“The moment I heard of America, I lov’d her.” The Marquis de Lafayette wrote this in a letter from his camp near Warren, Rhode Island, on September 23, 1778. It was addressed to the President of Congress in response to a Resolution of Congress praising his efforts during the last stages of the Rhode Island Campaign. If Lafayette loved America, Americans have loved Lafayette.

Lafayette’s last visit to Rhode Island was part of a grand tour as a guest of the government of the United States. The Marquis de Lafayette arrived in Providence August 23, 1824. It was an opportunity to refresh connections to the Revolutionary War generation and to highlight the progress the country had made as an independent country grounded in democracy.

The 1824 visit to Rhode Island was one of four visits to the state made by Lafayette in his lifetime. His first visit to Rhode Island was during the perilous times of the Rhode Island Campaign in 1778. His second visit was in the summer of 1780. Washington sent Lafayette to carry his greetings to Rochambeau. Lafayette remained in Newport with Rochambeau at Vernon House (Rochambeau’s headquarters) until July 31, 1780. By August 7th Lafayette was back in Peekskill, New York, commanding his troops in the Continental Army. In 1784 Lafayette journeyed to Newport and then Providence where he was greeted with pomp and ceremony during a brief third visit to Rhode Island.

This article will summarize Lafayette’s four visits to Rhode Island, starting with his triumphant return in 1824.

Bicentennial celebrations of Lafayette’s grand tour in 1824 have recently been in the news and special events were held in the communities Lafayette visited. Back in 1824, organizing a tour of all the states in the United States took considerable effort. The Providence organizing committee was unsure which roads the Marquis would be taking to travel to Providence, so they posted messengers along various roads. Exactly how he traveled and where he stopped along the way varies in different accounts, but he probably spent the night before his visit to Rhode Island in Plainfield, Connecticut. A delegation from the Providence Town Council met him there and they left early in the morning riding down the Plainfield Pike. In the carriage with him was the now elderly Ephraim Bowen, one of his wartime companions. They stopped at Brown’s Tavern for breakfast. Lafayette was transferred to a luxurious, open barouche carriage drawn by four white horses. He traveled along a predetermined route and was, according to the Providence Gazette’s August 25, 1824, edition, “welcomed by that most expressive token of affection interest, the waving of white handkerchiefs by the fair hands of the ladies.”

There was a procession through High Street, down Westminister to Weybosset Bridge and up North Main Street and next to the State House (then located at what is now 150 Benefit Street, with the front facing North Main Street). As he reached the State House, Providence’s United Train of Artillery fired a salute with their cannon. When he arrived at the State House the streets were lined with women in white holding in their hands branches of flowers. As Lafayette walked up the State House steps, they strew his path with flower petals. At the top of the stair landing, he was greeted with affection by Colonel Stephen Olney. Olney had served in the Second Rhode Island Regiment of Continentals at the Battle of Rhode Island and as commander of the Rhode Island Regiment under the command of Lafayette at the Siege of Yorktown in 1781.

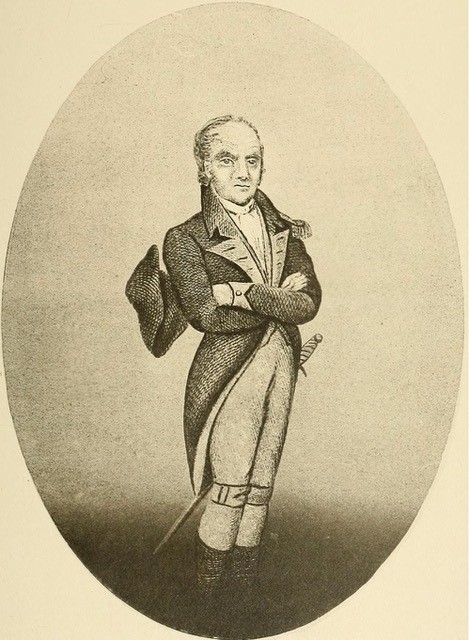

Stephen Olney, from an 1822 bank note. Olney was a veteran officer who met with Lafayette in 1824 (Gloria Schmidt Collection)

After being greeted by state and town Officials in the Senate Chamber of the State House, Lafayette walked to his place of accommodation, Sanford Horton’s Globe Tavern at 81 Benefit Street. During a meal at the hotel dining room recollections of the War for Independence were shared. After the meal General Lafayette reviewed the troops and shook hands with all the “principal officers.” His carriage was placed at the end of the line and brought him back to Horton’s. This tavern, then called the Golden Ball, was also where Lafayette stayed in 1784 when he was entertained by tavernkeeper Henry Rice. The next day Lafayette was on to Boston and more celebrations.

Lafayette was not done with Rhode Island. During his stop in Vermont in June 1825, he heard about Colonel William Barton being held in debtor’s prison in Danville, Vermont, for the last thirteen years. Lafayette knew that Barton had commanded the party that made the outstanding capture of Major General Richard Prescott of the British Army from his quarters at the Overing House in Middletown in July 1777. As one of his last acts before departing the United States for France, Lafayette wrote a draft for the payment of Barton’s debts. Barton soon travelled to Providence to once again be with his wife and children.

Lafayette’s First Visit in 1778

“Lafayette, in 1824 told the late Mr. Zachariah Allen as he rode with him in a carriage across the border from Connecticut, ‘In this state I have experienced more sudden and extreme alternations of hopes and disappointments than during all the vicissitudes of the American war.’” This quotation is part of a speech given at the dedication of a Battle of Rhode Island Memorial at the Christian Union Church in Portsmouth. The phrase “sudden and extreme alternations of hopes and disappointments” aptly captures Lafayette’s experiences during the Rhode Island Campaign in 1778. In short, there was hope in the new French alliance with the Americans and that the two allies could seize Newport and the rest of Aquidneck Island from the British; but then there were disappointments when the French fleet departed Rhode Island to repair their ships after a terrible storm at sea.

In the summer of 1778 Lafayette brought a detachment of Continental Army troops from General Washington’s main army (then based on both sides of the Connecticut and New York border) to assist Major General John Sullivan in the Rhode Island Campaign, a joint French and American effort to free Newport and the rest of Aquidneck Island from British occupation—and to capture the British garrison there.

A letter Washington wrote from White Plains, New York, on July 22, 1778, contained the orders:

“Sir, You are to have the immediate command of that detachment from this army which consists of Glover’s and Varnum’s brigades and the detachment under the command of Colonel Henry Jackson. You are to march them by the best routes to Providence in the State of Rhode Island. When there, you are to subject yourself to the order of Major General Sullivan, who will have command of the expedition against Newport and the British and other troops on the islands adjacent.”

Lafayette reached Providence with 2,000 men on August 3rd and 4th. On their way, Lafayette and his men camped by Angell’s Tavern in Scituate. There his men had a chance to wash and refresh themselves with the spring that became known as Lafayette’s Spring. On August 5th, Lafayette was aboard the French flagship, Le Languedoc, then stationed outside Narragansett Bay, to meet with French commander, the Comte d’Estaing. The French fleet was waiting off Point Judith; d’Estaing provided Lafayette with the 64-gun ship Provence to bring him back to shore.

There is some documentation for where Lafayette stayed in Rhode Island at this time. There are also other homes that have “Lafayette Stayed Here” legends that have come down through time.

The American forces gathered in Tiverton, close to the Howland Ferry. By August 6, Lafayette and his troops had marched to Tiverton where he is said to have stayed at the Abraham Brown House on Main Road (close to what is now Lafayette Street). Local stories say he occupied the northwest chamber on the second floor. This may have been either before the move to Aquidneck Island or it may be that he stayed there after the retreat.

With the arrival of Continental Army forces to reinforce militia and state troops, the waiting French fleet started its operations on August 8, sailing past British batteries in the Main Channel of Narragansett Bay. The British abandoned Butts Hill (they called it Windmill Hill) and other strategic locations in northern Aquidneck Island. On August 9, Sullivan’s army began crossing the Sakonet River to Aquidneck Island. His troops moved into Butts Hill Fort and Sullivan made it his headquarters. The diary of the Reverend Manasseh Cutler, who served as chaplain for General Jonathan Titcomb’s Brigade of Massachusetts soldiers, provides a few glimpses of what Lafayette and others were doing on the island before the Battle of Rhode Island. His entry for Sunday, August 16, gives us one location of Lafayette’s quarters in Portsmouth. “Went in the afternoon with a number of officers to view a garden near our quarters, belonging to one Mr. Bowler, the finest by far I ever saw….” Cutler goes on to describe the gardens to the house owned by merchant Metcalf Bowler. The last line in this diary entry reads, “The Marquis de la Fayette took quarters at this house.”

Cutler’s entry for Monday, the 17th, also refers to the Marquis. The British had been firing artillery at American siege lines since early in the morning and Cutler, with General Titcomb, had been observing enemy lines from the top of a house. Cutler wrote, “stood by the Marquis when a cannon ball just passed us. Was pleased with his [Lafayette’s] firmness.”

Metcalf Bowler’s mansion has been torn down and his once magnificent gardens destroyed, but there are two homes in Portsmouth with Lafayette legends associated with them. One is the Dennis House on East Main Road, not far from Butts Hill Fort. The southeast room on the second floor has traditionally been associated with Lafayette. A house on Bristol Ferry Road (the Davol Earle House) has also been listed as quarters for Lafayette.

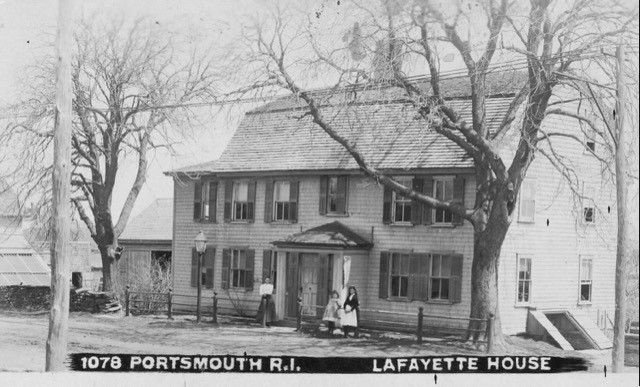

Postcard of the Dennis House on East Main Road, not far from Butts Hill Fort. Tradition has it that Lafayette stayed here during the Rhode Island Campaign in the southeast room on the second floor (Gloria Schmidt Collection)

Although the American forces had moved onto Aquidneck Island and had begun siege operations outside Newport, the French naval and army forces were unable to move forward with their attack of Newport. Their ships were damaged in a fierce storm and d’Estaing decided to depart Rhode Island and head to Boston for ship repairs on August 21. The joint French and American plan was sure to fail without the French aid.

On August 28, Lafayette made the six-and-a-half-hour trip by horseback to Boston to meet with d’Estaing. Lafayette could not persuade the French admiral to return to Rhode Island, but he performed good diplomatic work soothing d’Estaing’s feelings after General Sullivan had insulted him in general orders and the Boston populace was upset about the French leaving the American forces on Aquidneck Island. On August 30th Lafayette rode back to Portsmouth in record time and arrived at 11 p.m. To his great mortification, he had missed the Battle of Rhode Island, at which American troops had fought well. During the night of August 28 and 29, the American army had retreated from their siege lines to a defensive line on both sides of Butts Hill Fort. During the day, advance American parties and the rest of the army had held off attacking British, Hessian and Loyalist forces.

After Sullivan ordered his army to evacuate Aquidneck Island, Lafayette took command of the rear guard. He ordered fires built to mislead the British into thinking the Americans were hunkering down. By 3 a.m. on August 31, the American retreat was complete. The British had not attacked again. The young Frenchman wrote to George Washington from Tiverton on September 1 that he was “happy enough to arrive before the second Retreat, but it was not attended with such a trouble and danger as it ought to be, had not the enemy been so sleepy, and then I was once more deprived of my fighting expectations.”

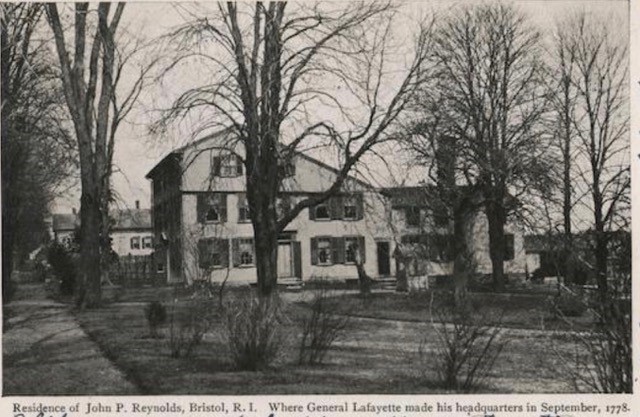

The diary of Colonel Israel Angell of the Second Rhode Island Regiment notes that on September 1, General Varnum’s Brigade in General Lafayette’s detachment passed by boat from Tiverton to Warren. The next day they were in Bristol where Lafayette made the Hope Street home of Joseph Reynolds his headquarters. A plaque on the house reads: “This house built about the year 1698 by Joseph Reynolds was occupied by Lafayette as his headquarters September 1778 during the War of American Independence.” Lafayette’s room was the northwest bed chamber. The southwest room on the first floor was his dining room and office.

Postcard of the Joseph Reynolds House, which Lafayette occupied as his headquarters in September 1778 (Gloria Schmidt Collection)

By September 18th Lafayette had moved on to Warren where his brigade encamped on Windmill Hill. Lafayette’s quarters were at Cole’s Tavern, which has since burned down. On September 28, he was in Boston, on his way to Philadelphia on October 1st.

A Second Visit to Rhode Island (1780)

The Marquis’s second visit to Rhode Island was in the summer of 1780. Washington sent Lafayette to carry his greetings to the Comte de Rochambeau. Rochambeau commanded a large French fleet and army that arrived in Narragansett Bay on July 11. Lafayette was in New Jersey when he received his orders from General Washington to greet Rochambeau. Lafayette’s route led him through Peekskill, Danbury, Hartford, Lebanon and finally arriving in Newport on July 25th. Lafayette remained in Newport with Rochambeau at the Vernon House, located at 46 Clarke Street. The Vernon House was owned by Newport merchant and slave trader William Vernon. It was Rochambeau’s headquarters until July 31st.

Letters “to” and “from” Lafayette during this time give us an idea of his actions during this visit. Lafayette is working with both the Count de Rochambeau and Continental Army Major General William Heath as the representative of General Washington.

Lafayette wrote to Washington that the French looked upon Rhode Island as a point to be kept for receiving their fleets and the re-enforcements of their troops. When the French came ashore, they had 1,300 sick soldiers from the Atlantic crossing.

Through various sources and spies the American and French forces learned that British forces were intending to sail from New York and attack Newport before the French could establish their defenses. Lafayette himself was one of those carrying intelligence of this planned attacked. This news sparked plans to bolster the defense of Newport and the rest of Aquidneck Island. Lafayette helped to prepare Butts Hill as a communications center with the American forces on the mainland. Rochambeau also requested the help of New England militia to serve for three months to help the French defend Aquidneck Island. Rochambeau wrote, “As to the three month militia . . . from the State of Massachusetts and Rhode Island, and also the regiment commanded by Col. Greene [this is the First Rhode Island, whose rank and file were all soldiers of color), the French General requests that they may be collected as was heretofore settl’d to the north end of the island [Aquidneck Island], where they will make some works for the security of his communication with the continent.”

In a letter to George Washington on July 29th, Lafayette comments:

“I went yesterday to the North end of the island, and had the works repaired in Such a way ‘at least they will be soon’ as to keep the communication by Howland’s Ferry for 8 or 10 days after the enemy will possess the island. I have also desired Col. Greene in case they appear, to run up the boats to Sledzel [Slade’s] Ferry. Signals have been established from Watch Point [Watch Hill] to Connancicut [Jamestown]. All those arrangements I have made with the approbation and by the orders of General Heath.”

Lafayette was concerned about the state of the works at Butts Hill.

“To William Heath – Newport August 2nd 1780

On my coming into the town, I found that Count de Rochambeau was going to Butts Hill, and you easily guess that I did not like the plan. Our works are so disordered, and his dependence upon them so great . . . .

As to the Boats they might be collected under the Care of a guard and people employed in Repairing of them. In the same time our fashines [fascines, which were wooden sticks bundled together to bolster defensive fortifications], cannon, etc. should be ready at the North end of the Island with a Corporal’s guard.

I also believe we ought not to go through the militia camp, but meet you at the fort with some of their officers whom we will introduce to the Count.

Don’t you think, my dear Sir, that we ought to put everything in a good trial. As to the tools, workmen, etc. against a time the Count will come.”

All these preparations were useful in discouraging the British from attacking. In his article on spies warning the French of an impending British attack, historian Christian McBurney makes the point that these preparations served as a deterrent to the British.

“These militiamen and improvements in Newport’s defenses were noticed by Loyalist spy Thomas Hazard and British naval observers, which helped to discourage Admiral Arbuthnot from cooperating with Clinton, forcing the commanding British general to drop his plans against Newport. Accordingly, these various American spy efforts played a substantial role in thwarting the British attack on Newport.”

Lafayette was anxious to move on from Rhode Island and join the war effort to the south. He left without requesting permission from General Heath. By August 7th Lafayette was back in Peekskill, New York, commanding his troops.

A Third Visit to Rhode Island (1784)

After the close of the Revolutionary War, Lafayette made a third trip to Rhode Island. In October of 1784 he arrived in Providence. The grandeur of this visit was similar to the welcome he would encounter on his 1824 visit. The Providence Gazette edition of October 20, 1784, reported:

“Last Saturday Afternoon (October 23) the Honorable Marquis de la Fayette arrived here from Boston. He was met a few miles from hence by a Number of principal Inhabitants, and received at the Entrance of the Town and escorted in, by the United Company of the Train of Artillery under arms. On his Arrival he was welcomed by a Discharge of 13 Cannon at the State House Parade, the Bells were rung and at Sunset, the Salute was repeated by heavy Cannon on Beacon Hill.

The Marquis having visited Newport returned from thence on Monday Evening and on Tuesday partook of an Entertainment at Mr. Rice’s Tavern at which were present his Excellency the Governor, his Honor the Deputy-Governor, both Houses of Assembly, a Number of respectable Inhabitants, Officers of the late Army &c. After dinner the Marquis set out for Boston and was again saluted with 13 Cannon.”

“On Monday last (October 25) the Society of Cincinnati of this State convened at Mr. Rice’s Tavern where an elegant Dinner was provided upon the Occasion; and having finished the Business of their Meeting they were honored with Company of his Excellency the Governor his Honor the Lieutenant Governor and the Honorable the Marquis de la Fayette accompanied by the Chevalier De L’Enfant.” Thirteen toasts were given.”

It is apparent from the above report that Rhode Islanders had a great affection for Lafayette, even though it was only a year after the end of the War of Independence.

During his four visits to Rhode Island, Lafayette assumed a variety of roles. During the Rhode Island Campaign in 1778, Lafayette was a commander of American troops and a negotiator/diplomat with French admiral D’Estaing. His negotiations had failed, but he was still a symbol of heroism in safely leading the last of the piquet off Aquidneck Island at the end of the Battle of Rhode Island. In 1780 Lafayette served as the representative of Washington to the recently arrived French general Rochambeau. He was instrumental in having the works at Butts Hill Fort repaired and useful for communications in case of a British attack. By 1784 and 1824, he was the adored “friend of America.”

In his letter from camp in Warren in 1778, Lafayette wrote that he longed to fight for freedom with the Americans and that he desired to “serve her in any time or any part of the world.” Americans still honor his service to the cause of American freedom.

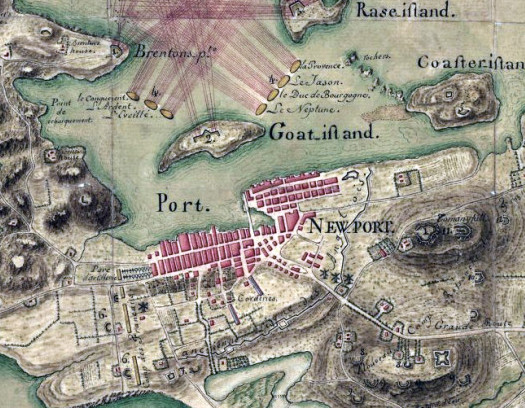

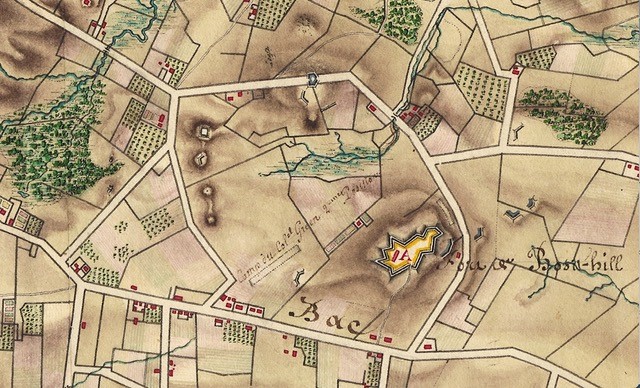

Excerpt from a map prepared by Louis Alexandre Berthier for the Comte de Rochambeau, probably in 1780. The image shows the location and structure of Butts Hill Fort and the location to the south where the First Rhode Island Regiment camped (Library of Congress)

Sources:

Allen, Zachariah. “Conversations with Lafayette,” Rhode Island Historical Tracts #6, Sidney Rider, Providence, Rhode Island, 1878. This is also available online at https://navigator.rihs.org/rhode-island-a-bibliography-of-its-history/the-centennial-celebration- of-the-battle-of-rhode-island-at-portsmouth-r-i-august-29-1878-comprising-the-oration-by-ex- united-states-senator-samuel-g-arnold-a-letter-by-sir-henry-pigot-the-en/

“Boulder Marks Place of Fight.” Newport Herald, August 29, 1910. Accessed at https://portsmouthhistorynotes.com/2023/07/22/marking-the-battle-site-dar-monument/

Cutler, William P., and Perkins, Julia P., editors. Life, Journals and Correspondence of Reverend Manasseh Cutler. 2 Vols. Cincinnati, OH: Robert Clarke & Co. 1888.

Field, Edward. The Diary of Colonel Israel Angelo Commanding Officer, 2nd Rhode Island Continental Regiment during the American Revolution. Providence, Preston and Rounds. 1899.

Gottschalk, Louis. Lafayette in America. Arveyres, France: L’Esprit de Lafayette Society, 1975.

Idzerda, Stanley J. and Robert Rhodes Crout, editors. Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution, Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790. Vols. 2 and 3. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1983.

Levasseur, Auguste. Lafayette in America in 1824 and 1825. Translated by Alan R. Hoffman. Manchester, NH: Lafayette Press, 2006.

McBurney, Christian. “The Culper Spy Ring was not the first to warn the French at Newport.” Smallstatebighistory.com. Accessed at http://smallstatebighistory.com/the-culper-spy-ring-was-not-the-first-to-warn-the-french-at-newport/

McBurney, Christian. Kidnapping the Enemy: The Special Operations to Capture Generals Charles Lee & Richard Prescott. Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2014.

McBurney, Christian. The Rhode Island Campaign: The First French and American Operation in the Revolutionary War. Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2011.

Preston, Howard. “Lafayette’s Visits to Rhode Island.” Rhode Island Historical Society Collections (January 1, 1926).

Providence Gazette, October 30, 1784, and August 25, 1824.