The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House ranks as one of the bloodiest battles ever fought on the American continent. Fought from May 9 to 21, 1864, in central Virginia, it was the second major engagement of the Overland Campaign, a titanic struggle fought in the spring of 1864 between Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee that finally brought the Confederacy to its knees. A tactically indecisive battle, it temporarily saw the Confederates blocking the Union path to Richmond. After two weeks of bloody stalemate, Grant simply continued his never-ending march south to the Confederate capital. The battle was the most savage fought in the Civil War as both sides engaged in rare hand to hand combat with equal determination to hold the line on both sides. Several Rhode Island units were present at the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, including the Seventh Rhode Island Volunteers, who saw heavy fighting on both May 12 and May 18, 1864, the two most important days of the battle.[1]

The Seventh Rhode Island was a veteran combat regiment going into the spring of 1864. Raised in the summer of 1862 from all over the smallest state, the Seventh was first baptized at Fredericksburg in December 1862, losing forty percent of the regiment in a desperate assault against a fortified Confederate position. In the spring of 1863, the Seventh was sent to Kentucky and eventually to Mississippi to participate in the Vicksburg Campaign and the fighting near Jackson, Mississippi on July 13. Although combat losses were light in the West, scores of men in the Seventh became afflicted with disease and dozens died of it; indeed, the Seventh spent much of that fall and early winter recovering in Lexington, Kentucky. For several months, the regiment performed guard duty near Point Isabel, Kentucky guarding Union supply lines into Knoxville, Tennessee.[2]

With his promotion to lieutenant general in March 1864, Ulysses S. Grant, now in command of all Union forces, made his headquarters with the Army of the Potomac, then encamped at Brandy Station, Virginia. Preparing for the decisive campaign to finally crush the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, Grant ordered as many Union forces to join his forces in the east as possible. This included the Ninth Corps to which the Seventh Rhode Island was attached. With these orders in hand, the Ninth Corps left Kentucky and Tennessee and headed for its rendezvous in Annapolis, Maryland.

Arriving in Annapolis, the Seventh was in rough shape after its year-long sojourn in the West. Although a veteran regiment, many men were wearing uniforms with holes in them, Rhode Islanders continued to be discharged or die from the diseases contracted in Mississippi, and even worse for the regiment, no new recruits were sent to fill up the severely depleted regiment. Although the Seventh had left Rhode Island with 960 men in September 1862, only fifteen officers and 264 enlisted men were present to take part in the campaign. Worse still, the command staff of the Seventh was depleted. Several company officers resigned and went home, while a number of others were detached on staff duty.[3]

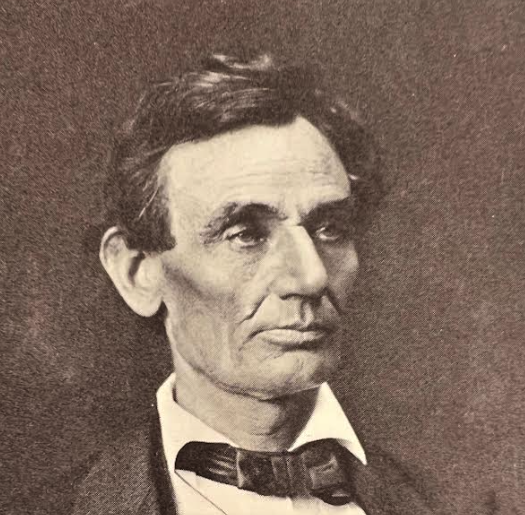

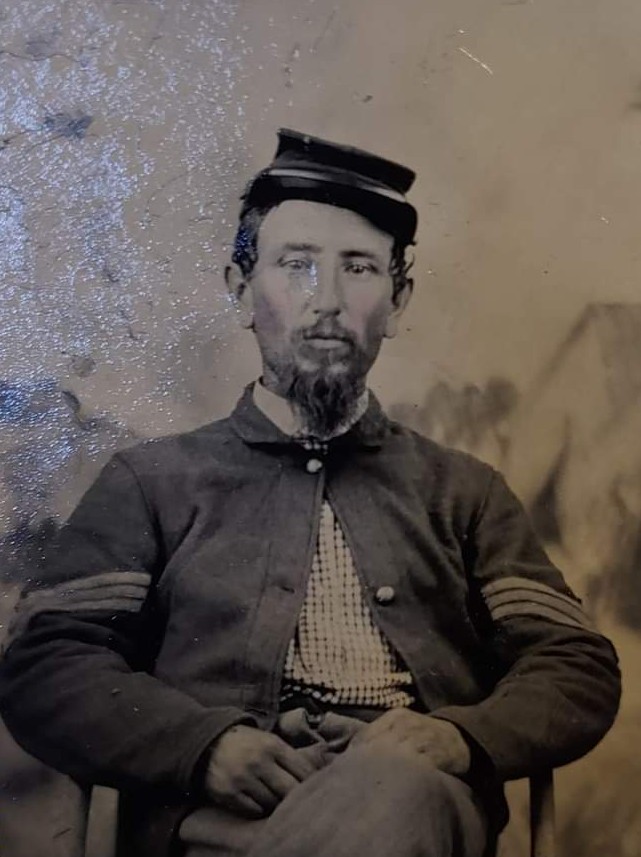

Corporal Daniel B. Sherman of East Greenwich was killed in action May 18, 1864 at Spotsylvania Court House, Virginia (Robert Grandchamp Collection)

Furthermore, the top three regimental officers all had left the Seventh. Colonel Zenas R. Bliss, the West Point educated commander of the Seventh who had trained and disciplined them into an effective fighting force and had earned the Medal of Honor for his heroism at Fredericksburg, was promoted to brigade command shortly before the Seventh left Annapolis. Lieutenant Colonel Job Arnold and Major Thomas F. Tobey, the second and third ranking officers, were both severely ill and received discharges for disability contracted in the service (indeed, in 1869 Arnold died die of the malaria he contracted in Mississippi).

This placed the Seventh in the hands of Captain Theodore Winn of Providence. The commander of Company B, Winn was a seasoned officer who had been wounded at Fredericksburg. The last of the Seventh’s original captains, he was in line to receive the vacant lieutenant colonelcy of the Seventh. A commission was, however, never sent, and he marched out of Annapolis as a captain in command of the officers and men comprising the Seventh.[4]

The Ninth Corps and the Seventh marched south to join the Army of the Potomac, passing in review before President Lincoln before crossing the Potomac River and marching towards Fredericksburg via the old Bull Run battlefield. In the first engagement of Lee and Grant, the Battle of the Wilderness, fought on May 5-6, 1864, the Seventh was lucky; it was held in reserve guarding the supply wagons, only losing four wounded. After the stalemate in the Wilderness, Grant, unlike every other Union commander, did not turn back; instead, he continued to march south towards Richmond.[5]

It was a race now for the critical crossroads of Spotsylvania Court House. Lee won the race and dug in on May 9. The next day, Grant threw a brigade at Lee’s entrenchments in a test of their effectiveness. This single brigade punched through the defenses but did not have enough support and was beaten back with heavy losses. Two days later, on May 12, Grant tried again; this time two entire corps attacked the Confederate entrenchments that had been given the nickname of the “Mule Shoe” due to its inverted U shape.

For nearly twenty hours in the pouring rain, Americans killed each other with muskets, bayonets, tin cups, and their bare hands in the most insane and prolonged fighting of the war, often up close and eyeball-to-eyeball. The Seventh was part of this fighting. As the Ninth New Hampshire ran away, the Seventh, together with the Fifty-First New York, ran forward into the torrential downpour and managed to hold the line until nightfall against a Confederate counterattack. The Seventh lost four dead and twenty-five wounded on May 12. In the after-action report, it was noted of the Seventh, “Great credit is due to the officers and men for their gallantry in undauntedly facing that storm of shot and shell.”[6]

For the next several days both armies remained in their entrenchments, as Union forces tried to find a weakness in the defenses. The Seventh participated in some of these probes, losing five men killed and ten wounded from May 13-17; among the dead was First Lieutenant Darius Cole. On May 18, Grant decided to launch another massive attack to try and overwhelm the overstretched Confederate defenders. The day began very badly for the Seventh before it even got in position. Captain Winn, who had admirably handled the Seventh on May 12, had submitted his resignation before leaving Annapolis. Winn received word that morning his resignation had been accepted and he promptly left the field. Some men now had the gut instinct that only a veteran would possess: it was going to be a bad day for the Seventh Rhode Island.[7]

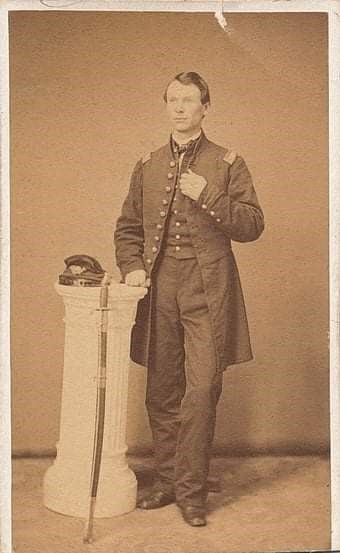

James N. Gladding of Bristol was wounded at Spotsylvania and mortally wounded a few weeks later at Cold Harbor (Robert Grandchamp Collection)

The command of the Seventh passed to twenty-three-year-old Captain Percy Daniels. This would be his first test as a battalion commander. During the training of the Seventh, Daniels was faulted many times for being “immature.” Stephen F. Peckham wrote that Daniels was, “Too young to command himself, much more to command others.” At 3:00 in the morning the Second Division of the Ninth Corps left its entrenchments and started forward. As the Sixth New Hampshire advanced, Captain Lyman Jackman recalled, “we felt that is was almost sure death.” The Seventh was on the extreme right of the Ninth Corps line. The men marched through a swamp, followed by a thick woodlot, and then into dense underbrush. Here the Rhode Islanders witnessed the sight they most feared.[8]

The Seventh had to charge up a hill, lined with infantry, while contending with a battery posted on their flank. At daybreak, the Confederate artillery opened upon the Rhode Islanders. The first few shots flew overhead as Captain Daniels attempted to comprehend the situation around him. The next shot struck the knapsack of Private James Robinson, throwing him to the ground. The third shell fired from a twelve-pound Napoleon cannon landed in the middle of Company H and exploded. Arms and legs flew as six men were hit. Sergeant Samuel E. Rice lost a leg and an arm. As the young man was being carried away, he turned to Company H and said “Boys I can’t be with you anymore, go in.” One officer looking on, recalled the gristly scene in a letter to the Providence Journal, “You would have realized some of the horrors war can bring.” Sergeant Rice died three hours later at a field hospital; his last words were. “Tell them all at home, I die like a man.” The shell also killed two other members of Company H, while severely wounding the other three men.[9]

Using their instinct, the men dropped to the ground to try to escape the fire. Another shell struck the Color Guard, killing Corporal Manuel Open and mortally wounding Corporal Isaac Nye. Corporal Daniel B. Smith, another member of the Color Guard, had his “bowels torn out” by a shell. The men again pulled out bayonets and cups and began scratching into the earth to attempt to build a breastwork. The Seventh was in an exposed position receiving fire from its front and left flanks. The artillery shells continued to rain down upon the Seventh’s position, knocking down tree branches and hot pieces of iron into the thin line. The minie balls whizzed by the entrenching regiment as the men frantically dug in. Sergeant Amos Lillibridge reached for a large rail to throw in front of Company A’s position but was shot through the head. The Confederate defenders now charged the Seventh’s line. Captain Edward T. Allen, a faithful correspondent to both the Narragansett Times and Providence Journal wrote, “Their masses rushed on to our lines only to be driven back with terrible slaughter.”[10]

The surprised Confederates regrouped. Shockingly, Captain Daniels ordered the men to fix bayonets and prepare to assault the Confederate works. One New Hampshire soldier, watching on commented, “It was hopeless to carry the works in the face of a murderous fire.” First Lieutenant Albert A. Bolles was shot through the foot, yielding his company to Sergeant Jonathan Linton. Captain James N. Potter was shot through the leg and left the field. Preparing to give the order to advance, Daniels did not notice a critical threat on his right flank. General Potter had pulled back the rest of his division without notifying Captain Daniels. The firing continued to knock the Rhode Islanders out of their ranks. Private Charles O. Browning suffered a massive wound to the chest. A ball passed through Lieutenant Edward Morse’s face. All along the Seventh’s thin line, Rhode Islanders continued to face a withering fire as they closed ranks and prepared to charge.[11]

Bringing the musket from the shoulder to “port arms;” by placing the rifle directly across the chest, the Seventh went in yelling, “Hurrah.” The firing intensified as the Rhode Islanders pushed on. Sergeant Nathan G. Follansbee recalled, “I saw a number of comrades cut up in an instant.” The unsupported Seventh suddenly was surrounded. Captain Daniels in the heat of the battle became disoriented, unable to issue any command. If the Seventh remained where it was any longer, it would be destroyed. Captain Ethan A. Jenks, commanding Company I, knew what needed to be done. Against Daniels orders, he gave the orders for the Seventh to fall back, thus saving the regiment from annihilation. The Rhode Islanders ran for a series of rifle pits, vacated by a Pennsylvania regiment in their rear; it was the only time in the entire war that the Seventh Rhode Island turned their back on its foe. The charge was costly for the Seventh: the regiment lost ten killed and twenty-one wounded.[12]

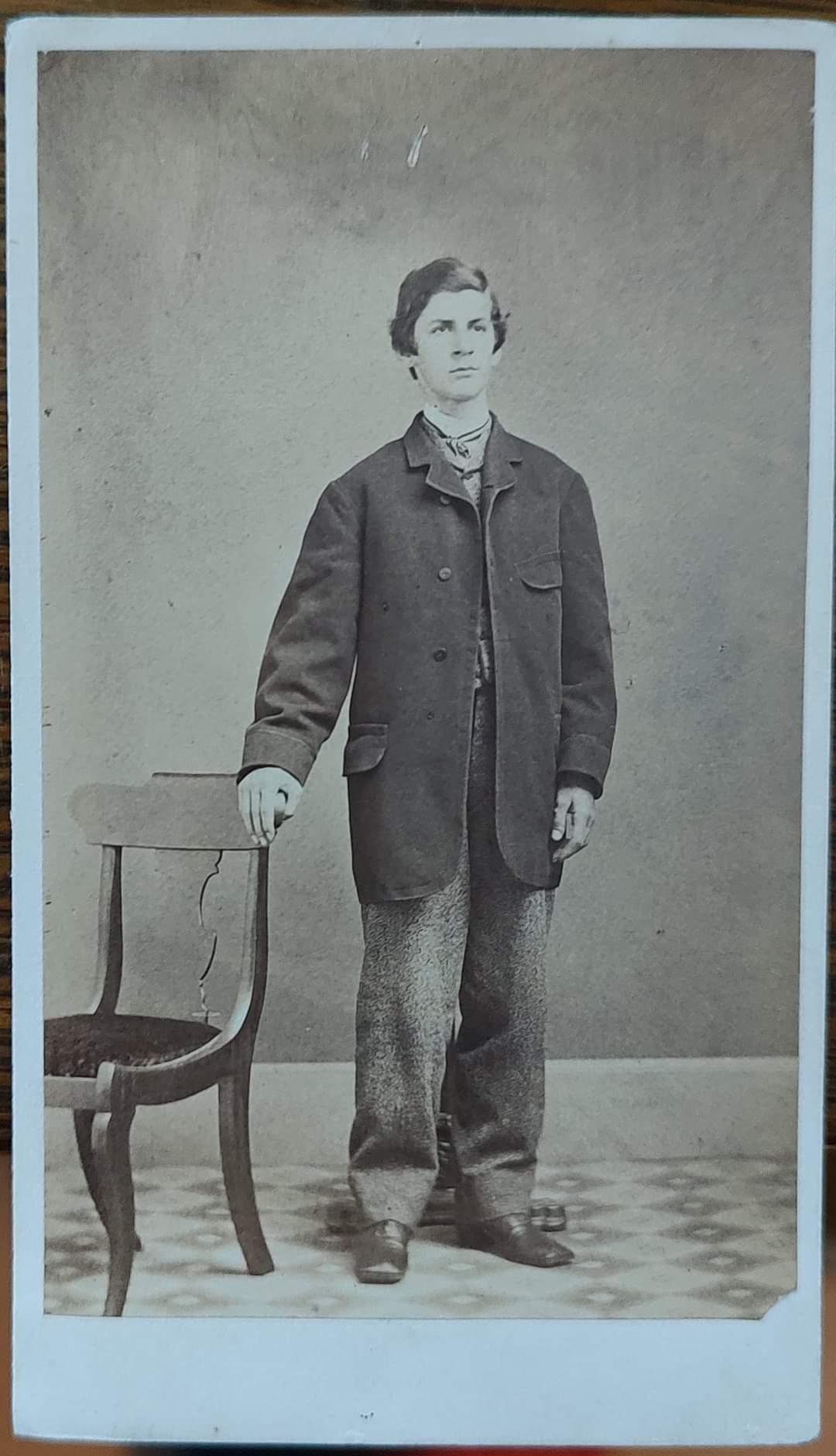

Due to the nature of the Overland Campaign in the spring of 1864 and the tremendous casualties suffered by Rhode Islanders in the six-week ordeal, letters written from the battlefield are extremely rare. However, for posterity we are blessed to have a remarkable letter written by George A. Spencer of Bristol who served in Company I of the Seventh Rhode Island.[13]

A young engraver, Spencer penned two remarkable letters on June 2 and June 4, 1864, the days before and after the Seventh’s costly charge at Bethesda Church, near Cold Harbor. Spencer, who had been captured at Fredericksburg and then exchanged, wrote vividly of his experiences during the war and this author has been fortunate to collect a good number of his letters. Written two days after the events of May 18, 1864, the following letter presents a marvelously descriptive letter of the engagement and gives the best view of the Seventh’s participation on that fatal day.

Camp 7th Regt. R.I.V.

Near Spottsylvania C.H.

May 20th, 1864

Dear Parents

I am well and hope these few lines will find you the same. We moved from the center of our lines to the left last night and here we are throwing up breastworks. One more was wounded in our Co. named William.[14] We have no officers that know anything on our Regt. now.[15] 3 of them skedaddled yesterday, and the one that had command of us led us right up to the Rebel Battery so we could see them work their guns and kept us there 3 or 4 hours, and they was firing grape and canister and solid shot at us all the time.[16] They cut trees down that was 8 inches thick just like straws. I tell you we hugged the ground pretty close, and every man that raised his head a foot got a bullet through it from the Rebel Sharp Shooters. If we had stayed there 20 minutes longer there would not been any 7th R.I. They almost surrounded us when we had the order to fall back and the way they poured grape and canister into us when we left was a caution. I cant tell how fast we fell back but twas not slow. Clarke Whitford’s gun was struck by a shell and bent it up like a hoop.[17] The same shot killed a sergeant and 3 men in Co. H.[18], the 6th Corps lays right side of us. I went over to the 2nd today[19] and see Henry and Geo. Bush.[20] They was all right. Allen Monroe got wounded in the hand[21] and so did George Engram.[22] Henry[23] got 2 letters from you today and so did I. I got Ella’s picture too and 50 cents. We cant buy anything to eat here because there is no sutlers allowed here. So you see money is of no account. I will send you $5.00 in Confederate money. I and some of our men took it out of a dead Rebel’s pocket. James Phelps[24] is all right and he says he is as taught as a boiler and so is Ezra Sherman.[25] He got a letter from home today. 30 Rebels just came into our lines and gave themselves up. Send me some paper so I can see how the Battle goes on. I don’t think we have drove Lee 3 inches. I think we got the worst of it yesterday. The Irish Brigade took one line of their breastworks but they got drive out again. Our lines are in the shape of a horseshoe. What do they think of it at home? Our Regt is mostly played out, only 180 muskets. Our Co. is the biggest one in the Regt. Co. H has got only 2 men and 2 sergeants. Allen Pierce[26] run every time we went in, but you need not say anything to anybody. If you show this letter to anybody, scratch out these few lines. It is so dark I can’t see to write any more so good bye. Write as soon as you get this. From your son,

Geo. A. Spencer

Co. I, 7th Regt. R.I.V.

Washington D.C.

Private George A. Spencer survived the Civil War and returned to Bristol where he married and started a family. Like many veterans of nearly every war, he put his soldiering days behind him and was never an active member of any veteran organization. He died on September 19, 1914. Fortunately for posterity, many of his letters survive.[27]

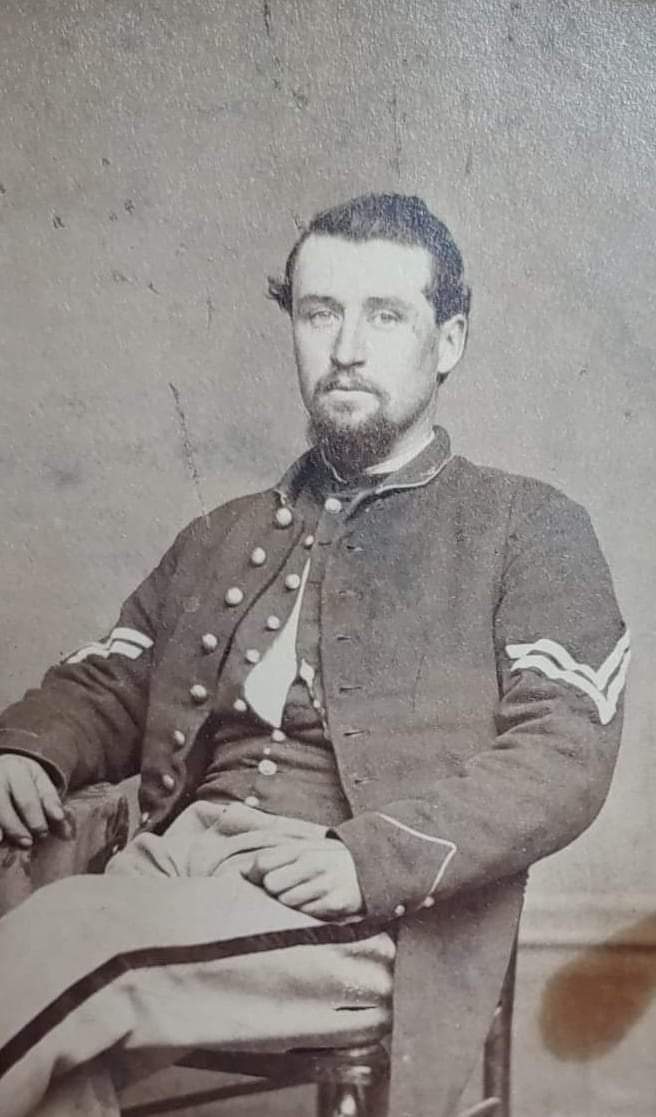

First Sergeant Jeremiah P. Bezeley of Company B was shot in the head at Cold Harbor and lived (Robert Grandchamp Collection)

Notes

[1] For the two best accounts of this battle, both of which were consulted heavily for this article refer to Gordon C. Rhea, The Battles for Spotsylvania Court House and the Road to Yellow Tavern, May 7-12, 1864 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1997) and Gordon C. Rhea, To the North Anna River: Grant and Lee May 13-26, 1864 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000). [2] This thumbnail sketch of the Seventh is taken from William P. Hopkins, The Seventh Regiment Rhode Island Volunteers in the Civil War: 1862-1865 (Providence: Snow & Farnum, 1903). [3] Augustus Woodbury, Major General Ambrose E. Burnside and the Ninth Army Corps: A Narrative of Campaigns in North Carolina, Maryland, Virginia, Ohio, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Tennessee, During the War for the Preservation of the Republic (Providence: Sydney S. Rider, 1867), 365-370. Emor Young to Martha Young, March 23, April 13, and April 16, 1864, Robert Grandchamp Collection. George A. Spencer to Parents, June 12, 1864, Robert Grandchamp Collection. [4] Zenas R. Bliss, The Reminiscences of Major General Zenas R. Bliss, 1854-1876: From Texas Frontier to the Civil War and Back Again (Austin: Texas State historical Association, 2007), 357-361. Meredith Dyer Sweet, “The Journal of Anna Maria (Angell) Arnold, 1867-1869,” Rhode Island Roots, Vol. 44, No. 2(June 2018), 58-86. [5] For the opening chapter of the Overland Campaign, refer to Gordon C. Rhea, The Battle of the Wilderness: May 5-6, 1864 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1994). [6] Rhea, Spotsylvania Court House, 232-260; Seventh Rhode Island Volunteers, Descriptive Book and Letter Book, Rhode Island State Archives. [7] Rhea, To the North Anna River, 131-163. Court Martial of Alfred M. Channell, Records Group 153, National Archives, Washington, DC; Seventh Rhode Island Descriptive Book. [8] Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 174-75; Lyman Jackman, History of the Sixth New Hampshire Regiment in the War for the Union (Concord, NH: Republican Press Association, 1891), 250-252; Stephen F. Peckham, “Recollections of a Hospital Steward in the Civil War,” Newport Historical Society. [9] Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 174-276 and 407-408. Providence Daily Journal, June 20, 1864; Providence Evening Press, June 13, 1864. [10] Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 291-94. Providence Daily Journal, June 20, 1864; The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Vol. 36, 927-392. [11] Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 174-176; Edward O. Lord, History of the Ninth New Hampshire Volunteers in the War of the Rebellion (Concord: Republican Press Association, 1895), 364-366. [12] Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 174-176. William O. Harrington, Diary, May 18, 1864, North Scituate Public Library, Scituate, RI; Peckham, “Recollections.” Seventh Rhode Island Descriptive Book. [13] See Robert Grandchamp, “Two Letters from Bethesda Church,” Rhode Island Roots, Vol. 44, No. 4 (December 2018), 213-223. [14] No casualties were recorded for a Company I soldier named “William.” Seventh Rhode Island Descriptive Book. [15] Despite his misgivings against the officers in the Seventh, three Seventh officers, Captains Ethan A. Jenks, Peleg E. Peckham, and William H. Joyce received rare brevet promotions to major for their heroism on May 18, 1864. Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 346-349 and 351. [16] Percy Daniels led the Seventh into action on May 18, 1864. Despite his failure that day, due to his family’s connections in Rhode Island, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel and led the Seventh for the rest of the war, largely hated by the officers and men of the Seventh. He later moved to Kansas and served a term there as lieutenant governor. Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 322-325. [17] Clark Whitford was a forty-year-old shoemaker from Bristol when he enlisted in the Seventh on August 16, 1862. He was wounded at Fredericksburg and May 18, 1864, at Spotsylvania. He survived to muster out on June 9, 1865. After the war he was an active member of the Babbitt Post # 15 of the Grand Army of the Republic. Seventh Rhode Island Descriptive Book. Post Records, Babbitt Post # 15, Bristol Historical Society, Bristol, RI. [18] The sergeant killed from Company H was Samuel E. Rice of East Greenwich; he had served in the Kentish Guards since he was twelve years old. Also killed by this shell was Private Richard Gorton of North Kingstown and Private John E. Rice of Warwick. All three men were buried at Fredericksburg National Cemetery in Virginia. Seventh Rhode Island Descriptive Book. Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 407-408. [19] The Second Rhode Island, Company G of which had been recruited in Bristol. The Second Rhode Island served as part of the Sixth Corps. [20] Private George A. Bush of Bristol served in Company G of the Second Rhode Island with brother Sergeant Henry F. Bush. Henry had been wounded at the Wilderness May 5, 1864, and died of disease contracted in the service on September 15, 1866. Elisha Dyer, Annual Report of the Adjutant General of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations for the Year 1865 (Cor., Rev., and Republished), Volume I (Providence: E.L. Freeman & Son, 1893), 96. [21] Allen M. Munroe of Bristol served in Company G of the Second Rhode Island Volunteers. He was “wounded slightly” May 12, 1864, at Spotsylvania. Munroe survived to muster out on July 13, 1865. Dyer, Annual Report, Volume I, 174. [22] Private George S. Ingraham served in Company G of the Second Rhode Island Volunteers; he was from Bristol. He was shot May 10, 1864, and was mustered out June 17, 1864. Dyer, Annual Report, Volume I, 144. [23] Henry Gladding was the best friend of George A. Spencer. He was from Bristol and was an eighteen-year-old single laborer when he enlisted into the Seventh on August 16, 1862. He was slightly wounded at Fredericksburg and on May 12, 1864, at Spotsylvania. He was mortally wounded June 3, 1864, at Bethesda Church. Sent to a hospital in Washington, he died on July 3, 1864, of his wounds; his body was returned to Bristol for burial. Seventh Rhode Island Descriptive Book. [24] James T. Phelps was a fellow jeweler from Bristol who served in Company I of the Seventh; he was twenty-one and single when he joined up on August 15, 1864. A good soldier, he was continuously promoted through the ranks to sergeant and eventually to first lieutenant of Company I, serving as company commander during 1865. He was mustered out on June 9, 1865, and returned to Bristol where he was active in Babbitt Post. Seventh Rhode Island Descriptive Book. Hopkins, Seventh Rhode Island, 365. Babbitt Post Records. [25] When Ezra Sherman enlisted into the Seventh on August 19, 1862, he stated he was nineteen years old, single, and a farmer. He was wounded at Fredericksburg, June 3, 1864, at Bethesda Church, and was shot in the chest June 17, 1864, at Petersburg. Despite these wounds he returned home to Bristol in June 1865. Seventh Rhode Island Descriptive Book. [26] Allen Pierce of Company I, Seventh Rhode Island Volunteers was a married laborer from Bristol who was nineteen when he enlisted on August 20, 1862. He was mortally wounded on the morning of June 6, 1864, and died later that day. He is interred at Yorktown National Cemetery, Grave 424. Seventh Rhode Island Descriptive Book. [27] George A. Spencer Death Certificate, September 19, 1914, Bristol Town Hall, Bristol, RI. Papers of the Seventh Rhode Island Veteran Association, Robert Grandchamp Collection.