Historian Seth Rockman’s deeply researched and thoroughly engaging new book, Plantation Goods, deserves to be on the shelf of all those interested in late 18th and 19th century America. Many years in the making, Rockman, a long-time (and still) professor of history at Brown University, unlocks the inner workings of the business of human bondage – the “material history of slavery” – shedding light on how “an archipelago of New England communities” and businesses in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Connecticut engaged with southern plantation owners to construct a market to sell them manufactured products for their enslaved people. The manufacturing of plantation provisions constituted a major business enterprise for many New England towns and villages, many of which were in the Blackstone Valley.[1] Plantation Goods is an important addition to the literature on slavery and American economic development. Rockman truly fills a void and his work will fundamentally reshape the ways in which readers, especially those in Rhode Island, engage with early America.[2]

While much has been written about slavery in Rhode Island and the state’s high-level participation in the Atlantic slave trade, only Rockman has managed to carry the story forward into the 19th century to cover the story of the manufacturing of plantation goods for sale to southern slaveowners. The most common product was so-called “negro cloth,” course clothing made for use by enslaved people on southern plantations. Approximately half the book deals with Rhode Island’s role in manufacturing plantation goods.

Rockman narrates the “entangled, dynamic, [and] mutually constitutive relationship that was forged between opportunity and oppression, slavery and freedom, the self-made and the slave-made in the American past” (page 12 of Plantation Goods). His book explores the tangled web created by the production of “negro cloth,” as Americans “sought to challenge British manufacturers for control of plantation markets” (page 57).[3]

Plantation Goods brings readers to a deeper understanding of the meaning of Charles Sumner’s famous phrase, “lords of the loom, lords of the lash,” as well as explaining the “unholy union” between northern manufacturers and “cotton planters and fleshmongers of Louisiana and Mississippi.” Rockman’s considerable skills as a writer enable him to track “negro cloth and cases of shoes from the communities where they were made, through the hands of merchants and marketers who distributed them, and into plantation spaces were slaveholders and the enslaved competed over their usage and meaning” (page 5). Shortly after the start of the Civil War in 1861, a British commentator noted that the North was “killing the goose that has laid their golden egg when they attempted to interfere with the people of the South, who have not only supplied [???] them with the raw material, but who have been their principal customers for all their manufacturers” (page 11).

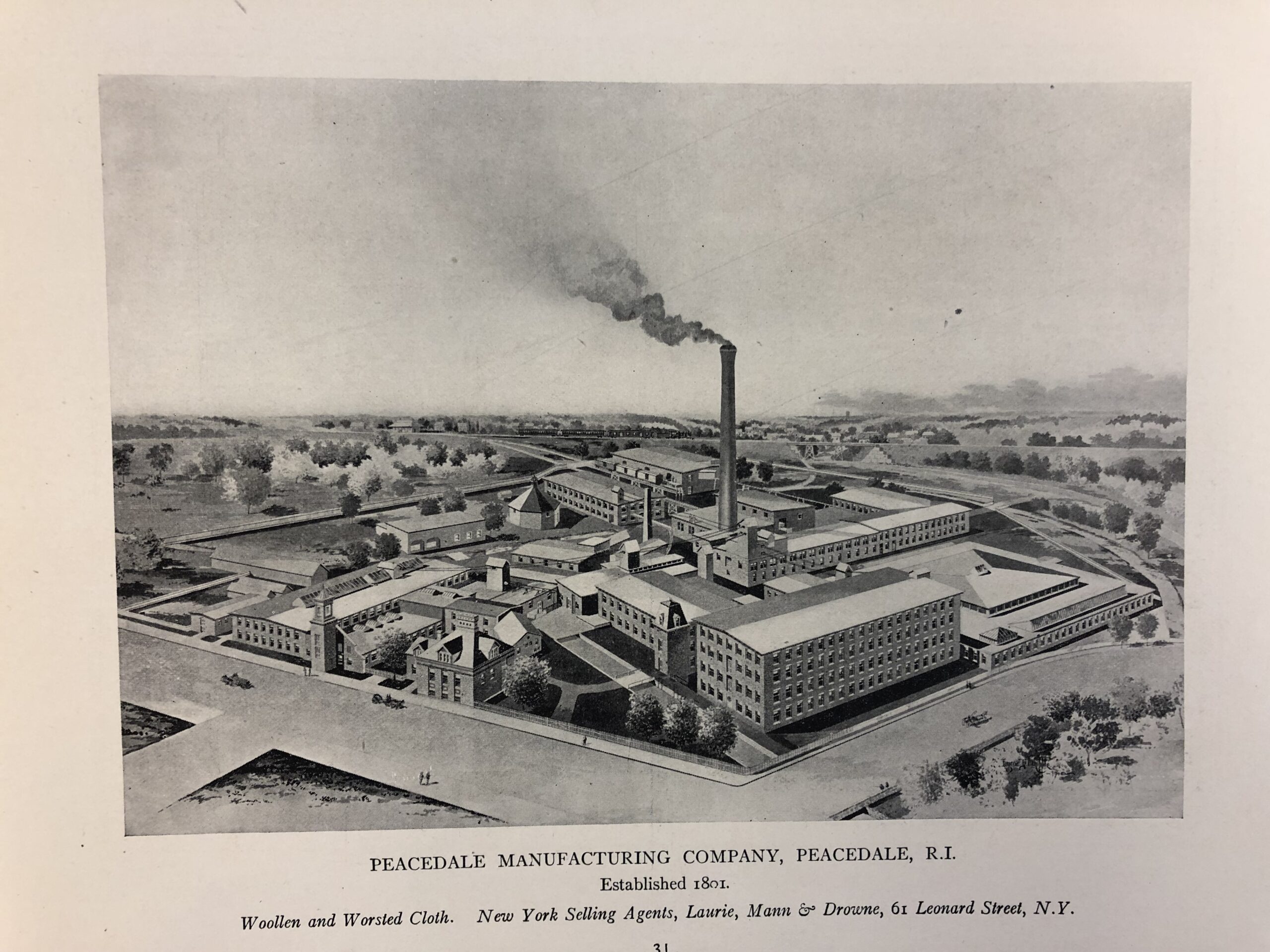

Drawing of the Peace Dale Manufacturing Company in Peace Dale, Rhode Island, circa 1890 (Board of Trade Journal)

Rockman’s discussion of the material culture of slavery also sheds light on the development of anti-Black racism in the North and how this virulent racism impacted political culture. As Rockman argues, plantation goods “acquired and shed racial meanings as they moved across space, from the point of production to the point of consumption and through many hands in between” (page 204). In addition, Plantations Goods furthers our knowledge of the inner workings of southern slaveholders and their concern for the laborer as a valuable commodity and the need to purchase plantation goods from a warped mindset of benevolence.

Beginning in the early 19th century, New England businessmen “mobilized the productive energies of small rural communities to provision a slaveholding regime that would soon stretch westward from the Atlantic seaboard to the frontier lands of Texas” (page 3). Northern communities were able, in Rockman’s phrase, to “offshore their slaveholding” so as to “reap the economic benefits of slavery at a safe distance,” while southern slaveowners “outsourced” the manufacture of essential plantation products “so that it could devote its energies to the lucrative production of agricultural commodities for the world market” (page 4). Ironies of ironies abound, of course, with enslaved workers on cotton plantations raising and baling raw cotton to send to northern firms, which in turn spun and wove the cotton into finished products that would then be sold to the South and used to mark Black workers as enslaved. At the same time, it was the growth of American industry that led to the development of the Whig Party, the party of choice for the majority of factory owners and the party whose northern adherents leaned heavily towards antislavery.

The author of the award-winning, Scraping By: Wage Labor, Slavery, and Survival in Early Baltimore (2009), Rockman conducted research in a vast array of libraries across the country to write his latest work. For readers of this journal, it is fair to say that no historian in recent years has done more work with the incredible collections at the Rhode Island Historical Society. This includes the Hazard Family Papers and Peace Dale Manufacturing Company Papers, which have only relatively recently been fully accessible to historians.

Rockman’s impeccable research does move beyond Rhode Island to include the workings of shoemakers in Massachusetts, including the Batcheller firm, along with factories devoted to the construction of axes and hoes in Connecticut, especially the Collins Company. But the operations of the Rhode Island merchants and factory owners looms large in his tale from start to finish.[4] In 1845, for example, 17 of the 40 textile manufacturing enterprises in Rhode Island specialized in “negro cloth,” more than any other state. In 1860, at the dawn of the Civil War, Rhode Island was ranked first in production of mixed cotton and woolen goods.[5] Almost all the cotton was raised in the South on slave plantations.

At the turn of the 19th century, Rowland Hazard Sr., invested his wealth gained from the selling of plantation commodities, such as rice and molasses, throughout the Atlantic world to manufacturing endeavors in southern Rhode Island. Hazard, who hailed from South Kingstown, married Mary Peace, the daughter of a prominent South Carolina family. In 1819, their sons Isaac Hazard and Rowland Gibson Hazard created the Peace Dale Manufacturing Company (based in Peace Dale, Rhode Island), which became one of the dominant manufacturing businesses in the state. As Rockman notes, Isaac and his younger brother Rowland “envisioned” making cheap goods for southern planters even before “they had much experience running a textile mill and before they had developed a competitive product” (page 2). No strangers to the South, they operated a store in Charleston, South Carolina, several months each year. In the decades before the Civil War, the “negro cloth” produced in the Hazard mills “traveled to the farthest reaches of the plantation frontier, and the brothers themselves were familiar faces in Charleston and New Orleans” (page 51).

In the 1830s, the Hazard brothers, initially Isaac and later Rowland, recognizing the growing shift of slavery to the southwest, adjusted their business accordingly. “I have always supposed there must be a great opening for negro cloths on the coast of the Mississippi and have been very desirous of getting the supplying of it,” wrote Isaac to Rowland (page 62). Rowland traveled extensively in the 1830s in the South, often from November to May, from Savannah to New Orleans, to conduct plantation sales.

The granite tower and many other buildings of the Peace Dale Manufacturing Company complex were built in 1847, replacing earlier wooden mills, some that were destroyed by fire in 1844. The tower can be seen in the drawing above. Photo taken in November 2024 (Christian McBurney)

Building on the work of historian Christy Clark-Pujara, Rockman details how the Hazard brothers became stalwart Republicans in the 1850s, complicating the picture of the makeup of the party of Lincoln.[6] The Republican Party, as Rockman notes, “was a natural home, even for New England businessmen whose livelihoods centered on plantation provisioning” (page 83). A decade before his conversion to the Republican Party, Rowland Hazard worked tirelessly to free Black sailors who had been jailed in southern prisons. At the same time, Hazard was vehemently anti-abolitionist, believing that northern abolitionists were agitators inflaming sectional tensions.[7] He never exhibited any qualms about being a leading provider of negro cloth to southern plantations and the intertwined relationship between his business and the propagation of slavery. Rather, the Hazards “saw their business with the South as sustaining national prosperity, and their enduring friendships with prominent slaveholders as functioning to hold the nation together in the face of countervailing—northern and southern—forces of fragmentation” (page 83). ). As Rockman notes, Rowland and Isaac turned their factories away from producing Double Kersey and plantation ready-made clothing in the 1850s. In 1855, a devastating fire destroyed numerous buildings and equipment for producing cloth for plantation slaves and, as a result, the company transitioned to the production of shawls and cassimeres for growing northern markets. Hazard fabrics continued to “find markets in the South, but outfitting slaves ceased to be their primary business,” maintains Rockman. It is important to note that in the 1850s, Rowland Hazard was also heavily involved in the operation of the Washington County Bank, along with the new Republican Party, leaving little time for travel to the South as he had done in previous decades.

After the Civil War, northern goods continued to flow to the South. The costs were now “transferred to the formerly enslaved under annual contracts that gave employers and affiliated storekeepers maximal ability to set prices and settle balances” (page 354). By the end of the 19th century, many New England firms relocated to the South in search of cheaper labor, beginning a long process of deindustrialization in the North. In the end this process, “made it all the easier to forget that free families in Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Massachusetts had once earned their living weaving cloth and stitching shirts for enslaved men and women on the plantation frontier” (page 356).

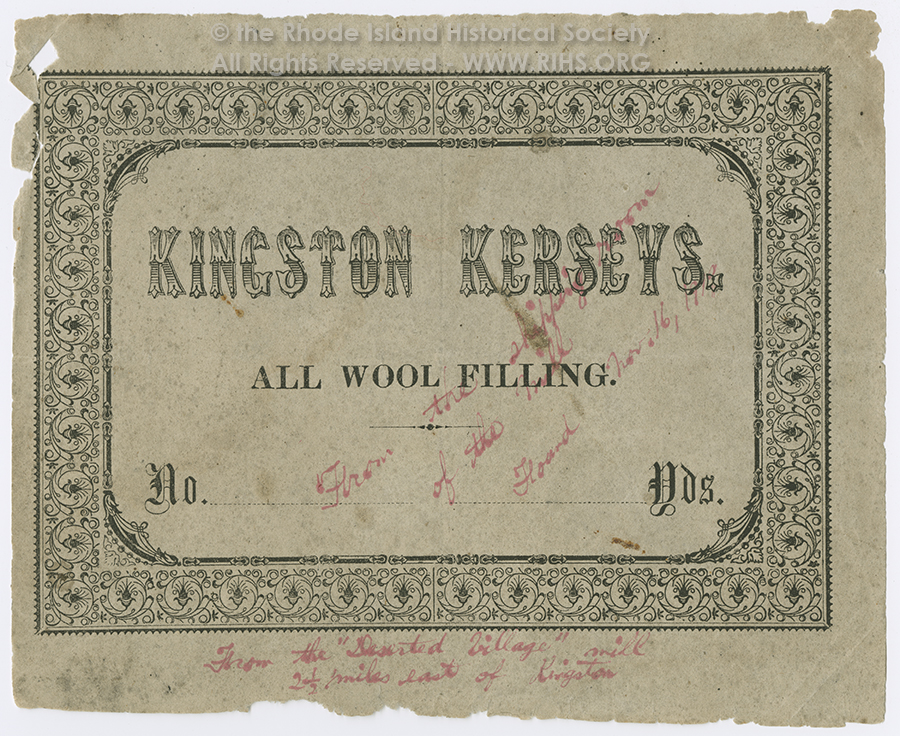

Fabric label. Kingston Kersey All Wool Filling, no date, Ephemera Collection, Box 4, Rhode Island Historical Society. RHi X17 2824. The mill that made the label was probably at Mooresfield, about 2 1/2 miles east of Kingston. Kersey was made into clothing for enslaved people on southern plantations (Rhode Island Historical Society)

By recapturing the largely forgotten past of plantation goods, Seth Rockman has crafted an invaluable work of history that speaks powerfully to our own historical moment as we deal with the “fraught relationship of remote consumers and producers” and an “interconnected world defined by complex moral entanglements” (page 357). For Rhode Island historians, Rockman’s research into the lives of the Hazard brothers will hopefully spark additional research into the development of the Rhode Island Republican Party in the 1850s and how business owners engaged in the trade of plantation goods could devote themselves to a party dedicated to slavery’s demise.[8]

Endnotes:

[1] See Rockman’s essay in the following valuable collection of essays, A Landscape of Industry: An Industrial History of the Blackstone Valley (2009), 110-131. [2] For those interested in the literature here are six books to start off with: See Peter Kolchin’s classic work, American Slavery, 1619-1877 (1993); James Oakes, The Ruling Race: A History of American Slaveholders (1982); James Oakes, Slavery and Freedom: An Interpretation of the Old South (1990); Edward Baptist, The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism (2014); Walther Johnson, River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom (2017); and Sharon Murphy, Banking on Slavery: Financing Southern Expansion in the Antebellum United States (2023). [3] Several important works on slavery in Rhode Island, its participation in the Atlantic slave trade, and the politics of emancipation include Jay Coughtry, The Notorious Triangle: Rhode Island and the African Slave Trade, 1700-1807 (1981); Charles Rapleye, Sons of Providence: The Brown Brothers, the Slave Trade and the American Revolution (2007); Christian McBurney, “Cato Pearce’s Memoir: A Rhode Island Slave Narrative,” Rhode Island History (Winter/Spring 2009), 3-25; and Christian McBurney, Dark Voyage: An American Privateer’s War on Britain’s African Slave Trade (2022). See also the discussion of Rhode Island in Joanne Pope Melish’s classic, Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and “Race” in New England, 1780-1860 (1998) and John Wood Sweet, Bodies Politic: Negotiating Race in the American North, 1730-1830 (2003). A precursor to Rockman’s book is Christy Clark-Pujara, Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island (2016). [4] Ironically, the Collins Company would later fulfill an order from the murdering abolitionist John Brown in the late 1850s. Brown sought thousands of pikes to help instigate a slave insurrection in the South. [5] See Madelyn Shaw, “Slave Cloth and Clothing Slaves: Craftsmanship, Commerce, and Industry,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts (2012). Accessed online on September 28, 2024, at https://www.mesdajournal.org/2012/slave-cloth-clothing-slaves-craftsmanship-commerce-industry/. [6] See Clark-Pujara, “The Business of Slavery and Anti-Slavery Sentiment: The Case of Rowland Gibson Hazard—An Anti-Slavery ‘Negro Cloth’ Dealer,” Rhode Island History, vol. 71, No. 2 (Summer/Fall 2013), 35-55 (accessed on September 28, 2024, at https://www.rihs.org/history_journal/rhode-island-history-journal-vol-71-summer-fall-2013/). [7] For a discussion of antislavery activism in Rhode Island in the 19th century, see Deborah B. Van Broekhoven, The Devoting of These Women: Rhode Island in the Antislavery Network (2002) and Erik Chaput and Russell DeSimone’s article for The Online Review of Rhode Island, “Third Century of Liberty?: Thomas Wilson Dorr and Debate Over the Gag Rule in Rhode Island, 1835-1836 (accessed on September 28, 2024, at https://smallstatebighistory.com/third-century-of-liberty-thomas-wilson-dorr-and-debate-over-the-gag-rule-in-rhode-island-1835-1836/). [8] For an interesting examination of the antislavery agenda of the Republican Party, see James Oakes, The Scorpion’s Sting: Antislavery and the Coming of the Civil War (2014). For Rhode Island delegates, including Rowland G. Hazard, failing to cast a single vote for Abraham Lincoln in the first round of voting at the Republican Party Convention in 1860, see Christian McBurney, “Rhode Island Fails to Vote for Lincoln for President at Nominating Convention!,” The Online Journal of Rhode Island History (accessed on September 28, 2024 at https://smallstatebighistory.com/rhode-island-fails-to-vote-for-lincoln-for-president-at-nominating-convention/).