Virtually every major city throughout the United States and perhaps even the world celebrates the lives of prominent citizens and the aftermath of extraordinary events through the placement and dedication of statues, sculptures, monuments and memorials. The State of Rhode Island is no exception and City of Providence has more examples of these magnificent illustrations of public art than any other in the state with well over one hundred specimens. Some, such as the statue of President Abraham Lincoln in Roger Williams Park and the Memorial to World War II in War Veterans Park, represent people and events that are very familiar to almost everyone. Others, such as the statues dedicated to the memory of Sri Chinmoy and Constance Witherby, are examples that, to most, are nothing more than ghostly remnants of the lives and work of people who remain largely unknown.

In 2015 my daughter, Heather Caranci, and I set out to document each of the (at the time) ninety-five examples of public art and bring their stories to life through a series of short essays describing each work in an attempt to help explain their significance. The effort resulted in a 340-page book entitled Monumental Providence: Legends of History in Sculpture, Statuary, Monuments and Memorials. One of them is the story of Ebenezer Knight Dexter.

Most Providence residents are familiar with Dexter Street and the magnificent and imposing 1907 armory with its distinctive yellow bricks, crenellated turrets and decorative stonework that occupies the Dexter Training Grounds. The life of the person for whom the street and grounds are named, however, remains shrouded in secrecy to most. The story of the extraordinary societal contributions of Ebenezer Knight Dexter, whose statue is prominently placed on some of the land he so generously donated to the Town of Providence, is just one of many recounted in Monumental Providence that merits retelling.

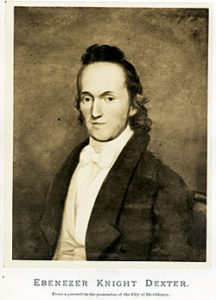

A descendant in the sixth generation of Roger Williams’ dear and faithful friend, Gregory Dexter, Ebenezer Knight Dexter was born on April 26, 1773, a year before disgruntled Rhode Island colonists burned the HMS Gaspee and more than three years before the signing of the Declaration of Independence. He was the youngest of seven children born to Knight Dexter and Phebe Harris Dexter. Despite the many births, only four of the children lived beyond their first year and, of those, all but Ebenezer died in their twenties.

Ebenezer Knight Dexter was just nine when peace was declared following the Revolutionary War. Though too young to fully grasp the significance of what he had seen and heard during those tense and bloody years, he was surely old enough to “catch the spirit of his elders and their spirited devotion” prompted by the horrors of those wartime events. Both the spirit and devotion apparently had a profound influence on his life.

After apparently enjoying a sound education, subsequent to the adoption of the U.S. Constitution in 1789, he embarked on a career in the mercantile trade and benefited from the “rising tide of prosperous trade and commerce” that followed it. He was a member of Providence’s quasi-aristocracy, counting among his closest friends people such as the Browns, the Fenners and respected U.S. Senator and Judge David Howell. Perhaps his success was buoyed by his 1810 appointment as United States Marshall for the District of Rhode Island, where part of his duties included handling the sales of ships seized in Providence harbor for nonpayment of debts.

Dexter also bought and sold real estate, accumulating hundreds of acres of choice land during his short lifetime. He approached his business ventures with such devotion that he was able to retire with a fortune at an age when most men were just starting to think about accumulating one.

Though financially sound and well respected, his life was full of the same difficulties that many others were forced to endure. Having already suffered the loss of his only child, Mary, just five months and ten days after her birth, Dexter suffered another heavy affliction from the death of his only true love, his wife Waitstill, in 1819, a loss from which he never truly recovered.

Upon his own death on August 10, 1824, Ebenezer Knight Dexter was laid to rest in the North Burial Ground, his grave marked by a magnificent obelisk. In reference to his passing, The Providence Gazette wrote, “in all the relations in his life he was a man of exemplary morals. As a son, brother, and a husband, dutiful, affectionate and liberal; prompt and conscientious in the discharge of his official duties, scrupulous and just in his dealings, and attached by principle to the institutions and liberties of his country, his death is a subject of regret to a numerous circle of relatives and friends, to his neighbors and fellow citizens and to the public institutions of which he was an active and efficient member . . . .”

Despite amassing considerable personal wealth, Dexter never lost sight of the plight of those less fortunate and held a deep compassion for the poor. He served on the town committee for poor relief, “but,” former City Archivist Paul Campbell wrote, “the extent of his beneficence to the less fortunate became evident following his passing.”

The reading of his will, according to Retired Chief Justice Thomas Durfee, “exhibited him [Dexter] in a new, and, in some respects, nobler aspect, as a munificent public benefactor.”

The most significant of his bequests in his lengthy will is found in a paragraph that reads in part, “Feeling a strong attachment to my native town, and an ardent desire to ameliorate the condition of the poor and to contribute to their comfort and relief, I give, grant and devise to the aforesaid Town of Providence . . . my Neck Farm . . lying southerly of the Friends’ Yearly Meeting School estate [now Moses Brown School], together with all the buildings thereon, to be appropriated to the accommodation and support of the poor . . . .”

As a condition to the bequest, Dexter’s will specified that the Town of Providence had to construct an almshouse on that land within five years and left a sum of money for that purpose. Three years later, the Dexter Asylum opened its doors on the site. Originally designed as a three-story structure, it was later enlarged with a mansard roof and dormers to better support the needs of the poor.

The will also stipulated very specific details about a stonewall that Dexter insisted surround the entire property. Despite the specificity of instruction on the construction of the wall, there was a significant lack of clarity for its purpose—it was not clear whether the wall was intended to prevent asylum residents from leaving or to prevent the public from entering. Regardless of its unspecified intent, the will required construction of a “permanent stone wall at least three feet thick at the bottom and at least eight feet high and to be placed on a foundation of small stones as thick as the bottom wall and sunk two feet into the ground.” When completed, the wall was more than a mile long, consumed over 1 million cubic feet of stone that was delivered to the site by oxcart, and took eight years to complete. Even if it was not on the scale of Hadrian’s Wall built in Roman times in Scotland, this was an impressive works project indeed. Much of the wall remains today and runs along Hope, Angell, Lloyd and Arlington Streets of the City’s East Side.

Initially the unemployed poor, among them malnourished immigrants (mostly Irish) who inhabited the facility, were “indentured” for a period of six months and were required to work on a nearby vegetable farm or at the asylum’s dairy. During these years the asylum was self-sufficient and for a time even profitable.

Eventually, due in part to the influx of destitute Irish immigrants into Rhode Island, the demands on the asylum began to grow and the Providence Town Council was forced to institute a cap of 180 residents. The cap, along with the growing indignation of those living in the fashionable East Side that developed around the asylum, caused its influence to begin to shrink. The neighbors objected to the smell of manure that often wafted into the kitchens and bedrooms of the nearby homes. The Dexter Asylum served the poor of Providence from 1827 until 1957 when the land was purchased at public auction by Brown University with a winning bid of $1,000,777.

Ebenezer Knight Dexter’s bequest of land and the asylum built on it served the needs of the indigent population of Providence for 130 years. It continues to benefit the poor of the city even today with funding from a foundation that was established from the proceeds of the sale of the Dexter Asylum to Brown University.

In addition to the those forty acres of land on the East Side, Dexter left a ten-acre tract of land to the Town of Providence on the West Side. The Dexter Training Ground was first used as a military training field, but in 1907 the Cranston Street Armory was built on a portion of the site. The balance of the land was eventually dedicated for use as a public park.

On June 29, 1894, a group of local dignitaries gathered at the training grounds for the dedication of a fitting memorial to the man who gave so much of himself to Providence and the poor who lived there. Acting Providence Mayor Daniel R. Ballou told those gathered that “In the swirling, swiftly flowing current of our complex civilization, men are inclined to neglect, if not to disregard the lessons which have been drawn from the experiences of human kind. It is profitable, therefore, to pause now and then, amid the engrossing activities of a busy life, and take a retrospective view of past events, that our minds may be so enlightened thereby that our future action shall be guided by wisdom and prudence.” With those words, spoken 122 years ago, Mayor Ballou, unveiled a statue commemorating the life, generosity and philanthropy of Ebenezer Knight Dexter.

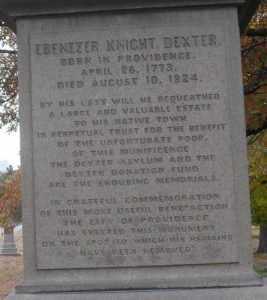

The handsome bronze figure, located in the heart of the Dexter Training Grounds, is eight feet tall and stands upon a magnificent granite plinth that is nine feet high. Mr. Dexter is represented in continental costume; in his left hand is a walking stick and in his right, a partially opened scroll of parchment. The inscription on the pedestal, which was designed by Parks Commissioner R. H. Deming, reads, “Presented to the citizens of Providence by Henry C. Clark, Esq., in honor of Ebenezer Knight Dexter, who gave his property for the benefit of the public and the homeless, 1893.” The other side of the pedestal is inscribed, “Leaving nothing but a headstone to mark our passage through life does not make the world better. They live best who serve humanity the most.”

By all accounts of those present at the dedication, a contingent that numbered nearly 1,000 dignitaries, citizens and students standing beneath the low grey clouds responsible for the steady drizzle that fell upon them, these words epitomized the life of Ebenezer Knight Dexter. Unlike Abraham Lincoln, Oliver Hazard Perry, Nathaniel Greene, Esek Hopkins and so many others so honored with statues in Providence, hardly a person today knows who Dexter was or why his life warranted such warm remembrance. Hopefully, this article will help to rectify that shortcoming.

Dexter was inducted into the Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame in 2000 in the hope that his contributions to the people of Providence and his example to all Rhode Islanders will never be forgotten. Perhaps the next time you pass by the magnificent work of public art dedicated to the life of a philanthropist and public benefactor you will pause to take a good look at the man who in both life and death dedicated his time and resources to the improvement of the human condition.

[Banner Image: Statue of Ebenezer Knight Dexter on the Dexter Training Grounds, Providence]Further Reading:

Rhode Island Historical Society Library, Manuscript Division, Dexter Asylum Records. (The first three volumes are of particular interest.)

John Smith, “Mr. Dexter and his Farm,” Brown Alumni Monthly (1963), 17.

- C. Newman, Dexter genealogy: being a record of the families descending from Rev. Gregory Dexter (Providence: A.C. Greene, 1859).

Report of the Exercises at the Dedication of the Statue of Ebenezer Knight Dexter Presented to the City by Henry (Dedicatory Exercises of the Statue of Ebenezer Knight Dexter. (Approved December 4, 1894. Resolved, That the joint special committee appointed by resolution No. 401, series of 1893, and Nos. 21 and 384, series of 1894, be and said committee is hereby authorized and directed to have printed for the use of the City Council five hundred copies of the report of the dedicatory exercises of the statue of Ebenezer Knight Dexter on June 29, 1894).

Paul Caranci and Heather Caranci, Monumental Providence: Legends of History in Sculpture, Statuary, Monuments and Memorials (Chepachet, RI: Stillwater River Publications, 2015).