In one of his oft-repeated observations, Benjamin Franklin remarked “in this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.”[1] But Franklin would have exempted colonial Rhode Island, where only mortality was assured. It was a long-established tradition for individuals in Rhode Island and even entire towns to avoid or to even outright refuse to pay their taxes. When Rhode Islanders could not avoid them, they postponed them for as long as possible. To get colonists to pay taxes at all, the General Assembly deferred to local officials to assess and collect taxes, and allowed local courts to adjudicate disputes over property estimates. Trust in the valuation process at both the local and provincial level was essential or levies would be refused. Evidence from actual rates and property lists also suggest that a system of negotiation of an individual’s tax assessments had evolved, that not only considered the value of the individual’s property but factored in debts and other exigencies. These deeply-held traditions were akin to the English moral economy, in which payment for bread and other basic necessities were based on one’s ability to pay.[2] This system stands in stark contrast to the top-down, non-negotiable taxes imposed by Parliament beginning in the 1760s. Local Rhode Island tax records contemporaneous with the turmoil in Massachusetts over the Tea and Intolerable Acts provide another perspective as to what Rhode Island colonists found unfair about the British levies of the 1760s and 1770s that ultimately led them to the American Revolution.

In Alvin Rabuska’s monumental 2008 work, Taxation in Colonial America, he notes early in his discussion of Rhode Island that “[t]ax resistance was a prominent feature of life in the colony.” Rhode Island was founded in 1636 “as a collection of autonomous towns” that did not attempt to levy colony-wide taxes until 1658. Soon thereafter the colony government needed to raise a tax to pay Dr. John Clarke, working in London to secure a royal charter after the Restoration of King Charles II in 1660, “but [they] met with difficulty securing compliance.” In 1664, the town of Warwick outright refused to reimburse Dr. Clarke. The Warwick town meeting complained that their representatives were not at the Assembly when the tax was approved—an early example of “no taxation without representation”—and that no provincial taxes should be paid until the colony surveyed and defined town boundaries. Why should Warwick residents want to pay taxes on lands that might well lie in Providence? It was a valid point.[3]

Soon Providence taxpayers refused to pay their taxes as well. Rhode Island’s founder Roger Williams remarked, “Some say they will pay if all do: Some are against all Government and Charters and Corporations: Some are not so and yet cry out against thieves and Robbers who take anything from them against their wills.”During the brief Dominion of New England in the 1680s, Governor Edmund Andros established a top-down style of management across the region that ruled by decree. After the revocation of Rhode Island’s charter, he abolished the Rhode Island General Assembly and banned regular town meetings save the annual election of local officials. But Andros achieved little in the way of actual governing in Rhode Island as he lacked the cooperation of the citizenry, who submitted to central authority only when their town meetings held a measure of control over it. In defiance of Andros, Rhode Islanders held multiple town meetings in some towns, none in others and especially, they did not pay taxes.[4]

Once the Colony’s charter was restored after the fall of the Dominion, the General Assembly was reorganized into a bicameral body, with its lower chamber, the House of Deputies, given “exclusive power to initiate money bills.” Since the deputies were elected twice a year every April and August in their town meetings, local governments maintained close control over their representatives and the agenda of the General Assembly. In 1703 a joint commission from Connecticut and Rhode Island reached a tentative agreement on their respective borders and in 1708 the General Assembly ordered a survey of the colony. The drawing of town boundaries should have closed an oft-used justification for freemen to refuse to pay colony taxes, yet many still refused to pay. Nearly twenty percent of all the taxes levied between 1690 and 1710 remained outstanding in 1713. But that eighty percent of the colony’s taxes had been collected by 1713 was a vast improvement over the near-universal disregard for tax collection in the seventeenth century.[5]

In 1710 the General Assembly ingeniously sidestepped the issue of taxation, by resort to the printing press. For about forty years during the first half of the eighteenth century, provincial taxes in Rhode Island were virtually nonexistent and the economy was greatly stimulated by the success of the colony’s land banks. These were not actual banks—banks in the modern institutional sense were not established in Rhode Island until the 1790s. Land banks were emissions of paper money backed by mortgages on land. Rural landowners mortgaged their property in exchange for some amount of paper relative to the value of their land. The loans generated interest, which the colony government used to defray operational costs. Meanwhile the paper provided a medium of exchange for the colony’s freemen. That the paper money often depreciated in value made it easier for Rhode Island farmers to pay back their debts, and Rhode Island’s plentiful paper supply gave Newport an advantage over Boston, whose money supply was based on specie and was more tightly constrained by a royal governor.[6]

But Rhode Island’s tax holiday was not to last forever. Parliament’s Currency Act of 1751 made it illegal for the General Assembly to issue of any more bills of credit not backed by taxes and “by the middle of 1754,” according to tax historian Alvin Rabushka, “the colony faced insolvency.”[7] Two political factions emerged at this time, one based in Newport and led by Samuel Ward from Westerly, and the other headquartered in Providence under the direction of Stephen Hopkins, originally from Scituate, Rhode Island. The main goal of these two factions was the control of political patronage and taxation. However, actual rates were assessed by men locally elected, and not colony officials or party affiliates. This concession to localism granted towns considerable leeway in the collection of colony rates when controversies over their fairness arose during the political battles known as the Ward-Hopkins controversy in the 1760s.

As for the tax collection process itself, tax assessors and tax collectors held a set of interrelated responsibilities. At town elections, Rhode Islanders took these positions only under duress. Colony laws imposed a thirty-shilling fine for refusing the office of assessor or collector. Recognizing that these offices were unpopular, Rhode Island law also stated that no man could be compelled to take on either position “oftner than once in Seven Years.” Rhode Island property owners were entrusted to turn in a self-assessment of their ratable property. When taxpayers refused to provide a list, the assessors were empowered by law to “guess and rate the estates.” Persons that refused to provide a list at all could not seek remedy later if they thought they had been overtaxed. The assessors were authorized to disregard lists they suspected were undervalued, but if the taxpayer believed they were being unfairly overtaxed, they could seek remedy afterward in the local Court of the General Sessions of the Peace. Finally, unlike the present day where local property taxes are inevitably due every year, in the colonial era the town’s bills were allowed to accumulate and local taxes were assessed only when it became critical to pay the town debt.[8]

Now let us turn to an actual example. South Kingstown, Rhode Island has one of the most complete set of town records of any community in the state. South Kingstown also developed a unique economy in colonial New England. Settled by land speculators from Newport after King Phillips War, it was at the center of the so-called “Narragansett Country,” fertile coastal farmlands comprised of plantations worked by African slaves and indentured servants whose produce was sold on the Atlantic market. At the center of the most productive agricultural region in Rhode Island, the Narragansett planters were among the most wealthy and powerful men in the colony. South Kingstown was the county seat for King’s County (renamed Washington County in 1781) and the courthouse at Tower Hill and later, at Little Rest (renamed Kingston in 1825), served as the colony’s capitol when the General Assembly met there about once a year (Rhode Island had a system of rotating capitals).[9]

In the 1760s, South Kingstown’s town meeting levied taxes in only seven out of ten years. On the average, between 1744 and 1774, the town assessed local taxes less than twice in every three years. Annual payment of local taxes did not become permanent until a revision of town highway ordinances in the 1790s required the yearly payment of road taxes.[10] During the Ward-Hopkins controversy of the 1760s, South Kingstown was assessed the second highest property valuation in the colony. This was partly because the town’s coastal plains were the best farmland in the colony, and partly because the region’s plantation economy, based as it was on slave labor, was so prosperous, but also because once in control of the General Assembly, the Hopkins faction punished the town for supporting Samuel Ward. For a time, South Kingstown’s town meeting refused to pay its colony taxes and attempted to negotiate with the General Assembly for a modification of the town’s valuation, but to no avail.[11] Eventually the colony government forced the town to accept the new valuation and pay its overdue taxes in 1770.[12]

Altogether there are thirty-two extant colonial-era rates and assessments from the founding of South Kingstown in 1723 to the outbreak of the Revolutionary War in 1775. Usually, assessment lists note the taxpayer and the property values, while the rates list the actual tax amount. Additional information is only given when the taxpayer died, moved away, or to differentiate residents with the same name. However, during a two-year period from 1773 to 1774, South Kingstown tax assessors also kept track of who submitted estate lists suspected to be inaccurate, and identified which of these lists had been sworn to and which lists to which taxpayers had refused to swear. The reasons for this are not found in the colony laws, which did not require assessors to keep such extensive records, nor did the town meeting record passage of an ordinance requiring it either. Neither it is clear exactly when this practice began and ended, as the town’s tax records for the period are incomplete. The tracking of who had and who had not sworn to their property lists, which began sometime in the early 1770s, ended during the Revolutionary War.

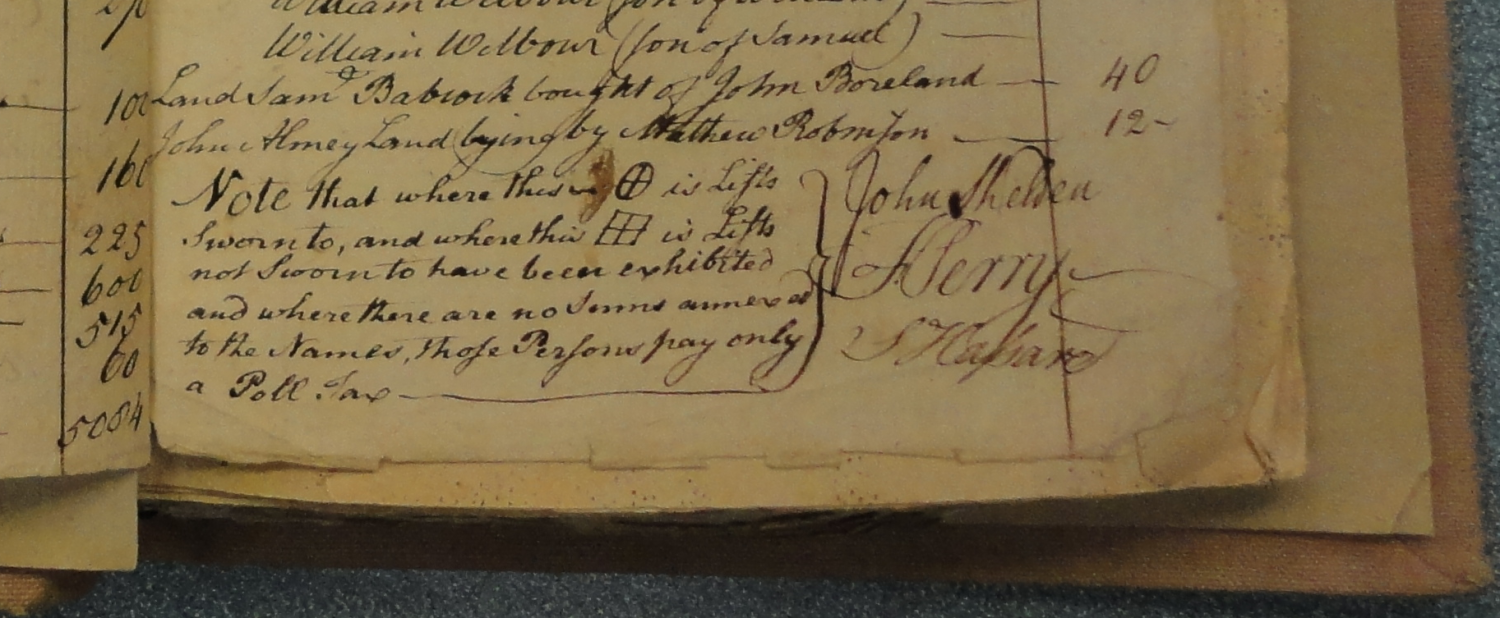

The election of tax assessors was typically uneventful. But in June 1772, only a few days after angry citizens from Providence attacked the H.M.S Gaspee off the coast of Warwick and burned her down to the waterline, the major concern at South Kingstown’s second June town meeting was not the violent destruction of the British customs schooner. Rather, the first June meeting had elected two ratemakers with “no freehold Estates.” Men without any real property could not “serve in sd Capacity agreeable to Law.” On June 16, 1772, a third town meeting “especially called” for the occasion chose two qualified men with previous experience to serve as the town’s new ratemakers alongside the remaining ratemaker, eight-term tax assessor John Sheldon. Samuel Hazard had been a tax assessor in 1771, while Freeman Perry had served in 1764.[13]

Unfortunately, the rates drawn up by the 1772 tax assessors have not been preserved. But for the following year, in which records are available, the tax lists record which taxpayers were asked to swear to the lists they presented. In 1773, sixty-six of the town’s two hundred and eighty taxpayers with rateable estates were asked to swear to their lists, which amounted to nearly one-quarter of the town’s total taxpayers. Of the taxpayers who were asked to swear to their lists, over 80 percent did so. And of the three tax assessors in 1773, only one, Stephen Hazard, had no prior experience; Freemen Perry was into his third term as tax assessor and John Sheldon his tenth.[14]

In the following year of 1774 the number of taxpayers asked to swear to their lists fell from sixty-six to fifty-four men, an 18 percent decrease, but the number of persons refusing to swear to their lists increased from 4 percent to 50 percent. Of those asked to swear to their lists, exactly half of them, twenty-seven, refused to do so.[15] At the same time the percentage under dispute was almost identical to that of the previous year— 37.45 percent of the total in 1774 versus 36.12 percent of the total in 1773. What might account for the significant rise in the number of refusals?

There were two important differences in these assessments. In 1773 the town did not levy a tax on itself, but it was assessed a £372 colony tax. In 1774, the town paid the same amount in colony taxes, but the town meeting also voted a £300 tax on itself, which nearly doubled the amount that taxpayers were assessed that year. The other key difference is that the three tax assessors in 1774 were far less experienced than the men that served the previous year. Two of the 1774 assessors, Samuel Segar Jr. and Jeffery Watson Jr., were first-timers, while Nathaniel Perkins, the only assessor with previous experience, was serving only for his second term. Undoubtedly, some taxpayers who swore to their lists before a tax assessor took their rates to be adjudicated before the Court of the General Sessions of the Peace. Testimony before the local justice of the peace might explain why so many residents refused to swear to their lists in 1774. Unfortunately, South Kingstown’s earliest Justice of the Peace records date from the mid 1780s and none are extant from the 1770s. Nonetheless, a likely explanation is that the freemen distrusted the 1774 assessment because of the relative lack of experience on the part of the assessors that year. Combined with the increase in total taxes, some freemen apparently balked at paying rates assessed by “green-horn” tax assessors.

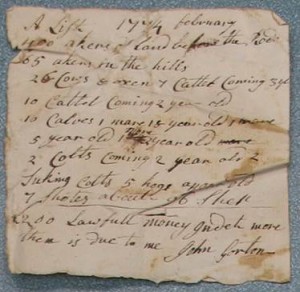

Fortuitously, a small number of actual property lists by individual South Kingstown taxpayers from those same two years are also preserved in the town records: six lists from 1773 and eight lists from 1774. A close read of these property lists, all of which are scrawled on scraps of paper, shed even more light into the interactions of tax assessors with the assessed for these two years. Samuel Tefft, a widely-respected town moderator chosen to preside over a record 113 town meetings over his lifetime, complained in his 1774 property list that he was “more in Debt than my hole movable are worth.” John Robinson stated in his October 1773 list that his rateable estate consists of “About 400 Acars of Clear land + About 170 acars of Swamps and Bushes 55 Cows + 10 oxen 5 horses 100 sheep 2 Negros About as mych monny Due to me as I owe . . . .” After listing his property, Jeremiah Carpenter explained that he was “In Debt 150 pounds Lawfull money,” while Tennant Tefft listed his rateable real estate as “125 acors of Land parster medow and swamp . . . ” John Gorton detailed a thriving farm: 465 acres of land, 53 cattle, 7 horses, 5 pigs, 7 “shoter” and nearly 100 sheep but then added that he was “£200 Lawfull Money Indet more then is due to me” (see image to the left of this article).Carder Hazard, apparently ill and “confined at home,” sent in his list under wax seal. After enumerating his property but before he signed his name “in Haste,” he proclaimed that “The Obligations against me amount to the balance of my stock, which is my Rateable Estate.” Silas Niles rented the Point Farm, the most valuable property in South Kingstown. His plantation is listed at £9,000 in the 1773 valuation. Niles claimed ownership of 95 cattle (63 older than four years, 14 three-year olds, and 18 two-year olds), 12 horses also described by age, 3 hogs, 656 sheep, 4 “Negros 16 years old and not 50 years old,” and two dozen pieces of plate silverware. Finally, Niles complained “Money I have None . . . but I am in Debt 1050 Dollars.”[16]

On one level, these lists document the economic plight of Narragansett planters at the point when the commercial plantation system was, for numerous reasons, losing viability.[17] But what these lists also have in common is a persistent effort by taxpayers to make their property appear less valuable by emphasizing the amount of “swampland” in their possession or by categorizing livestock into age groups, some of which were less valuable than others. Even more telling is the listing of debt, which has absolutely nothing to do with the value of taxable property. Such information is not superfluous, provided it were the basis for a taxpayer to negotiate their tax assessment on grounds that considered more than the face value of their property. In a moral economy, establishing value and the ability to pay is an important consideration when settling on a “just price,” or in this case, an equitable tax bill. Tax assessors wielded considerable authority within the letter of the law, and apparently exercised some modicum of discretion as well. South Kingstown’s property lists imply unwritten expectations of negotiation on the part of tax assessors based on the taxpayer’s need and circumstances, in a community whose economic basis was in terminal decline. The near ubiquitous inclusion of debts by taxpayers in this sample of property lists suggests that financial circumstances were factored into the individual rates, either by the assessors themselves at the time of the assessment or by justice courts on appeal.

These records provide us with another layer of insight into Rhode Island’s reaction against the Stamp Act of 1765 and Tea Act of 1773. Rhode Islanders had never been amenable to paying taxes. They took an early stand against taxation without representation. Tax assessment and collection in Rhode Island evolved into a political process subject to negotiation and appeals, embedded in legal procedures that considered one’s ability to pay for the tax to be considered just. Local control over tax assessment and collection, and trust in the ability of officials was essential. As events during the Dominion of New England and the Ward-Hopkins controversy proved, Rhode Islanders would peacefully accept higher taxes, albeit grudgingly (as was the case with the town of South Kingstown in 1770) only as long they had some input into the political process through their town meeting and their representatives in the General Assembly. And even when entire towns balked at paying provincial taxes, they still maintained local control over tax assessment and collection.

The process of tax valuation and collection was a personal, face-to-face experience in colonial Rhode Island. For a tax to be accepted as valid, it had to be assessed by qualified men known and trusted by the community. Taxes imposed from afar by Parliament in London, England were another matter entirely.

For Rhode Islanders, the changes in imperial taxation beginning in 1764 took place hard on the heels of the imposition of new provincial taxes, taxes that had been implemented in 1754 only a decade earlier and after nearly 120 years of negligible colony taxes or even no taxes at all. Rhode Islanders in the 1770s were still acclimating to a harsh currency reform that had both eliminated the easy money derived from land banks and required the imposition of regular provincial taxes for the first time since the colony’s founding.

The British, as an emerging modern economy and military superpower, regarded the imposition of additional taxes as an existential necessity following a staggering war debt from the Seven Years War and the enormous administrative overhead needed to manage their new global empire, and did not consider payment of taxes open for discussion or negotiation.[18] But Rhode Islanders would have perceived these new imperial taxes—non-negotiable at both the assessment and legislative level—as a violation of their traditional rights. The local unrest that ensued over these two conflicting world views sowed the seeds of Rhode Island becoming the first colony to declare its independence from Great Britain and joining the other colonies in the American Revolution.

[Banner Image: South Kingstown tax assessment for 1773 sworn to by Commissioners John Sheldon, Freeman Perry and Stephen Hazard (South Kingstown Town Hall)]This article is based on a paper presented at the April 20, 2013 spring conference of the New England History Association entitled “£200 Indet more then is Due Me: Taxation and Negotiation in Colonial Rhode Island.”

Dedicated to the memory of Kenneth M. Gardner, who whose 90th birthday would have been on March 20, 2015.

Notes

[1] Benjamin Franklin, Letter to Jean-Baptiste Leroy [Nov. 13, 1789] [2]The use of the term moral economy is based on the definition found in E. P. Thompson, “The Moral Economy of the English Crowd in the Eighteenth Century,” Past and Present 50, no. 1 (Feb., 1971): 78-79. [3] Alvin Rabushka, Taxation in Colonial America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008): 186-89. [4] Sydney V. James, The Colonial Metamorphoses in Rhode Island: a Study of Institutions in Change (Hanover: University Press of New England, 2000): 54-8 and Neil Dunay, Norma LaSalle, and R. Darrell McIntire,Smith’s Castle at Cocumscussoc: Four Centuries of Rhode Island History (East Greenwich: Meridian Printing Company Inc., 2003): 18. [5] James, Colonial Metamorphosis: 117-129; see also Rabushka, Taxation in Colonial America: 387-390. [6] Except in 1744, from 1713 to 1754 the colony of Rhode Island levied no colony taxes on property. Sydney V. James Colonial Rhode Island: A History (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. 1975): 170-185, 275-282, 291. [7] Rabushka, Taxation in Colonial America: 610. [8] Acts and Laws of the English Colony of Rhode-Island and Providence-Plantations, in New-England, in America: Made and Passed Since the Revision in June, 1767 (Newport: Samuel Hall, 1767): 87, 219-23, 251, in the Rhode Island State Archives, Providence RI. [9] Christian M. McBurney, “The South Kingstown Planters: Country Gentry in Colonial Rhode Island,” Rhode Island History 45, no. 3 (August 1986): 81-94; see also Christian M. McBurney, “The Rise and Decline of the South Kingstown Planters, 1660-1783,” BA thesis, (Brown University, 1981) (available at South Kingstown libraries). [10] James, Colonial Rhode Island: 136; Colonial Metamorphosis: 161. South Kingstown assessed no town taxes in 1750, 1752, 1764, 1765, 1767, 1768 (a tax was voted in 1768 but collection postponed until June 1769), 1771, 1773, and 1775. See South Kingstown Town Meeting Records Vol. I, passim (hereafter referred to as SKTMR I), located in the South Kingstown Town Hall, Wakefield, RI. [11] This is an example of democratic localism, the deference shown to Rhode Island town meetings by the General Assembly, the regular use of initiatives and referendums, and, as in this instance, the influence town meetings exerted on the legislature through petitions and instructions given to the town’s representatives to the General Assembly. Democratic localism emerged while Rhode Island’s provincial government was governed under the Parliamentary Patent of 1644, and was maintained as an “ancient” liberty of the towns even after the Royal Charter of 1663 superseded the patent, and was practiced into the nineteenth century. Historian Irwin Polishook described democratic localism as “a product of popular control of the General Assembly by the majority of voters and the vital role of the town as an institution of political life.” See Irwin H Polishook, Rhode Island and the Union, 1774-1795 (Evanston: Northeastern University Press, 1978): 27 and John P. Kaminski, “Democracy Run Rampant: Rhode Island in the Confederation,” in The Human Dimensions of Nation Making: Essays On Colonial and Revolutionary America, ed. James Kirby Martin (Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 1976): 243-46. [12] Rhode Island Acts & Resolves, , I, February 1769: 82; February 1770: 99-100; May 1770: 17-18; June 1770: 23-24; September 1770: 49-50, in the Rhode Island State House Library, Providence RI; SKTMR I: 341, 347, 350-51, 352-54. [13] SKTMR I: 364-5, 358. [14] “February 9, 1773 Valuation Bill:” 1-20, Tax Lists 1773-1791 South Kingstown, in SK Tax Lists 1773-1913, South Kingstown Town Hall. [15] “March 30, 1774 Valuation Bill”: 1-22, Tax Lists 1773-1791 South Kingstown, in SK Tax Lists 1773-1913, South Kingstown Town Hall. [16] These tax lists I discovered serendipitously while looking through a box of voting records. One of many folders labeled “Voting Lists” actually contained these (and other) taxpayer property lists; the folder has been renamed “Property Lists for Tax Assessors, 1773-1786.” “Samuel Tefft Esq. Property List, 1774” in Town Clerk Records, South Kingstown Town Hall; “John Robinson’s Property List, October 25, 1773,” in Town Clerk Records; “Jeremiah Carpenter Property List, March 12, 1774,” in id.; “Tennant Tefft Property List, AD 1774” ,” in id.; “John Gorton Property List, February 1774” in id.; “Carder Hazard Property List, April 2, 1774,” in id.; “Silas Niles Property List, March 1, 1774,” in id.; February 9, 1773 Valuation Bill: 1-20, South Kingstown Town Hall. [17] Christian McBurney, “The Rise and Decline of the South Kingstown Planters, 1660-1783:” 198-216. [18] According to the Internet site Tax History Project, “The British Government had borrowed heavily from British and Dutch bankers to finance the war, and as a consequence the national debt almost doubled from £75 million in 1754 to £133 million in 1763. In order to address this onerous liability, British officials turned to larger import duties on enumerated goods like sugar and tobacco, along with a series of high excise (sales) taxes on goods such as salt, beer, and spirits. This taxation strategy tended to burden consumers disproportionately. In addition, government bureaucracy expanded in order to collect the needed revenue. As the number of royal officials more than doubled, Parliament delegated new legal and administrative authority to them… [T]he war exposed the weakness of British administrative control in the colonies on various fronts. The subsequent efforts on the part of royal officials to rectify these deficiencies and collect unprecedented amounts of revenue violated what many American colonists understood as the clear precedent of more than a century of colonial-imperial relations.” Tax History Project, Tax History Museum (n.d.), The Seven Years War to the American Revolution. www.taxhistory.org. Retrieved February 18, 2015.