[Note from the Editor: The following interview appeared in “In the Wake of ’38, Oral history interviews with Rhode Island survivors and witnesses of the devastating hurricane of September 21, 1938.” The booklet of interviews was released in the Spring of 1977, and is available in some state libraries, including in South Kingstown. It was sponsored by the Rhode Island Committee for the Humanities and South Kingstown High School. The project directors were Linda Wood, then a librarian at the high school, and Judith Preble, then an English teacher at the school. Eleven South Kingstown High School students interviewed numerous eyewitnesses about the personal, social, economic, ecological and political effects of the Hurricane of 1938. The Editor encourages more high schools in the state to undertake oral history projects.

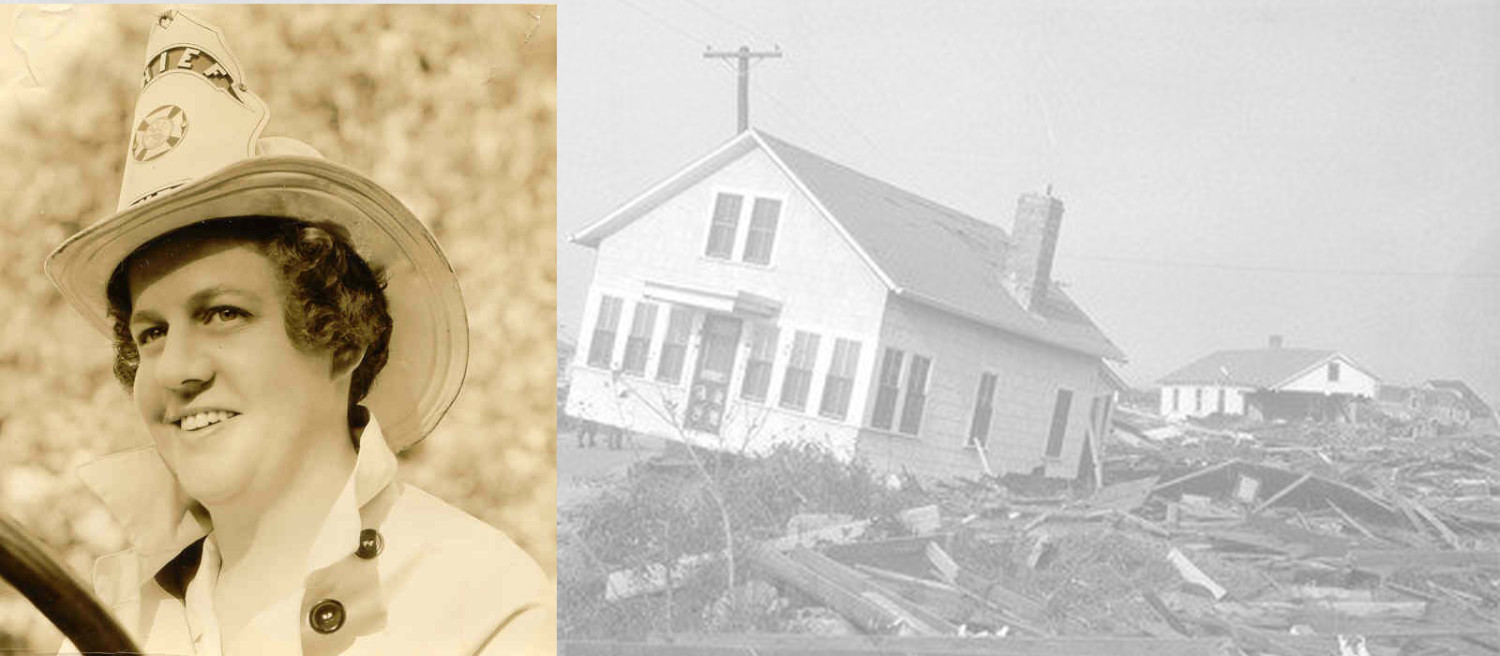

This is Part I of an interview with Ann Crawford “Nancy” Allen Holst (1908-1997), a feisty, clever and strong-willed woman who in 1938 was the State District Forest Fire Warden for Kent County. She was, according to one source, the first female fire chief in the nation. She was also one of only two female licensed pilots in the state in the early 1930s. As Nancy Allen Holst discussed below, in the immediate aftermath of the hurricane, she piloted her plane to spot dead bodies floating in the water so that they could be recovered.

Nancy Allen Holst was interviewed in 1977 by Jane Hutton, then a South Kingstown High School student (and former classmate of the Editor’s and a long-time friend). Part I addresses the impact of the hurricane that Holst saw. Part II, which will appear next week, will focus on the devastating impact the hurricane had on the state’s forests and timber industry.]

Mrs. Nancy Allen Holst, interviewed by Jane Hutton. April 27, 1977.

JH: Mrs. Holst, what was your occupation in 1938?

NH: I was the State District Forest Fire Warden for the Department of Agriculture and Conservation, Division of Forest Parks and Parkways.

JH: What is your occupation now? Are you retired?

NB: Why, I’m just an old farmer now.

JH: Where were you living during the Hurricane?

NH: Right in this house.

JH: How old were you when the Hurricane hit Rhode Island?

NH: I was 30 years old. I was born in 1908. Wouldn’t that make thirty?

JH: Where were you on the day of the Hurricane?

NH: Well, I was helping a couple of friends haul out their boats, because we were expecting a very high tide and some wind.

JH: Did the weather seem strange to you on the day of the storm?

NH: No. No. Not particularly. When the wind started to come up we realized that we were going to have something extraordinary.

JH: Could you describe the sky or the water? Was the sky ominous or anything like this?

NH: It was just a gray sky, but the taste of salt in the blowing rain was very unusual. It was so strong. You see, we’re way up the bay here; we’re not down on the ocean where you might expect to find such.

JH: Would you describe what happened to you on the day of the Hurricane?

NH: Well, that is a long story. We were trying to tie the vines, the ancient ivy on this house, up . . . . after I came back from the shore, the gardener asked my help. . . but we couldn’t get the ladder up, it was a sixty foot ladder and it was blowing. It blew out of our hands twice, so we gave that up. Then I noticed a car coming in. It was a friend of mine who’d gone to Apponaug to pick up his girlfriend, and he’d come down the Post Road and a tree had fallen in front of him. So he had turned off the Post Road and come up onto Love Lane, and another tree fell in front of him there. So he came down our driveway. He got in here and another tree went down behind him, so there he was trapped. So they came in the house and we all sat and watched the trees. They would go round like this, the evergreens would make a whole, full revolution and they’d break off. It had the definite whirl of a cyclone, more than a hurricane. That was right at the peak.

We never noticed an eye go over. It seemed to blow continuously. There was no lull in the middle.

JH: Do you remember what time that was?

NH: Four o’clock in the afternoon. Well, then it started to taper so we all got axes and went down the road and chopped our way out. I got out my fire truck and went to East Greenwich. By this time it was dark and East Greenwich was in complete darkness. I went to the fire station. Everybody was congregating there, not knowing what do. The wire chief from the telephone office next door came out when he saw my truck drive in. He said, “Oh, Nancy. Have got any portable juice?”

I said, “Sure, Mac. What’s the matter?”

“Well, we were caught with our pants down. Our batteries are flat and we are the only exchange through which Providence can get out. And our batteries are going to die very shortly and all communication that the city of Providence has will be lost.”

Nancy Allen Holst at the controls of a plane. She was one of the few female licensed pilots in Rhode Island in the 1930s and, piloting her plane after the 1938 Hurricane, she spotted dead bodies floating in the water so that they could be recovered. (Collection of Anne D. Holst and Clouds Hill Victorian House Museum)

Well, I said, “Jiminy, Mac. I can’t help you there because I’ve only got 110 volts.” But I immediately ran a line into the telephone exchange and gave him floodlights to light it. And I said, “I think I’ve got another generator out at the house that came off boats that’s a 32-volt. That’ll do you.” So I gave my crew orders to do whatever the East Greenwich chief wanted done and I came back to the house. Mac brought me out in a telephone truck with a couple of guys because this generator was very heavy and I couldn’t lift alone. We put it in and it went down in the back of the telephone exchange and it ran for 92 hours without ever shutting down and that’s the only thing that kept communication for the city of Providence open.

So that was a lot of fun. And that took the better part of well, it took until quite far after midnight, I can assure you. So then I came home, went to bed and I couldn’t sleep because all crossing bells on the railroad were shorted out and ding, ding, ding, all night. You couldn’t sleep. It was a terrible racket we had so many railroad crossings on this section of the New York-New Haven-Hartford Railroad. So, does that answer your question of w I was and what I was doing?

JH: I think so. Could you describe what you did after the Hurricane?

NH: Well, the next day I got a call from Providence Red Cross because I was, at that time, a First Aid Instructor, a life-saving instructor and captain of the Motor Corps. So I got a call from them to come in and give them a hand. The Red Cross disaster team, which is the national organization and goes around to disasters like hurricanes in Florida and other floods and things, had gone down to Florida because the Hurricane was supposed to come ashore down there. The Weather Bureau lost track of it and it landed up here instead. So they were delayed in getting here for about 24 hours and Providence wanted to know what was going on. So I said I’d serve as the liaison officer with South County, where the damage was the worst. After that I was on duty 24 hours a day for the Red Cross, running between Providence and South County.

JH: How did you get around?

NH: In my car.

JH: Were the roads travelable?

NH: Oh, yes. Most roads. Of course, there were trees across that you had to perhaps drive out in the field to get around or something like that. But you could get through. We had not had too bad weather. Before the Hurricane it had been wet, but it hadn’t been that wet and the ground was fairly good.

What did the Red Cross want? Well, they tried to answer all the requests that came in. Unfortunately, my most frequent request was for disinfectant or something to cut the smell in the morgues. It was really awful. Especially the morgue at Cross’s Mills. That was very pathetic. They took the brunt of the storm, I should say. They had tremendous loss of life there. Mr. Timothy Mee lost his entire family. He stayed there in the morgue. We couldn’t get him to leave. He viewed every body that came in, looking for some of his family. We couldn’t get them all. I finally had to go up to the airport and get my plane and fly over the pond because I found I could pick up quite a few bodies from the air.

JH: Did you just spot them and then radio someone else?

NH: Yes. The crew and the boats were down and I’d just come down over and hang a good zoom on the exact spot and they’d know where I was. You see, a lot of the people had on rubber boots and when they were fleeing or the storm hit them, then those rubber boots filled up with water and the weight caused the bodies to float that way. All you could see, was just barely the top of the head and it was impossible to see it from a boat. But I could see it from the air.

JH: Where were you flying when you were spotting these people?

NH: I did it over Charlestown Pond, ’cause that’s where they were having the most trouble.

Now, down in Westerly it was very sad because the Christ Episcopal Church ladies were having an outing at . . . what’s that hook of land that goes out from Watch Hill—I never can remember the name of it [Napatree Point]—into Little Narragansett Bay. Well, they were having this annual party in one of the summer houses and the whole neck was swept bare of houses so that the entire Ladies Auxiliary or Ladies Altar Guild—I don’t know what it was–they were all lost, except one who floated across Little Narragansett Bay on the roof of the garage and landed over in Connecticut.

. . . .

As far as I know, the only light–electric light–on the west side of Narragansett Bay the night of the hurricane was down in the East Greenwich telephone exchange and East Greenwich Fire Station being fed by the generator on my fire truck. I guess I was about the only fire department in Rhode Island that carried their own electricity at that time. You see, we fought forest fires all over the state and when you’re out in the woods you can’t expect to have the conveniences. So we simply had our own generator. Of course, it’s standard equipment on most fire trucks now.

. . . .

JH: Did you notice any cases of looting or stealing at the time of the hurricane?

NH: In Providence, yes. There was a great deal of it. I asked my parents what was the thing they remembered most about that first 24 hours of the hurricane. You see, mother had gone to Providence to get my father at the office. It had been so stormy that they had gone up to our city home at 12 Benevolent Street, and sort of holed up there to ride out the storm. She said all that night there was the worst din because all the parking lots with the cars had been submerged by the tidal wave and all the wires were shorted and all these automobile horns honked all night long. She said it was the worst racket you ever heard.

And that aside from the fact that the house was directly across from Beneficent Congregational is it? No, it’s the church on the corner of Benevolent and Benefit that has a beautiful slate roof. It’s a colonial church with a bell by Paul Revere in the steeple. The hurricane was blowing off these tiles, slate tiles, and they were coming right at our house and Mother was running around trying to get the inner shutters of this old colonial house shut to prevent these hurtling bombs coming through the windows. They had quite a time.

But I think that the looting was more or less restricted to Providence—that is, the serious looting. The areas down here were immediately closed off. The National Guard was mustered. Also you had to have a pass to enter shore areas. For instance, at Westerly on the Post Road, the road into Watch Hill was shut off, up above Dunn’s Corners and down below was pretty well-handled.

JH: Did you have a chance to get down by the beaches at all after the storm?

NH: Yes. I was very interested. Mostly I watched from the air to see how much washout there was. It was very interesting. It was also very interesting to see the tremendous power of the waves at Narragansett. I never figured that Narragansett Pier faced out to sea, but that sea wall and the road were just demolished.

You can understand how Charlestown would have gotten it because that certainly faces out to sea. My sense of direction must be off but it seems to me that Narragansett’s facing east more than south. The storm came out of the southeast.

JH: Was there great devastation on the beach?

NH: Yes, there was. There were piles an piles and piles of long ribbon seaweed. That was wonderful if anybody had had the time to pick it up to put on the fields. You know, the colonial people used it for fertilizer and I guess it was wonderful.

NH: Up on the South County Trail, just northeast across the road from the Bostitch Plant, there was a beautiful big barn on the Bourne Farm and that barn blew down with every cow in its stantion and every cow was killed. So there were many facets that you could only see by driving around that was not even to be covered by the press completely, because it was too vast.

. . . .

The tidal wave, I think, was the thing that most people didn’t notice, because if they were caught in it they were probably drowned or incapacitated in some way. In Charlestown Pond, that whole outer strip of land was all houses and they were all moved into the pond and blown across the pond and pile up on shore. There was one house that was absolutely intact. It wasn’t damaged in the slightest, even the windowpanes. And it was piled up on top of other houses. . . .

[Banner Image: Nancy Allen Holst, reportedly the nation’s first fire chief (Collection of Anne D. Holst and Clouds Hill Victorian House Museum)]

For further reading:

For a short summary of the remarkable career of Anne Crawford “Nancy” Allen Holst, go to the website for Clouds Hill Victorian Museum: http://www.cloudshill.org/chiefnancy.html

The Editor would like to thank Anne D. Holst, daughter of Nancy Allen Holst, for providing some information for the introduction to this article and for making available the images used in the article.