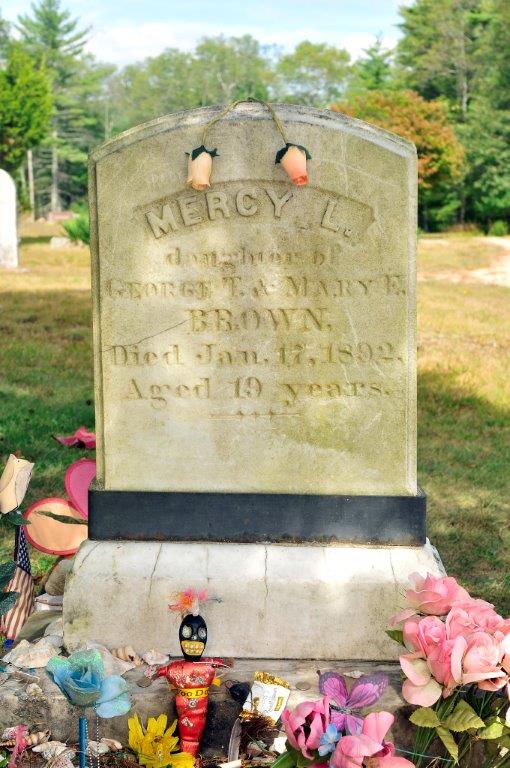

No doubt about it, at this time of year, South County’s most famous brother and sister have to be Mercy and Edwin Brown. One hundred and twenty-three years after their sad deaths, the vampire tale is so widely known that it was even recounted in the October 2012 edition of Smithsonian Magazine. And every Halloween, it seems Mercy Brown, Exeter’s most famous person, gets just a little more publicity and becomes just a little more notorious. Sadly, the public telling of her tale, the story of that day in March of 1892, seems to have centered on country-bumpkin ignorance and superstition. But in my view, that is not the key to the story.

What do I know about Mercy Brown, you might wonder? Well, first off, I do know that no one ever called her Mercy, her first name. Like so many folks with Swamp Yankee roots, myself included, her first name was strictly honorary, a way to remember a dearly loved grandparent. Everyone who knew her called her by middle name, Lena.

I can also tell you for sure that the very last person to look at her after she died before that coffin lid closed for the first time was the family undertaker, the man whose first name I bear, big George T. Cranston. And the last person who gazed upon that same visage as the coffin closed for the second time was her family doctor, Harold “Doc” Metcalf of Wickford. The Brown family with deep roots in Exeter had this Wickford connection because Lena’s brother, Edwin, known locally as Eddie, worked as a clerk in George T. Cranston’s general store, The Farmer’s Exchange & General Variety Store at Collation Corners just west of the village.

Chestnut Hill Baptist Church meetinghouse, constructed in 1838, is a fine example of a Greek Revival style country church, is located on Ten Rod Road in Exeter, in a rural and sparsely populated setting.

George Brown’s wife, Mary Eliza, in 1883 was the first in their family to die of tuberculosis, followed in 1888 by their eldest daughter, Mary Olive. Two years later, in 1890, another daughter, Lena, became sick. Only nineteen years old, in January 1892 she was buried in the cemetery behind the Chestnut Hill Baptist Church in Exeter. In 1891, George’ son Eddie, contracted the disease. George Brown, was beside himself over the loss of his beloved family members and the threat to his son Eddie. They called it consumption back then, the most common cause of death in America at that time. It was truly the scourge of the 18th and 19th centuries. Tuberculosis literally consumed a person at that time, and sometimes it consumed entire families, and occasionally even whole communities. No one then understood that tuberculosis was caused by a germ and was a communicable disease. If you could have, in private, pulled a physician like Doc Metcalf aside and gotten him to be quite honest, he would have told you, “There is nothing I or any other medical professional can do about consumption; it is in the Lord’s hands.”

So, it is within that context that we contemplate the events of March 17, 1892, the day that a very reluctant Doc Metcalf witnessed the exhumation of the three bodies of the women of George Brown’s family by a small cadre of unknown Exeter residents. Neither George Brown, who could not bear to see it, nor Eddie, who was at death’s door, was present at the time. My ancestor, George T. Cranston, was not there either. He had buried them all, and he knew they had truly died and would have nothing to do with an exhumation.

George Brown allowed his wife and two daughters to be exhumed and examined, and he allowed the still extant heart and liver of Lena to be removed. If he had asked George Cranston why this was so two months after Lena’s burial, George would have told him, “She died and was buried in the winter, her earthly remains were frozen when they entered the grave and would stay that way long into the spring thaw.” George Brown then allowed Lena’s removed organs to be burned to ashes on a nearby bedrock outcrop and then, with trepidation, fed these ashes to Eddie in the hope that he would not die. This effort was not based on science, but on the suspicion that vampires had killed members of the Brown family. Because Lena’s heart and liver were seen to have blood still in them, locals thought that only by performing this strange ritual could Eddie’s life be saved. What did they know about consumption? They knew about vampires.

I imagine that Doc Metcalf and perhaps even George Cranston and their shared spiritual advisor Elder Edwin Wood counseled George Brown that this was not going to make a difference—the fate of Eddie was truly in the Lord’s hands by then. But I bet you, none of that mattered to George Brown right then and there. You see, his involvement in this bizarre episode had nothing to do with country-bumpkin ignorance and superstition and everything to do with love and desperation. Then and now, love and desperation drive parents to do anything and everything to save their children. Is there a difference between George Brown, “vampire ashes” and the 19th century, and any number of 20th century parents who bankrupt themselves sending their dying wives and children to South America for treatment focused on peach pits or coffee enemas? I think not, and that’s the important fact that most folks telling the tale miss.

The desperate effort to save Eddie did not work. He died two months later.

The whole Brown clan is at eternal rest at the Chestnut Hill Baptist Church Cemetery in Exeter. Big George T. Cranston and Old Doc Metcalf share the green grass of Elm Grove Cemetery for all eternity as well. I visit them all on occasion and can’t help but think about the peculiar circumstances that caused their paths to intersect on that sad desperate day. So this Halloween season as you enjoy the spooky, mysterious festivities of this ancient pagan celebration day, don’t judge George Brown and his Exeter neighbors too harshly. Have fun with superstition and “things that go bump in the night,” but at the same time, don’t lose sight of the powerful connection of a father’s love. Rest easy, Eddie and Lena, and Happy Halloween to you all!

[Banner Image: Mercy Hill’s gravestone at Chestnut Hill Baptist Church Cemetery in Exeter, and the site of her exhumation in 1892 (Courtesy of Independent Newspapers)For further reading:

Abigail Tucker. “The Great Vampire Panic.” Smithsonian Magazine (Oct. 2012). Online version is at http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-great-new-england-vampire-panic-36482878/

Providence Journal, March 17, 1892