[This article is based mostly from the introduction by Patrick T. Conley appearing in Russell J. DeSimone’s recent book, Rhode Island Election Tickets: A Survey of Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Paper Ballots. The images are all from Russell J. DeSimone’s collection.]

This vast collection of Rhode Island printed election tickets, originally called “proxes,” so meticulously compiled by Russell DeSimone, can be best understood by reference to the development of Rhode Island’s colonial system of voting and office holding. These early political procedures were a very significant home-grown implementation of the colony’s Royal Charter of 1663, granted to it by King Charles II through the efforts of Dr. John Clarke.

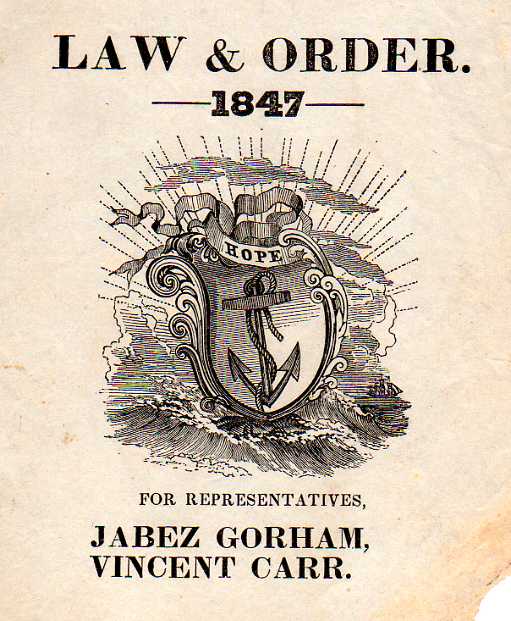

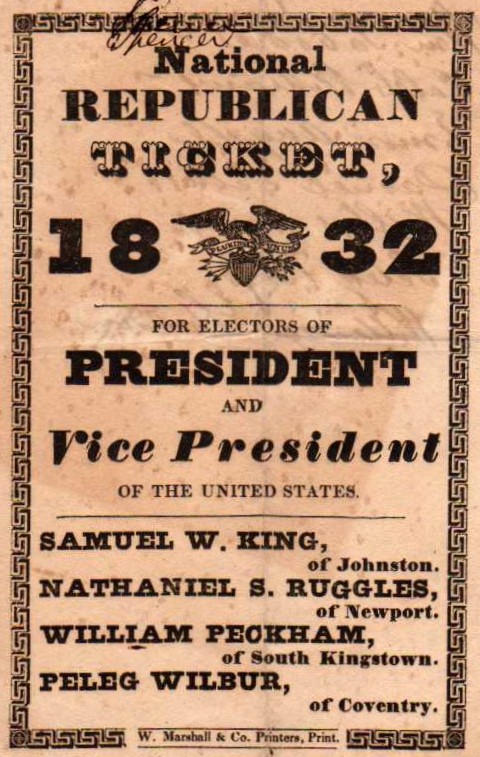

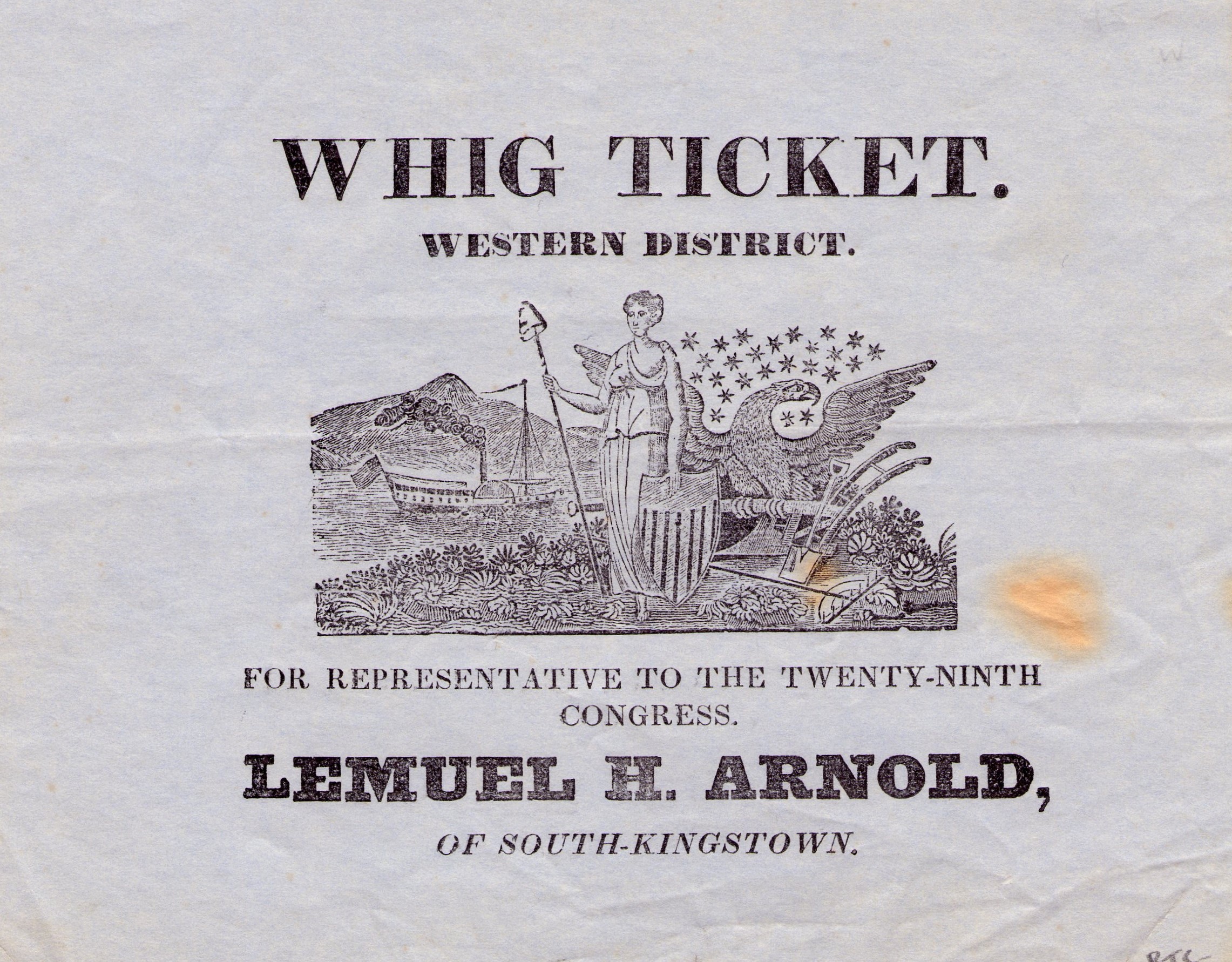

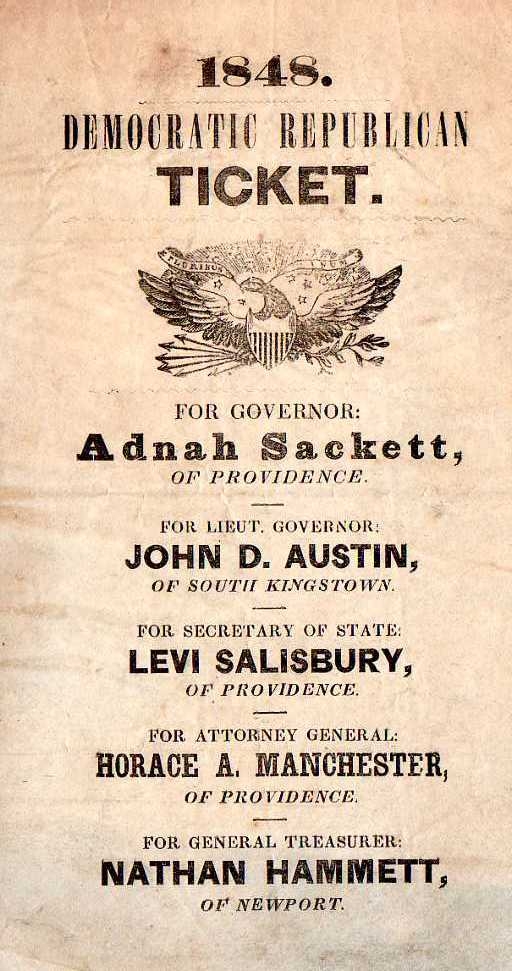

The first appearance of election tickets occurred in the mid-1740s, a time corresponding to the development of a political two-party system in Rhode Island, which authoritative historians regard as the first in America. These printed ballots, listing a full slate of statewide officers, facilitated and were a by-product of that development.

Rhode Island’s voting practices and the issue of town representation in the General Assembly continued after independence and statehood. They exerted the greatest impact on the nineteenth-century movement for political and constitutional reform—extending not only to the Dorr Rebellion of 1841-43 but well beyond it.

With the passage of time, these tickets were used for presidential elections, constitutional adoption, constitutional amendments (from 1843 onward), city and town elections, and a few important referenda.

By the late 1800s, however, the Industrial Revolution and the immigration it spawned had greatly enlarged Rhode Island’s population making the ticket system unwieldy. Also contributing to the ticket system’s demise on the state level were the expansion of suffrage by the Bourn Amendment of 1888 and the implementation of the Australian secret ballot system, a reform that was adopted permanently in 1889.

Although these modernistic developments caused the abandonment of election tickets in state elections, they did not change human nature. In 1905, muckraker Lincoln Steffens wrote a national expose in Scribner’s Magazine that described Rhode Island as still “A State for Sale.” The method of voting may change, but a newer system cannot, for long, ward off its abuse by the human drive for power.

******************************************

Contrary to widely held opinion, the Royal Charter of 1663, Rhode Island’s basic law, did not establish a specific suffrage requirement. It simply empowered the Assembly to “choose, nominate and appoint” freemen of the colony. However, both the framers and recipients of the charter apparently considered the franchise a privilege to be exercised only by those who had been elevated to the status of freemen, and indeed such was the practice in both the towns and in the colony prior to 1663. Thus, under the Royal Charter, freemanship remained a prerequisite for voting, and the colonial legislature in 1664 declared “that none presume to vote…but such whome this General Assembly expressly by their writing shall admitt as freemen.”

In 1665 visiting royal commissioners informed Rhode Islanders that it was his “Majestyes will and pleasure” that an oath of allegiance be taken by every householder in the colony and that “all men of competante estates and of civil conversation, who acknowledge and are obediente to the civil magistrate, though of differing judgements, may be admitted to be freemen, and have liberty to choose and to be chosen officers both civil and military.” The Assembly promptly responded to the commissioners’ suggestions by enacting a statute which enabled those of “competent estates” to become freemen of the colony after taking a prescribed oath. Those not admitted to colony freemanship could not vote for “publicke officers” (i.e., governor, deputy governor, and assistants) or deputies, nor could they hold colonial office themselves.

Many historians have failed to realize that a distinction existed between freemen of the towns and freemen of the colony, because most freemen had dual status. The town freeman was empowered to vote for local officials such as the town council, sergeant, constable, and treasurer, but the suffrage statute of 1665 withheld from one who was only a freeman of a town the privilege of selecting deputies to the colonial Assembly. This restriction was not permanently removed until 1723. In addition, a man who was merely a town freeman could not vote for general officers of the colony. An act of 1760 clearly stated that such votes were invalid and “shall be rejected and thrown out.”

According to the statute of 1665, a person became a freeman of the colony either by direct application to the Assembly or through being proposed by the chief officer of the town in which he lived. In the early years, some who petitioned the Assembly directly were not town freemen. A few were inhabitants of unincorporated territory, such as the Block Island petitioners of 1665, while some held their land elsewhere in the colony than the town in which they resided. A person who was only a freeman of the colony was prohibited by statute from voting for local officials.

In the normal course of events, however, Rhode Islanders secured dual freemanship. They gained the right of inhabitancy and acquired a “competent estate” in the town where they had chosen to reside. Then they applied and were admitted to town freemanship by their fellow townsmen of that status, and finally their names were proposed or “propounded” to the General Assembly for admittance as freemen of the colony by the town’s chief officer or the town clerk. When a town freeman was proposed to the Assembly in this manner, his acceptance as a freeman of the colony was practically assured. Once approved, his name was entered in the records of the colony.

In 1723 a statute was passed by the Assembly, which set the first specific landed requirement for town freemanship and, since that status was the usual and nearly automatic prelude to colonial freemanship, the act is worthy of citation. This law stipulated that a person must be a “freeholder of lands, tenements, or hereditaments in such town where he shall be admitted free, of the value of one hundred pounds, or to the [rental] value of forty shillings per annum, or the eldest son of such a freeholder.”

In 1729 the real estate requirement was increased to $200, in 1746 raised to $400, but by 1760 it had been reduced to $40 (ca. $134). These drastic and erratic changes were more the result of inflationary and deflationary trends than of the stringency or fickleness of the General Assembly.

The changes in land valuation requirements were often accompanied by provisions designed to eliminate fraud and election abuses. Since many people continued to vote after they had disposed of the property upon which they had been admitted, legislation was enacted in 1742 and 1746 to ban this practice and other types of chicanery.

The last reform and revision of the colonial franchise laws in 1762 attacked further irregularities by denying the vote to those who owned only houses or tenements, but not the title in fee simple to the land upon which the structure stood. It also denied the franchise in the right of a wife’s dower. Finally, this law was the first to specifically acknowledge the reserved right of townsmen to reject a freeholder proposed and duly qualified according to law. Henceforth, property did not ipso facto carry with it the right of admission.

Freehold requirements and suffrage stipulations enacted by the legislature could cause the uncritical reader to assume that the franchise was a privilege enjoyed by a select minority. Such an inference would be erroneous. The real estate requirement for freemanship was not a measure of oppression or restriction in a rural, agrarian society where land tenure was widely dispersed. The suffrage statute of 1746 declared that the manner of admitting freemen was “lax” and the real estate qualification was “very low.” Authoritative students of Rhode Island’s colonial history estimate that 75 percent of the colony’s white adult male population were able to meet the specific freehold requirements from the time of their imposition in 1723 to the outbreak of the War for Independence.

This fact, however, needs some qualification. Being allowed to vote and to hold office was not synonymous with exercising those privileges. Normally less than half the freemen bothered to vote, and those that did often elected to office men from the upper socio-economic strata. To coin a phrase, Rhode Island democracy was one of indifference and deference, but a democracy it was.

Although the incentive to participate politically was not widespread, it was strong in some quarters as evidenced by the development of a system of two-party politics in the generation preceding the American Revolution. Opposing groups, one headed by Samuel Ward and the other by Stephen Hopkins, were organized with sectional overtones; generally speaking (though there were notable exceptions), the merchants and farmers of southern Rhode Island (Ward) battled with their counterparts from Providence and its environs (Hopkins). The principal goal of these groups was to secure control of the powerful legislature in order to obtain the host of public offices—from chief justice to inspector of tobacco—at the disposal of that body.

The semi-permanent nature, relatively stable membership, and explicit sectional rivalry of the warring camps has led historian Mack Thompson to describe the state’s pre-Revolutionary political structure as one of “stable factionalism.” Another historian, David Lovejoy, has boldly maintained that Rhode Islanders revolted from British rule not only “on the broad grounds of constitutional right to keep Rhode Island safe for liberty and property,” but also to preserve “the benefits of party politics”—patronage and spoils. Professor Jackson Turner Main, the authoritative historian of the American political party system, credits Rhode Island with its origins.

As noteworthy as the development of the party system in mid-eighteenth-century Rhode Island was, so too were the rules by which the political game was played. The charter provided the broad framework within which elections were conducted, but a succession of resourceful and imaginative politicians supplied the unique details through an intricate combination of custom and statute. Noted American political historian Richard P. McCormick has correctly observed that the salient and most significant feature of Rhode Island government under the charter “was that the crucial electoral arena was the colony–later the state–as a unit.” The governor and deputy governor plus a secretary, an attorney general, and a treasurer were elected annually in April on a colony-wide or at-large bases, as were ten “assistants” who comprised the upper house. Only the deputies, elected semiannually in April and August, were chosen on a local basis. Further, there was no county government: the county existed only as a unit of judicial administration. Thus, there existed an obvious inducement to form colony-wide parties in order to elect a full slate of general officers.

For these at-large contests, Rhode Islanders devised a peculiar system known as “proxing.” A “prox” was a ballot upon which a party placed the names of its at-large candidates. The elector in his town meeting on the third Wednesday in April took the prox of his choice (making any deletions or substitutions he deemed desirable) and signed it on the reverse side in the presence of the town moderator. The voter then submitted the prox to the moderator, and that official forwarded it to the town clerk to be recorded. When this ritual was concluded, the proxies were sealed in a packet and taken to Newport by one of the town’s state legislators for the start of the May session of the Assembly. On “election day,” the first Wednesday in May, ballots were opened and counted by the incumbent governor in the presence of the incumbent assistants and newly elected deputies sitting jointly in “grand committee.” The candidate having a majority of the total vote cast for his respective office was declared elected.

Under this system a party’s success was dependent on many procedural factors—on how widely its printed prox could be distributed, on how many new voters could be qualified by fraudulent transfers of land, on the number of electors of the opposite persuasion who could be induced by bribes to abstain from voting. Rhode Island was also a democracy of corruption and chicanery. The Rev. Andrew Burnaby perceptively observed in his travels through the colony in 1760 that the “men in power, from the highest to the lowest, are dependent upon the people, and frequently act without that strict regard to probity and honour, which ever ought invariably to influence and direct mankind.”

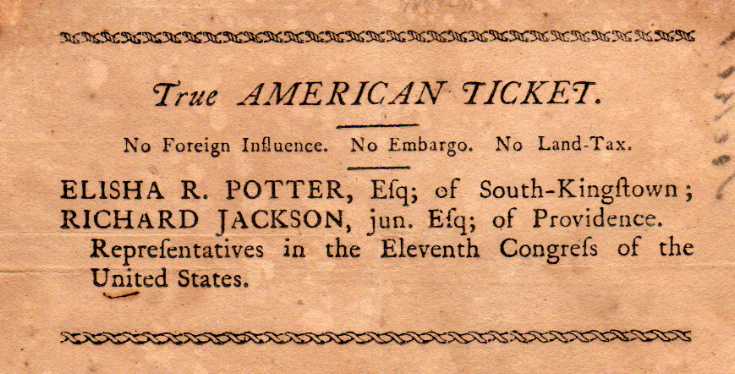

As mentioned, the freeman voting by submitting his prox signed the back of the prox and submitted it to the Town Moderator. When ballots were counted, the counter could, of course, see for whom the freeman voted. Thus, the ballot was not entirely secret. This allowed for some improper pressure to be potentially applied. In 1829, for example, an anonymous pamphleteer in a pamphlet entitled What a Ploughman Said, charged that prominent South Kingstown politician Elisha R. Potter controlled the votes of all those freemen who had borrowed money from him or from the bank he controlled (the Landholders Bank of Kingston village), or who had leased farmland from him. Whether this charge from a political opponent was true or not cannot be proved. But, as Christian McBurney found in his book A History of Kingston, R.I., in 1816, at least sixty men were obligated to repay loans to Potter and he hired at least seven tenant farmers; in addition, Potter did control the Landholders Bank. Thus, in an age before the enactment of a permanent secret ballot law in 1889, largely through the efforts of Charles C. Gorman, powerful politicians such as Potter had the means to punish those who were beholden to him but who did not vote his way.

Election tickets for Elisha R. Potter, Sr. to run for Congress around 1809 (before the War of 1812) and for his son, Elisha R. Potter, Jr., to run for Congress in 1843 (after the Dorr War in 1842). Both Potters won their elections. (Russell J. DeSimone Collection)

Rhode Island’s political antics, not to mention its autonomy, scandalized many a squeamish observer. In the eyes of the colony’s conservative critics, the land of Roger Williams, even on the eve of revolt, was “dangerously democratic,” according to eighteenth-century standards. Chief Justice Daniel Horsmanden of New York, in a 1773 report to the Earl of Dartmouth during the Gaspee investigation, disdainfully described Rhode Island as a “downright democracy” whose government officials were “entirely controlled by the populace,” and conservative Massachusetts Governor Thomas Hutchinson lamented to George III that Rhode Island was “the nearest to a democracy of any of your colonies.”

Because of such “democratic” conditions, no protests were made, nor reform measures attempted in the generation prior to the War for Independence, indicating dissatisfaction with the suffrage requirements or with the charter-imposed system of legislative apportionment. Rhode Islanders of the Revolutionary generation and their individualistic forebears were ever-mindful that they enjoyed near-autonomy within the Empire and broad powers of self-government within their colony. They were also keenly aware that their self-determination flowed in large measure from the munificent charter of Charles II. Thus, they harbored a passionate attachment for the document and defended it against all comers. They allowed it to weather the Revolutionary upheaval and retained it as the basic law of the state until 1843—a point far beyond its useful life.

The election tickets presented by Russell DeSimone serve as channel markers guiding historians on their way through the turbulent political waters of the Ocean State.

******************************************

Some books mentioned in this article or for further reading:

Patrick T. Conley. Democracy in Decline, Rhode Island Constitutional Development, 1776-1841. Providence: Rhode Island Historical Society, 1977, republished by the Rhode Island Publications Society, 2019.

Russell J. DeSimone. Introduction by Patrick T. Conley. Rhode Island Election Tickets: A Survey of Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Paper Ballots. East Providence: Rhode Island Publications Society, 2023.

David S. Lovejoy. Rhode Island Politics and the American Revolution, 1760-1776. Providence: Brown University Press, 1958 (second printing 1969).

Christian M. McBurney. A History of Kingston, R.I., 1700-1900, Heart of Rural South County. Kingston: Pettaquamscutt Historical Society, 2004.