Despite its familiarity to students of Rhode Island history as the site of one of this country’s early nineteenth century race riots, occurring the night of October 17-18, 1824, the location of the Providence neighborhood known as Hardscrabble has been lost for almost a century. As we approach the two hundredth anniversary of this regrettable incident, this article establishes Hardscrabble’s location, provides some context for its development, and the fate of some of its early inhabitants.

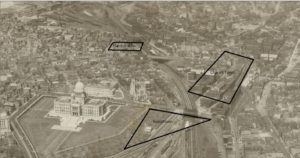

It is fairly common knowledge the summit where Rhode Island’s State House stands is called Smith Hill. The name was acquired from china merchant Henry Smith whose grand home once crowned the hill across from the State House site.[1]

Prior to Smith’s construction the hill was known as Camp Hill. Zachariah Allen, who also had a home on the hill, attributed the name to its use as a campsite by Native Americans during their visits to Providence.[2] It was also used for that purpose by various military and militia companies into the early nineteenth century.[3] Rising to about seventy feet above the north shore of Providence’s Great Salt Cove (called here, the Cove), Camp Hill was home to one of the earliest expansions of Providence. It was also home to three of Providence’s more reviled communities, Charlestown, Snowtown, and Hardscrabble.

Location of Snow Town, Charles Town, and Hardscrabble on Camp (Smith) Hill (Detail from VM18_031 Providence Public Library)

Edward Peckham’s watercolor of the Cove showing the south slope of Camp Hill (Providence Public Library)

Initially settled on the east side of the Moshasuck and Great Salt rivers, Providence’s first mill was also constructed on the east side of the Moshasuck River at the foot of Stamper’s Hill (it was a stamping mill).[4] Following the destruction of the original mill during King Philip’s War, a new mill was constructed on the west- side of the river, opposite the original mill’s location. The presence of the mill at the foot of Camp Hill’s gentle eastern slope and the crossing provided just north of the mill pond at Stephen’s Bridge, promoted the early and dense development of that portion of Providence.[5] In 1738 another bridge was constructed below the mill, providing a more convenient connection to the lower Towne Street (now North Main Street).[6] By the time of the American Revolution, the community on the west side of the river, now called Charles Town had a reputation as a busy and bawdy place: “…our company went over the bridge, got a Negro fiddler, and proceeding up town went into a house to have a dance, but a woman was sick there, so we went along further over the mill bridge and went in a house to make our frolic there,…”[7]

The typical soil erosion pattern on hillsides is for the topsoil on the steeper slopes to wash away, exposing a sandy subsoil, eventually cut by gullies and ravines.[8] The path of the Towne Street up Constitution Hill is adjacent to a ravine cut into that hill’s western slope.[9] This pattern of erosion occurred on all the hills surrounding Providence’s upper cove, so that throughout its early history, the town was framed on three sides by the sandy flanks of Federal, College and Camp Hills. The filling in of the Cove and modern landscaping practices have done much to hide this element of Providence’s early setting.

The south slope of Camp Hill above the Cove was settled early. Thomas Clemence had a house by the Rumley Marsh meadow just above the mouth of the Moshasuck. His neighbor John Scott had a house by Whipple’s Island, also called the Little Island.[10] Redevelopment of the south slope after King Philip’s War was limited. During the second half of the eighteenth century as the population and commerce migrated south toward what became Market Square and west to Weybosset, the south slope of Camp Hill became even more remote from the activities of the town. It was considered so isolated, during the American Revolution town officials proposed to locate a smallpox hospital in Fourstack Meadow, west of Great Point.[11] When the owners of the meadow objected, the town chose to lease properties in North Providence for the hospital.[12] John Fitch’s 1790 sketch of Providence shows nothing of interest on the west side of the river below Charles Town, despite a shipyard being located at the foot of Broad Lane (now Smith Street.”)[13]

The 1798 Construction of another bridge across the Moshasuck was a harbinger of change. The new link, located south of the Mill Bridge, connected Broad Lane to North Main Street. Lots on the south slope of Camp Hill were platted and marketed as being “near the new Bridge …. and on the adjacent Hill and Plain which for situation and prospect are perhaps exceeded by none in the Vicinity of the Town.”[14]

Shortly thereafter, Henry Smith began construction on his landmark home above the Cove. At about this time house-wright Josiah Snow also began to build on Camp Hill. Following his death in 1802, his son, Josiah continued the business. Other Snows took over in 1813 when Josiah 2d died. The Snows often built small houses for financially strapped clients on less desirable lots.

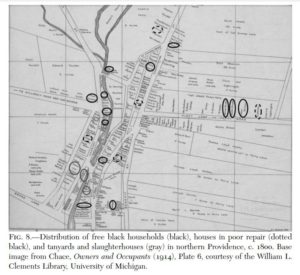

When Peter Randall, a substantial land owner and farmer died in 1808, one of the properties he left to his son, Daniel, a cordwainer (a maker of new shoes from new leather), was a six acre lot at the north end of Camp Hill. Overlooking the old compact part of town and Steven’s Bridge, the lot extended west from Black Street to the crest of the hill, and north from the Killingly Road (now Orms Street) to the Road to Stampers (renamed Martin Street in 1806, and now called Chalkstone Avenue). Henry Chace’s map of 1798 Providence denotes the lot as “mostly sand hill.”[15]

Figure 8, from Kate Silbert’s Needle Pen and the Social Geography of Taste in Early National Providence. Maps the presence of free Black households on Constitution Hill and across the Moshasuck River in Charles Town. Peter Randall’s Six Acre Lot where Hardscrabble would develop is at Upper Left.

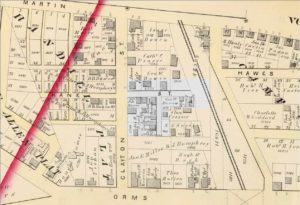

At the end of 1814 the Supreme Judicial Court had found Daniel Randall to be not competent to manage his own affairs. His cousin, Dexter Randall was appointed guardian of Daniel’s estate with authorization to settle his debts.[16] Dexter Randall had the six acre lot platted, laid out a cross street (Clayton Street) connecting Orms and Martin Streets, and in May of 1815 sold the lots at auction.[17] One of the many purchasers was Nehemiah Sheldon of Providence, who bought eight of the lots for a total of $96.00.[18]

In 1818, Sheldon sold six of these lots for $200 to Benjamin Addison.[19] Addison, another cordwainer, owned various small lots on Bark Street, North Main Street and Olney Street.[20] Addison laid out a twenty foot gangway (Kane Street) running west to east between Clayton and Black Streets and a twenty foot wide stub of a road (May Street) off the south side of Kane Street.[21]

Detail from G. M. Hopkins, 1875 Atlas of Providence, Volume 1, Plate B, showing Benjamin Addison’s purchase from the Daniel Randall Plat.

The crest of Camp Hill lay between Broad Lane and Orms Street. From there, it descended northward to Martin Street, where it dropped precipitously into the swamp below.[22] The downward slope of the hill just north of Orms Street was fairly steep, easing in the vicinity of Kane Street. As a result, both Kane Street and May Street were at a much lower elevation than Orms Street. At the south edge of Addison’s property, May Street was almost twenty feet below the level of Orms Street. The steep slopes to the west and south formed the walls of what came to be called Addison’s Hollow.[23]

Within days of his initial purchase, Addison sold all his lots on the north side of Kane Street to Providence grocer Sylvanus G. Martin.[24] In May of 1819 Addison sold a small lot at the south corner of Kane Street and Black Street to painter Peter Keech.[25] That July, the lot at the east corner of Kane and May Streets went to John Daniels, a Black mariner.[26] Later that month, Thomas Read, a Black barber, purchased the three lots between Daniels and the foot of May Street.[27] William J. Brown, in his autobiography, refers to Thomas Read as the upper crust of Providence’s colored population.[28]

Though Daniels and Read were among the first Black residents of what would come to be known as Hardscrabble, they were not the first Black residents on this section of Camp Hill. In 1808 George M’Carty had purchased a home on Orms Street, west of Black Street that had been previously owned by the Snow family.[29] In 1816 M’Carty’s former property was sold to a Black laborer by the name of Christopher Hall.[30]

In 1813, Isaac Bowen, a Black laborer, had purchased a house and lot on the south side of Martin Street.[31] Situated between Black Street and Clayton Street, his “small red house” was referenced as a Martin Street landmark for many years. There appears to have been some relationship between Bowen and merchant Henry Smith. In 1815, when Dexter Randall auctioned Daniel Randall’s acreage, Henry Smith, acting as agent for Bowen purchased the lot abutting the west side of Bowen’s property.[32] In 1816 a Black hairdresser named John L. Jones purchased the lot on Martin Street to the west of Bowen at the east corner of Clayton Street.[33]

The 1820 U.S. Census indicated that Hardscrabble and Addison’ Hollow were still mostly unsettled at that time. On sheet 134, Isaac Bowen, whose home was on Martin Street is listed, followed by the names of three Black men and a white man (in order of appearance, Peter Greene, Joseph Daniels, John Daniels, and John S. Addison). John S. Addison’s name is followed by that of Christopher Hall.[34]

Addison subdivided his lots on the west side of May Street into small 25 x 50 foot lots which he sold for fifty dollars apiece. In July of 1820 the lot at the foot of May Street was sold to Prince Congdon, a Black laborer.[35] The 1820 Census indicates that Congdon had been living in a tenement of Simeon Wheeler’s on one of the waterside gangways opposite the Old State House on North Main Street. That neighborhood, in the shadow of William and Joseph Russell’s stately North Main Street home, hosted a number of poor Black and white families. It also hosted the jail.[36]

Detail from a lithograph (circa 1825) showing Providence from the north shore of the Cove. Prince Congdon’s former neighborhood on the east side of the Cove is at left. The Russell House (still extent on North Main Street) is directly in line with the Baptist Church. (Etat de Rhode Island, Deroy, Isidore L., after Milbert, Yale Art Gallery)

In December of 1820, Jeremiah Rounds purchased the small lot on May Street north of Congdon’s. Rounds, a white mason who resided on Plane Street on the Weybosset side is unlikely to have ever lived in Addison’s Hollow.[37]

At some point, John L. Jones began operating his Martin Street house as a dance hall.[38] Although it was not located in Hardscrabble, its proximity to that neighborhood appears to have altered the public perception of that isolated section of northwest Providence. Residents of Hardscrabble undoubtedly frequented Jones’ dance hall. Residents of Snowtown would have passed Addison’s Hollow and Hardscrabble on their way to Jones’s hall.[39]

In February of 1821, John Thompson, a Black mariner who had been living in a tenement of Philip W. Martin’s in the mixed-race community on Stevens and Hewes streets, purchased the small lot on May Street north of Jeremiah Rounds.[40] He was still living in the Stevens Street/Hewes Street community when called before the Town Council late in 1823.[41]

Financial issues appear to have caused Thomas Read to leave Addison’s Hollow in the spring of 1821.[42] His three lots on May Street were sold to Nicholas Ferguson, a Black mariner from Boston.[43] Read took up residence in the former Red Lion bawdy house on Power Street and set about rehabilitating its reputation.[44]

In December of 1822 John L. Jones was convicted of operating a disorderly house, and sent to prison.[45]

The demise of Jones’s dance hall was an opportunity for Prince Congdon. He mortgaged his lot at the foot of May Street, purchased another of Addison’s lots on the north side of John Thompson’s land, and began to operate his original property as a dance hall.[46] The dance hall does not, however, appear to have been a successful venture. Congdon defaulted on the mortgage and Addison received the property back; in September of 1823, Addison sold the dance hall and lot to a grocer, John S. Parks.[47] The dance hall continued to change owners until August of 1824 when Parks sold it to Henry Wheeler, a Black laborer.[48]

In 1823, Jeremiah Rounds sold his May Street property north of the dance hall to Jesse B. Sweet.[49] Sweet, a grocer who lived on Smith Street, is unlikely to have ever lived in the Hollow.[50]

In March of 1824, John Thompson appeared before the Providence Town Council to complain that the body of his daughter had been stolen from the vault of Dr. Stephen Randall. Although the Council resolved to prosecute the perpetrator, there does not appear to be any record of further action on Thompson’s complaint.[51]

In the Providence Town Council’s 1822 census of Black housekeepers, Benjamin Addison is listed as the owner of three properties having Black tenants. None of the occupants of these properties can be positively identified as being residents of Hardscrabble in 1824. Joseph Daniels, Prince Congdon and Nancy Carr are also included in the census of Black housekeepers, as are John L. Jones and Eliza Hall. Jones and Hall are recorded as tenanting “Jones’ hall”.

Shockingly, by today’s standards, the 1824 Providence Directory did not include any Blacks in its listing of Providence residents. The Directory’s List of Streets includes Black Street, but no one is listed as residing on that Street. Clayton and May Streets are not included in the 1824 Directory’s List of Streets.

At the time of the mob action in October of 1824, Henry Wheeler owned the southernmost (dance hall) lot on the west side of May Street in Addison’s Hollow. Jesse B. Sweet owned the lot next north. John Thompson’s lot was next above Sweet, and Prince Congdon above Thompson. Benjamin Addison retained ownership of the lot at the head of May Street on the west side. John Daniels owned the large lot at the head of May Street on the east side, which he shared with his brother Joseph. Boston Mariner, Nicholas Ferguson owned the remaining three lots on the east side of May Street. Christopher Hall’s home was high above Addison’s Hollow on Orms Street, almost 100 feet from the foot of May Street.

The Hard-Scrabble Calendar is a summary of the trial of the men indicted for rioting in Addison’s Hollow. Published in 1824, it states in its Introduction that in October of 1824 there were approximately twenty houses in Hardscrabble. Testimony in the Calendar indicates seven houses in the Hollow were pulled down and three or four others damaged.[52] The method of destruction appears to have been to demolish the chimney to below the roof line, cut the wall posts and studs, and then overturn the house.[53]

Wheeler, Congdon, Thompson and John Daniels remained in Addison’s Hollow after the riot.[54] Wheeler appears to have defaulted on his mortgage for the dance hall. Over the next two years ownership of the hall changed hands a number of times. Wheeler may have continued to reside there until the following incident occurred:

Providence, Monday, Feb. 20. FIRE. Yesterday morning between one and two o’clock, a fire broke out in one of the clump of wooden houses and hovels in the North Suburbs of the town, just over the line, celebrated in the annals of our courts and in common parlance as the city of Hardscrabble; inhabited by blacks. Immense numbers of our citizens repaired to the spot, but it seemed, to amuse themselves with the bonfire rather than to aid in preventing the loss of the property, which though of trifling value, and too often used for vile purposes, was nevertheless of as much comparative consequence to the wretched inhabitants it served to shelter, as the more costly edifices of the wealthy are to their comfortable occupants. Several of our fire wards exerted themselves for some time to effect a concert among the people but from the difficulty of getting water, and the indisposition of the populace, who were probably afraid of exposing themselves to the influenza by hard work, it was in vain, and the fire was suffered to riot undisturbed. In the end however, but one private house, the largest in the city, and a publick building adjoining, much celebrated as the Dancing Hall, were consumed. This last, nothing but fire could have purged of its impurities, and even this element seemed to dread the contest, and for a long time it stood unharmed in the midst of the surrounding flame. Sufficient of the building having been torn down to give free circulation to the air, the fire so encouraged was induced to take possession.[55]

In November of 1826 Prince Congdon sold the western half of his small lot to Wheeler.[56] The 1875 Hopkins Atlas of Providence shows a building still in place on the back half of Congdon’s lot. In 1828 Congdon mortgaged his property to Benjamin P. Wilbour. In 1829 Wilbour took ownership of the property.[57] The 1838 Providence Directory lists Congdon as a Labourer, residing on Point Street.

In 1828 John Daniels bought the dance hall lot from Attorney Charles Tillinghast.[58] Tillinghast had obtained it as the result of a court ordered sale for a debt owed by John S. Parks.[59] Daniels is listed in the Providence Directory for each of 1832, 1836 and 1838 as a “Labourer” residing at the rear of Black Street. The 1844 Directory does not include his name.[60]

In 1825 John Thompson purchased the lot (Sweets) between his and the Dance Hall lot.[61] Over the next fourteen years he continued to purchase abutting properties. The 1832 Providence Directory lists him as a Drayman, residing in the rear of Black Street. The 1836 Directory lists the same occupation but has changed his residence to in the “rear of Martin Street,” as does the 1838 Directory.[62] By 1839 Thompson owned most of the block between Clayton and May Streets, and in 1842 he sold his Hardscrabble holdings and moved to Federal Hill.[63]

The origin of the name Hardscrabble is obscure. Prior to the riot in October of 1824, the name does not appear in any of the recorded transfers of property. Deeds for properties in Daniel Randall’s lot are uniformly referred to as being part of the Camp Hill Lot. The 1824 Providence Directory makes no mention of Hardscrabble. It also makes no mention of Providence’s Black inhabitants. The name may have originated with the local newspapers as part of an effort to label the community as unworthy in their campaign against the neighborhood’s perceived immorality.

Benjamin Addison died in 1826.[64] Newspaper advertisements for the sale of his estate specifically mention two of his properties as being located in Hardscrabble.[65] The deeds for those sales also utilize the name.[66] The 1836 Providence Directory has an entry for Hardscrabble in its Listing of Streets. It is described as a small collection of houses south of Martin Street. Eleven heads of household were listed as being resident at that time, ten of whom were colored (the term is the Directory’s). The 1844 Directory has a similar listing, but the community had grown to thirty-two heads of household, of whom twenty-eight were colored. The 1850 Directory does not have a listing for Hardscrabble and it no longer distinguishes between white and Black residents.

In 1847 Providence exercised an early form of urban renewal when the Providence and Worcester Railroad was allowed to cut a swath through Snowtown, Charlestown and Hardscrabble. All three neighborhoods survived this effort to some extent.

Addison’s Hollow, shortened to “the Hollow,” remained in the police and newspaper lexicon for the remainder of the nineteenth century:

A Descent Upon the Hollow. – The Mayor, with a posse of the police, made a descent upon the “Hollow,” Friday night, and arrested near forty of both sexes and all colors. The affair was well planned and well conducted, and no serious resistance was made. The persons arrested were brought before the Court of Magistrates, and the cases committed, and some were discharged. “The Hollow” is one of the most infamous places, not only in Providence, but in any city in the land. Every crime, from petty larceny to murder, has been committed there, and no one knows the undetected wickedness that is constantly going on in that locality. Nearly the whole of the time devoted to criminal cases, at the present term of the Supreme Court, was occupied in the trial of persons indicted for crimes committed in the Hollow – crimes of which a great portion, under the law as it existed a few years since, would have been capital.[67]

In 1876, Providence constructed a police station near the foot of Martin Street (renamed Chalkstone Avenue) presumably to help tame the neighborhood.[68]

Detail from the H.F. Walling 1857 Map of Providence showing the path of the Providence and Worcester Railroad through Hardscrabble

By the end of the American Civil War the Irish began to establish a presence on May Street.[69] They in turn were supplanted in the 1880’s and 1890’s by a substantial population of eastern European Jews.[70] At about that time, the city attempted to re-brand that neighborhood and a number of others across the city. Clayton Street was renamed Shawmut Street in 1894.[71] The neighborhood remained a predominant Jewish enclave until it was it was demolished for the construction of Interstate 95 in 1964.

Overlay of Clayton, Kane and May Streets from the G. M. Hopkins, 1875 Atlas of Providence, on top of a current aerial photograph of Orms Street and I-95

Endnotes:

- Smith Hill, Providence, Statewide Historical Preservation Report P-P-4 (Rhode Island Historical Preservation Commission, 1980), 6.

- Allen, Zachariah, Defence of the Rhode Island System of Treatment of the Indians, and of Civil and Religious Liberty (Providence Press Co., 1876), 11.

- Smith Hill, Providence, Statewide Historical Preservation Report, 6.

- Allen, Defence of the Rhode Island System, 11.

- Dorr, Henry C., The Planting and Growth of Providence, Rhode Island Historical Tracts No. 15 (Sidney S. Rider, 1882), 49. “The mill fixed the centre of the town at the North end, and long kept it there. Around and near it, those who were able, set their houses, and it became not merely the nucleus of population, but the place of public rendezvous and exchange. It served the same purpose as the meeting-house in early Massachusetts, or as the newspaper and insurance offices of later days.”

- Cady, John Hutchins, The Civic and Architectural Development of Providence (The Book Shop, Providence, 1957), 30.

- Farnham, Charles William, John Smith, the Miller of Providence, Rhode Island, Some of His Descendants (Rhode Island History, Rhode Island Historical Society, April 1963), 49-50; Waterman, Zuriel, Diary of a Doctor – Privateersman 1779 to 1781, Rhode Islanders Record the Revolution (Rhode Island Publications Society, Providence, 1984), 81.

- Rivas, Todd, Erosion Control Treatment Selection Guide, (United States Department of Agriculture (2006), 2-5.

- Dorr, The Planting and Growth of Providence, 14.

- Records of Deeds, Providence City Archives, (hereafter Deeds), Book 1, Page 4; Bridgham, Clarence S., Seventeenth Century Place Names of Providence Plantations 1636 – 1700 (Reprinted from the Rhode Island Historical Society Collections X, Providence, 1903), 20.

- Providence Town Papers 1772-1778 Transcription (Providence City Archive, 1776-B), 45.

- Ibid. (Providence City Archive, 1777-A), 6-7.

- Staples, William R., Annals of the Town of Providence (Knowles and Vose, 1843), 352 and 601.

- Providence Gazette, March 17, 1798, page 1, column 2.

- Chace, Henry R., Owners and Occupants of the Lots, Houses and Shops in the Town of Providence Rhode Island in 1798 (Livermore & Knight, Providence, 1914), Plate X.

- Providence Patriot, December 10, 1814, page 4, column 5.

- Deeds, Providence City Archive, Book 39, page 21.

- Deeds, Providence City Archive, Book 39, pages 50-54.

- Deeds, Providence City Archive, Book 43, page 112.

- Deeds, Providence City Archive, Book 37, page 173 (Olney’s Lane); Book 41, page 8 (Main); Book 41, page 58 (Bark Street).

21: Deeds, Providence City Archive, Book 43, page 230.

- Lockwood and Cushing, Map of the City of Providence and Town of North Providence by actual Survey 1835.

- Topographical Map of the City of Providence showing Proposed Sewerage System together with Sewers Already Constructed. Compiled in the City Engineers Office 1884 (Levanthal Map Collection Boston Public Library).

- Deeds, Providence City Archive, Book 76, page 1.

- Deeds, Providence City Archive, Book 43, page 230.

- Deeds, Providence City Archive, Book 43, page 239.

- Deeds, Providence City Archive, Book 43, page 245.

- Brown, William J., The Life of William J. Brown of Providence, R.I. (University of New Hampshire Press, Durham, N.H., 2006), 18.

- Deeds, Providence City Archive, Book 32, page 192 and Book 35, page 271.

- Deeds, Providence City Archive, Book 40, page 80.

- Deeds, Providence City Archive, Book 37, page 129.

- Deeds, Providence City Archive, Book 42, page 572.

- Deeds, Providence City Archive, Book 39, page 83.

- 1820 US Census, Providence, Rhode Island, Sheet 134.

- Deeds, Providence City Archive, Book 44, page 244.

- 1820 US Census, Providence, Rhode Island, Sheets 146 and 147.

- Providence Directory (Brown and Danforth, 1824), 57; Deeds, Providence City Archive, Book 47, page 16.

- Polta, Andrew T., “Disorderly House Keepers: Poor Women in Providence, Rhode Island, 1781-1832” (2018), Open Access Master’s Theses. Paper 1185. http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/theses/1185), 61.

- Trial of Daniel Gardner, Providence Gazette, October 9, 1822, page 4, columns 1-4.

- Deeds, Providence City Archive., Book 44, page 259; 1820 Census; Polta, Disorderly Housekeepers, 124.

- Providence Town Council Minute Books, V11, page 154.

- Providence Patriot, August 18, 1821.

- Deeds, Providence City Archive, Book 44, page 321.

- Brown, The Life of William J. Brown, page 18; Providence Town Papers Census of Black Housekeepers, PTP 112, Doc. 0039155, 1822 Census of Black Housekeepers, Sheet 3 Recto.

- Providence Gazette, December 21, 1822, page 2, column 5; Deeds, Providence City Archive, Book 44, page 244 and Book 44, page 287.

- Deeds. Providence City Archive, Book 47, page 170.

- Deeds. Providence City Archive, Book 49, page 111.

- Deeds, Providence City Archive, Book 47, page 211.

- Providence Directory (Brown and Danforth, 1824), 63.

- Providence Town Council Minutes, V11, Page 154. In Disowning Slavery, Joanne Pope Melish indicates grave-robbing was a significant problem for Blacks in post- revolutionary/early antebellum New England. See Melish, Joanne, Pope, Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and “Race” in New England, 1780-1860 (Cornell University Press, 1998), 185-88.

- Hard-Scrabble Calendar, Report of the Trials of Oliver Cummins, Nathaniel G. Metcalf, Gilbert Humes and Arthur Farrier (Privately Printed, Providence, 1824) (copy at Providence Public Library), 10.

- Hard-Scrabble Calendar, 26. For more on the riot, see Sweet, John Wood, Bodies Politic, Negotiating Race in the American North, 1730-1830 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003), 353-78.

- Deeds, Providence City Archive, Book 50, page 62; Book 52, page 64; Book 54, page 434.

- Independent Inquirer, February 23, 1826, page 4, column 1.

- Deeds, Providence City Archive, Book 52, page 385.

- Deeds, Providence City Archive, Book 56, page 205.

- Deeds, Providence City Archive, Book 54, page 434.

- Deeds, Providence City Archive, Book 54, page 433.

- Providence Directory, 1832 page 131, 1836 page 130, 1838 page 142.

- Deeds, Providence City Archive, Book 52, page 64.

- Providence Directory, 1832, page 133; ibid., 1836, page 133; ibid., 1838, page 147, ibid., 1844, Page 201.

- Deeds, Providence City Archive, Book 84, page 91.

- Rhode Island American, July 7, 1826, page 3, column 1.

- Providence Patriot & Columbian Phenix, May 9, 1827, page 3, column 6.

- Deeds, Providence City Archive, Book 51, pages 546-548.

- Manufacturer’s and Farmers Journal, May 2, 1853, page 2, column 5.

- Campbell, Paul, Glancy, John and Pearson, George, Images of America, Providence Police Department, Images of America (Arcadia Publishing, Charleston, South Carolina, 2014), 27.

- Providence Evening Press, December 21, 1872, page 3, column 5.

- The Providence House Directory (Sampson & Murdoch, 1895), 436, 476, and 601.

- Clarke, William E., Index to Street Maps on File in the Office of the City Clerk, 1761 to 1901, Providence City Archive (The Providence Press, Snow & Farnham, City Printers, 1902), 26.