The popularity of spies in the Revolutionary War, led by AMC’s TURN cable television series and the bestselling book George Washington’s Secret Six: The Spy Ring that Saved the American Revolution, the impact that spies had on the outcome of campaigns and other aspects of the war has sometimes been exaggerated. I focus on two examples in my book, Spies in Revolutionary Rhode Island. The first example deals with the Culper Spy Ring and was the subject of an earlier article. This article deals with the second example, the British spy Ann Bates.

One of the few known female spies on either side in the Revolutionary War, Ann Bates spied for the British during the Rhode Island Campaign of July and August 1778, the first time the French and American forces jointly cooperated to attack a British outpost. The joint expedition failed to capture the British garrison defending Newport, but the American army fought well at the Battle of Rhode Island on August 28, 1778.[1] Bates provided her British handlers with valuable intelligence, despite never setting foot in Rhode Island. However, she did not, as some historians claim, play a crucial role in the British triumph.

Born around 1748, Bates worked as a schoolteacher in Philadelphia. Because her husband was a soldier and gun repairman in the British army, she learned about weaponry and the importance of military information, such as the enemy’s cannon, soldier and supply totals. At some point during the British occupation of Philadelphia, Ann Bates met with John Craig (sometimes Craiggie or Cregge), a civilian active in British General Sir Henry Clinton’s espionage network. Craig judged her, accurately, as it turned out, to be intelligent and resourceful—just the right type to thrive as a spy. Bates performed a few secret tasks for Craig.

The Bates family’s world changed dramatically when Clinton, the new commander in chief of British forces in North America, decided to evacuate Philadelphia in response to news of the alliance between France and America and the anticipated imminent arrival of a French fleet in Chesapeake Bay. After her husband joined Clinton’s army, which marched out of Philadelphia on June 18, 1778, bound for New York City, Ann followed. When, on about June 26, she arrived in the city serving as British headquarters, she asked to see Craig. Instead, she was taken to meet with one of Clinton’s spy handlers, Major Duncan Drummond. Drummond and Craig together persuaded Bates to spy for the British army. Drummond subsequently wrote: “a woman whom Craig has trusted often came to town last night. She is well acquainted with many of the R.A. [Royal Army]…It is proposed to send her out under the idea of selling little matters” in Washington’s camp and there “she will converse with Chambers and will return whenever she may have learnt anything that deserves to be known.”[2] Craig later received a nice finder’s fee from the British secret service for bringing Bates to Duncan’s attention.[3]

After a mere single day of training, on June 29, Ann departed New York City on her first mission. Using the cover name “Mrs. Barnes,” Bates disguised herself as a peddler. She was given five guineas for expenses to buy items for a peddler’s pack—thread, needles, combs, knives and some medicines. On July 2, she arrived at Washington’s camp at White Plains, New York. As “Mrs. Barnes,” she freely traveled amongst the American soldiers and camp followers. Drummond had instructed Bates to find a disloyal soldier, named Chambers, and to glean any useful intelligence from him. However, she could not find him. Bates then resourcefully changed her mission to find out what useful intelligence she could. She listened in on conversations, located gun emplacements and counted artillery pieces. After finally selling most of her merchandise, she made her way back to Drummond in New York City.

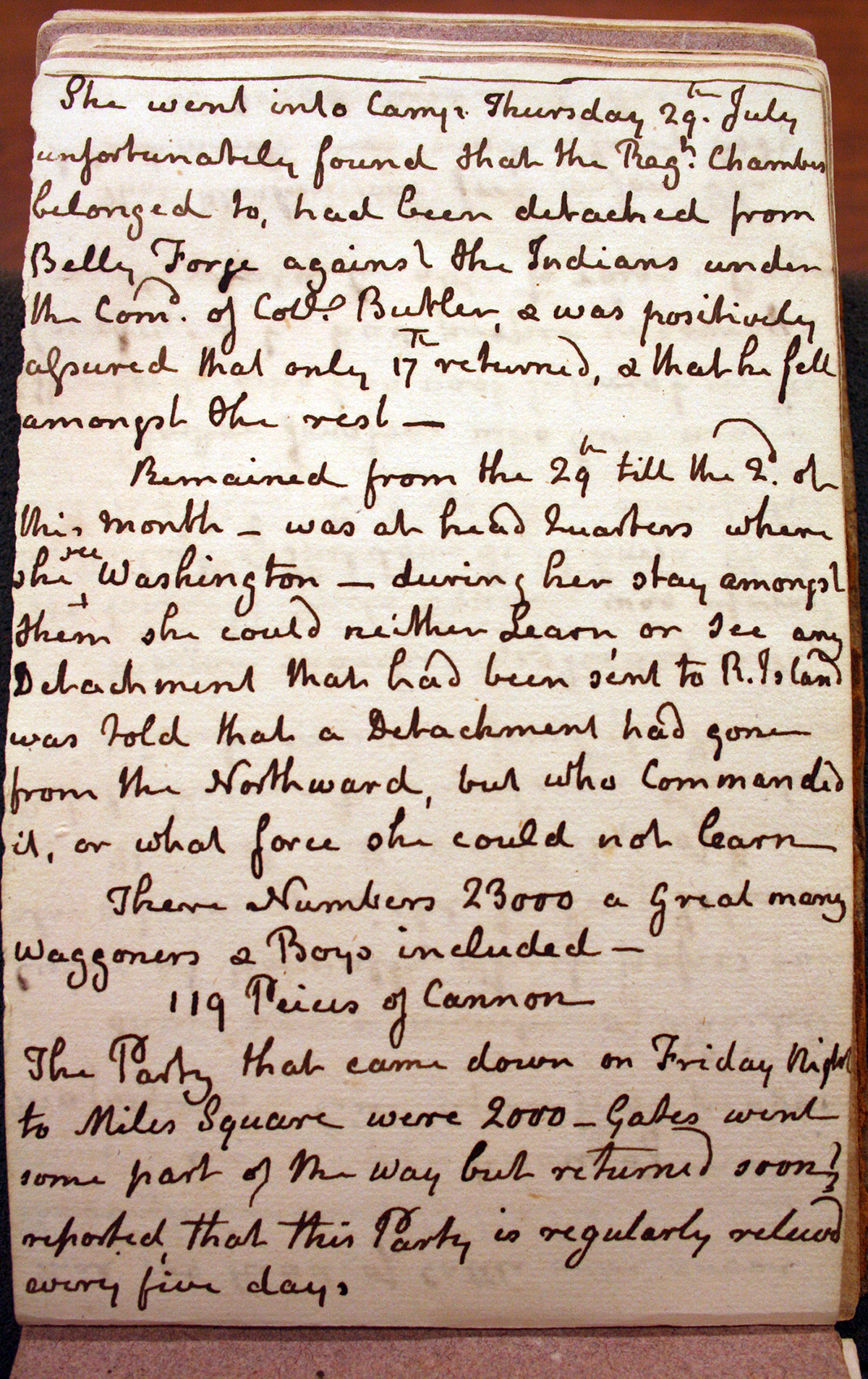

Bates began to spy on Washington’s army at a time when it was sending Continental regiments eastward to augment the American army in Rhode Island. On July 29, 1778, Major Drummond dispatched Bates back to White Plains. Still disguised as Mrs. Barnes, the peddler, she evaded or passed through multiple military checkpoints and finally arrived at Washington’s camp. She was again unable to locate Chambers, her contact. (She learned later that he had been killed in a battle in the Mohawk Valley.) Bates therefore spent the next three or four days wandering about the American camp, counting “119 pieces of cannon” and estimating the number of soldiers at 23,000. She spotted ten wagons rolling into camp “with wounded” in them. She also described the locations of the American brigades. She even boldly entered the residence temporarily being used as Washington’s headquarters and spotted the commanding general but did not learn any useful information there.[4] She was informed, however, that no American troops had yet been dispatched to Rhode Island. “During her stay amongst them,” wrote Drummond after Bates’s return to New York City on August 6, “she could neither learn nor see any detachment that had been sent to Rhode Island.”[5]

Just two days later, Bates was sent back to White Plains for a third time, arriving on August 12. At Washington’s headquarters she overheard an officer whom she thought was a general inform one of Washington’s aides-de-camp (perhaps Alexander Hamilton) that 600 boats were being prepared for an invasion of Long Island by 5,000 troops (this attempt was never made). She also learned that about 3,000 Continentals and 2,000 militiamen had left camp for Rhode Island. Bates observed that with the departure of another detachment of 3,800 “picked men” to Dobbs Ferry, the American camp “was not near so numerous as when she was first there, nor their parades half so full.” She estimated the strength of Washington’s army had fallen to 16,000 or 17,000 troops. She counted fifty-one pieces of artillery on Saturday and saw nine more cannon arrive in camp the next day.[6]

Bates took pride in her role, writing in a petition for a pension in 1785 that “my timely information was the blessed means of saving the Rhode Island garrison with all the troops and stores who must otherwise have fallen a prey to their enemies.” Duncan Drummond was asked to review Bates’s petition, and he observed that “she asserts nothing but what is strictly true” and that “her information…was by far superior to every other intelligence.”[7] Paul R. Misencik, who recently devoted a chapter in his book on spies to a detailed history of Ann Bates’s espionage activities, called her Britain’s “most effective” spy, in large part based on her supposed decisive role in the Rhode Island Campaign.[8]

Bates’s role in the Rhode Island Campaign has been exaggerated. Mostly importantly, the timing is off. Early in the morning of July 22, 1778, Continental brigades commanded by James Varnum of Rhode Island and John Glover of Massachusetts, totaling 2,500 soldiers, set out on their 160-mile trek to Rhode Island. Later that morning, Washington appointed Major General Marquis de Lafayette to command the detachment, forcing the young French aristocrat to gallop off to catch it.[9] Lafayette’s Continentals reached Tiverton, Rhode Island, the staging area for the invasion of Aquidneck Island, on August 8. Accordingly, when Bates reported to Drummond on August 6 that no American troops had yet left for Rhode Island, she was incorrect. In addition, on August 19, after her next trip to the White Plains camp, Bates told Drummond of the movements of the two Continental brigades. She added that 2,000 militiamen accompanied this detachment, but this too was untrue.

When Bates returned to Clinton’s headquarters on August 19 and belatedly warned of American troop movements to Rhode Island, it is said that this information led Clinton to reinforce the Newport garrison, which helped to defeat the combined French and American forces outside Newport.[10] However, this could not be accurate, as Clinton never sent any reinforcements to Newport in August because the French fleet had arrived outside Narragansett Bay on July 29. Back on July 9, concerned that Newport would be exposed to an attack by the French fleet when it arrived, Clinton had prudently sent 1,850 troops under Major General Richard Prescott, by boat through Long Island Sound to reinforce the Newport garrison.[11] However, this was weeks prior to Lafayette’s Continentals departing White Plains for Rhode Island on July 22.

Excerpt from Major Duncan Drummond’s Memorandum Book, reporting about Ann Bates (Library of Congress)

Still, Ann Bates was a remarkable woman and a valuable spy. Her ability to manage the physically grueling trips between her posts without resting long and getting past the many Continental army checkpoints was impressive. Bates’s efforts proved that women could be valuable spies. They were often able to overhear secret information because they were considered unable to understand the complexity of military affairs. The discriminatory attitude could make women even more effective as spies.

Disguised as a mere peddler, Bates was able to penetrate even Washington’s headquarters. Bates was paid for each of the three trips she made to Washington’s camp—twenty dollars, thirty-one dollars and thirty dollars.[12]

The British spy Ann Bates continued to perform clandestine missions between 1778 and 1780. In September 1778, when she was on another mission infiltrating Washington’s army, a deserter from the British Twenty-Seventh Regiment recognized her, but she was able to elude capture.[13] This event, however, led Ann to cease penetrating Washington’s headquarters. Later, Ann was sent to escort from Philadelphia to New York City a female secret agent who had helped to turn Benedict Arnold. A series of safe houses provided shelter for the female spies until they came to the New Jersey shore of the Hudson River. To avoid both a storm and detection by Patriot scouts, the women had to stay hidden in a Loyalist’s cellar for three days. Bates also provided her superiors with a report on Philadelphia shipping and the amount of flour to be found in its “rebel” mills.

When her husband was sent to Charleston following the British capture of the city in May 1780, Ann Bates travelled with the troops to South Carolina but did not engage in any further espionage activities. The couple sailed to England in 1781. Later deserted by her husband and in dire financial straits, she successfully petitioned the British government for a small pension because of her wartime spying.[14]

* * *

Most of this article is from Christian McBurney, Spies in Revolutionary Rhode Island (History Press, 2014). This article originally appeared in the Journal of the American Revolution at www.allthingsliberty.com.

Notes

[1] See Christian McBurney, The Rhode Island Campaign: The First French and American Operation of the Revolutionary War (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2011), passim. [2] Undated note, probably by Major Duncan Drummond on June 28, 1778, Henry Clinton Papers 234:27, William L. Clements Library. This note has the same handwriting as in the British Intelligence Memorandum Book noted in the note below. [3] Undated entry (near end of book), British Intelligence Memorandum Book, MMC-2248, Manuscript Reading Room, Library of Congress. [4] The information on Ann Bates, unless otherwise stated, is from British Intelligence Memorandum Book, July 21-November 10, 1778, MMC-2248, Library of Congress, and Petition of Ann Bates, March 17, 1785, British Treasury Papers, In-Letters, T1/611, British National Archives. Bakeless also relied on these sources, and Misencik relied primarily on Bakeless. See John Bakeless, Turncoats, Traitors and Heroes (New York, NY: Da Capo Press, 1975), 252-58 and Paul Misencik, The Original American Spies: Seven Covert Agents of the Revolutionary War (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2014), 78-86. To the author’s knowledge, Bates’s petition and the supporting documents are not held by any library or archives in the United States. While the identity of the author of the intelligence book is not certain, it probably was penned by Major Drummond. [5] Journal, August 6, 1778, British Intelligence Memorandum Book, MMC-2248, Library of Congress. [6] Ibid., August 19, 1778. [7] Ann Bates’s claim for compensation, March 17, 1785, British Treasury Papers, In-Letters, T1/611, British National Archives. [8] Misencik, Seven Covert Agents, 86. [9] McBurney, Rhode Island Campaign, 78. [10] Bakeless, Turncoats, Traitors and Heroes, 257; Misencik, Seven Covert Agents, 85. [11] McBurney, Rhode Island Campaign, 76. [12] Undated entry (near end of book), British Intelligence Memorandum Book, MMC-2248, Library of Congress. [13] Journal, undated (about September 30, 1778), British Intelligence Memorandum Book, MMC-2248, Library of Congress. See also Petition of Ann Bates, March 17, 1785, British Treasury Papers, In-Letters, T1/611, British National Archives (“an English deserter who knew me gave information who I was so that I was obliged to make a precipitate retreat for fear of being taken up as a spy”). [14] Bakeless, Turncoats, Traitors and Heroes, 258–62; Misencik, Seven Covert Agents, 86–91.