[Note from the Editor: The following interview appeared in “In the Wake of ’38, Oral history interviews with Rhode Island survivors and witnesses of the devastating hurricane of September 21, 1938.” The booklet of interviews was released in the Spring of 1977, and is available in some state libraries, including in South Kingstown. It was sponsored by the Rhode Island Committee for the Humanities and South Kingstown High School. The project directors were Linda Wood, then a librarian at the high school, and Judith Preble, then an English teacher at the school. Eleven South Kingstown High School students interviewed numerous eyewitnesses about the personal, social, economic, ecological and political effects of the Hurricane of 1938. The Editor encourages more high schools in the state to undertake oral history projects.

This is Part II of an interview with Ann Crawford “Nancy” Allen Holst (1908-1997), a feisty, clever and strong-willed woman who in 1938 was the State District Forest Fire Warden for Kent County. She was, according to one source, the first female fire chief in the nation. She was also one of only two licensed female pilots in the state in the early 1930s. As Nancy Allen Holst discusses below, in the immediate aftermath of the hurricane, she put her skills as a pilot to use to spot dead bodies floating in the water.

Nancy Allen Holst was interviewed in 1977 by Jane Hutton, then a South Kingstown High School student (and former classmate of the Editor’s and a long-time friend). Part I addressed the impact of the hurricane that Holst witnessed. Part II, below, focuses on the devastating impact the hurricane had on the state’s forests and timber industry, particularly in Exeter, West Greenwich and Coventry. It ends with a discussion of the role of government, the lack of forewarning about the storm, and prospects for a future deluge.

Mrs. Nancy Allen Holst, interviewed by Jane Hutton. April 27, 1977.

JH: Mrs. Holst, what was your occupation in 1938?

NH: I was the State District Forest Fire Warden for the Department of Agriculture and Conservation, Division of Forest Parks and Parkways.

. . . .

JH: . . . .[W]hat damage seemed the most striking to you?

NH: The damage to the trees. Now, I don’t mean the trees around the houses. Of course, that was pathetic. But I mean the trees that I was interested in–the timber trees in the western part of Rhode Island. That was absolutely appalling. The 1938 Hurricane timber blowdown, as estimated on October 4th, 1938, in Rhode Island was 400 million boardfeet, mostly white pine. New Hampshire, who also got the hurricane, had 1 billion, 222 million boardfeet of white pine down, 233 million of other soft woods, 212 million feet of hard woods. Now, I’ll repeat those figures to give you an idea of the completeness of the blow-down. The entire New England area’s salvageable timber was estimated on January 16, 1939 at 2 billion boardfeet, Rhode Island having 80 million of that. You see, Rhode Island’s long, narrow white pine belt stretched through Exeter, West Greenwich and Coventry and was this state’s richest natural resource. It supported a good-sized lumber industry. The big trees, five of which held enough lumber to build an averaged size house. . . . you see, it takes about 5,000 feet of lumber to build the framework of a house, and those lofty trees gave about a thousand feet each tree. They were one of Rhode Island’s glorious sights. In three hours on September 21, 1938, that timber resource and an industry were wiped out. It was if the saddest parts of the 1938 Hurricane. Neither will ever return to Rhode Island.

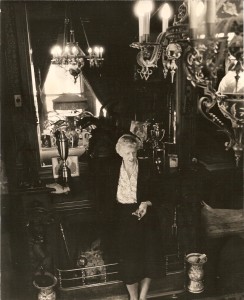

Nancy Allen Holst speaks to a tour group in 1th 1970s in the library of her Clouds Hill home, which is currently open to the public as a museum under the auspices of her daughter, Anne D. Holst (Collection of Anne D. Holst and Clouds Hill Victorian House Museum)

Now, the final figures on that timber blowdown: in November of 1939 the sale of 600 million boardfeet of New England hurricane-fell lumber, for $14,400,000 was believed to be the largest transaction of its kind in United Stated history. Rhode Island’s share of the above was between twelve million and thirteen million boardfeet and the selling price was $24 a thousand. So there was some salvages, as you see.

Now, the interesting part of those figures is the fact that FDR notified the Forest Service to come into New England and he had organized the North-Eastern Timber Salvage Administration. They directed the salvage work, that was the training of the workers who were to handle this tremendous volume of downed timber, and set up what they call log ponds, because you cannot leave timber stored on the ground because the bugs get in it after the cold weather goes. You have to keep it in water.

JH: That doesn’t affect the timber—keeping it in the water?

NH: No. It has no effect. The bugs can’t reach it in the water. It will keep indefinitely. So they had to select throughout New England these pond sites to store the logs. The Forest Service men moved in en masse. They moved practically the whole of the Forest Service into New England. Of course, there were a lot of people pretty disgusted with the Depression and the government’s handling of everything and FDR was losing voting appeal. They said that he grabbed this as a way of regaining it. Now, whether that’s so or not, have no idea. But that was one of the commonly-voiced sentiments. I do know we never could have handled it ourselves without this expertise of the foresters from right across the country. They came, from the West Coast, they came from the Deep South, they came from Michigan, they came from all over.

JH: Did you take part in this?

NH: This is the Rhode Island Forest Emergency Manual. I was solely connected with the Fire Preparedness Section. The Forest Service was solely to help us. They would not come in on a fire and the State District Wardens were still in charge. A State District Warden was in charge of the county, and all the operations were under him. . . . or her. So that is the set-up. We had this large manpower expertise brought in to us and everybody was very grateful for it. Though, of course, there were some that didn’t feel that way. The Rhode Island Lumber Unit was organized—the Rhode Island lumber industry’s committee–and they operated. Mr. A. Studley Hart of West Greenwich was elected the temporary chairman of the group and Freddie Martin of the U.S.F.S. was the temporary secretary. Well, they got a lot of flak on that because here in January of 1939 Mr. Hart maked [sic] the headlines defending the handling of Rhode Island timber salvage. It’s like any government program. You’re bound to get a lot of flak, no matter how hard you try.

I’d like to read you this story by Leonard Warner of the Providence Journal, who was the agricultural writer, and Don Goodwin:

Thousands upon thousands of pines, which under normal circumstances the lumbermen would have milled gradually to meet the demand, now have to be finished up as quickly as possible. There is no estimate of the damage but the native lumber dealers say it will run into millions of dollars to say nothing of a lost industry. Most of the state’s soft pine is being sold to box factories, but some is used for framework purposes in house construction. It takes about five thousand feet of lumber to build a framework of a house, and some of the lofty trees are giving the millers about one thousand feet. Not a single pine of any consequence remains for Mr. Tarbox. Tarbox, a tall, elderly man who knows the pine belt as mother knows her icebox, took time out from milling yesterday to tramp through his 200 acre pine grove. Everywhere huge pines lay stretched—fifty, seventy-five and a hundred feet long. Not a single pine of any consequence remains.

He led the walk to the south to Exeter where a large pine grove, bigger than his own, belonging to his daughter, Mrs. Pearl Sunderland, was wiped clean. Root mounds, pulled from the earth by the fall of the tall trees, lay on their side, as high as twenty feet in the air. Boulders weighing a ton remained imbedded upon the roots.

“No, sir. This generation will never see pines as tall as we did. It will take scores of years for them to grow again.”

His nephew, Howard Barber, also a lumberman, nodded in agreement as he ran his hand up the gummy side of a broken pine, almost tenderly.

They are a lumber family—these Barbers and Tarboxes—and to see their forests destroyed hurt deeply. They always replanted as they cut to assure pines for a future generation but now that is almost impossible. Their mills have cut as high as between 1200 and 1300 feet an hour, or about 1½ million feet a year. With soft pine selling at between 25 and 30 a thousand, that’s pretty good business. “It’s impossible,” said the neighborly Mr. Tarbox, “to visualize this forest as it was. It was beautiful. You see that spot over there?” He was pointing to an area near a pond in back of his home. “I was never going to cut that. That was my grove, and as long as I lived it was going to stand tall and beautiful. Now it’s gone.”

And that was very representative of all the lumbering industry. Now you say, well, there’s a lot of lumbering going on; Mr. Turnquist up in the northern part of the state has got a good sawmill going. But the smaller industries, like the shingle mills, are gone forever. You’ll never see them again. In the town of Washington, over in Coventry, there was a charming shingle mill, run by a huge diesel engine, that I always liked to stop and see. The pines were brought in bolts. They’d just feed into this shingle mill and come out all beautiful nice shingles.

I don’t know. I don’t know why we had to have the hurricane. It was a tremendous loss.

JH: What was done with all the wood that they had to pile up?

NH: Well, that is interesting. The finished lumber was stacked in what they call yards. There’s a picture of how they stacked them. This is dated November, 1939. The lumber continued to be produced up until the summer of 1940, pretty well cut by then. The government had bought all this lumber through this Northeastern Timber Salvage Administration. They didn’t dare dump it all on the market because it would have hurt the West Coast markets and the Southern markets, so they were stockpiling it. And then along came Pearl Harbor and the tremendous demand for wood. I don’t know if you know that it takes five trees behind every soldier that a country puts out.

JH: Why is that?

NH: Because of the necessity for constructing bases, packaging all of the ammunition and other things. You’ve got to have wood to do that. And that’s why the figure was given in World War II that it took five trees to outfit every soldier that the United States put in the field.

The government had this tremendous stock of lumber and were able to throw it, right away, into the war effort and it was one of the hidden weapons that the United States had. No other country had such a stockpile that they could suddenly call upon.

JH: So you think that was an advantage in the war?

NH: Oh my, yes. It was one of the things that swung the war in our favor that we could get into action so quick.

Here is a list of the uses of the timber—”Rhode Island’s Most Useful Forest Trees During the War.” Now the big heavy oak timbers were made into landing platform mats for our northern bases. Piling was used in Newport, Quonset—right up and down the coast. Railroad ties were most necessary because the railroads were moving such tremendous amounts of. . . . they had to have stakes for railroad cars–flatcar stakes–to ship things with and, of course, bridge timbers. These are the things that were made from Rhode Island timber during the war; tent pegs, tent stakes, boxed and crates, insulating board, fence posts—they had to have 250,000 fence posts just to fence the Sun Valley Seabee Range up here in East Greenwich.

So, you see that the Rhode Island timber did go on the warpath, and it was a very great asset—this New England timber that came from the blowdown of the Hurricane of ’38.

JH: So you think this helped the Rhode Island economy a lot during that time?

NH: I think it did. The share of Rhode Island’s money from the sale of salvageable timber wouldn’t have been too effective on the economy, but the fact that we were getting the bases and the personnel and the trade form all of this Navy activity in Rhode Island boosted the economy out of sight.

. . . .

Role of the Government and Lack of Forewarning

JH: Do you think the government dealt well with the disaster?

NH: I think they did very well. I really do. Of course, you have many facets there and I can only speak of two—the timber industry and fire preparedness. We got excellent support and I think it was well-managed. I think it was very well-conducted. Now the American Red Cross is not connected with the government, and yet it is. It’s a national thing and I have nothing but criticism for them.

JH: Why is that?

NH: The National Disaster Team was . . . well, frankly, incompetent. That’s all I can say. They hadn’t the faintest idea of what they were doing or what they should be doing. They were partying a great deal of the time over in the Biltmore Hotel and couldn’t be reached when we needed them the most. The local chapters and branches handled things pretty well—Westerly was splendid. East Greenwich had a tremendous job of resettling the whole of what they called Scalloptown, which was a chanty town down on the cove. That, of course, was wiped out so they had to resettle all these families and provide houses and equipment. They resettled them-up in what was then the sticks of East Greenwich, up in Frenchtown section on Shippeetown Road, a whole section they bought there and built little houses and put them in there. And I thought it was a splendid thing but the people didn’t like it. They wanted to go back where they were before. It’s very hard to resettle people we found out.

JH: Were people hard to get out of the houses that were damaged?

NH: Well, there weren’t any houses. I mean they were just gone. There was no problem moving them out–they were just gone. There was nothing, so that did not core into it. They were given these nice brand new little houses and a jag of land and hopefully they would have a garden and become a little bit more self-supporting than they were, because most of them were on welfare anyway. But they resented it and wanted to get back to the village as quick as possible.

. . . .

JH: Did the government take any lasting measures as a result of the hurricane?

NH: Not that I know of. Well, of course, the Weather Bureau, I think has never been the same. I don’t know that they are any better today than they were then—even with their satellites and so forth. I still think that they lost track of that storm last summer and didn’t have the faintest idea of where it was. I do know that all the while there was a Weather Bureau at Quonset Naval Station and their forecasts were usually completely different that Hillsgrove U.S. Weather Station. I think that another hurricane could sneak up on us just as easily as the ’38 one did.

JH: Nobody really knew that it was a hurricane though, did they, in ’38?

NH: Well, when the wind starts blowing the way it did, I think you would have to admit it.

JH: There was no warning or preparation, was there?

NH: No. There wasn’t any. No, I won’t say that because I had a friend who was a Nova Scotian, captain of a yacht down in East Greenwich, and he was an old seadog—he’s long dead now. But about two o’clock he told a friend of mine we were going to get one heck of a storm. He went down, got his crew and went aboard the yacht–it was a very large schooner yacht with power–and he took that boat away from its moorings and got it away from everything else in the outer bay and he rode out the storm, his engine running all the time. He brought that boat through without one single bit of damage. Now, if he knew we were going to have it, somebody else should. Of course, they have some pretty vile weather down Nova Scotia way—they really get it—and he knew. So there was something there—there was a warning.

. . . .

There were a lot of people that took out small boats that they could take and preserved them. Everybody that left them in lost them.

Prospects for Future Hurricanes and Preparedness

I think the dam in Providence, the hurricane barrier at Fox Point, has never had a sufficient test. I don’t know whether it would work or not. The power of the water driven by the tide and hurricane winds is absolutely tremendous. You see, it comes from the south, pushed by these winds, and that in itself wouldn’t be so bad, but you’ve got a whole volume of water being pushed and its hits the continental shelf right offshore, and it comes up and it gives it that much more height and force. It’s the continental shelf that makes a tremendous impact.

JH: Do you think more of these things should be tested now in preparation for another hurricane storm like this?

NH: No. To my knowledge the ’38 Hurricane was the first since 1815. Then we had three or four in a row in ’44 and ’54. I don’t look for any more as severe as the ’38 Hurricane for another hundred years.

[Banner Image: Downed trees uprooted by the Hurricane of 1938, in New Hampshire (Collection of NOAH)

For further reading:

For a short summary of the remarkable career of Anne Crawford “Nancy” Allen Holst, go to the website for Clouds Hill Victorian Museum: http://www.cloudshill.org/chiefnancy.html

The Editor would like to thank Anne D. Holst, daughter of Nancy Allen Holst, for providing some information for the introduction to this article and for making available an image used in the article.