Rhode Islanders are, or should be, familiar with George Washington’s famed letter of August 21, 1790 to the Friends of Touro Synagogue in Newport and that public missive’s ringing declaration “to bigotry no sanction to persecution no assistance.” Lesser known is the fact that Washington was repeating and reaffirming the phrase formulated by Moses Seixas, a prominent leader of the Touro Synagogue, in an earlier letter of August 17th given to the nation’s new chief executive by the Jewish congregation in Newport during Washington’s triumphal visit to that town in mid-August 1790. Washington visited Newport after Rhode Island belatedly joined the Union—it was the last of the original thirteen colonies to adopt the U.S. Constitution.

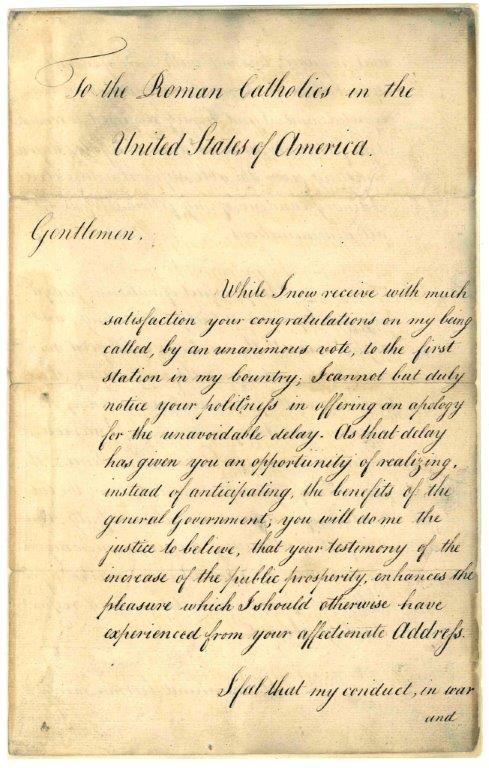

Lesser known still (in predominantly Catholic Rhode Island) is Washington’s letter of hope to America’s tiny Catholic minority written on March 12, 1790, five months prior to the new president’s delayed visit to recalcitrant Rhode Island.

In the aftermath of Washington’s unanimous selection by the Electoral College on February 4, 1789, as the country’s first elected president under the new U.S. Constitution, America’s first Roman Catholic bishop, John Carroll of Baltimore joined with his brother Daniel, constitutional convention delegate and Maryland’s first congressman; his cousin Charles of Carrollton, a Maryland signer of the Declaration of Independence; Thomas Fitzsimmons of Philadelphia, another Signer; and Galway-born Dominick Lynch, a prominent merchant-philanthropist and the founder of Rome, New York, to send a letter of congratulation to America’s new chief executive. This address, after expressing the “joy” of American Catholics upon Washington’s election, expressed the following hope: “While our country preserves her freedom and independence, we [Catholics] shall have a well-founded title to claim her justice—the equal rights of citizenship . . . . We pray for the preservation of them where they have been granted and expect their full extension from the justice of those states which still restrict them.”

The Rhode Island General Assembly had denied voting rights to Catholics (and Jews) in 1719. Whatever anti-Catholicism existed in Rhode Island was mollified by the assistance rendered to the struggling Americans during the Revolutionary War by Catholic France and by the presence of large numbers of French troops under General Comte de Rochambeau who arrived in Newport in July 1780 and who played a key role in defeating a British army at Yorktown, Virginia, in September 1781, which led to America’s victory in the war and securing its independence. Indeed, some of the French soldiers remained behind in Rhode Island. In February 1783, the General Assembly removed the voting ban against Roman Catholics by giving members of that religion “all the rights and privileges of the Protestant citizens of this state.” Three states, however, continued to discriminate against Catholics when Carroll and his associates wrote their letter, and several more, including Rhode Island, continued to withheld the vote from those of the Jewish faith.

President Washington’s reply to the five-person Catholic contingent came on March 12, 1790. It acknowledged the claims of Catholic citizens to equality and added, “I hope to see America among the foremost nations in examples of justice and liberality.” He could have also alluded to Article VI, Section 3 of the new Constitution whereby “no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States.”

The cover page of the March 12, 1790 letter to Catholics written by President George Washington. The letter is housed in the archives of the Archdiocese of Baltimore.

Bishop Carroll and President Washington maintained a cordial relationship until Washington’s death in December, 1799. During the last summer of Washington’s life, he entertained the bishop and his niece, Elizabeth Carroll, at Mount Vernon. Carroll’s eulogy for the departed Washington was moving, eloquent, and sincere.

Just as those of the Jewish faith annually celebrate George Washington’s letter to the Hebrew congregation of Newport’s Touro Synagogue (an event at which I was privileged to speak in 1976), so also should Catholics acknowledge and celebrate Washington’s letter of March 12, 1790 “To the Roman Catholics in the United States of America.” Both documents are milestones along America’s rocky road toward complete freedom of belief—an achievement that is our greatest contribution to world civilization. Roger Williams, its early advocate, aptly described it as “Soul Liberty.”

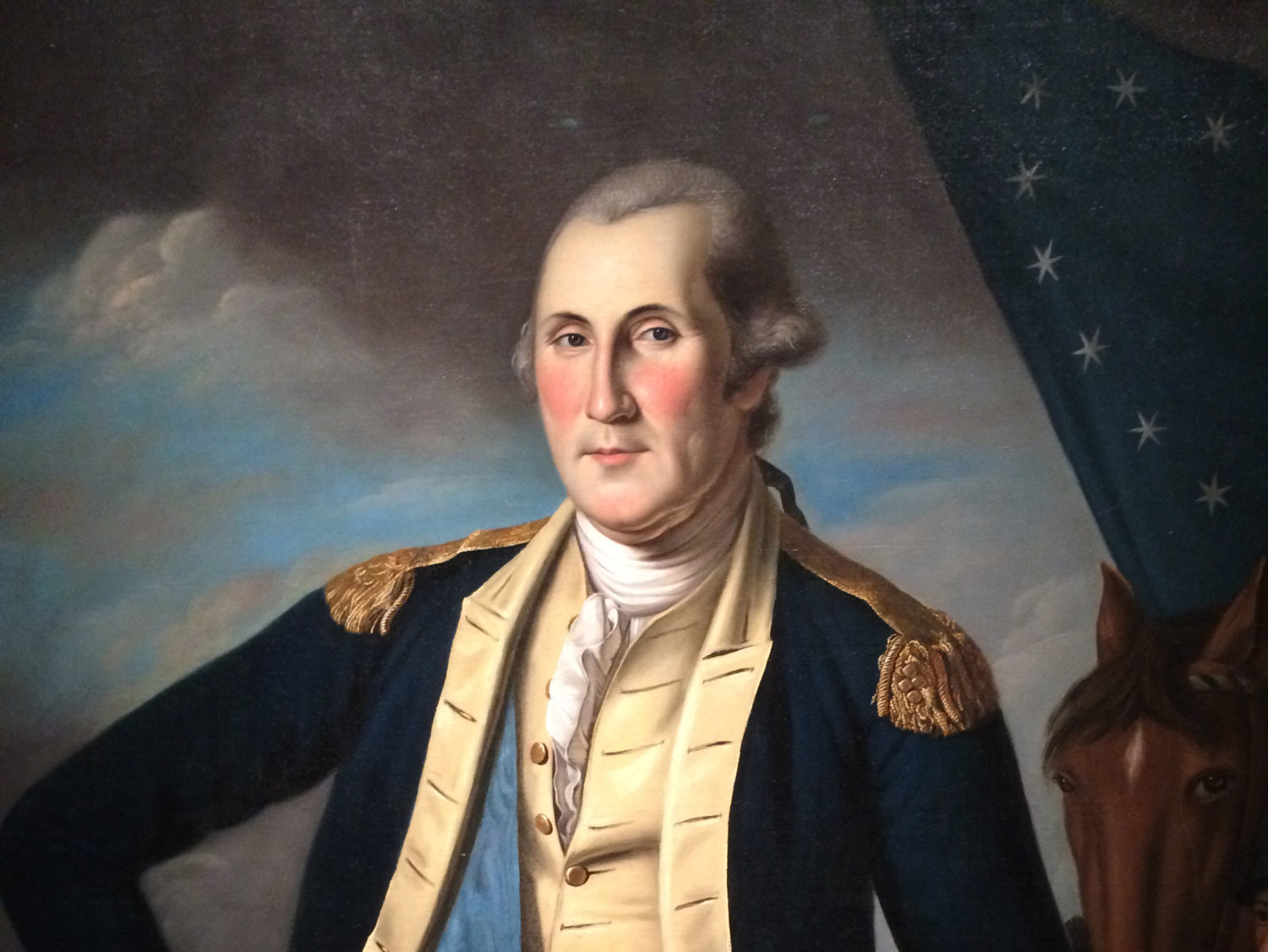

[Banner image: George Washington on the field at the Battle of Yorktown, portrait by Charles Wilson Peale, ca. 1780-1782 (National Portrait Gallery)]