As a collateral descendant of Daniel Hitchcock (first cousin, nine times removed), I have always been fascinated by the short but important life of this colonel from Providence, Rhode Island, who was taken by illness following the Battle of Princeton at the young age of thirty-seven. Likely because there is neither an existing house nor a portrait of him, Hitchcock is largely forgotten despite the fact that he had served as a colonel in the Continental Army in five battles in the Revolutionary War by January 1776.

Hitchcock was born in Springfield, Massachusetts on February 15, 1739, son of Capt. Ebenezer and Mary (Sheldon) Hitchcock. He was the youngest of fourteen children. Daniel attended Yale, but unfortunately his mother Mary died in January 1760 when Daniel was twenty, and she did not live to see him graduate a year later in 1761.[1]

He then moved to Northampton, Massachusetts, where he studied law. He relocated once again, this time to Providence, where he opened his law practice.[2]

A Providence resident named Benjamin Cowell noted that Daniel, “settled in Providence, opened an office, and began his professional career with good prospects, and under favorable circumstances. He was a fine scholar, of refined taste and elegant manners, in fact a finished gentleman of the old school.”[3]

In the summer of 1772 the Sons of Liberty in Rhode Island boarded His Majesty’s Schooner Gaspee, set fire to the schooner that had been harassing patriot smuggling operations, and burned it to the water line. This was the most significant act of rebellion against British governmental policy in between the Boston Massacre in 1770 and the Boston Tea Party in 1773. It was largely overlooked until Steven Park, then professor of history at the University of Connecticut, published his doctoral dissertation as a book. It was Steven Park, along with the Gaspee Days Committee, that discovered that Daniel Hitchcock was likely to have been among those Sons of Liberty in Providence who organized the plan to seize the British ship.[4]

The evidence implicating Hitchcock as a both planner and as one of those who boarded the schooner is compelling. When a commission in 1773 investigated the events that led to the burning of the ship, Hitchcock was summoned, as were two other lawyers, to appear and testify. Each of the three wrote signed depositions claiming they were too busy with their caseloads to appear. In January 1773, Hitchcock wrote to the commissioners,

“May it please your Honors:—Late last night I had a citation from Providence to appear before you this day at 11 o’clock in the forenoon, to give evidence with regard to the burning of the schooner Gaspee; and as I detest all such open violations of the law, should have been willing to have waited upon your honors to let you know every thing within the compass of my knowledge relative to that matter, had not my engagements at Kent Court, in this place, absolutely forbid my attendance; and therefore hope your honors will pardon me on that account; but every thing I know touching that matter I am ready to relate.”[5]

Hitchcock and the other lawyers conspired to put the same narrative in writing, with the false story that, while the three of them did indeed each have dinner at the Sabin Tavern in Providence while the attack on the Gaspee was being planned, they somehow were not aware of the gathering the tavern that night of people who paraded with a drummer to their embarkation point at the harbor and proceeded to row to, and then burn, the Gaspee.

A year later the Rhode Island General Assembly appointed Hitchcock as part of a commission to revise the colony’s military laws. Three days after the Battles of Lexington and Concord, Hitchcock was elected lieutenant colonel of the Providence Train of Artillery. Just a month later he was made colonel of the Second (or Providence) regiment in the Rhode Island Army of Observation. From 1775 through April 1776, Hitchcock’s regiment was among the many that besieged British-held Boston.[6] During that time fellow Rhode Islander General Nathanael Greene wrote of his regimental commanders, “Colonel Varnum and Colonel Hitchcock are good disciplinarians.”[7] Hitchcock served as field officer of the day in early March for the left wing of the American force besieging the city.

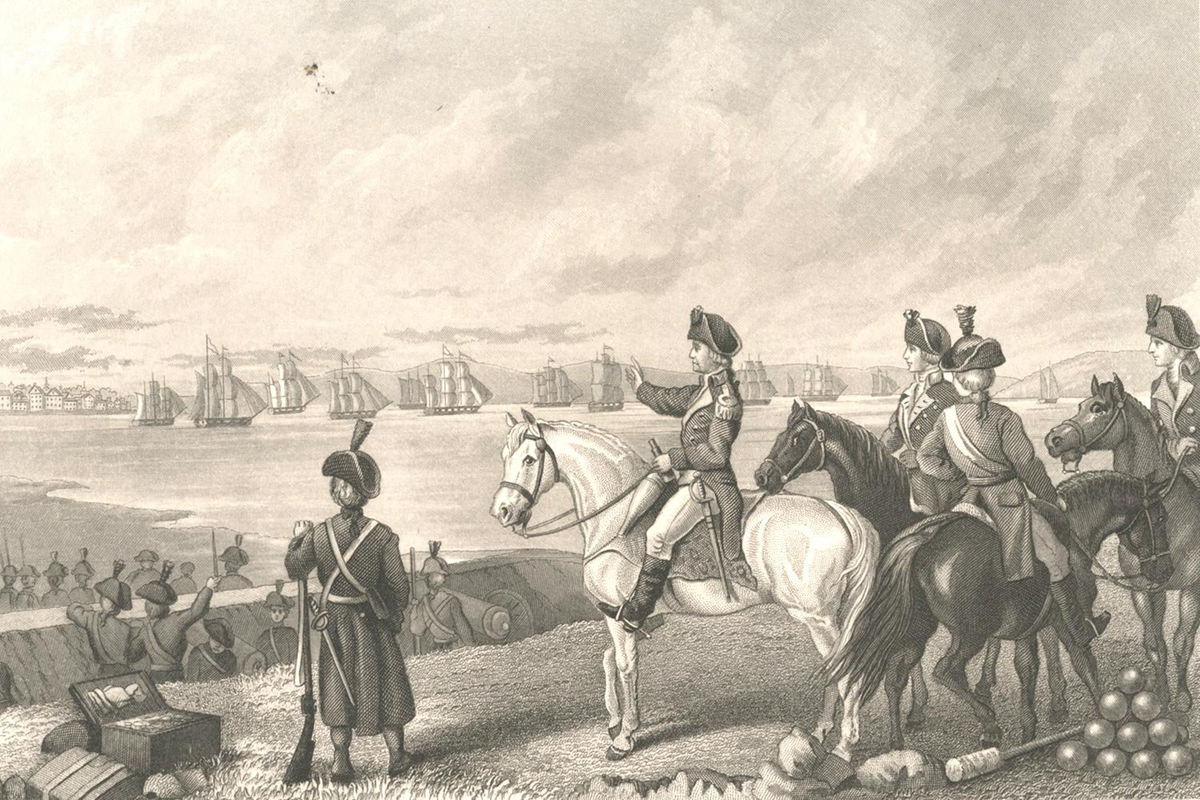

George Washington and other officers of the Continental Army who had set siege to British-occupied Boston view with satisfaction the departure of the British forces on Royal Navy ships. Colonel Hitchcock of Rhode Island was among the key regimental leaders in the Continental Army.

The only other letters written by Hitchcock known to exist are three from the summer of 1776 to John Adams while Hitchcock served during the infamous New York Campaign that resulted in patriot forces fleeing from Long Island to Manhattan in the face of a superior, more professional opponent. Hitchcock was the commander of the 11th Continental Infantry Regiment, a regiment of Rhode Islanders. Prominent Rhode Island officers in the regiment included Israel Putnam and Jeremiah Olney, each of whom in future years would commend the 2nd Rhode Island Continental Regiment.

Hitchcock’s letters to Adams demonstrate that he felt comfortable expressing his opinions in writing, even if they were critical of other significant patriot leaders such as Benedict Arnold. For example, in his first letter to Adams, Hitchcock wrote,

“Another thing that I fear will have a Tendency to brake the Band of Union (for give me Leave to say, I am under better Circumstances to know it, than any General) is the Advancing Officers faster to Posts of Honor to the Southward, than Northward; every one that was Colonels there last Year, are Now, made Brigadiers, But there is not an Instance of that kind to the Northward, excepting Arnold, who in my Opinion and in the Opinion of every Colonel in the Army, would have been amply rewarded for his Enterprise, by being made a Colonel of a Regiment; and if he had been made that instead of what he was, I believe Quebec this Day would have been ours.”[8]

Hitchcock apparently was an acquaintance of Adams, for Hitchcock’s letter is both professional and personal, as well as long. It includes his dissatisfaction that his peer, James Mitchell Varnum, was to be promoted over him for brigadier general. He wrote, I “am satisfied with Regard to the Advancement of Officers to the Southward, tis certainly right, that southern Brigades should have southern Generals; the hardest Pill is when one Colonel is put over another’s Head, of the same State, for Instance suppose Colo. Varnum should be promoted over Me, which I know he is constantly dogging the General to do; I should instantly resign, because I know my Character would inevitably suffer in the State from whence we came.” He added, “you deserved my sentiments; I’ve freely given them.”[9]

In early August Adams replied, explaining to the colonel the various challenges for the fledgling United States Congress to appoint leaders as colonels versus brigadier or major generals. For example, Adams wrote, “We must not deviate from the line of succession. If we do, we are threatened with disgusts and resignations. How do we follow the line? Wooster, Heath and Spencer ought to be made Major Generals (in my opinion). But is this the opinion of the Army?”[10]

Unknown to Hitchcock, Adams had already successfully proposed to Congress that Varnum be promoted to brigadier general. Congress could not add a second colonel from Rhode Island to the list of brigadiers since other states—both northern and southern—also needed fair representation. These political pressures surely impacted the morale and commitment of many an officer, including, infamously, Benedict Arnold.

In his third and final letter to Adams, Hitchcock wrote further upon this topic and asked Adams to keep the letter confidential so that his criticism of Varnum would not be shared with other members of Congress and then be leaked back to Varnum. He also offered a strong critique of the poor performance of soldiers in the militia, since they had often deserted the battlefield after an initial round of fire, much to the shock and frustration of Hitchcock, as well as to General George Washington. Hitchcock opined sternly,

“The Militia are not worth a farthing, in this Time of Extremity, the Militia are passing Home by Hundreds in a Drove, affrighted and scared out of their Wits; I am positive they have done this Army infinite Damage; for they tell Us all is gone and the Regulars must overcome Us; our Men are disheartened by such Language, to such a Degree, that it seems to Me Nothing but the immediate divine Impulses will again inspire them with Courage; for Heaven’s Sake, for our Country’s Sake and for Liberty’s Sake, do let Us have an established Army.”[11]

Hitchcock’s regiment built Fort Putnam, which stood on the high ground on the present site of Washington Park in Brooklyn, and General Greene ordered that the fort be garrisoned by Hitchcock’s regiment.[12] Hitchcock’s 11th Continentals were in the center of the American defensive line during the Battle of Brooklyn Heights on August 27.[13] It was a searing hot day, and Hitchcock’s soldiers must have suffered greatly, but details or documents related to his regiment’s actions that day are lacking. Hitchcock himself was not present at the battle; he was absent and likely in bed sick with his first bout of tuberculosis.[14] It is possible that he suffered with another disease such as yellow fever that had sidelined other regimental colonels such as Jedediah Huntington of Connecticut.

After that New York campaign, Adams followed up with Hitchcock in early October, expressing his opinion that the Continental Army lacked proper military training. This was also expressed by Adams in his personal diary on October 1, when he recorded that he asked Congress to consider creating an academy for the army. Congress unfortunately did not listen to the wise idea of Adams. In his letter to Hitchcock, Adams opined,

“Your Army, Sir, give me leave to say, has been ill managed in two most essential points. The first is, in neglecting to train your Regiments and Brigades to the manual Exercises and the Manoeuvres . . . But instead of these martial, manly and elegant Exercises, they have been kept constantly at Work in digging Trenches in the Earth; which keeps them constantly dirty.”[15]

Hitchcock’s regiment followed General Washington and the rest of the haggard army that had escaped New York as they plodded through the mud across New Jersey and eventually into Pennsylvania. Hitchcock was part of the third division along with Colonel John Cadwalader and Brigadier General James Ewing that moved down the Delaware and were encamped at Bristol, Pennsylvania. According to historian Richard Ketchum, “Hitchcock’s brigade at Bristol had almost no camp equipment, blankets, or stores of any kind.”[16]

Washington ordered the brigades of Cadwalader, Ewing and Hitchcock to cross the Delaware River on December 25 and help attack Trenton from south of the city, while Washington and Greene attacked with two prongs from the north. Because the frozen Delaware River in that stretch was mostly thin ice, the river was too dangerous to cross with artillery and the three brigades were unable to attack as Washington had hoped.[17] Washington was still able to achieve complete surprise and score a major moral victory when he roused and then captured the unsuspecting Hessian garrison of Trenton.

Hitchcock and his Rhode Islanders proved their immense worth at both the unheralded second Battle of Trenton, also called the Battle of Assunpink Creek, as well as at the famous Battle of Princeton the very next day. Hitchcock was already suffering a severe illness that was likely tuberculosis, and yet he provided excellent leadership in the heat of battle at Assunpink Creek.

When the British attacked with 5,000 men on January 2, Colonel Edward Hand’s Pennsylvania riflemen repulsed them three times. The only known references to Hitchcock’s regiment at this battle are the writings of private. John Howland, who recalled being next to “the noble horse of Gen. Washington . . . I was pressed against the shoulder of the general’s horse . . . When I was about half way across the bridge, the general addressed himself to Col. Hitchcock, the commander of the brigade, directing him to march his men to that field, and form them immediately.” Later, Daniel Smith, a sergeant in another New England regiment, recalled that at sunset the army, safely positioned atop a hill overlooking the Assunpink, was “ordered to take refreshments, and during the night the fires were ordered to be rebuilt.”[18]

During the night Washington’s army was on the move again, marching several miles north to the college town of Princeton. Hitchcock missed the Battle of Princeton because of his sufferings with tuberculosis that would take his life days later. Sergeant Daniel Smith provided his recollection of the early part of the battle that included Hitchcock’s Rhode Islanders. He recalled of General Hugh Mercer’s force that was composed of mostly Pennsylvania militia, “His men deserted him and he was left almost alone and fought until he was bayoneted to death. . . . The American Army was immediately formed and Greene’s [actually Hitchcock’s] Brigade came next to the remnant of this Pennsylvania detachment. The battle for a short time was very warm.”[19]

“The Death of General Mercer at the Battle of Princeton, January 3, 1777,” by John Trumbull, ca. 1789. While Mercer was celebrated in a glorious death sacrificing for his country, Colonel Hitchcock, who died shortly after the battle from prolonged illness, has not been so celebrated (Yale University Art Gallery)

Lieutenant Stephen Olney of Hitchcock’s Regiment recalled of the battle, “When they came up with the British regiment, Colonel Hitchcock was sick and absent. Major Israel Angell, the only field officer present, made a short speech to the regiment, encouraging them to act the part that became brave soldiers, worthy of the cause for which we were contending . . . field pieces, loaded with grape shot . . . made the most horrible music about our ears I had ever heard.”[20]

Hitchcock and his brigade of New Englanders had much to be proud of, and the Founding Fathers took notice as Hitchcock faced death from enemy fire as well as disease. Dr. Benjamin Rush wrote with praise on January 6 from Bordentown, New Jersey, “Much credit is due to a brigade of New England men commanded Colonel Hitchcock in both actions; they sustained a heavy fire from musketry and artillery for a long time without moving; they are entitled to a great share of the honor acquired by our arms at Princeton.”[21]

Hitchcock was dying, likely lying in his or another officer’s horse-drawn wagon. Washington and the rest of the army marched northeast to encamp for the rest of the winter at Jockey Hollow, outside of Morristown, New Jersey. Perhaps Hitchcock spent his last days in an army hospital or private home near what is today’s Morristown green, for that is where the colonel was buried after he died on January 13, 1777.

Several soldiers and officers recorded Hitchcock’s funeral on the 14th. Thanks to those diaries, the location of Daniel’s grave is known to be in the cemetery of the Presbyterian Church next to Morristown Green. Sergeant William Young of the 3rd Battalion, Philadelphia Associators wrote in his diary, “Colonel Hedgcok was buried in the Military Taste in the Rev. Mr. Jones Burying Ground,” referring to the minister of the Presbyterian Church, Rev. Timothy Jones.

Capt. Thomas Rodney, who commanded a company of Delaware Light Infantry soldiers, presided over the military funeral.[22] He recorded a long and detailed description of the funeral procession. He included the phrase “rested on their arms reversed,” referring to a specialized position for holding muskets called “mourn arms:”

“This day the [Light] Infantry was ordered to Bury Col. Hitchcock with the Honours of war and as he was a Continental officer I took the command myself. Order of the funeral. 40 of the Infantry in 4 lines, 10 in arms reversed in each line, youngest Lieutin front, Eldest in Center, Capt. in the Rear—followed by the Fifes and Drums—next the Bier followed by the mourners—then the officers and then the Battalion in lines of Ten as patoons [platoons] in open order as the infantry. This was the order of march, but the Battalion first stood in the order described and wheeled to the wright [right] and left backwards and formed a line for the Infantry, Bier, mourners, officers, and etc. to pass through then closed up and followed as described. When we got near the grave the youngest Lieut. gave the word for the Infantry to wheel to the Right and Left backwards to form a lane for the corpse and mourners to pass through and to rest on their arms—buried his Corpse, mourners and officers past through and I followed them and took post then in the front and as soon as I got there ordered the Infantry to shoulder and wheel to the Right and left inwards and march up in Quick Time and close order to the grave—then gave the word to wheel to wheel to the left and form Battalion, then make ready and fire repeated three Vollies—when the Infantry formed a lane the Battalion did the same and Rested on their arms reversed and shouldered and closed up at the same time also and followed to the grave but did not fire.”[23]

“George Washington at the Battle of Princeton,” by Charles Wilson Peale in 1781. Hitchcock was too ill to participate in the battle and died of his illness shortly afterwards. Washington survived the battle and is surrounded by captured enemy battle flags (Yale University Art Gallery)

For centuries, Colonel Daniel Hitchcock’s grave remained unmarked. Thankfully, although its exact location in the cemetery is unknown, Rhode Island historian Daniel Popek led efforts with the help of a National Park Service ranger to have a new headstone from the Department of Defense created and erected at the cemetery. A special ceremony was held to unveil the new headstone on July 12, 2008.

[This article originally appeared in the Journal of the American Revolution at www.allthingsliberty.com]Notes:

[1] Massachusetts, Town and Vital Records, 1620-1988www.ancestry.com/search/collections/2495/; Henry Johnston, Yale and Her Honor Roll in the American Revolution, 1775-1783 (New York: Privately Printed, 1888), 226-227. [2] Providence Gazette, December 8, 1770. Daniel Hitchcock announced the opening his law office in the house of Dr. Amos Throop. “Extracts from the Journal of William Jennison, Jr., Lieutenant of Marines in the Continental Navy.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 15, No. 1 (1891), 101-10. [3] Daniel Popek, They Fought Bravely but Were Unfortunate: The True Story of Rhode Island’s “Black Regiment” and the Failure of Segregation in Rhode Island’s Continental Line, 1777-1783 (Bloomington, IN: Author House, 2015), 40. [4] The burning of the Gaspee took place on June 9 off the shore of Warwick, Rhode Island, just south of Providence. [5] Daniel Hitchcock, January 20, 1773, in William R. Staples, The Documentary History of the Destruction of the Gaspee (Providence, RI: Rhode Island Publications Society, 1990), 72. [6] Phelps, Yale and Her Honor Roll, 227. [7] Nathanael Greene to Samuel Ward, October 16, 1775, Papers of Nathanael Greene (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1976), 1:134. [8] Daniel Hitchcock to John Adams, July 22, 1776, Adams Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society. [9] Hitchcock to Adams, August 22, 1776, Adams Papers. [10] Adams to Hitchcock, August 3, 1776, Adams Papers. Adams referred to David Wooster and Joseph Spencer of Connecticut, who had both led provincial regiments in the French and Indian War, as well as William Heath of Massachusetts. [11] Hitchcock to Adams, July 22, 1776, Adams Papers. [12] Greene, General Orders, June 17, 1776, Greene Papers. [13] David Smith, New York 1776: The Continentals’ First Battle (New York: Osprey Publishing, 2008), 48-49. [14] Popek, They Fought Bravely, 77. [15] Adams to Hitchcock, October 3, 1776, Adams Papers. [16] Richard Ketchum, The Winter Soldiers: The Battle for Trenton and Princeton (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1973), 243. [17] George Washington to John Cadwalader, December 24, 1776, George Washington Papers, Founders Online, at founders.archives.gov. [18] Edward Martin Stone, The Life and Recollections of John Howland, Late President of the Rhode Island Historical Society (Providence: George H Whitney, Printer, 1857), 2-73; Sergeant Daniel Smith Pension File, Revolutionary War Pensions, National Archives, accessed at Fold3.com. [19] Edited, corrected version of Smith’s pension application found in Popek, They Fought Bravely, 93. [20] Popek, They Fought Bravely, 94. [21 ]Benjamin Rush to Richard Henry Lee, January 6, 1777, quoted in Phelps, Yale and Her Honor Roll, 61. [22] “Journal of Sergeant William Young,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 8, No. 3 (October 1884), 268. [23] “Diary of Captain Thomas Rodney, December 1, 1776-January 28, 1777,” Library of Congress Manuscripts, MMC-3249, Mss. 21,992, Rodney Family Papers, Microfilm.