Lieutenant General Jean Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur Comte de Rochambeau (1725–1807) did not simply wake up on the morning of June 18, 1781 and order his army of more than 6,000 men to break camp and begin their march south. Such an operation took months to plan and execute. He was already making plans and purchasing horses, wagons and foodstuffs by April 12, 1780.[1] He sent assistant quartermaster Matthieu Dumas ahead of the army to select the camp sites and to mark the route.[2] Dumas submitted his recommendations to Pierre François de Béville (1721-1798), Quartermaster General of the Army, for his approval and final decision.

Quartermasters are generally not well-appreciated. Officers usually do not want to perform these functions because there is no glory in them. After Congress appointed Nathanael Greene (1742–1786) to replace Thomas Mifflin (1744–1800) as quartermaster general of the Continental Army on March 2, 1778, Greene complained to his friend, General Alexander McDougall (1732–1786) on March 28: “All of you will be immortalizing your selves in the golden pages of History while I am confined to a series of druggery [drudgeries] to pave the way for it.”[3] He later wrote to General Washington on April 24, 1779 to express his desire to achieve fame on the battlefield, saying “Nobody ever heard of a quarter master in history.”[4] However, quartermasters perform essential functions to keep an army in the field.

Quartermasters were staff officers who were responsible for the procurement and distribution of food, clothing and supplies. They also reconnoitered travel routes and oversaw the repair and maintenance of roads and bridges, the organization and construction of camps, the supply and maintenance of wagons, and the teams of horses and oxen. They even assembled boats for water transport and river crossings.[5]

Quartermaster General Béville had five aides: Alexandre-Théodore-Victor, comte de Lameth (1760-1829); Jacques Anne Joseph le Prestre, comte de Vauban (1754-1815); Hans Axel, comte de Fersen (1755-1810); Louis François Bertrand Dupont d’Aubevoye, comte de Lauberdière (1759-1837); and Mathieu Dumas (1753-1837). Louis Alexandre Berthier (1753-1815) was also attached to the corps of quartermasters but most of his job was spent mapping the routes and the camps. (Berthier made some outstanding maps of Newport and Aquidneck Island.)

It does not appear that Béville or Vauban kept diaries. Lameth’s memoirs[6] say very little about his time in America. There is a brief (four-page) section on the siege and surrender of Yorktown that offers nothing new to our knowledge of those events. The Comte de Fersen’s journal[7] contains a series of letters to his father during the American campaigns. He wrote frequently during the garrison period. His last letter before the march to Yorktown is dated June 3, 1781. His next letter, dated October 23, 1781, apologizes for not writing sooner because he “had no time to write you the slightest detail.” He then includes a “Journal of Operations during the Siege and Surrender of Yorktown” (five and one-half pages) and another letter of the same date (one and one-half pages) that gives a brief account of the major events of the previous three and a half months.

Louis François Bertrand Dupont d’Aubevoye, comte de Lauberdière,[8] Louis Alexandre Berthier,[9] and Mathieu Dumas[10] are the only French assistant quartermasters general to have kept any detailed account of their work and travels during the march from Newport to Yorktown.

Disappointments

As the French army began preparing for its departure in early June 1781, General Rochambeau ordered a detachment of 400 men (100 from each regiment) to remain in Newport under the command of Lieutenant General Claude Gabriel Marquis de Choisy (1723-1800) to protect the city and the French ships and to guard the siege artillery.[11] Choisy also commanded about 1,000 militiamen, mostly from Massachusetts and Rhode Island.

Some Frenchmen who remained in Newport were not happy with their assignments. Soldiers who had not seen combat in over a year were anxious to engage the enemy, attain glory and establish their reputations. Thus, it is not surprising that some were disappointed when they were ordered to remain behind.

Denis-Jean-Florimond Langlois de Montheville, marquis du Bouchet (1752-1826)[12] was one of these disappointed officers. He perceived his new orders as a humiliation. General Rochambeau tried to revive his spirits by telling him that the artillery would rejoin the army at a later time and that the main army could capture nothing without de Choisy’s detachment. Still, du Bouchet felt shame at the thought of the army marching to combat while he remained in the rear.

Believing himself bereft of honor, his dejection made him incapable of listening to reason. He admitted he was on the verge of insanity. General de Choisy invited him and the Count de Lauberdière to dinner one evening in early June. When Lauberdière learned that du Bouchet would not be accompanying the army on its march, he surmised du Bouchet would not need his horses. Accordingly, during the dinner, Lauberdière asked to buy them.

Lauberdière was General Rochambeau’s nephew and aide-de-camp. At 21-years old, he was the youngest member of Rochambeau’s staff. Du Bouchet was seven years older and a brigade major of the army. He was also the brother-in-law of Irishman Thomas Conway (1733–1800), who once held a post in the French army but then had served as a major general in the Continental Army.

Du Bouchet perceived Lauberdière’s offer as irony and mockery and believed it was intended to humiliate him and to remind him of his disgrace. He became very angry and responded with bitterness and resentment. Feeling his honor had been attacked, Lauberdière could not ignore the response in silence. He returned an hour later with Mr. de Mauduit[13] to demand satisfaction and introduced Mr. de Mauduit as his witness.

Du Bouchet said he was extremely busy preparing orders for the army’s departure. He asked these men to be seated for about half an hour or so, after which he would be free and entirely at their disposal. He told them that he knew that certain wrongs could not be repaired and agreed to a duel with Mr. Lauberdière, who was younger and “had to make his reputation even more than I did.”

The duel left both men injured and unable to perform their duties for several weeks. Du Bouchet’s duties were assumed by another brigade major and Lauberdière had to find his own means to rejoin the army when he was well enough to travel.[14]

The Fleet

When Charles Louis d’Arsac, Chevalier de Ternay (1723-1780) died on December 15, 1780 (a gravestone in Trinity Church in Newport remains today to mark his death), his second-in-command, Charles René Dominique Sochet, Chevalier Destouches (1727-1794), assumed command of the French fleet until Admiral Jacques Melchior, Comte de Barras (1719–1793) arrived to officially take command. The Count de Barras arrived in Boston on May 8, 1781 aboard the frigate Concorde and assumed command of the fleet when he arrived in Newport on May 13.

While Rochambeau was preparing to march south, de Barras wanted to stay in Newport. He planned an expedition to the Penobscot and Nova Scotia to secure French fishing rights. Rochambeau wisely reminded the admiral that his fleet’s mission was to provide direct assistance to America and that the commander should only act in concert with General Washington and him (Rochambeau). When there was nothing planned, Rochambeau added, he could attempt to make an expedition to the North, but that was no longer the case as two councils of war were held aboard his ship to decide the upcoming course of action.

If de Barras had continued in his plan, de Choisy would have been unable to board his troops and munitions. These were vital additions to Rochambeau’s marching soldiers. De Barras understood the importance of the matter and responded that he would have the munitions, the artillery, and supplies loaded without delay and that he would leave Newport to join Admiral François Joseph Paul Comte de Grasse (1722–1788) when de Grasse sailed for the Chesapeake.

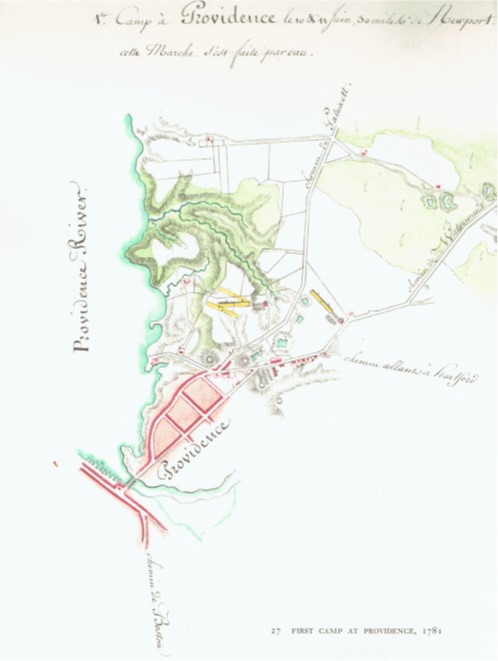

New warehouses were erected in Providence and the main French army depots were established there. Supplies and the army’s effects were brought to Providence by water from June 1 to 3.[15]

The First Phase of the March

Rochambeau’s troops departed Newport in four divisions a day apart beginning on June 18. Each division was organized by regiment in order of seniority and had an assistant quartermaster assigned to it. Part of the field artillery also went with each regiment.[16]

The first division began to march at 4 a.m. It consisted of the Bourbonnais Regiment and most of the general staff under Rochambeau’s command. The Vicomte de Rochambeau was their assistant quartermaster.

The second division, consisting of the Royal Deux Ponts Regiment, left the following day under the command of the Baron de Viomenil,[17] Rochambeau’s second in command. The Comte de Lameth was the second division’s assistant quartermaster.

The third division, consisting of the Soissonnais Regiment under the command of the Count de Viomenil,[18] departed on June 20. This division’s assistant quartermaster was Georges Henri Victor Collot (1750 –1805).

The Saintonge Regiment, commanded by the Comte de Custine,[19] formed the fourth division and set out on the 21st. Louis Alexandre Berthier was its assistant quartermaster.

Matthieu Dumas was the assistant quartermaster accompaning Lauzun’s Legion, which was then camped at Lebanon, Connecticut.[20] Lauzun’s Legion patrolled about ten miles to the left of the marching column. The chasseur (light infantry) companies of each regiment patrolled the flanks of the columns in order to scout and eliminate snipers, enemy patrols and other annoyances.

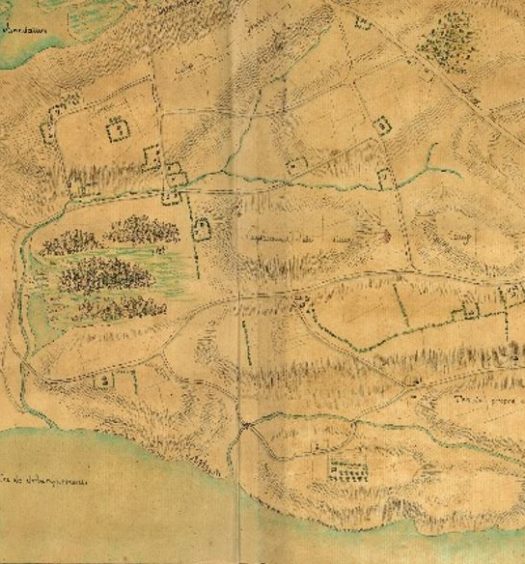

The troops usually rose at 2 a.m., broke camp, and were on the march by 4 a.m. They stopped for breakfast around 8 a.m. and halted around noon or 1 p.m. to make camp. After setting up the tents, the soldiers cut the wood they would need to burn for cooking and they fetched water. The soldiers also constructed ordinaries (kitchens) and dug necessaries (latrines). If they were camping for any length of time, they would also build slaughterhouses[21] and ovens. The baggage and artillery might arrive about eight to twelve hours later, if they arrived at the camp at all before the soldiers had departed.

The soldiers were often tired from pulling wagons the horses refused to pull. They might be soaking wet from perspiration or from rain, without tents, and had to spend the night in bivouac.[22]

The troops sometimes took alternate routes to accelerate the march or to reduce the demands on the local infrastructures. This was particularly notable in the march through Pennsylvania and Maryland. The Count de Lauberdière took half the army across the Susquehanna River by the more common route, crossing at Lower Ferry.[23] Matthieu Dumas took the baggage, artillery and the other half of the army by way of Bald Friar’s Ferry.[24]

The roads were often very poor, causing frequent breakdowns and damage to the wheels of the baggage wagons and cannon carriages. This resulted in delays while waiting for repairs to be made or for the damaged vehicles to rejoin the regiment. Bridges were sometimes damaged.

Food supplies were sometimes not delivered to the prescribed depots on time, causing further delays. Other times, not enough boats had been acquired for crossing the rivers, so the soldiers resorted to bringing boats with them.

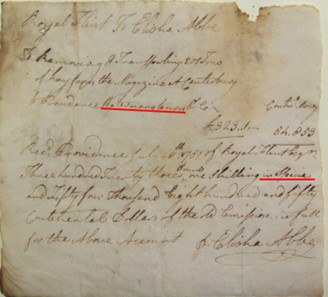

Here is a listing of food and grain to be supplied to each campsite:

Newport, 28 April 1781

20 Tons of Hay

20 Tons of Straw

380 Bushells Indn Corn;

If Oats are given to the horses then

225 Bushells of Oats

230 Bs Indn Corn

25 Cattle

12 Sheep

6 Calves

25 Cords Wood

To be supplied at every campsite[25]

Fig. 3. Supplies were to be transported from magazines such as the one at Canterbury, CT to camp sites such as Providence and Waterman’s Tavern.

Weather was another impediment. Rain and excessive heat hindered the march. Soldiers often had to camp in bivouac (in the open) when the baggage wagons were delayed. For example, after camping at Phillipsburg, New York, for nearly a month, it took the army six days to travel 40 miles to Kings Ferry, a distance the soldiers might otherwise have completed in two days.[26]

The Second Phase of the March

When the army marched out of Phillipsburg, it marched as a single column,[27] but the Americans and French sometimes took separate routes. Washington and Rochambeau agreed to march south and Rochambeau requested de Barras to set sail from Newport and bring the artillery and his troops with him.[28]

Prior to departing Newport, Choisy sent about 100 French troops to Providence to guard that city. He embarked his detachment of 480 French infantry troops and 130 artillerymen at Newport on August 21 and 22. They sailed on the 25th and arrived in the Chesapeake on September 10 to join Admiral de Grasse’s fleet from the Caribbean.[29]

Verger’s journal provides one of the few surviving accounts of the passage from Newport to Virginia with de Barras’s naval squadron. Other journals covering the same ground include those of du Bouchet, Vicomte Maurice de Villebresme,[30] Georges Alexander Cesar de Saint-Exupéry,[31] an officer in the Sarre-Infanterie,[32] and Marie François Joseph Maxime, Comte de Cromot du Bourg.[33]

The British and French fleets fought[34] two large battles in the Chesapeake bay region: the Battle of Chesapeake (March 16, 1781) and the Battle of the Chesapeake Capes[35] (September 5, 1781). The latter engagement gave the French control over the entrance to the Chesapeake Bay. It was arguably the most important naval engagement ever in United States waters.

Once de Barras’s fleet and de Grasse’s fleet from the Caribbean joined forces, the combined fleet blocked the Chesapeake Bay, thereby preventing any reinforcements coming to aid the Crown forces and preventing any possibility of the British army’s escape from the small port of Yorktown, Virginia. The allied forces assembled outside Yorktown and began the siege on September 28, cutting off supplies and any reinforcements by land. It eventually resulted in the British surrender on October 19. The French and American armies were pretty much equal in numbers but, with the addition of the French fleets, two-thirds to three quarters of the allied forces at Yorktown were French.

After wintering at Williamsburg, the French army marched back to Newport. There they rekindled the friendships they had made two years earlier. They then went to Providence on November 12, 1782 where they camped in bitter cold. Several soldiers died there and were buried in the North Burial Ground. The artillery departed Newport for Boston on November 18, followed by General Rochambeau on the 22nd and the rest of his army on the 23rd. The soldiers boarded French naval ships in Boston. Some of the troops were reassigned to French-controlled islands in the Caribbean. The remainder returned to France. Many of them would fight in the French Revolution.

Notes:

[1] Rochambeau to Washington April 12,1780. The Papers of Jean Baptiste Rochambeau. Library of Congress. Vol. 9, pp. 26-29. [2] Dumas, Mathieu, et al. Souvenirs Du Lieutenant Général Comte Matthieu Dumas, De 1770 a 1836: Publiés Par Son Fils. Librairie De Charles Gosselin, 1839. [3] The Papers of General Nathanael Greene. Edited by Richard K Showman et al. Published for the Rhode Island Historical Society by the University of North Carolina Press, 1976. Vol. 2, p. 326. [4] Ibid. Vol. 3, pp. 426-427. [5] Risch, Erna, and Center of Military History. Supplying Washington’s Army. Center of Military History, United States Army, 1981. Huston, James A. The Sinews of War: Army Logistics, 1775-1953. Office of the Chief of Military History, United States Army, 1966. [6] Lameth, Alexandre, and Welvert Eugène. Mémoires. Fontemoing, 1913. [7] Fersen, Hans Axel von. Diary and Correspondence of Count Axel Fersen. Hardy, Pratt, 1902. [8] Louis François Bertrand Dupont d’Aubevoye, Comte de Lauberdière’s diary is at the Bibliothèque Nationale and available at: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b52506900t/f17.image. It was translated into English as The Road to Yorktown: The French Campaigns in the American Revolution, 1780-1783. Edited by Norman Desmarais, Savas Beatie, 2020. [9] Berthier, Louis Alexandre. “Journal of Louis-Alexandre Berthier.” In The American Campaigns of Rochambeau’s Army, translated and edited by Howard C. Rice and Anne S.K. Brown. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1972. Vol. 1, pp. 221-282. [10] Dumas, Mathieu. Souvenirs Du Lieutenant-Général Cte Mathieu Dumas, de 1770 À 1836. C. Gosselin, 1839. Excerpts were translated into English as Memoirs of his Own Time; Including the Revolution, the Empire, and the Restoration. By Lieut.-Gen. Count Mathieu Dumas. London: Richard Bentley, 1839. However, neither of these documents covers his duties as quartermaster. That recently found manuscript can be read in the Journal of a French Quartermaster on the March to Yorktown June 16—October 6, 1781. Translated and annotated by Norman Desmarais. Lincoln, Rhode Island: Revolutionary Imprints (currently in press). [11] Heavy cannons were of various calibers: 12-, 24-, 36-, and 64-pounders, as well as howitzers and mortars of various calibers. The artillery park in Newport covered three modern city blocks. [12] du Bouchet, Denis-Jean-Florimond Langlois de Montheville marquis, Journal d’un émigré; ou cahiers d’un etudiant en philosophie qui a commencé son cours, dès son entrée dans le monde (Journal of an expatriate or booklets of a philosophy student who began his course, from his entry into the world). [13] Thomas-Antoine de Mauduit du Plessis (1753–1791). [14] Norman Desmarais. “A French Duel in Newport.” Online Journal of Rhode Island History. (February 19, 2022). At http://smallstatebighistory.com/a-french-duel-in-newport/ [15] Closen, Ludwig, Baron von. Revolutionary Journal 1780-1783, translated and edited with an introduction by Evelyn A. Acomb. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 1958. p. 82. [16] Ibid., 84. [17] Antoine Charles du Houx baron de Vioménil (1728-1792). [18] Joseph Hyacinthe du Houx Comte de Vioménil (1734-1827). [19] Adam Philippe, Comte de Custine (1740 1793). [20] Lauberdiere. op. cit. pp. 89-91; Berthier. op. cit. pp. 246-247; Dumas. Souvenirs. Vol. I, pp. 64, and 67-69. [21] The dressed carcass makes up about 60 percent of the live-weight of cattle; the remaining 40 percent live-weight is taken up by the hide, blood, bones, horns, hoof, tallow, intestines and casings, fat and organs such as the tongue, heart, kidney and liver (known as the Fifth Quarter). In December 1782, Jeremiah Wadsworth purchased 85 head of cattle on the hoof in Boston weighing 630 lbs. on average, leaving 350 lbs. of meat per animal. Jeremiah Wadsworth Papers, Box 144, Folder December 1782, Connecticut Historical Society. [22] Berthier. Op. cit. p. 245. [23] Now Havre de Grace, Maryland. [24] A bald-headed man named Fry supposedly kept a ferry at the ford. Both Bald Friar Ford and Ferry are said to have been named after him. George Johnston, History of Cecil County (Elkton, 1881), p. 345. The ford is 2 1/4 miles wide and 7 miles upstream from the present Conowingo Dam. This was the only practicable ford, but barely so, since the bottom was so rocky that the horses risked breaking their legs. 39.70482545436607, -76.2129786475943. [25] The potato yield in Rhode Island in 1778 was about 100 bushels per acre. The US average per acre yield increased to 1,025 bushels in 2011.The corn yield in Rhode Island for 1778 was 30 bushels per acre (a very, very good yield for the times). In 2011, the U.S. average was 225 bushels per acre. Some fields in Illinois grew as many as 280 bushels per acre. (One bushel of shelled corn was equal to about 40 pounds of cornmeal.) Soldiers were allotted 1.5 pounds of bread per day. An army of 5,000 French infantry soldiers would need 30,000 pounds of cornmeal in four days. That is equal to 750 bushels, or about 25 acres of corn (at 30 bushels per acre). Double that if the navy is included; in addition, even more corn was needed to feed the cattle and horses. Thus, the French army would need the equivalent of 400 acres of corn per month, or 800 acres if the navy is included.

The standard army wagon carried seven barrels (between 1,500 and 1,600 pounds of flour (1,200 to 1,300 rations). Thus, the 12,000 man army and navy required ten wagon loads of flour per day.

The average weight of a head of cattle was around 600 to 650 pounds but individual cattle could weigh as much as 1,000 pounds. David Trumbull in Lebanon, Connecticut, bought four oxen in December 1780. Their average weight was 634 pounds. He purchased a 600 pound ox on January 2, 1781. The next day he estimated the weight of two oxen at 1,050 pounds each, but one third waste (hide, tallow and bones). When Jeremiah Wadsworth bought cattle for the French forces in Newport in July 1780, he calculated it to “average 400 pounds each of Meat Beef,” i.e. slaughtered, about half the weight of a head of cattle today.

Every soldier was allotted 1 pound of beef per day: 5,500 soldiers x 30 days equals 165,000 pounds or 250-275 head of cattle per month.

The above information is courtesy of historian Robert A. Selig.

[26] Clermont-Crevecoeur, Jean Francois Louis, comte de. Journal of Jean Francois Louis comte de Clermont-Crevecoeur. In The American Campaigns of Rochambeau’s Army, translated and edited by Howard C. Rice and Anne S. K. Brown. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1972. vol. 1, p. 40. [27] Berthier. op. cit. p. 255. [28] Rochambeau, Jean Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur Comte de. “Correspondance du Comte de Rochambeau Depuis le Début de Son Commandement Aux États-Unis Jusqu’à la Fin de la Campagne de Virginie.” In Doniol Henri, Histoire de la Participation de la France à l’Établissement des Etats-Unis d’Amerique: Correspondance Diplomatique et Documents. Imprimerie Nationale/France, 1886. Vol. 5, pp. 475-476, 493-494, 510, 520-522, 524, 526. Rochambeau, Donatien Marie Joseph de Vimeur. “The War in America: An Unpublished Journal (1780-1783) by the Vicomte de Rochambeau.” In Weelen, Jean Edmond, and Donatien Marie Joseph de Vimeur Rochambeau. Rochambeau, Father and Son: A Life of the Maréchal De Rochambeau. Translated by Lawrence Lee, H. Holt, 1936, p. 224. Lauberdière. Op. Cit. pp. 124-125. [29] Verger. Op. Cit. pp. 134-135. Relation, ou Journal des Operations du Corps Français Depuis le 15 d’août 1781. Philadelphia: Hampton, [1781]. Doniol Henri. Op. Cit. vol. 5, p. 575. [30] Villebresme, Vicomte Maurice de. Souvenirs du Chevalier de Villebresme . . . Carnet de la sabretache: revue d’histoire militaire rétrospective. Volume: 4 (1896), pp. 177-194, 256-264, 313-325, 395-400, 422-438, 543-549. Also published in Paris, Nancy: Berger-Levrault, 1897. [31] Saint-Exupéry, Georges Alexander Cesar de. The War Diary of Georges Alexander Cesar de Saint-Exupery. Countess Anais de Saint-Exupéry. Légion d’honneur: honneur et patrie. American Society of the French Legion of Honor. Vol II, #2 (Oct. 1931), pp. 107-108. [32] Journal d’un officier du Regiment de la Sarre-Infanterie pendant la guerre d’amerique (1780-1782). S. Churchill. Carnet de la Sabretache: Revue d’Histoire Militaire Rétrospective. 2nd ser. Vol. III (1904), pp. 370-371. [33] Cromot Du Bourg, Marie François Joseph Maxime, Comte de. “Diary of a French Officer, 1781.” The Magazine of American History with notes and queries. New York: A.S. Barnes, 1877, (1893), p. 4, (1880), pp. 205-214, 293-308, 376-385, 441-452; 7 (1881), pp. 283-295. [34] British naval tactics focused on the hulls and decks of enemy ships, reducing their foe’s firepower and weakening the crew for eventual boarding. French tactics aimed at destroying the enemy’s rigging and masts, turning that ship into a drifting hulk, thereby allowing the French to rake the decks and force it to surrender. [35] So called because Cape Charles is on the northern entrance and Cape Henry is on the southern entrance to the Chesapeake Bay.