“Lost your marbles” and the directive to “knuckle down” are expressions that have found their way into our language from the game of marbles. These colloquialisms have endured in our vocabularies for a long time, but not as long as the game of marbles itself. William Bavin, author of The Pocket Book of Marbles, says “archoeologists have found game boards and playing pieces in the earliest excavated graves in Egypt and the Middle East.” The game was a popular form of entertainment with the Romans as well. They took it with them “to all parts of their empire.” J.A. Cuddon’s entry on “Marbles” found in The International Dictionary of Sports and Games claims that “it was the Romans who introduced marbles to Britain in the 1st Century. A.D. But it was to be nineteen centuries before it was organized as a competitive sport.” The British Marbles Board of Control was founded in 1926, “the same year British championships were instituted.” It is likely the notion of national marbles championships and champions gained momentum and popularity around the world from these early British efforts.

In centuries past, marbles were in fact made from marble, or sometimes stone or clay. Today, however, marbles are made from many different materials—glass being the most popular substance. According to the Pocket Book of Marbles, the reason for glass’s popularity is that it “lends itself to both hand and machine production and provides an article which is appealing to the eye and the touch.” Consider the aesthetic attraction of a marble called agate. Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary says agate’s beauty is the result of having its “colors arranged in stripes, blended in clouds or showing moss-like form.”

Fred Sturner, in What Did You Do When You Were A Kid? Pastimes from Past Times, recalls fond memories of marble games he played as a youth. Back then, “marbles came in all sizes, colors and were made of various elements.” Some of the sizes he discusses are KABOLAS, oversized marbles the size of jawbreaker bubblegum balls. Kabolas were made of glass in a kaleidoscope of colors. STEELIES or pinballs were extracted from the amusement arcade machines. JUMBOS were smaller than steelies and made of glass. The regular or average marbles measure about a half inch in diameter. And some smaller marbles called PEEWEES or MIBBIES. But where is all of this talk of variegated spheres leading?

Why back to Westerly, of course. It is Friday, May 15, 1931. Fill your senses with the sights and sounds and smells of an earth-aromad late spring afternoon. The days are longer and warmer. It has been a very polar winter. Just now the sun is dipping close to the horizon. The neighborhood kids are wending their ways home. They have been enjoying the after school hours outside playing games with their friends. They are not quiet about it. Their loud play-happy voices and the “baaang” of a kitchen’s screen door slamming against its frame boisterously proclaim their return home to be fed.

Suddenly, there on the kitchen table, one of them spies the Westerly Sun, folded, as if by chance, to reveal in very large headlines a story that would hold their interest for some time to come. Their curiosity was piqued by this lengthy bold print announcement “U.S. CHAMPION MAY LIVE HERE IN WESTERLY – MARBLE SHOOTERS WILL HAVE THEIR FIRST ELIMINATION SATURDAY – INTEREST SHOWN – BEST FIVE BOYS or GIRLS WILL GO TO PROVIDENCE NEXT WEEK.

Boys and girls all over town began to read the story under the headlines and dreamed and planned and wondered.

“The Palestine Temple, Mystic Shrine of Rhode Island, tomorrow at 2:30 p.m., will hold a play off to determine who the local marble champs are. Be at the High Street athletic field [Craig Field [1]]. All that is required of the kids was that they be under 15 years of age. The Shriners will provide the marbles.” (Not a bad idea what with kabolas and steelies in some contestants’ string-closed marble bags.) Their parents knew that it was all for a good cause. The Shriners were well known for their support of disabled children, just as Shriners are today respected for their concern for burn victims.

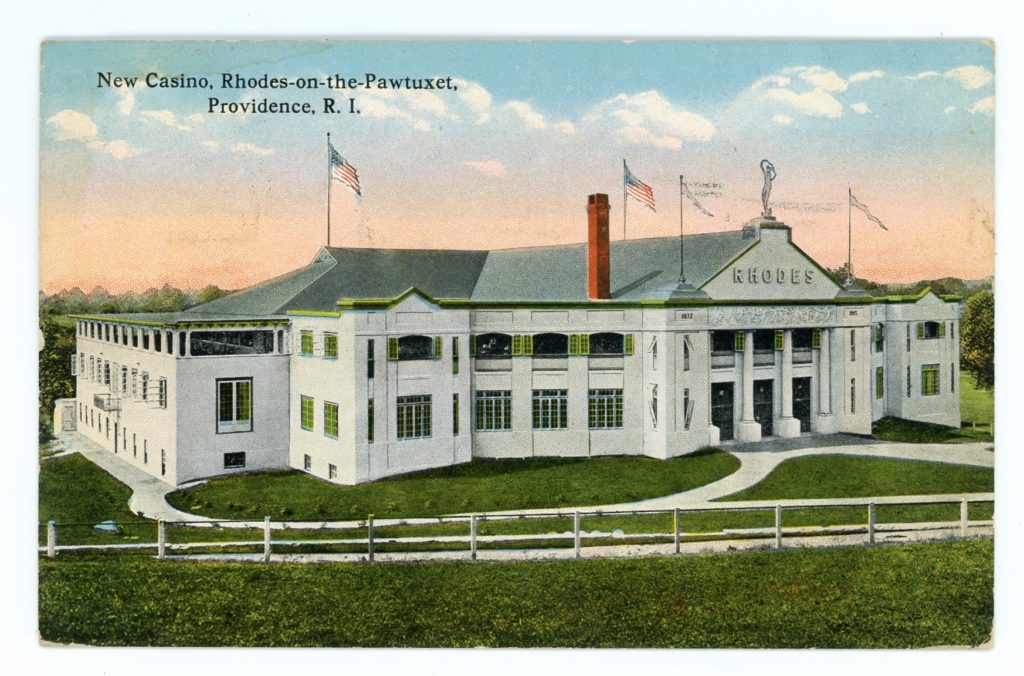

Medals were to be awarded to the five best finalists. In addition, the Westerly Sun reported, “the best five contestants will be given a chance to compete for the Southern New England Championship to be held at the Shrine Circus at Rhodes-on-the-Pawtuxet in Providence [really Cranston] next week.” What’s the catch? No catch. It was all free, for nothing.

It has been at least several generations since most school children have seriously played marbles. Manual dexterity today is measured by success with a Gameboy or other computerized games. This writer’s adolescence lacked an episode with marbles, so Fred Sturner will have to explain the game before this article continues. The game presented below is most likely the one Westerly kids played.

The second game we played with marbles was played on a patch of dirt between the sidewalk and the street. A circle was made about 12 to 15 inches in circumference. In it each kid placed five or six marbles. Then each kid in turn would shoot his marble by placing it between his thumb and forefinger and propelling the marble with a forward motion of his thumb. The idea was to use this one marble referred to as a shooter to knock as many marbles out of the circle and thereby keep those that you hit out for yourself, providing that the shooter itself did not get stuck in the circle. If yours was stuck in the circle you left it behind and you started from the original shooting line, which was usually six feet from the circle. Then again you went in turn, shooting your marble, trying to retrieve as many as you could. Sometimes you put a steelie in the middle, making it quite impossible to move out of the circle unless the shooter had another steelie. Of course, you always took the chance that someone could hit your steelie out and keep it. That was a catastrophe! If you knocked any marble out of the circle you would continue shooting until you missed, at which time the next person would go. When your turn came around again, you would shoot from the last place you landed. If your opponent yelled “knuckles down tight” before you could pick up your marble to shoot, you had to shoot while keeping your knuckles flat on the ground, and your fingers close together. Otherwise you could elevate your hand and shoot from any height you desired.

When the last marble was knocked out of the circle you would start over again, putting new marbles in, calling Larry to see who was first and so on down the line.

Early Saturday afternoon of the 16th, parents, relatives, pets, cars, trucks, and kids converged on the High Street Athletic Field. No doubt, there were more than a few wicker picnic baskets crammed with thick homemade sandwiches, fruit, baked goods, and cool drinks. It would appear that a large part of the town’s North End turned out to cheer their kids on.

Bringing order to this tumultuous event was John Farnsworth who “was in charge of the local tournament and much credit is due him for the fine manner in which he ran the tourney.” He skillfully arranged the 150 youngsters into five groups. Everyone quickly got into the spirit of things. Defeat meant elimination from the tournament. At the end of two hours the five winners were declared.

The boys who gained the title of champion were Everett Peduzzi, twelve years old, of 6 Haswell Street; Joseph Barboza, fourteen of Rose Avenue; Beppo Muntimuri, fourteen of 72 Pierce Street; Pasquale Iacoi, thirteen, of Marion Avenue; and Peter Wucik, fourteen, of John Street. The winners were presented silver medals and a fresh supply of marbles to practice with in preparation for the State Preliminaries at the Shriners Circus at Rhodes just three days later.

On Tuesday, May 19, two Westerly boys came through the Preliminaries unscathed. Beppo Muntimuri decisively defeated Vasso Polli of Pawtucket in only two games 9-4, 11-2. Pasquale Iacoi triumphed over Leo Spaziorio of North Providence 11-2, 13-0. The other three Westerly boys were not so fortunate. Joseph Barboza fell to Nesto Casorilli[2] of Providence 13-0, 13-0. Everett Peduzzi was bested by T. Rossi of Pawtucket 13-0, 9-4. Peter Wucik was narrowly defeated by Hector Marcotte of North Attleboro 8-5, 7-6.

Rhodes-on-the-Pawtuxet, the location of the marbles state championship, 1931 and 1932 (Sanford Neuschatz Collection)

Because of their successes on Thursday night, it looked as though one or two of the Westerly lads might have a berth in the State Finals. Although Beppo Muntimuri lost his first match with Nestore Cosovilli[2] of Providence 6-7, he came back to win the next two out of three games in that set 10-3, 9-4. Pasquale Iacoi had little difficulty eliminating Joseph Travers of Bristol, 10-3, 12-1.

As fate would have it, both Muntimuri and Iacoi were to lose in the quarterfinals on Saturday afternoon, May 23. The boys played valiantly forcing their opponents to best two out of three sets. Edmund La Rue of Bristol defeated Beppo Muntimuri 11-2, 3-10, 10-3. Westerly’s nemesis Hector Marcotte of North Attleboro had to deploy all his skills to roll by Pasquale Iacoi 6-7, 7-6, 7-6.

The Tournament Champ was Edmund LaRue, a student at St. Mary’s School in Bristol, who exclaimed, “Gee!” in excitement at the achievement. Judge Antonio Capotosto presented LaRue with his prizes at the first evening performance of the Shrine Circus. They included a gold medal, a silver cup both courtesy of the Palestine Shriners, and a complete outfit of clothes from the Outlet Company of Providence, as well as a trip to Ocean City, New Jersey, to participate in the National Matches.

************************************

It will be different this time, they thought. This year, 1932,the state championship was theirs. The Westerly boys had practiced and practiced. Their sore knuckles, some worn raw and bleeding, open wounds that could become dirt infected, would be worth the pain. Not alone did their discomfort result from lacerated finger joints, bruised knees, and aching necks, borne also was the loss of fun enjoyed playing other games with friends and neighbors. The whirring sound of a string-pulled top gyrating menacingly close to, colliding and disabling an opponent’s top somewhere on a smooth sidewalk or wooden porch floor; the satisfaction of seeing the piggy[3] become airborne to shoulder height, whacked so true and mightily that it sailed down the street as if winged; and, the speedy stealth and adrenalin pumping anticipation of discovery in a session of hide-and-seek – all these favored diversions dimmed in importance to the task ahead.

The prior year, 1931, that kid from Bristol, Edmund La Rue, had captured the Southern New England title at Rhodes-on-the-Pawtuxet in Cranston. He would be back, and Westerly’s Beppo Muntimuri and Pasquale Iacoi wanted to be back too. Their “flipping” skills could only be better this year and they were now tournament veterans. And Westerly had several other new players who were pretty darned good too.

The preceding year had been the first in which the Westerly youngsters engaged in the several levels of competition for the Southern New England Marble Shooters Championship. The event’s sponsor, again in 1932, was the Palestine Temple, Mystic Shrine of Rhode Island. The Shriners were seeking contestants, boys and girls, under the age of fifteen. So when the announcement of the year’s local matches was made in the April 29, 1932 edition of the Westerly Sun, Westerly’s candidates were ready. There were prizes to be awarded at the preliminaries on Saturday, May 7. The next level of competition would be held at the Shriner’s Circus at Rhodes-on-the-Pawtuxet. Only four from Westerly would make that important trip. The winner of the Rhodes contest would be sent to the National Matches in Ocean City, New Jersey, “later in the summer.”

The afternoon of April 30th, parents, kids, and well-wishers gathered on the High Street Athletic Field [Craig Field] to support the players. John H. Farnsworth again supervised the games. Carl E. Burdick, who worked for the Norwich Bulletin, was the official scorer. It is not known how many participated in that qualifying preliminary round. Victors on the 30th met again on Saturday, May 7, at the same location.

This time medals were awarded. The marbles champion of Westerly for 1932 was Louis Cappuccio, 14, of 88 ½ High Street. The May 8, 1932, Westerly Sun reported that Cappuccio “was outstanding in the preliminaries last week [and] was equally good yesterday…he won every match he played.” His successes automatically qualified him to represent the town the following Saturday, May 14, at Rhodes.

Also securing a place on the team representing the town was the youngest boy entering the tournament, Henry Nardone, 9, of 8 Pierce Street. Rated as the number two boy on the squad, he was an exceptional performer who “lost only one match of the many he played.” Nardone even played with a painfully sore finger on the 7th.

Called a “Dark Horse” by a local sportswriter, Adam Celestino, 12, of 19 Pearl Street, became the third member of the team, “winning his way to the finals in a brilliant streak of shooting.”

The fourth member of the team was tournament veteran Pasquale Iacoi, 14, of 6 Marriott Avenue, “who displayed some of the accurate ‘flipping’ that carried him so far last year.”

Local tournament champions were presented silver medals and marble sets.

Farnsworth, the tournament supervisor, was “well satisfied” with the boys’ performances. He predicted Westerly’s state squad would “make trouble for the other town champions” the following week at Rhodes.

The Sunday Sun that May 15 gave the boys a foretaste of the competition they would face at the Shriner’s Circus during the week of May 16-21. The field would be large, with fifty-four school and sectional winners, including from Newport, Attleboro, and North Attleboro, as well as Westerly. “The finals will be played at 5 o’clock each afternoon in two specially constructed rings at Rhodes,” the Sun announced.

Boys in Providence in 1912 playing another child’s game, pitching pennies (Lewis Hine, Library of Congress)

When Westerly’s best entered the lists at Rhodes in the afternoon of May 16, it was a time of high expectations for Westerly’s best. First, they needed permission to leave their high school, on West Broad Street, next to the Westerly Public Library, early. A ninth grader at the time, Louis Cappuccio, recalled that with their parents’ consent, he and the other high school students were excused early from school by the principal, Charles E. “Bull Dog” Mason. Mr. Cappuccio further remembered that the team was conveyed to Rhodes in the taxi of Mr. Joseph Pickering of 20 ½ Main Street. Mr. Pickering stood by and cheered as the Westerly boys played that afternoon.

The results of that first day’s round of Rhodes competition were splashed across the lower part of page one of the Sun for the Thursday, May 18 edition: “LOCAL MARBLE PLAYERS WIN EARLY MATCHES OF STATE MEET.” One of the glory boys was Louis Cappuccio who quashed John Kenney of Newport 11-2, 7-6. Adam Celestino easily quelled Thomas Warburton of North Attleboro 11-2, 7-6. “Showing good form and ability [again] this year,” Pasquale Iacoi extinguished the hopes of Chester Budjinski of North Attleboro, 8-5, 9-4. Westerly’s youngest team member did not, however, fare as well. Henry Nardone fell before the strength of Thomas Williams of Pawtucket 13-0, 7-6. It was expected that despite the loss of Nardone’s able flipping, the three remaining Westerly team members would excel in the next round of play. In any event, the Shriners fed the boys a good meal and sent them home. Mr. Pickering chauffeured an elated threesome home that evening, as well as the disappointed young Nardone.

Thursday’s games produced mixed results for Westerly. Louis Cappuccio, Westerly’s number one seed, fell before the onslaught of Edmund LaRue of Bristol, the prior year’s State Champion. Cappuccio made LaRue labor strenuously for the victory. ”With one game apiece Cappuccio having taken the first, 9-4, and LaRue the second, 7-6, the former champion knuckled down and with smooth shooting form captured the third game, 9-4.” Adam Celestino and Pasquale Iacoi fared better. Celestino convincingly beat Albert Blais of Woonsocket 7-6, 9-4, while Iacoi bested Chepe Pena of Newport 7-6, 9-4. Their victories moved them into the Friday semi-finals. The winners of Friday’s contests would then have a final go at the State Championship on Saturday.

The Sun did not publish on Saturdays back then, so most of the townsfolk had to wait for the Sunday, May 22 edition to find out what happened to their finalists on those two final days. It was not good news. On Friday afternoon both Celestino and Pasquale were defeated and thereby eliminated from the tournament.

“Defeated but not disgraced,” the Sun’s sportswriter proclaimed. Both youths battled mightily. Celestino, who had claimed victory in the quarterfinals in a comeback win by defeating Joseph Dill of Woodlawn 3-10, 8-5, and 7-6, was eliminated in the semi-finals.

The article failed to report how this befell Celestino. Interest instead fell on the odd conclusion to Iacoi’s brief career. He had jostled his way into the quarterfinals by overthrowing Edward Skrizmiarz of Pawtucket 9-4, 11-2. The unusual circumstances of his defeat occurred in the semi-finals when Iacoi was matched with one William Kenney. In their set of three games, Kenney won the first 10-3, “but Iacoi came back to tie the count with a 7 to 6 victory.” In the last game both boys were down to six marbles each. Then it happened. “Kenney shot at the last one and the agate smashed to bits.” The judges were in a quandary of what to do. This agate smashing, though always possible when using glass marbles, had not happened before. “Finally they decided to put another marble in the ring and the boys lagged for the first shot.” Pasquale went first. He saw how much rode on this flip. Perhaps he was really nervous. Whatever the reason, he missed his shot. Kenney knelt down at the ring’s edge, took careful aim, fired his shot, and knocked his opponent’s marble out of the ring. His clutch single shot at that moment earned him a slot in the semi-finals. It must have been a long, quiet ride home to Westerly that fateful Friday night for Celestino and Pasquale.

Could this great team from Westerly have won? Maybe, but a fatalist would say it just was not to be. The young men gave their all, did their very best. Luck favored the upstaters. By the way, the Sun did not list the name of the new State Champion in the final article. Still, the final marbles story at the semi-finals was reported on the sports page. The sport had gained some respect.

[Banner image: Boys playing marbles, circa 1910]]

Notes:

[1] The name of the High Street Athletic Field was changed to Wallace Charles Craig Field in 1934. Craig, a 1916 graduate of Westerly High School, was the first Westerly young man to die in the service of his country in World War I. He served in the U.S. Navy.

[2] Nesto Casorilli and Nestore Cosovilli were most likely the same youth.

[3] A “piggy” was often times created from a discarded broom handle. Boys cut a five to six inch piece of wood from the handle. The ends of the cut piece were sanded to cause it to resemble a pickle. Thanks for this bit of playground lore to Joshua A. McClure, who recently retired after twenty seven years as pastor of the Pleasant Street Baptist Church.

Follow Up and Thanks

Thanks to Attorney Louis B. Cappuccio, Sr. for his first-hand knowledge of the facts. Mr. Cappuccio survived his 1932 loss. In fact, he claimed that it helped prepare him for a life in Westerly and state politics.

Joseph Celestino, who became Coach Leo Smith’s “Iron Man” of the 1934 Westerly High School football team, is owed thanks for his valuable insights for this article.

Henry Nardone went on to complete a successful career at the Electric Boat Company at Groton, Connecticut and even today recalls his exciting times at Rhodes-on-the-Pawtuxet.