[From the editor: This article quotes at length from chapter 8 of the following book published in 1904: Half a Century with the Providence Journal, Being a Record of the Events and Associates Connected with the Past Fifty Years of the Life of Henry R. Davis Secretary of the Company, by The Journal Company (Providence, RI: Privately Printed, 1904), pages 195-199. Minor edits have been made to be consistent with modern usage, spelling, and grammar. Some clarifying material has been added in brackets. The last paragraph below is from a later part of the chapter. The Journal was then published in the morning and the Evening Bulletin in the afternoon.

One of the storms discussed is The Great Blizzard of 1888, from March 11 to 14, 1888, one of the most severe recorded blizzards in United States history. The storm paralyzed the East Coast from the Chesapeake Bay to Maine. Another was the flood of 1886. The storm of February 11 to 14, 1886 was one of the twelve great storms in New England, according to a federal government paper published in 1964.]

The flood of 1886 tested the resources of the Journal for the collection of news, especially in this part of New England, to which the overflow was mainly confined. The rain began February 10 and continued for thirty-six hours, until February 12, while the fall of rain, sleet, and melting snow amounted to 8.13 inches, a record which has seldom been surpassed in the United States.

A horse-drawn sleigh is pulling riders on Bellevue Avenue, Newport, after a snowstorm, circa 1900 (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

There was nearly two feet of drifted snow on the ground, which had been frozen hard, so that the rising waters had no other means of escape except to flood the valley. The storm appeared to be most severe in the area drained by the Moshassuck River, which is ordinarily a comparatively small stream. The Woonasquatucket River was also compelled to take a tremendous addition to its usual volume, and the tide poured by both these streams into the Old Cove basin [in downtown Providence] nearly reached the pavements of Exchange Place.

The first signs of the magnitude of the flood were apparent Thursday afternoon, February 11, when reports from surrounding villages brought the information that the water in every stream was very high. The Bulletin for Thursday, however, went to press without special efforts to describe the situation. During the evening the Moshassuck River began to approach the danger point; so, reporters were sent in every direction about the city, but in many cases their tedious jaunts did not bring results for publication until Friday’s Bulletin.

By Friday streams overflowed and washed roads and destroyed bridges, buildings along the rivers were flooded, dams were carried away or injured, and the railroad tracks became so dangerous that the running of trains had to be stopped. The Moshassuck River, where it reaches the vicinity of the Charles Street railroad crossing, swept over the street upon the railroad tracks, and from that point to the Smith Street Bridge a four-foot current rushed along the rails in the “cut” and emptied again into the Moshassuck at the northern end of Canal Street. Of course, this blocked all north-bound trains, which had to be held in the [Providence rail] station.

The flood in the valley of the Moshassuck reached its height Friday forenoon, but some of the other basins drained by the Providence River, continued to rise until that night, when the most damage was done. All communication with Boston and Worcester by railroad was cut off nearly all-day Friday, although some trains, preceded by wrecking apparatus, went through that night. In the meantime, persons who were anxious to reach Boston started in a party wagon, leaving Exchange Place at 11 o’clock that forenoon.

There were not many long-distance telephones in use at that time, and comparatively few other lines running outside the city, and these were in some cases carried down by the flood. The telegraph wires worked fairly well, but they were in such a condition that only important news was transmitted. The Journal’s reporters and correspondents about the city were compelled, almost without exception, to bring in their own news because it could not be sent over wires and-messengers were not sure of getting through. The Bulletin, nevertheless, went to press with crowded columns describing the storm, and printed 33,730 copies—a large number for that time.

The total loss through the flood probably reached a half-million dollars, for not a town in the State escaped the consequences of the overflowing of the streams. Roads had to be remade, bridges rebuilt, the railroads repaired and cleared of debris, and manufacturers were compelled to repair their plants and make up losses on stored stock and machinery. The city of Providence had to restore streets and partly destroyed bridges. The mayor of the city, the late Thomas A. Doyle, was on the scene of the Moshassuck floods all Thursday night and Friday forenoon, and other officials who could do anything to save property were on duty for thirty or more consecutive hours. They early perceived the danger threatened by the famous Georgiaville Dam and ordered those having charge of it to let off all the water possible. [Georgiaville Pond in Smithfield was a manmade reservoir on the Woonasquatucket River in the 1850s; out of concern that its dam could break and kill people below it, it was deconstructed in 1894]. It was fortunate that the tide was running out when the greatest rush of waters came.

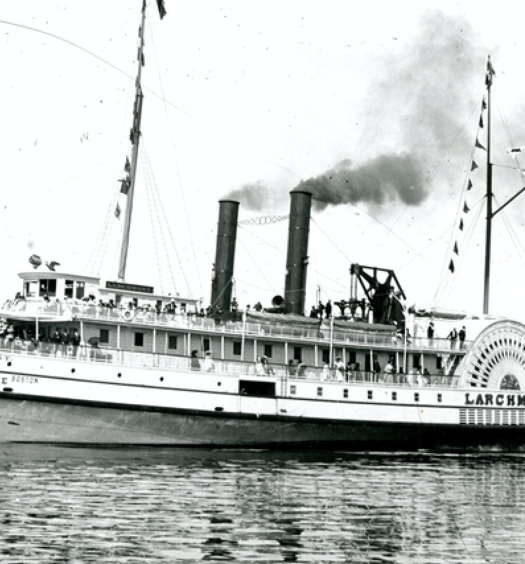

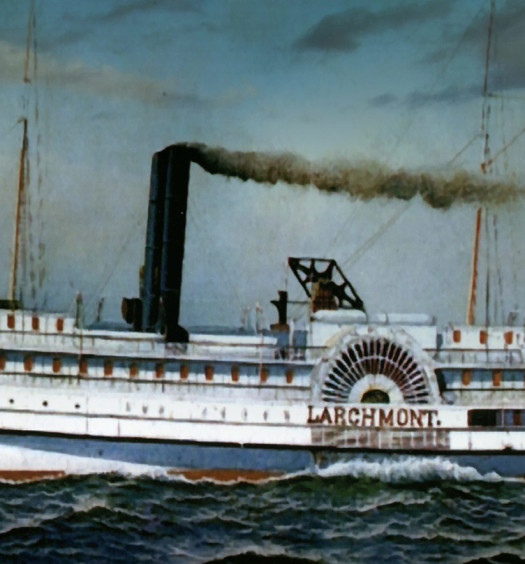

Another test of the newspaper’s ability to surmount obstacles in handling news was made in the famous blizzard of 1888, when New York City and southern New England were storm-bound for four days. The storm reached Providence Sunday evening, March 11, when the barometer began to fall, and it continued in its downward course until Tuesday morning when it showed a pressure of 28.85 at an elevation of 75 feet above the sea, a record seldom equalled in this locality. Only seven inches of snow fell in Providence, but this was whirled by the wind into troublesome drifts. Down the Stonington Road [The railroad line from Providence to Stonington Connecticut, where passengers would then sometimes take a steamer by water to New York City], as it was then called, and along the whole of the Shore Line to New York [then part of the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad system], the fall was much heavier, so that the drifts completely blocked the trains. In New York City the storm was even more severe, and completely tied up the steamship, railroad, and other transportation service of the metropolis. The area of the barometrical depression was from one hundred miles west of New York City to north-central New England and the ocean.

As New York is the center of general [i.e., national] news, the effect of the blizzard on that city was apparent in the newspaper offices generally. Several long-distance telephones could be worked from Boston to Albany and thence to New York City, but the messages were transmitted with the greatest difficulty and hours occasionally intervened between the periods of open-line operation. With this unsatisfactory exception, Providence had no means of communication with New York City from Monday to Friday by usual methods.

The character of the situation was realized at the Journal office Tuesday forenoon, when provision was made to get into touch with New York as quickly as possible. Reporters were sent to various points, particularly to Stonington, where it was supposed that the first news from New York might come by boat. One reporter spent two days and a night there waiting for the first boat, which did not arrive until 4 o’clock Wednesday afternoon. By this means the Journal was able to secure the news for Thursday morning, although it was several days late.

The Bulletins of Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday printed no fresh news that was not entirely local. The Journals of Tuesday and Wednesday were likewise lacking in general dispatches. But when the reporter secured newspapers from New York City by the Stonington boat Wednesday afternoon, the Associated Press was able to glean a record of 8,000 words of the world’s happenings, which were put on the wire that night for the New England papers. This was probably the heaviest report sent out from Providence in one night by that organization, either before or since the blizzard. This fresh information included the announcement of the death of the Emperor of Germany, a dispatch that should have been published Monday afternoon. This boat continued to be the only means of communication between New York and a large part of New England for several days.

The condition of travelers on the road to New York had been rather serious, and the report that several invalids on their way to Florida had suffered from the exposure induced a reporter to tramp nineteen miles in the snow after a train which was plowing its way to that city. The old ferryboat that then carried the trains across the Thames at New London was loaded down with two trains full of passengers, for whom food had to be sought in the vicinity. East River was frozen over in New York City, which was in danger of a famine for several days.

Although Providence was shut out from a part of the world by this blizzard, the storm was not severe enough here to cause much suffering, although the poor train service to the south of the city was a great inconvenience. Nearby towns were not cut off as they had been by the floods of 1886 and the telegraph lines to Worcester were intact: The Journal kept men on the scenes of the digging out of trains between Providence and New York until communication was open. But during the interruption of telegraphic reports of Congressional speeches and incidents in European life the local force proved that the paper could be made interesting with only city news, and it was some satisfaction to reverse the order that prevailed in the previous generation—when home problems were hardly considered worth mentioning, but European and national affairs were printed at length.

Photograph of Pawtuxet Falls, on the western side of Pawtuxet Bridge looking north towards buildings on the Cranston side of the river. The water is very high during a 1919 flood (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

Another case where difficulties in the prompt collection of news which seemed unsurmountable were overcome was in the report of the preliminary hearing given to Lawrence Keegan, when he was bound over to the grand jury for the murder of Mrs. Emily Chambers on the Scituate Hills on September 27, 1894. Keegan was taken before a judge in the isolated village of Richmond [in South County], which was without telegraph or telephone facilities and was located three miles from any line of communication by wire to the city of Providence. There was great local interest attending the case, since the parties were from Providence, and the tragedy was involved in much mystery.

The case was set for October 20, the week of the horse races at Narragansett Park. The Journal company made arrangements with A. H. Barney for the use of running horses from his stables, by which the report was taken as fast as written to the point where the telephone wire passed nearest to the place. Here a telegraph operator tapped the wire placing the instrument in his lap while he dispatched the reports to the Bulletin office as fast as they were brought to him. Two horses were used, Athalena, running from Richmond to Ashland, where she-was-relieved by her mate Jakey Joseph, who covered the remaining distance to the point on the Saundersville Pike where the wire had been intercepted.

The result was that a full account of the proceedings appeared in the Bulletin the same afternoon, the news being received almost as quickly as if the hearing were held in the Providence Court House. The Bulletin was the only newspaper which had the news of the murder case that day, and the achievement was one of the most extraordinary in the history of reporting. To the village people the sight of the racing horses dashing over the road at frequent intervals was indeed a novelty, which could not-fail to impress them with the expedients to which a newspaper may resort when confronted with obstacles.

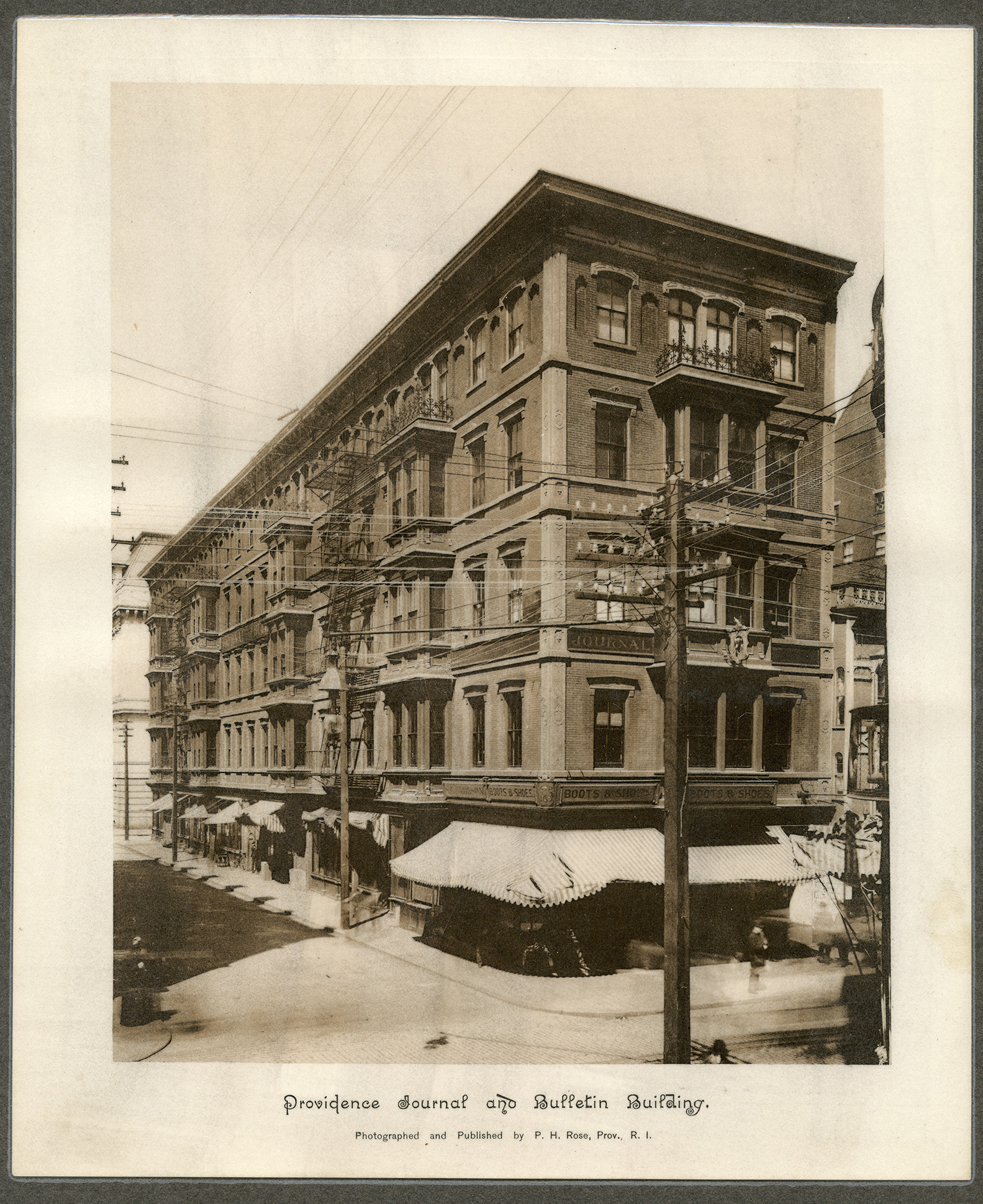

The old Providence Journal and Bulletin Building on the corner of Westminster Street and Eddy Street, used until 1906 (Providence Public Library Digital Collections)

When the fact was established that wireless communications was possible through the air the Journal decided to test the matter practically, to learn what were the possibilities of this system for the collection of news as well as for commercial purposes. In 1903, the Journal established at considerable expense wireless communication stations at Point Judith and Block Island, installed operators there, and transmitted messages to and from the island.