiancée Barbara. He named the TBF Avenger assigned to him at Charlestown as Barbara II, so this photograph must be from 1944 after he departed Charlestown in mid-January of that year (George H.W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum).

Bush wrote to Barbara, “it should be simple for me to tell you how desperately happy I was to open the papers and see the announcement of our engagement, but somehow I can’t possibly say all in a letter. I should like to.” He continued: “I love you, precious, with all my heart and to know that you love me means my life. How often I have thought about this immeasurable joy that will be ours someday. How lucky our children will be to have a mother like you.”

Bush then addressed the tension he felt between his powerful yearning to be with his fiancée (whom he nicknamed Bar) and the strong duty he felt to serve overseas at this crucial time in the country’s history:

As the days go by th[e] time of our departure [to the war zone] draws nearer. For a long time I had anxiously looked forward to the day when we would go aboard and set to sea. It seemed that obtaining that goal would be all I could desire for some time, but, Bar, you have changed all that. I cannot say that I do not want to go—for that would be a lie. We have been working for a long time with a single purpose in mind, to be so equipped that we could meet and defeat our enemy. I do want to go because it is my part . . . .

Still, Bush knew Barbara had changed his life’s goals. He continued:

Even now, with a good while between us and the sea, I am thinking of getting back. This may sound melodramatic, but if it does it is only my inadequacy to say what I mean. Bar, you have made my life full of everything I could even dream of—my complete happiness should be [my] token of my love for you.

Ballou was killed in battle shortly after penning his letter at the first Battle of Bull Run, giving even more poignancy to his last love letter. Bush survived the war—barely. On September 2, 1944, after completing a mission bombing a Japanese installation on a small island in the Pacific and having his airplane riddled with enemy bullets, Bush had to bail out and parachute into the sea. His two crewman, including Radioman Second Class John Delaney of Providence, died; their bodies were never recovered. Bush waited four agonizing hours on a small raft, while several Navy fighters overhead warded off approaching Japanese small boats eager to capture the fallen pilot. Eventually, Bush was rescued by a lifeguard submarine. Throughout 1944, Bush flew 58 combat missions for which he received the Distinguished Flying Cross and three Air Medals.

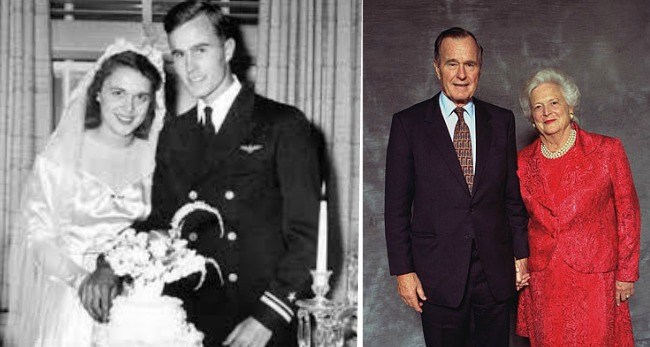

George and Barbara shown on their wedding day on January 6, 1945, and some 70 years later (George H.W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum).

George and Barbara were finally married on January 6, 1945. They were thus able to continue one of the great love stories of our time—they were married for 73 years, becoming the longest married couple in U.S. presidential history. They also continued to serve our country for decades.

The Ballou letter is held by the Rhode Island Historical Society. There is some controversy over who wrote the letter—Major Ballou or a friend of his in his regiment. Copies of the Bush’s letter to Barbara are held by the George H.W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum at College Station, Texas. Barbara’s letters to George during this period have disappeared—Barbara, who passed away in April of this year, may have had a hand in that. Fortunately, George’s December 12 letter has survived. Parts of the December 12 letter—including those quoted in this article—were recently were read out loud by George, with Barbara at his side, and filmed by their family.

[Banner Imager: Pilot George H.W. Bush named all of the airplanes assigned to him for his fiancée Barbara. He named the TBF Avenger assigned to him at Charlestown as Barbara II, so this photograph must be from 1944 after he departed Charlestown in mid-January of that year (George H.W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum).]