[Rhode Island politics in the late 1800s and early 1900s was run by the Republican Party’s political machine. From 1884 to 1907, it was led with an iron fist by Charles R. Brayton of Warwick. The election of 1905 was so fraudulent and such a source of embarrassment for the state that critics of machine politics, including many in the Republican Party, finally rebelled. In early 1907, Brayton’s pick for U.S. Senator, Colonel Samuel Pomeroy Colt, did not receive the necessary votes in the legislature to be elected. This article from The New York Times, published on July 14, 1907, counts Brayton being forced off the Republican Party’s Executive Committee as the end of Brayton’s reign. The declaration of the end of Brayton’s power was, however, somewhat premature. Brayton did finally depart the Sheriff’s Office in the State House in early October 1907. But in November 1907,he was elected to the Republican Party’s State Committee, and the next year he attended as a delegate the Republican Party national convention in Chicago. Brayton died in September 1910. In this age, newspaper articles often had lengthy headlines. For this article, they are as follows: “Brayton, the Blind Boss of Rhode Island. Downfall of Republican Leader in Smallest New England State Ends a Picturesque Personality. In Ways that Resemble Those for Which ‘Old Hickory’ [President Andrew Jackson] was Famous He has been Sustained.” This description of Brayton and his methods and power is amusing and revealing, though the author of the article, by today’s standards, is insensitive to Brayton’s eye sight problems and in one jab inappropriately insults recent immigrants in the state.]

The resignation of Charles R. Brayton, the “Blind Boss” of Rhode Island, from the Executive Committee of the Republican organization of that State, is regarded by some as the final collapse of machine rule in Rhode Island. There are some others who see in this resignation a fatal lack of completeness, inasmuch as the “boss” who had so long conducted the political destinies of the State still remains a member of the -Republican State Central Committee, and is also the Rhode Island member the Republican National Committee.

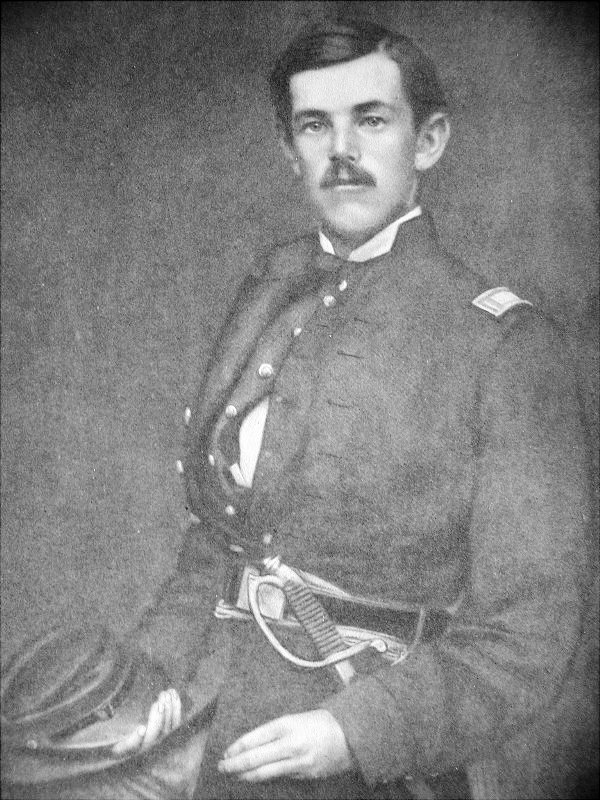

Charles Brayton left in the middle of his sophomore year at Brown University to join the 3rd Rhode Island Heavy Artillery Regiment in the Union Army in the Civil War. By war’s end, he was a colonel.

But all agree that Brayton is headed in the right direction and that his resignation from the Executive Committee marks the final collapse of the old Republican machine and the eventual passing from power of one of the most autocratic and picturesque of political dictators. For more than a quarter of a century this king lobbyist of Rhode Island had exercised his power and had worn his crown, or rather wielded his whip, with as much indifference to public condemnation as was displayed by the late Mr. Tweed when he asked-his famous question of “What are you going to do about it?” And the one-poor comfort that Rhode ‘ Islanders had was the knowledge that the recognized ruler of the Republican organization in the State, the “boss” who dictated party nominations and controlled elections, influenced legislation and who received Representatives, Senators, and corporation agents on equal terms, the one lone consoling thought of those whom Brayton ruled so autocratically and so long was that the “boss,” unlike many others, was at least a native born.

College bred and a brilliant soldier, the tall, gaunt form of the “Blind Boss” of the little New England State is as picturesque a-figure as any that ever strode through the gloom of feudal days. A master of secret intrigue and an open agent of political corruption, stout apostle of republicanism, and a stern believer that any means warranted the end, so long as that end was to the good of his party, his followers and himself, an implacable enemy and an unswerving friend, a stanch ally and an open foe, of him it might well have been written that

His honor rooted in dishonor stood,

And faith, unfaithful, kept him falsely true.

Had not blunt “Old Hickory” set the political standard that “To victor belongs the spoils” this political freebooter of New England doubtless would have run up the Jolly Roger on his ship of spoils and with it the skull and cross bones which tell of no quarter to the vanquished. And for nearly thirty years it would have flown, a baneful emblem to all who believe in the integrity of the ballot box, the incorruptibility of legislators, and in clean government and decent politics.

Brayton believed in none of these. His faith was in himself and the Republican party. No better insight into his character and his methods could be had than is afforded by a reminiscence of D. L. D. Granger, a Democrat and who for eleven years was Treasurer of Providence and for two years that city’s Mayor. When Granger was Mayor of Providence, he saw in in his paper one morning an announcement that a hearing would be given at the State House that afternoon on an important constitutional amendment, then pending in the Senate. This amendment vitally affected the interests of Providence, and the Mayor made it a point to be on hand, and went to the hearing accompanied by the City- Solicitor and whose duty it was to oppose all measures which had not previously been submitted to the City Council.

The Mayor and the Solicitor found the Senate Committee in session and in attendance several of the Providence members of the House. Granger asked them what they knew about the bill, and they confessed that they knew nothing about it, nor did they know on whose request it had been introduced. The Mayor therefore asked that a public hearing be given the amendment, that ail concerned might be afforded an opportunity of studying its features.

It was at this moment that the “Blind Boss” was led into the room.

“Who is here?” he demanded. The Chairman informed him, enumerating all that were present, the “Blind Boss” keeping account on his fingers. When the Chairman’s roll-call was ended Brayton missed one of his henchmen and asked if he was there. The Chairman said he was not.

“Well, he will hear from me,” Brayton is reported to have replied. Then, according to the story, Brayton groped his way to the Mayor and said to him: “There is no use in your -corning here. Every member of the Legislature from Providence is pledged to this amendment, and they are going to vote for it. It is for the benefit of the Republican party, and it is going to pass.”

And it did. The amendment went through both houses of the General Assembly, as Brayton had said it would, but fortunately it was defeated at the next election, when the measure went before the people. But the significance rested in the fact that a political boss, holding no office, could stand up in a committee room of a Senate and openly declare that he was having a constitutional amendment passed solely for the benefit of the party to which he was allied.

The political history of Rhode Island in recent years affords numerous other spectacles of entrenched iniquity. Brayton was frankly the agent and attorney of corporations. And that he did not hesitate to discipline even his employers is shown by his action in allowing the ten-hour law for employees of street railways to become a law. One reason that has been advanced for his wholly unexpected move in this direction is that he had had some friction with his corporation clients, and that the measure which he caused to be enacted Into a law was a purely disciplinary one and enacted for the purpose of convincing the street railway corporations that they must not become refractory.

This act decreed that “a day’s work for motormen and conductors should not exceed ten hours’ work, to be performed within twelve consecutive hours,” and further provided “that on all legal holidays and on occasions when an unexpected contingency arises demanding more than the usual service . . . and in case of accident and unavoidable delay, extra labor may be performed for extra compensation.”

The law was passed and immediately the street railway companies became furious. But all of their storming and protesting was of no avail. The law became operative, and they refused to obey it. Ensued a long and bitter strife between employers and employees, and as a final outcome the State troops were called out and martial law was proclaimed in all of the disturbed districts. The strike eventually failed, and the defeated strikers went back to work, but not until the law had been successfully derided. Fearing another outbreak of the kind, the corporation appealed to the courts, pleading that the law struck a blow at the freedom of contract. But whether or not Brayton’s power reached to that end, the validity of the law was upheld by the court, and nursing their much-wrung withers, the street railway companies had then no other resource than to placate, if possible, the man who had caused them so much woe. It appears that they succeeded in making their peace with the “boss,” for at the next session of the Legislature the law was virtually repealed.

Thus by hook or by crook, by fair means or foul, Brayton waged his war and attained his ends. In an interview which was given to a correspondent of the New York Evening Post some time ago, and which is so amazingly frank in its nature as to have moved the reform element of Providence to reprint it in pamphlet form for general distribution, the “Blind Boss,” in reply to a question asking what was his share in the forming of legislation, is said to have replied:

“I am an attorney for certain clients and look out for their interests before the Legislature. I am retained annually by the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad Company, and am usually spoken of as ‘of counsel’ for that road. Of course, I do not have anything to do with damage suits or matters in relation to grade crossings and other questions where legislation is necessary. As everyone knows, I act for the Rhode Island Company (street railway interests), and I have been retained in certain cases by the Providence Telephone Company. In addition to these I have had connections, not permanent, with various companies desiring franchises, charters, and things of that sort from the Legislature. I never solicit- business. It comes to be unsought. In managing the campaign every year, I am in a position to be of service to men all over the State. I help them to get elected, and naturally, many warm friendships result. And then when they are in a position to repay me they are glad to do it.”

There could probably be no better description of the man’s character than is contained in these frank admissions. But of the friends of which he boasts so much, it is hard to find them in Providence these days — perhaps the old story of the rats and the sinking ship. No more convincing proof that he -has finally decided to lay aside the burdens of boss-ship could be had than in this reticence of his old followers, men who- have seen the writing on the wall and are seeking new opportunities or alliances or perchance thinking of some way to live down the old.

As to the personality of this sightless despot who has so long dominated the political destinies of Rhode Island. One cannot but admire the indomitable courage of the man or withhold a sneaking admiration for his hardy vices. And there is probably as much of the old Adam in Rhode Island as there is elsewhere.

Also as many there who are willing to be led when a forceful. dominating, albeit an unscrupulous leader takes the lead. And like most leaders of men, the chief source of his power rested in the unquestioned loyalty to those who’ served him. Even his bitterest enemies do not say that he was ever unfaithful to a follower. His reputation is that of never breaking his word to a friend and never forgiving an enemy. And “right honestly he liked an honest hater,” but never more pleased than when he brought one of these to combat.

This trait of combativeness showed early in his career. Born Aug. 16, 1840, in Warwick, R. I., of an old Puritan stock, he, like the old Kingmaker from which the town takes its name, set out in his youth to deeds of arms. Sent by his parents to the Brown University in 1859, he quitted that institution in the first term of his sophomore year to recruit a company from his native town and to engage in battle with the people who had fired on Fort Sumter.

The company was enrolled in the Third Regiment of Rhode Island volunteers, an organization which was subsequently to be known as the Heavy Artillery. The young student of Brown College gained rapid promotion. He was commissioned a First Lieutenant in August, 1861, promoted to a Captaincy the following year, made a Lieutenant Colonel in 1863, and advanced to the rank of Colonel in April, 1864, a rank which he held when his regiment was mustered out of service after Lee’s surrender.

Brayton, during these smoke-blown days, participated In the capture of Port Royal, S. C., in the siege and reduction of Fort Pulaski, Georgia, in the battle of James Island, S. C. the capture of Morris Island, and the reduction of Fort Sumter.

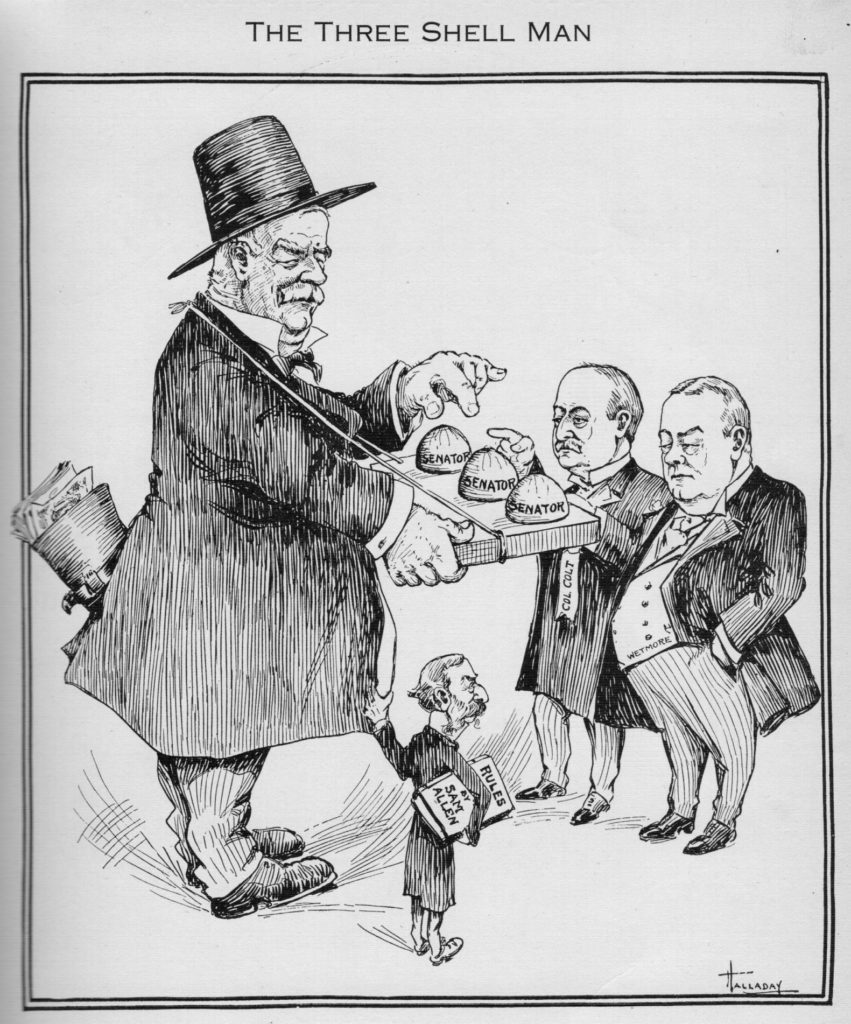

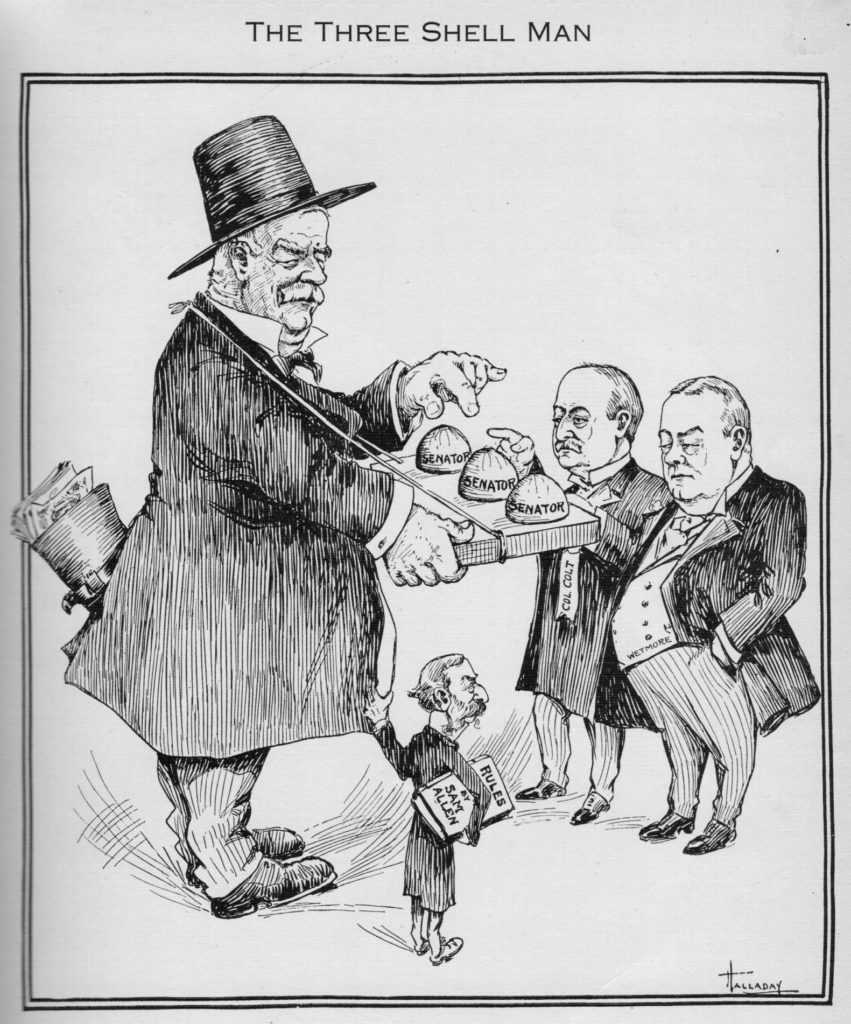

Cartoon showing Charles Brayton picking the Republican candidate for U.S. Senate in 1907, either newcomer Colonel Samuel P. Colt or incumbent George P. Wetmore. But, after 81 ballots by the General Assembly, Brayton could not push Colt through, which helped lead to Brayton’s downfall. By Edward Halliday and published in a 1914 book (Russell DeSimone Collection)

When the command was mustered out of service Brayton applied for and received a commission in the regular army, was appointed a Captain, and assigned to the Seventeenth Infantry. But the quiet days into which the army had fallen then was in no way suited to his taste, and he resigned soon after to be appointed Postmaster at Port Royal, S. C. From this post he moved from one political job to another, becoming a Collector of Internal Revenues, then a-Pension Agent, next a Trial Justice, and drifted from this to the office of Township Clerk in his native town.

In 1870, when Grant was President, he was offered the post of Consul to Cork, but declined it. Four years later he was appointed Postmaster at Providence, a position he held until 1880, when he resigned to take position as Chief of the State Police. From this post he became active in State politics, was shortly made Chairman of the Republican State Committee. And in 1890 was chosen as the Rhode Island member of the Republican National Committee.

From that time on his career has been so closely interlocked with the political history of Rhode Island that it would be difficult to separate the two. “I have been,” he asserts, “the scapegoat of my party. People have said all sorts of things about me, most of them lies, I am not as bad as I have been painted, but I do not care much what people say. What I have done has been for the benefit of the Republican party, and every time I have taken a retainer from any corporation I have always stipulated that I would drop the case if it turned out to be against the interest of my party.”

One would suppose that a man who had so absolutely dominated the State for so long a period, who had politicians, Legislatures, and corporations so much under his control that they could not call their souls their own, would be immensely wealthy, a man who could afford yachts, horses, and a Wantage in Ireland if he felt so inclined. But so far as any in Rhode Island know, it does not appear that he is possessed of much money, and it is not supposed that he has spent much, except in the furtherance of political deals. His “pile” is estimated by those who know him best at the modest figure of $100,000.

Brayton Is a Mason, and has been Commander of the Department of Rhode Island in the Grand Army of the Republic. He married In 1865, his wife being Miss Antoinette Percival Belden and who bore him two children. His daughter, Antoinette, born in 1869, married Henry B. Deming. She died in 1893, and her death prostrated the father with grief. The son, William Stenley Brayton, is employed by an electric company in New York.

It was in 1900 that Brayton-first had trouble with his eyes, cataracts, forming over them. The following year he went to Philadelphia, where a specialist operated on one eye. Blood poisoning set in, and it was necessary to take out the eye. Since then the other has been sol cloudy that its owner can barely see out of it, and for years he has been unable to read, an attendant doing this for him from place to place.

The “boss” is not and never was a church member. Nor was he -ever affiliated with Prohibitionists. By his desk is always a pipe, and he is most always enveloped in smoke.

As illustrating his political methods, it is related that he once became impatient at a long session of the House, and after waiting for his lunch until his patience had become exhausted, he summoned the Sheriff and ordered him to see to it that the House adjourned. It Is not known what methods the Sheriff employed, but it is a matter of record that. When Brayton reached his hotel the House was meekly following at his heels.

But his power has waned, if not broken altogether, and one is permitted to think what one pleases about the extent to which Rhode Island politics will be purified by his elimination. James H. Higgins, when he came to office as Democratic Governor of the boss-ridden State, found Brayton strongly entrenched as the accepted ruler of the Republican organization, and although holding no office having an office room in the State House. One of the new Governor’s first acts was to demand that Brayton be turned out of his occupancy of State property. Brayton only laughed, and so absolutely did he hold the mastery that despite the Governor’s insistence that he should be “expelled from the –capitol as a “public nuisance” and as a “moral and political pest” stayed in his old quarters. But his power has been fatally weakened. The first indication of his waning strength came when he failed to carry out his contract to elect Colonel Colt to the office of United States Senator from Rhode Island. Many of his henchmen rebelled, and this was the beginning of the end. Now it is announced that Colt will try again for the Senate when the comes, but without the aid of the once puissant “boss.”

[Banner Image: Cartoon showing Charles Brayton picking the Republican candidate for U.S. Senate in 1907, either newcomer Colonel Samuel P. Colt or incumbent George P. Wetmore. But, after 81 ballots by the General Assembly, Brayton could not push Colt through, which helped lead to Brayton’s downfall. By Edward Halliday and published in a 1914 book (Russell DeSimone Collection) ]