Passengers and carmen enjoyed a close, personal rapport during the horsecar period. Despite a company prohibition against “unnecessary conversation with passengers,” both drivers and conductors cultivated a clientele almost like seasoned salesmen. When John Potter ended a forty-one-year career as conductor in 1911, a newspaper article described a vanishing way of life in industrialized Rhode Island, “When patrons on the few lines that radiated out from Market Square felt a personal interest in the men who drove the horses and collected the fares, and when each conductor had his own particular following.” Lyman Eager spent a lifetime in transportation driving a stagecoach, horsecar, fire engine and, finally, Union Railroad trolley. When he lived In the neighboring Bay State in the 1860s, “persons from all over the eastern portion of Massachusetts went out for the sole purpose of riding with him” on the stagecoach. William Vinton recounted three decades of toil as a conductor: “I knew intimately all the regular passengers who travelled with me every day. I never had to ask the people who travelled with me where to stop, for I knew their streets as an elevator boy knows the floors for the regular occupants of a business building. Even now when I have a car full of ‘regulars’ I don’t call the streets, but if there are any strangers on board I do.”

Many employees spent a lifetime on the same route, sometimes evolving along with transit technology. Eugene Tompkins’ obituary mentioned, “During the nearly two score years that he was in the active employ of the Rhode Island Company (successor to the Union Railroad), Mr. Tompkins ran cars almost entirely on the so-called Elmwood Avenue lines, and thus became well known and liked by the hundreds of the company’s patrons between the Elmwood barn, Butler Avenue on the East Side, and along Smith Street, as his schedule sometimes directed him.” One enterprising conductor, a stickler for mathematical figures like many of his co-workers, kept a personal record of passengers he served

between 1870 and 1888. He collected 2,181,487 fares, took in almost $110,000 in cash and over $1,000,000 in nickel tickets, and traveled over 340,000 miles.

Drivers and conductors performed innumerable courtesies for passengers above and beyond the call of duty. Daily intercourse mandated respect and gentility unexperienced in most other walks of life, even in the transportation and service industries. John Wall encapsulated that philosophy when he talked about his life as a conductor on the rails. “The passengers were very friendly with the drivers and conductors, and many times if the regular riders were late for their cars, they would whistle for us to stop, and we would wait for them to come out. In all the thirty-eight years I have worked for the company, I have found that if the conductor was gentlemanly and courteous to the public, that the public would be equally so to them. The regular riders always had a friendly greeting for the drivers and conductor when they entered the car, this we appreciated, and it made the day’s work pleasanter for both.” Daniel Vickerie, another veteran of stagecoach, omnibus, horsecar and trolley service, practiced civility as a driver. He learned “to always turn out when he met another vehicle and give the other vehicle the right of, way and he would never have any trouble.”

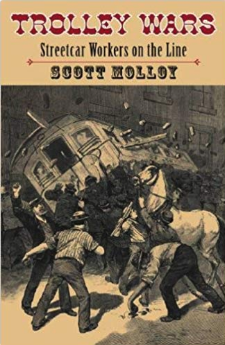

Two street car conductors standing at the front of a horse-drawn trolley. One is holding the reins to the two horses that pull the trolley, and both men are holding a bouquet of flowers. Other trolleys in a garage are seen in the background (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

The employees did other favors that reinforced camaraderie. Conductors frequently turned in lost pocketbooks and wallets, sometimes, containing significant amounts of money. Many sold individual tickets for five cents instead of blocks of twenty for a dollar, as required by the company, thus saving the customer a cent on each ticket. The . Union Railroad enforced a rule to charge passengers a double fare for bringing large packages and loads onto the horsecar, the conductors by implication not wishing too overburden patrons with an extra charge of 47 cents. The crew frequently delivered parcels and newspapers “all along the line” as a favor to passengers and businessmen. Drivers and conductors, many of whom lived in the same neighborhoods as their passengers, served as information bureaus to the general public.

These kindnesses, sometimes contrary to company policy, protected carmen from private grievances or public ridicule. “Few complaints are made to the company against the men for incivility,” noted the Providence Journal,” and as the public well knows on all of the routes in the city, the conductors and drivers are as a rule very gentlemanly in their treatment of passengers. They are an exceptionally intelligent class of men.” A person nominated for constable in Providence was turned down by the city council when “it was stated that a man by that name had insulted the conductor of a horse-car, and it was voted that no more constables be added. “The Morning Star complimented the operation too: “The cleanliness of the vehicles, the good character of the horses, the intelligence, gentlemanly deportment and accommodating spirit of conductors and drivers, all make traveling from one part of the city to another and to the suburbs as pleasant as a vacation excursion.” A summary characterization appeared in 1886: “What a car conductor don’t know about every regular patron of the line isn’t worth knowing.”

A horse-drawn trolley traverses Broad Street in Providence, 1872 (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

Passengers displayed their friendship and appreciation in many ways. Drivers and conductors received turkeys, candy and other gifts for Christmas. Residents along Broadway in Providence brought hot meals to crews who worked winter holidays. A retired old timer recalled, “Just about this time of year, the old horsecar drivers were particularly accommodating, for more than one turkey or chicken found its way to their homes, the gifts of patrons, along their way.” A greenhouse proprietor in the Edgewood section of Cranston gave flowers to Broad Street carmen on Easter. Other patrons dispensed lemonade on the Fourth of July in Pawtucket, and a Prairie Avenue resident supplied coffee and doughnuts on a cold February in 1886.

Not all carmen were so revered. Some “knocked down” fares for themselves. Incidental arguments sometimes .erupted between passengers and crews. Rookie drivers and conductors tried the patience of patrons and co-workers alike. “A good many people when they want to stop a horsecar sing out “hay” to the conductor, “observed The Morning Star in 1886. “Grass” would be more appropriate to yell at the green conductor who persistently keeps his back turned on running, screaming passengers.” The city of Pawtucket employed small “bobtail” horsecars with only one attendant who doubled as driver and conductor. According to an irate patron of the line, it took “a public gymnastic performance to attract the attention of the driver.” However, the superintendent of operations claimed that “the men are honest, capable and faithful. There is not so good a set of men upon the horsecars in any other city in the country.”

The conductors and drivers also promoted a sense of brotherhood within their own ranks. As a group, they were outdoorsmen, uncomfortable in the confines of a factory or mill. “The man who has had his car seldom goes back to work in the shop.” One youngster, fresh from the wilds of Maine in 1890, became an apprentice in an Olneyville mill: “Bill made a try at it but, after his life in the open, being shut up in a mill did not appeal to him and he proceeded to get a job as conductor on the horsecars.” Farm work and horse experience developed an urban wanderlust, a need to keep moving, if only along a familiar repetitious route. The job practically required such a personality. As late as 1909; a study of Providence’s labor force concluded: “The street-car employees are mostly Americans (native born), some of whom have come from the rural districts or from the mills and factories, and others from clerical positions to get the benefit of work in the open air.”

A horse-drawn trolley on Weybosset Street in Providence (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

Horse carmen worked together and socialized whenever time permitted. They chatted, philosophized, and argued during many split shifts, spending much time at various carbarns bantering with one another. They went on sleighing parties, practiced polo and baseball, and played practical jokes. “Pop” Spear, a venerable horsecar driver, bet the crew of two other cars in front of him he could reach the carbarn before they could. The others quickly accepted the absurd proposition, figuring there was no way the old-timer could, pass them without their consent. He gave them a head start, then took a shortcut by driving his horsecar right off the rails and down a trackless side street. When his rivals arrived at the barn, they found him unconcernedly smoking his pipe. Employees also presented gifts for grooms and retirees, occasionally serenaded co-workers, and made collections for the sick and injured. Conductors and drivers wore black mourning, ribbons on the job when a compatriot died, as a show of respect and affection.

[Banner image: Two street car conductors standing at the front of a horse-drawn trolley. One is holding the reins to the two horses that pull the trolley, and both men are holding a bouquet of flowers. Other trolleys in a garage are seen in the background (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)]