Woonsocket’s famed politician, Lieutenant Governor and Mayor Felix A. Toupin, and West Warwick’s prominent Judge Alberic Archambault, were primarily responsible for the transition of the Franco-American vote in Rhode Island during the 1920s and early 1930s from the Republican Party to the Democratic Party. They were to be posthumously inducted into the Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame during a ceremony at the West Warwick Country Club on Sunday, March 8. But then the coronavirus crisis got in the way. Still, we can celebrate the many and varied accomplishments of Toupin and Archambault in print.

In addition, the new book “Fighting Bob” Quinn: Political Reformer and the People’s Advocate, edited by Russell DeSimone, and recently published by the Rhode Island Publications Society, containing the political recollections of Governor and Judge Robert Emmett Quinn, was also to be released at the Hall of Fame induction ceremony. But the book can also be enjoyed in print (see the link to the book on the right side bar of this article.)

Quinn was a central figure in Rhode Island’s turbulent transformation in the 1920s and early 1930s from a Republican-dominated state, which it had been since the 1850s, to one that is still dominated by the Democratic Party. Consistent with his “Fighting Bob” nickname, Quinn challenged powerful politicians, was relentless in the pursuit of his goals, and never backed down. This book is a celebration of his fighting spirit.

As President of the Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame’s Board of Directors and Rhode Island Historian Laureate, I am proud to provide the following summaries of the lives of this year’s two Hall of Fame inductees.

Judge Alberic A. Archambault

Alberic Archambault was born in St. Cesaire, Province of Quebec, Canada on February 9, 1888, one of 14 children of Lucien Archambault (1850-1922) and Marie Anne Gareau (1851-1940). The family emigrated to the United States in 1889 and settled in the West Warwick village of Natick.

Archambault obtained his early education at St. John the Baptist School in the village of Arctic, then went on to LaSalle Academy, St. Hyacinthe College, P.Q. Canada, and graduated from the Boston University School of Law in 1908. That same year he was admitted to the Rhode Island Bar.

Three years later, on August 11, 1911, Alberic married Louise A. Dion (1892-1967). From 1913 to 1927 seven children were born to the couple: Justa, Cecile, Françoise, Dion, Raymond, Gerald, and Aline. The family lived in a spacious home at 1384 Main Street, West Warwick.

Even with a family and law practices in Providence, West Warwick and Woonsocket, Alberic found time to immerse himself in politics, real estate, and writing.

He began his political career in 1912 serving as city solicitor in Warwick. He was one of the key figures in the division of Warwick, a 1913 partition orchestrated by Patrick Henry Quinn, that separated the mill villages of Warwick’s western side from the more agricultural eastern section. After the partition, Alberic became West Warwick’s first senator. Then, in 1918, he was the unsuccessful Democratic candidate for governor, but as a reward for his effort, he was made chairman of the Democratic State Committee. Archambault served again as West Warwick’s senator from 1925 to 1929 and in 1928 made another unsuccessful run for governor, losing by a narrow margin. In 1935 Governor Theodore Francis Green appointed him to an associate judgeship on the state Superior Court, a position he held with distinction until his death in 1950.

What is not immediately evident in this mere listing of Archambault’s political positions is the fact that he was the first Franco-American Democratic candidate for governor (1918), a run he unsuccessfully repeated in 1928; he was the first of his ethnic group to serve as Democratic state party chairman; he was a principal ally of Felix Toupin, Patrick Henry Quinn, and Robert Emmet Quinn in attempting to reform the state’s constitutional system; and, especially, he was the leader, with Toupin, in attracting the Franco-American vote to the Democratic Party. These long-forgotten exploits during the 1920s, earned him that Superior Court judgeship on January 10, 1935, in the immediate aftermath of the famous Bloodless Revolution.

Archambault was also a major real estate developer. In 1925, when Route 3 was constructed, the new highway spurred development, especially on the shore of Lake Tiogue in Coventry. Archambault saw an opportunity to establish a summer colony around the lake. He bought all the land from the beach near the former Tiogue Vista (built in 1929) to the causeway of Twin Lakes on Arnold Road. There he developed the Tiogue Pine Beach and Tiogue Twin Lakes plats.

In the late 1920s, he conceived the idea of building a lakeside restaurant in a structure resembling an ocean liner with a bow and stern and a cocktail deck at the second story level. The initial location of the “Showboat” was on Arnold Road along the westerly shore of Lake Tiogue. In 1937 it was moved across the lake to a site on Route 3. Alberic owned the Showboat until the 1930s when it was sold to Alphé (Kid) Blier (aka Blair) who added a long shoreside dining room. Kid Blair operated the Showboat as a restaurant and banquet facility until it was engulfed by fire on January 16, 1976.

During World War II, Archambault purchased a large tract of land in the Quidnick section of Coventry. He divided it into house lots, designated the plat Truman Heights, and named the streets after his children.

The versatile Archambault wrote two books. The Samsons, published in 1941, revealed his concern with the impending war in Europe that led to the Holocaust and Jewish persecution. In it he expressed his views about the political, social, and economic undercurrents in the country at that time. His second book, Mill Village, published in 1943, is a historical novel about the French-Canadians who emigrated to the United States to work in the textile mills of southern New England. In this volume he relays much of his own experiences as a youth.

Judge Archambault passed away on November 26, 1950 at the age of 63. At his funeral a large gathering of family and friends, together with church, state, and local dignitaries, assembled at St. John the Baptist Church in Arctic to pay tribute to a man who had accomplished so much in his life. At his passing the Providence Journal stated that: “He was Rhode Island’s most colorful and outspoken judge during his years in court.” He and Louise are buried in St. Joseph’s Cemetery, West Warwick.

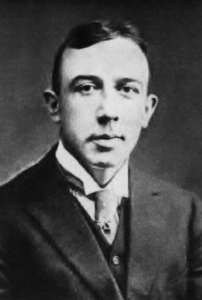

Lt. Governor and Mayor Felix A. Toupin

Felix A. Toupin was born on August 31, 1886 in the Lincoln mill village of Manville to French Canadian immigrants Dieudonne and Mary (Proulx) Toupin. His intelligence prompted his parents to sacrifice in order to provide him with a good education at LaSalle Academy and Joliette Seminary in Quebec. In 1913 he graduated from Boston University School of Law.

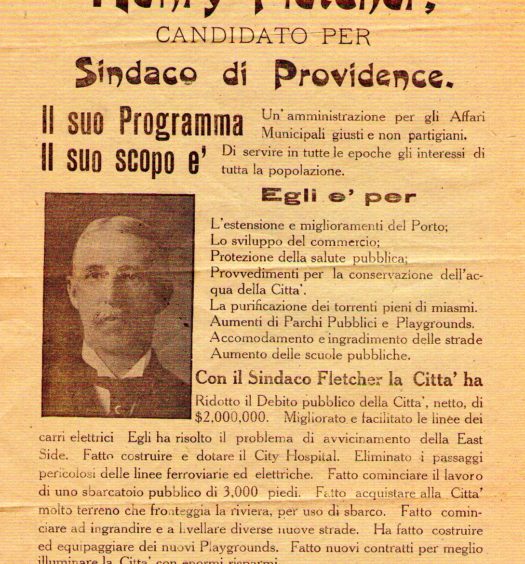

After service in World War I, Toupin began to practice law in Lincoln and Woonsocket, engage in real estate development, and become involved in politics. In 1920 he was elected Democratic state representative from Lincoln. Quickly, his oratory, assertiveness, and proud Franco-American heritage won him the party’s nomination as lieutenant governor in 1922 after several Republican political blunders weakened the GOP’s hold on the French vote. During that campaign he toured the French neighborhoods and mill villages denouncing the bill sponsored by Republican state chairman Frederick Peck that mandated the use of English in school instruction—even in Franco-American parochial schools.

After winning the election, Toupin, his running mate, governor William Flynn of South Providence, and Senator Robert Emmet Quinn of West Warwick attempted to implement a reform agenda, especially the call of a constitutional convention to broaden the suffrage and equalize representation in the state senate.

The 1922 electoral landslide gave Democrats control of the House but the malapportioned, rural-based Senate remained narrowly in Republican hands. However, Toupin, as lieutenant governor, was the Senate’s presiding officer. In 1924 after many legislative deadlocks and filibusters, a House-passed bill authorizing a constitutional convention was taken up by the Senate.

The Democratic minority, led by Quinn and Toupin, staged a marathon filibuster to force weary Republicans to pass the constitutional convention bill. The strategy of Toupin was to wear some of the elderly Republicans down and then call for a vote on the question when they snoozed or strayed.

In the 42nd hour of the filibuster, as the vigilant Democrats awaited the success of this scheme, Republican party managers authorized some thugs imported from Boston to detonate a bromine gas bomb under Toupin’s rostrum. As the fiery Woonsocket politician keeled over unconscious, senators scrambled for the doors. Within hours most of the Republican majority was transported across the state line into Massachusetts, where Toupin’s summons could not reach them. There they stayed (Sundays excepted) until a new Republican administration assumed office in January 1925.

Ironically, the defeat of the Democrats in the 1924 state elections was due in part to the fact that the Providence Journal wrongly accused them of the bombing. The newspaper had particular reason to discredit the Democrats that year, inasmuch as Jesse H. Metcalf, brother of the Journal’s president, was the GOP candidate for the U.S. Senate in the fall election against incumbent governor William S. Flynn. The paper’s strategy worked.

To stem the defection of Franco-Americans from the Republican Party, popular ex-governor Aram Pothier was summoned from retirement to battle Felix Toupin in the 1924 governor’s race. With the Democrats unjustly blamed for the stink-bomb incident, Pothier and the GOP won a decisive victory in this unprecedented battle between Franco-American leaders, but Toupin outpolled Pothier in Woonsocket by 1,100 votes!

In 1930 Toupin withdrew from the state’s political wars and moved from Manville to run for mayor of Woonsocket. He beat his Republican opponent by more than a two-to-one margin. As the city’s chief executive he governed the city in a fiscally responsible manner during the Great Depression, although he was often at odds with the city council and other departments of city government. His policies reflected the philosophy of Woonsocket’s business community regarding economy in government. He was frugal and efficient as chief executive.

Despite labor unrest Toupin easily won reelection in 1932 and again in 1934 as Democrats swept all offices. However, when Toupin was unfairly by-passed by the state Democratic Party in the aftermath of the Bloodless Revolution of 1935, the mercurial and feisty Toupin left the party and, amazingly, ran for a fourth term as a Republican. He was defeated by Democrat Joseph Pratt—10,584 votes to 7,310. Undaunted, Toupin made a comeback in 1938 when the state Democratic Party suffered the effects of a national recession and the infamous Race Track War. In 1940 a strong Democratic revival ousted Mayor Toupin for good. He became the man without a party, although he continued to speak out on local issues.

In 1955, Felix came out of retirement to challenge the very popular Democratic mayor Kevin K. Coleman, a Hall of Fame inductee. The incumbent Coleman, who easily won election in 1953 with 68% of the vote, barely edged Toupin who made an earnest plea for the support of the city’s dominant Franco-American community. The veteran campaigner lost by only 795 votes of the 20,165 cast.

A man of boundless energy and daring, Toupin was one of the most dynamic Rhode Island politicians of the 20th century. Like Alberic Archambault, his greatest significance was the leadership role he played in attracting Rhode Island’s Franco-American voters to the Democratic Party, but a reward for that political feat escaped him while the other four main transitional politicians all gained judgeships.

Toupin’s first wife Delia Chapon died in 1962; he then married Blanche Lavimodiere the following year. When Toupin died on October 7, 1965 at the age of 79, Blanche survived him. He is buried in St. James Cemetery in Lincoln.

[Banner image: Woonsocket Falls and the Sayles Street Bridge in Woonsocket, circa 1910 (Providence Public Library Digital Collections]