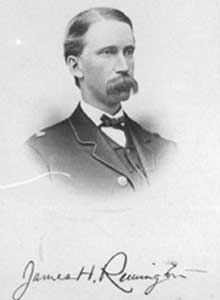

In the final days of the Civil War, the U.S. Congress established an agency within the War Department that was to have far reaching powers in terms of setting social policy in the war-ravaged South. The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands was authorized to supervise the “management of all abandoned lands, and the control of all matters relating to refugees and freedmen from rebel states.” Bureau agents were directed, among other things, to establish schools, provide aid for the destitute, and settle legal disputes between white landowners and former slaves. One of the bureau’s agents was Rhode Islander James H. Remington.[1]

Remington was born on the family homestead in Warwick, Rhode Island on November 9, 1838, the son of Benjamin and Sarah (Tillinghast) Remington.[2] After attending East Greenwich Academy, in 1862 he graduated from Brown University as the class valedictorian. Like many of his classmates, Remington enlisted in the Union Army after graduation. Remington was mustered into Company H, of the Seventh Regiment of Rhode Island Volunteers, on September 4, 1862. The newly commissioned captain would soon face the horrors of war. On December 11, less than four months into his military career, the Seventh Regiment was engaged in the Battle of Fredericksburg. The Union forces under the command of Rhode Islander General Ambrose Burnside launched a frontal assault on the Confederates’ entrenched positions. The outcome was disastrous for the Union Army. When it was over, the Seventh Regiment lost nearly 200 men killed, wounded, or missing in action. Among the wounded was Remington who suffered a shattered jaw. The wound was so severe that the bone could not be set and he was disfigured for the remainder of his life. The Seventh Regiment would go on to fight in many battles over the next three years throughout the South but Remington’s fighting days were over. He was discharged onMay 2, 1863.[3]

Once discharged, Remington returned home to Rhode Island where he was soon elected to the General Assembly as a Representative from Warwick. His time back in Rhode Island was, however, short lived. Upon receiving a commission as a captain in the Veterans Reserve Corps he resigned his legislative position in the General Assembly and reported for duty. After several duty stations he was assigned to guard Confederate prisoners of war at Camp Chemung in Elmira, New York. Here in his spare time he studied law and was soon appointed as a Judge Advocate. His judicial experience proved of great use for the remainder of his life. In 1866, following the end of the war, Remington was assigned to serve as an officer in the newly formed Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands in Norfolk, Virginia.

Remington’s papers at the Rhode Island Historical Society provides scholars with an example of one of the most contentious issues during the Reconstruction period—the battle over control of southern lands.[4] In early 1864, Union forces under the command of General Benjamin Butler took “possession” of a sizeable farm on the Virginia coast near the city of Norfolk owned by William E. Taylor, a wealthy lawyer and farmer. Despite a considerable cloud of controversy dealing with his actions while in charge of New Orleans, Butler had been given command of the district that included Norfolk in November 1863. Taylor, an unrepentant secessionist, had served at one time in the Confederate Army and later clerked in the Confederate War Office in Richmond. Remington’s records indicate that from September 1865 to December 1866, the federal government paid Taylor rental income ($118 per month), compensation for firewood, and remuneration for fisheries. Despite Butler’s repeated overtures, Taylor refused to sell or rent the land. The land was formally “restored” to Taylor in late January 1867. After this time the Bureau was no longer “responsible for rent” or “damages” to the property. However, the hundreds of black residents (one estimate put the number at 500) had no desire to leave. Taylor refused to sign the order restoring his land until it was “wholly free from freedmen and their families.” Taylor told a court of inquiry that “before he would treat them as citizens entitled to any rights under the law he would see them in hell.” The Bureau urged Taylor to draft fair labor contracts. As one agent put it, Taylor was trying to “wreak vengeance on better men than he ever was, and better men than he ever could be because they were loyal to their government.”

In February 1869, Richard Parker and Henry Black, two African Americans living on the land, were ordered to appear before the Norfolk County Court on a trespass complaint. They had repeatedly ignored removal orders. The following month, Butler, now a Congressman from Massachusetts and a strong advocate for civil rights, wrote a letter to the general in charge of the vicinity around Norfolk informing him of the history of the Taylor farm. While Taylor was “absent shooting our soldiers, I took possession of his farm on behalf of the United States,” wrote Butler and “put on that farm a number of men and women whose fathers and brothers were off fighting our battles.” They “built up their little cabins and cultivated their little patches of ground and became honest and good citizens, which Taylor can never become.” Butler argued that the freedmen’s cultivation of the land gave them a right of ownership or at the very least a right to strike up a fair contract with Taylor to continue to farm it. What was important to Butler was “loyalty.”

The Massachusetts Congressman called for the trespass case to be removed to U.S. District Court under the 1864 Civil Rights Act. Butler, a trained lawyer, was fully aware of the massive expansion of the jurisdiction of the federal courts since 1863. The former Union general, who famously refused to return slaves that reached his lines at Fortress Monroe in Virginia in the opening days of the war, noted that he “instituted proceedings for confiscation” of the Taylor farm, but the orders “were not carried out because Andrew Johnson became President by assassination.”[5] Heknew that the former slaves living on the farm were not going to get a fair hearing in a state court. Since the land had just been planted, Butler urged that the occupants be allowed to harvest. He pleaded with the Bureau to ensure that “the poor people upon the land to which they have much more equitable if not legal right than Taylor” should stay “until they can reap” what they had “sown.” This was the only thing “right in the sight of God and man,” proclaimed Butler. Unfortunately, what Butler deemed to be right did not play out in the end. The vast majority of African Americans on the Taylor farm were removed. The Freedmen’s Bureau, fearful of a backlash, failed to act.

As Remington’s papers indicate, the Freedmen’s Bureau was a vital first step in elevating former slaves to full citizenship. It was indeed an organization, to borrow a phrase from historian Janette Thomas Greenwood, which helped provide the “first fruits of freedom.”[6] However, the Bureau was woefully undermanned and was eliminated by Congress in 1872. In 1868, while still in the service of the Bureau, Remington married Ellen Howard of Brooklyn, New York, and once the Bureau was disbanded the couple moved to New York City. Although Remington was well suited to deal with civil rights cases he devoted the remainder of his professional career to tax, patent and real estate law. He died in New York City in 1899.

[Banner Image: An officer of the Freedmen’s Bureau acts as peacemaker. Published in Harper’s Weekly, July 25, 1868 (Library of Congress)]Footnotes:

[1] See James H. Remington Papers, “Historical Notes,” Rhode Island Historical Society.

[2] One of the unusual side notes regarding the Remington homestead is at the time of James’s birth it had been in the same family since its original purchase from the Narragansett Indians.

[3] William P. Hopkins, The Seventh Regiment Rhode Island Volunteers in the Civil War 1862-1865 (Providence, RI: The Providence Press, 1903), 353-354.

[4] See James H. Remington Papers, box 6, folder 15, Rhode Island Historical Society.

[5] Benjamin Butler to General E. R. S. Canby, March 22, 1869, James H. Remington Papers, box 6, folder 15, Rhode Island Historical Society.

[6] See Janette Thomas Greenwood, First Fruits of Freedom: The Migration of Former Slaves and Their Search for Equality in Worcester, Massachusetts, 1862-1900 (University of North Carolina Press, 2010).