The stock market crash of 1929 sent America into the throes of the Great Depression. The levels of unemployment and suffering among ordinary Americans were unlike anything that had ever happened in the country, including in Rhode Island. By 1932, the national unemployment rate rose to an astounding 25%. At the time there was virtually no social safety net to help those without money or food.

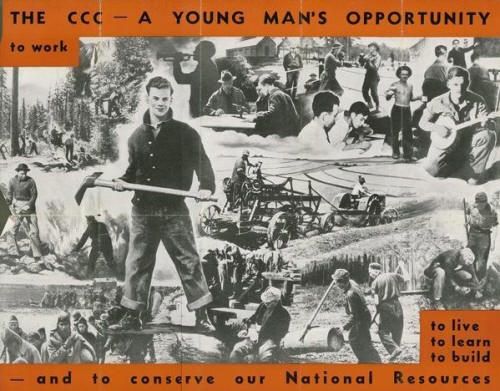

Americans looked for a savior in the 1932 presidential election race and found one in Franklin Roosevelt, who won the nomination of the Democratic Party. In his acceptance speech at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, Roosevelt alluded to a program he hoped to implement if elected: a conservation army for young men that would employ them, give them a sense of purpose, and help to alleviate the sufferings of their families. Most of the populace forgot about the promise, but after Roosevelt (also known as FDR) won the presidential election, and only forty-two days after being sworn into office, he ushered through Congress and signed into law the Emergency Conservation Act. This law created the Civilian Conservation Corps (the CCC).

Unlike the dark army of German Hitler Youth across the Atlantic, Roosevelt created a “Tree Army” manned by young men of America. Not only would they learn to work together, planting millions of trees, they would promote conservation. With their newfound paychecks, the CCC saved many of these young men and their families from starvation. A strong argument can be made that the young men of the CCC would become the foundation for the “Greatest Generation” during World War II.

The first open enrollment for the CCC occurred April 7, 1933. To allay union concerns over the program, FDR shrewdly appointed as CCC’s national director Robert Fechner, then vice president of the American Federation of Labor, and selected an advisory council of representatives from the Departments of Agriculture, Labor and the Interior. Responsibility for operating and building the CCC camps fell under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Army. Not surprisingly, the CCC would be run on a quasi-military basis. In Rhode Island, at the start, the secretary to the Rhode Island Unemployment Relief Commission, Henry T. Sampson, was ultimately in charge of the selection of Rhode Island enrollees.

To enroll in the CCC, the individual had to be a male, U.S. citizen, unmarried, physically fit, and unemployed. Many were selected from families on public relief. In total, some 15,900 Rhode Island young men enrolled with those qualifications. Nationally, a total of about 2.5 million men enrolled in the CCC. As the program matured the qualifications were modified so that 17-year olds could join and the maximum age limit was increased from age 26 to 28. Still later, married men could join as well. The program proved to be so popular that FDR, by executive order, enabled 25,000 World War I veterans to join regardless of their marital status, but they had their own special camps. Black men too were allowed to enroll, but were housed in segregated camps, due to the racial attitudes of the times.

Rhode Island young men were gathered at Fort Adams for training. Later, they were sent to a camp for two weeks at Fort Devens outside Worcester. There they went on hikes, performed calisthenics, played sports, and did some minor manual labor. All the while, Army drill sergeants evaluated each enrollee’s ability to work and follow regulations. At the conclusion of those two weeks, the young men received a final physical and inoculations for typhoid, paratyphoid and smallpox. From there the men were issued a uniform and took the CCC oath.

At first, the young men were housed in tents in camps until they constructed their own barracks. Nationally, there were 4,500 camps in the forty-eight states and the U.S. territories.

Rhode Island had eight camps, although they were not operated simultaneously or continuously. They were (with their official designations):

P 55, Foster, Providence County

S 51, Charlestown, Washington County [Burlingame]

S 52, Glocester, Providence County [George Washington Memorial State Forest]

S 53, West Greenwich [Nooseneck Hills; Stepstone Falls]

S 54, Hope Valley [Arcadia]

NP 1, Escoheag, Washington County [West Greenwich]

SP 1 (later NP-1), Beach Pond State Park [Exeter]

P 56 North Smithfield, Providence County [Primrose, Black Plain Road]

Fort Adams in Newport, the U.S. Army headquarters in Rhode Island, also served as the headquarters for the CCC in the state and in southeastern Massachusetts (encompassing the Fourth District in New England).

The typical camp included a mess hall, bath house, officers’ quarters, a recreation hall that usually housed the canteen, and barracks, each housing on average forty-five to fifty young men. The CCC enrollees led a structured life with a quasi-military routine. Reveille started the day, after which the sleepy men formed for inspection of their barracks. Then they marched, often two-by-two, in uniform for their breakfast. Dinner was more formal, held in dress uniforms; black ties were their meal ticket. Due to their malnutrition, their food portions were five percent more than those of the soldiers in the regular U.S. Army. The enlistees were sometimes so malnourished that they gained an average of twelve pounds each.

Enlistment was for a period of just six months but enrollees could re-enlist up to a total service period of two years, after which they were discharged. After a short absence, a discharged man could start the process all over again, and some did just that.

The pay was good, at $30 per month, but the enlistee was required to send $25 of those dollars home to his family. The money sent home saved many families from serious malnutrition and possibly starvation and kept them together. An estimated 12 to 15 million family members were supported in this way.

Being run by the Army during the fascist era of the 1930s could have been a sensitive issue so there was no drilling, no saluting, or weapons training, but there was forming into ranks, living in tents (at least until they erected barracks), and sometimes even having buglers. Many camps had two movies a week using state-of-the-art movie projectors, chaplain services, lending libraries, sports equipment, and vocational education.

Roosevelt mandated that all of the enlistees should be literate. Nationally, an estimated 400,000 illiterate enrollees became readers. A total of 603 different courses were taught in camps nationwide. Among the courses were practical vocational skills such as truck driving, heavy equipment operation, welding, typing, carpentry, stone cutting, motor mechanics, radio broadcasting, woodworking, cabinet making, metalcraft, and leathercraft. There were also courses in social courtesy and first aid.

Camps often had camp newspapers such as Rhode Island’s Burlingame Beacon, Escoheagan and Sad Day (the latter was at Fort Adams). These afforded opportunities to practice writing and engage in newspaper production. The newspapers often carried cartoons offering aspiring artists an opportunity to practice their skills. The men also composed songs, wrote poetry, and put on plays. They fielded baseball, basketball, horse shoes, and soccer teams that played other camps and teams in the surrounding communities.. Rhode Island’s Arcadia camp team won the soccer championship in the Southern league in 1936.

The men celebrated holidays in camp, including Mother’s Day. In one instance a commanding officer came around to collect 25 cents from each man to buy a pillowcase to be sent home to his mother as a gift. In another instance in Rhode Island, according to Boyden-Reynolds, the Rhode Island boys invited their mothers to camp for dinner and a skit.

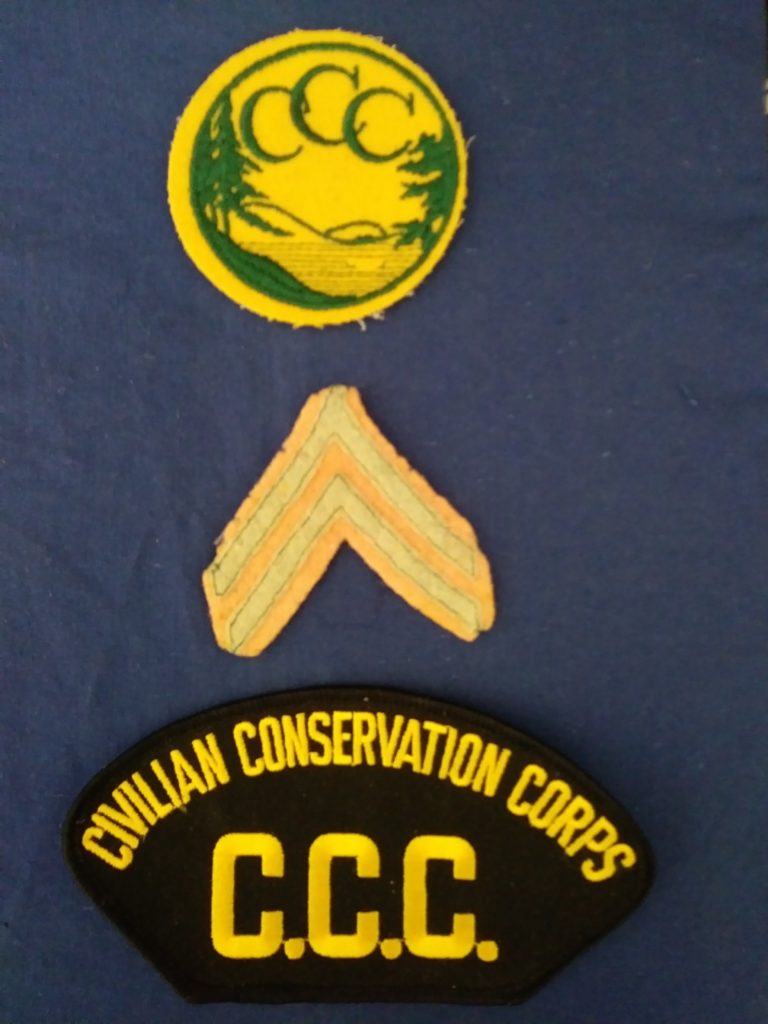

The enlistees wore olive drab Army surplus World War I uniforms, with black ties. They were given two pairs of shoes, more than some of them ever had, woolen pants, coats and khaki shirts. If a man was promoted, chevrons were added to the shirts similar to those of corporals and sergeants in the regular army. Some were selected to serve as leaders in work groups, giving them the opportunity to gain leadership experience.

At the work site, Army command of the young men was relinquished to another authority. Sometimes it was the park service or other managing body. LEMs (local experienced men) were frequently were put in charge of the work project. The enrollees served as carpenters, stone masons or whatever the particular job demanded. With the assistance of LEMs serving as their teachers, they learned new vocational skills, making them more employable upon their discharge. Their typical workday started at 7:15 a.m. and it was lights out at 10 p.m.

In April 1933, the first enrollees began arriving at Fort Adams. By May, 700 young men were in training at Fort Adams and their supervisors praised their morale and enthusiasm. The young men even held a “minstrel show,” with an orchestra, several trios of singers, and the following acts: hillbilly lumber jacks, clog dancer, muscular acrobat, tap dancer, harmonica trio, musical spoons, and a contortionist.

In late May, the first 189 CCC “forest men,” from the 141st Company, were sent to Burlingame Reservation in Charlestown. Soon the 142nd Company was formed and sent to the George Washington Memorial State Forest near Chepachet, and in June the 195th Company was sent to Nooseneck Hill in West Greenwich.

The 141st Company of the CCC in July 1935 at Westerly (probably at Burlingame Reservation) (Leo Caisse Collection)

Replacements continued to pour in. They were received and inspected for a physical examination at the army’s recruiting station at the federal building in Providence and then sent to Fort Adams. Each town had its quota. For example, Newport had a quota of 28 men, Tiverton 5, Middletown 4, and Jamestown 3.

In 1935, it was found that of 752 recruits received at Fort Adams between June 18 and July 15, 90 had completed high school and of them 6 had attended college, with none graduating. The commentators thought it was impressive that more than half had at least competed the seventh grade. By July 1935, a small group of CCC men had been at Beach Pond in Exeter preparing it for the arrival of the rest of the 1186th Company by building tents with wooden floors until the barracks could be completed. The men went in buses as far as Greene in Coventry, and from there CCC trucks conveyed them the remaining distance to the camp at the Connecticut-Rhode Island border.

In 1936, the sixteen CCC camps in Rhode Island and southeastern Massachusetts were connected to headquarters at Fort Adams using “ultra wave” radio stations, portable substations, and public address systems.

From April 1933 to June 1938, a total of 11,744 Rhode Island men served in CCC camps. Of this number, 11,121 were enrollees, including “juniors” and veterans, and 623 were LEMs, cooks and stewards. On October 20, 1938, 1,655 Rhode Islanders were serving in the CCC, with half working in Rhode Island camps.

In Rhode Island, CCC men built the following:

- Roadside picnic groves for travelers to rest and eat as they drove to and from beaches on the southern coast. Some of these roadside groves lasted through the 1960s and the advent of the interstate highway system.

- A camp for underprivileged children on Beach Pond in Exeter.

- Log cabin welcome/visitor centers at some of the state’s borders in honor of Rhode Island’s 300th anniversary.

- Over one hundred miles of truck trails to serve as access roads into the forest to aid in firefighting; many ended up doubling as back-trail scenic roads.

- Many fireplaces and trails, including in Goddard Park and Lincoln Woods.

- Beachfront (including fireplaces) on Bullock’s Cove in Haines Park in Barrington.

- Beachfront at Burlingame State Park, including the Beach Pavilion

- Parts of Burlingame State Park, Arcadia, Dawley State Park, and Step Stone Falls.

- Hiking shelters, at least one of which is still standing today after being rebuilt. It is located in the Arcadia Management Area almost at the intersection of Escoheag Hill Road and Plain Road.

- Innumerable wells/pump houses, water fountains, trailside grills, and fire towers.

Occasionally other federal agencies performed work in the forests. In 1938, for example, under the auspices of the National Park Service, Works Project Administration workers constructed buildings at Beach Pond Camp at Escoheag in West Greenwich.

The Hurricane of 1938 not only damaged the coastline, but was incredibly destructive of Rhode Island’s forests. CCC men helped with the clean-up operations, and conducted search and rescue and salvage operations. They harvested the fallen timber and even built saw mills to process the lumber and put it into storage areas. This same lumber was used to build military installations in Rhode Island and all over New England when the war came.

The CCC built this bridge from Haines Park in Barrington to Crescent Park in Riverside. It collapsed in the Hurricane of 1938.

In Exeter, the CCC men built the Volunteer Trail, the Rockville Trail, the Grassy Pond Trail, the Teft Hill Trail, and the Sessions Hopkins Trail. The Rockville Trail today is one of the best hiking trails in the state.

At the Rhode Island State Nursery enrollees helped grow forest tree seedlings.

By 1936, over a hundred miles of the one lane dirt truck roads cut through Rhode Island’s forests. While intended initially to assist in fire-fighting, inadvertently they created beautiful wilderness touring trails. According to a 1935 Providence Journal article, weekend motorists out for a spin, hoping for views of babbling brooks and small waterfalls, might expect to run into another automobile coming in the opposite direction. Many trails continue to be used for horseback riding. For example, about twenty-five miles of these unpaved roads of yesteryear can still be found along the Putnam Pike near the village of Chepachet in Glocester, Rhode Island, where the CCC had a camp in the George Washington Memorial State Forest.

The CCC built this beach pavilion around 1935, still standing at Burlingame State Park (Christian McBurney)

These back-country truck roads were also in Charlestown around Watchaug Pond at what would become Burlingame State Park. Roads were built, and often later became hiking trails, in Wickaboxet State Forest, the Diney Keach Trail, Brandy Brook, Richardson Clearing Trails, the Border Trail crossing into Connecticut and back again into Rhode Island, the Voluntown trail, the Rockville Trail, Grassy Pond Trail, Teft Hill Trail, Sessions Hopkins Trail, and the Durfee Hill Trail. About 186 miles of trails had been built but only about 100 miles were open to the public. These were unpaved roads that a car or fire truck could travel down. Some had been abandoned town roads which had been upgraded. Others were on private land to which the owners had granted the Federal and state governments unlimited access. Some private owners gated or otherwise blocked access to the roads. Today, the ones that remain are hiking trails and motor vehicles are not permitted on them.

Close-up of wooden beams and fireplace by the CCC at a beach pavilion at Burlingame State Park (Christian McBurney)

As of 2017, the CCC-built roads, according to the Department of Environmental Management’s Division of Parks, still exist and remain open to the public in the Pulaski State Park within the George Washington Management Areas in Glocester. The Olney Keach Trail runs North-South from Jackson Schoolhouse Road to Route 44 and Richardson Trail runs East-West from Olney Keach to Center Trail. While they are open to the public, they are now very rough and require four-wheel vehicles to use them unless on foot or horseback. The road at Burlingame is closed to vehicle traffic.

The Hannah Robinson Tower, a well-known landmark at the intersection of U.S. Route 1 and Route 138 at MacSparran Hill. Many think it was built by the CCC, but it was actually constructed by the Rhode Island Department of Public Works/Division of Roads and Bridges as a fire tower in 1938, and was rebuilt using the same pillars in 1988. When the tower was built, a viewer who climbed to the top could clearly see a broad valley and Newport below, but the trees grew and today they obscure the view.

One of many fireplaces built by the CCC at Rhode Island parks and road stops, this one is still at Haines Park, Barrington (Leo Caisse)

A picnic pavilion built by the CCC on the Escoheag Trail in Exeter (in Arcadia Wildlife Management Area off Escoheag Hill Road) is used today to protect hikers from storms (Christian McBurney)

The selected corpsmen had to secure parental consent if they were under twenty-one. These boys, many from poverty-stricken families, began their journey from Fort Adams in Newport. They then boarded at Providence a state-of-the-art special train that included ten Pullman cars, four baggage cars equipped with kitchens, two cars carrying their equipment, and one hospital car staffed with a physician. The baggage/kitchen cars were stocked with enough food and wood for their six-day trek. They were led by twenty-six leaders and their assistants. The total cost of the trip per man to the federal government was $133.36. If a man’s enlistment expired while in the West, the government provided transportation home.

In Oregon, the Rhode Island boys were primarily involved in building and maintaining roads in privately owned forests. They built fire service guard stations at Walton, Greenleaf, and Alsea. They also built fire lookout towers, trails and shelters. The CCC’s 141st company was absorbed into and became the 2108st company of CCCs. Its campsite was at Triangle Lake near the town of Junction City.

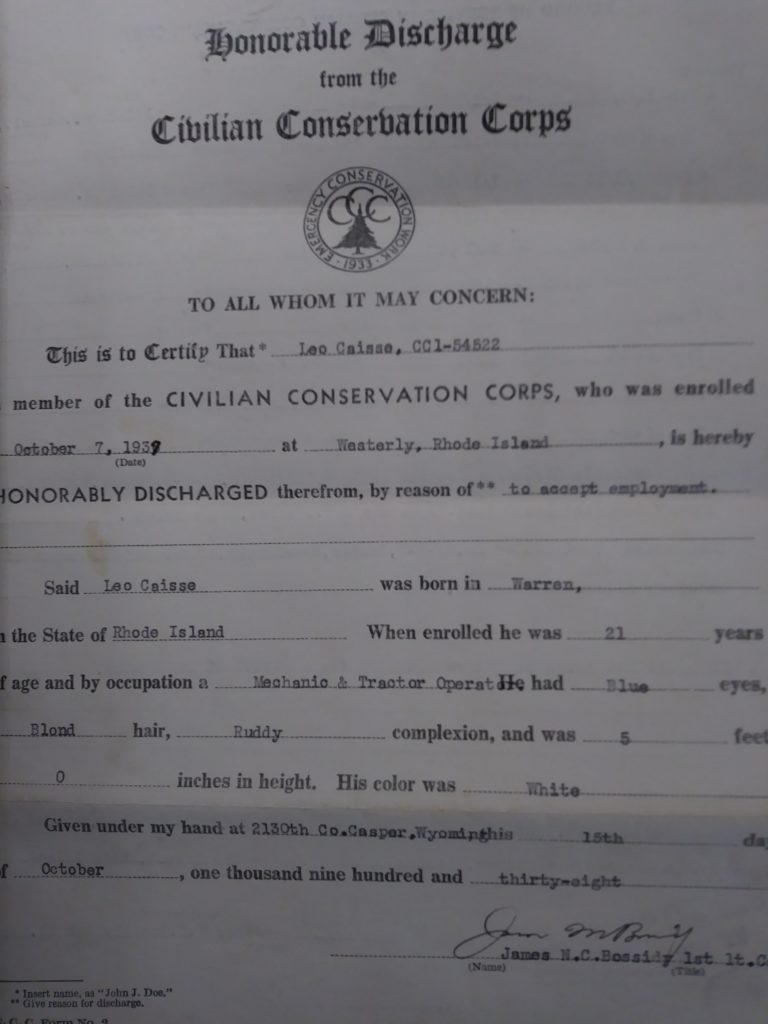

Here is the story of a Warren, Rhode Island, seventeen-year-old who joined the CCC on July 2, 1934. He was assigned to the 141st company of the CCC when headquartered at Burlingame in Charlestown. There the teenager learned to drive a truck, earning a license issued by the Department of the Interior.

At Burlingame, the teenager and other CCC enrollees engaged in work in both private and state-owned forests in Rhode Island. They built fire towers, truck roads for firefighting and logging, strung telephone lines, dug wells, worked on pest control and timber improvement, and built hiking trails, shelters and fireplaces. They helped develop a beach in front of the lake at Burlingame, which visitors can enjoy today.

In 1935, the 141st company, and another company from Rhode Island, were transferred to Oregon. The young man from Warren travelled with his company to Oregon, where he served the maximum four consecutive enlistments and was honorably discharged on June 23, 1936.

After a little more than a year off, the enrollee from Warren re-enlisted in the CCC on September 7, 1937. This time he was sent to the 2130th company, then located in the state of Wyoming. According to the National Archives historian Eugene Morris, it is difficult to ascertain with any degree of certainty why he was ordered there. Perhaps there was a manpower shortage or a need for a particular set of skills he had developed in the CCC. He could now drive a truck, operate a bulldozer, tractor and jackhammer, and weld and set explosives for demolition purposes such as moving boulders or removing tree stumps. He also learned a new skill, how to evade mountain lions. In any event, the young man from Rhode Island fell in love with the Wyoming and tried to persuade his new bride several years later to move there, but she would have none of it.

The Casper Chamber of Commerce persuaded the National Park Service to send Civilian Conservation Corps men, including the 2130th company, to go to the Casper area in 1937. Some of the work performed by the CCC on Casper Mountain included, building bridges, improving roads and reducing fire hazards. At Fort Casper they built parking areas, access roads and a dike in the river.

I did not get to know the Warren teenager well, as he passed away unexpectedly at a young age, when I was only nine years-old. But I still recall being mesmerized by his stories. The teenager from Warren was my father, Leo Caisse. It has been a great source of pride to learn about his adventures and the environmental legacy he left in such far-flung places as Rhode Island, Oregon, and Wyoming.

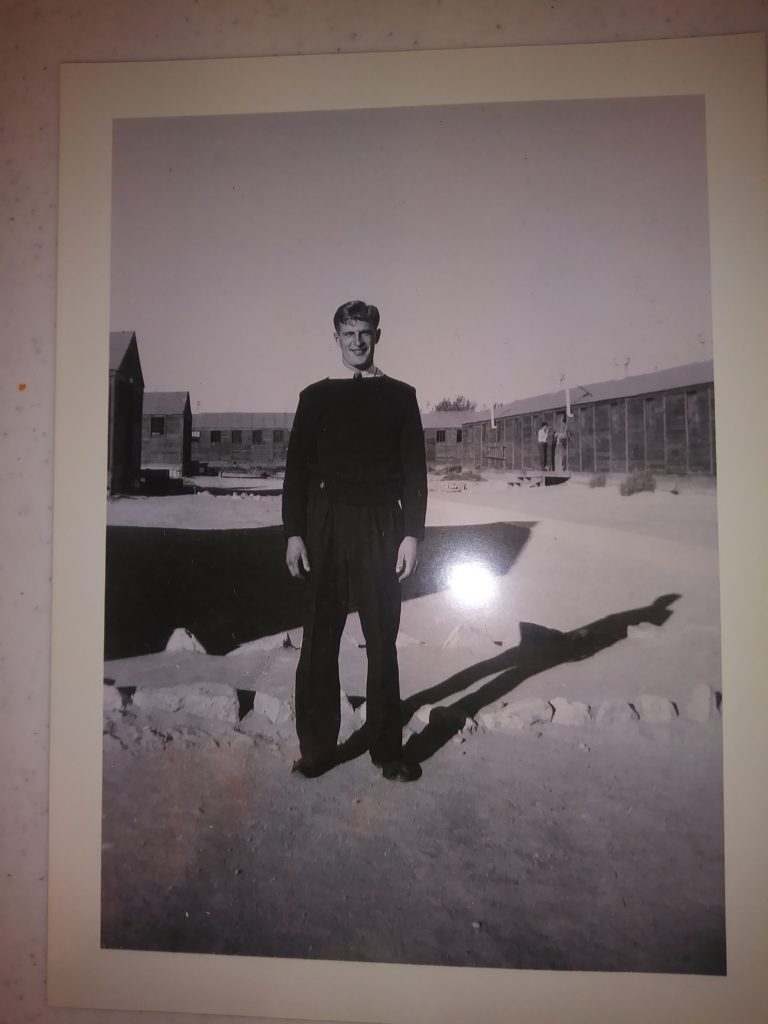

Leo Caisse, from Warren, Rhode Island, in the 2130th company of the CCC, in Wyoming in 1937 (Leo Caisse Collection)

By 1940 the dark clouds of world war loomed on the horizon. In the U.S., the draft began in September of that year, absorbing many of the eligible young men. The money allocated to the CCC was redirected to the War Department. Despite being a pet project of FDR and very popular with the public, the CCC was not funded by Congress in 1942, and it came to an end in June of that year. It never was a permanent agency.

The last two CCC camps in Rhode Island, after Arcadia was closed in 1940, were Beach Pond at Exeter and Burlingame State Park in Charlestown.

The young men from the CCC who were drafted or enlisted in the military took a pay cut. However, the U.S. Army recognized the value of CCC quasi-military training and frequently promoted CCC veterans to the rank of corporal or sergeant.

Ownership of CCC property often reverted to the War or Navy Departments. Such was the case at Burlingame State Park, where the Navy used former CCC barracks as overflow housing for pilots training at the nearby Charlestown Naval Auxiliary Air Field.

From time-to-time, calls to resurrect the CCC have been heard in the public arena. One such bill actually passed Congress in the 1980s but was vetoed by President Reagan.

In 1998, a report on Rhode Island forests prepared mainly by the U.S. Department of Agriculture stated that, “Within the next two decades, the trees planted by the Civilian Conservation Corps prior to World War II will be gone and almost all of Rhode Island’s forests will be the result of natural regeneration.”

Unfortunately, few structures built by the CCC remain. In 2017, in Dawley Memorial Park in Richmond, a one-story log shelter with a stone chimney built by the CCC around 1937 was torn down.

There is a small monument to the CCC, listing seven Rhode Island CCC camps, in the George Washington Management Area.

This has been the story of the Civilian Conservation Corps and what it accomplished in Rhode Island and nationally. The CCC helped our country’s forests and helped to spur interest in preserving and enjoying the environment. It also had a tremendous impact on the young men who enrolled in it. As one former CCC member said, these CCC boys took to the woods and came out men. The Tree Army conducted a peaceful occupation of Rhode Island forests and that of every other state; what they accomplished was staggering. Many of them carried on to serve in the military during World War II, perhaps our country’s finest contribution to the world.

[Banner image: A beach pavilion built by the CCC at Burlingame State Park, ca. 1935 (Christian McBurney)]

Bibliography

Rhode Island Sources

Al Klyberg, 100 Years of Rhode Island Parks, 2009

“Two Forestry Units to go to Camps in Oregon and Washington,” Providence Journal, October 24, 1935, p. 1

“Ten Car Pullman Train Starts West,” Providence Journal, October 26, 1935, p. 3

“100 Miles of Trails Built as aid to Firefighting,” Providence Journal, August 1, 1935, section, p. 3

Gary Boden and Sheila Reynolds-Booth, The Civilian Conservation Corps in Exeter, http://www.yorkerhill.com/eha/Stories/Civilian_Conservation_Corps_in_Exeter_RI.pdf

Newport Mercury, multiple issues, including April 28, 1933, p. 2; May 19, 1933, p. 7; May 26, 1933, p. 1; June 16, 1933, p. 2; June 30, 1933, p. 5; July 27, 1933, p.7; Sept. 28, 1934, p. 4; July 19, 19435, p. 2; Nov. 4, 1938, p. 1; and March 29, 1940, p. 9.

Rhode Island Secretary of State, http://sos.ri.gov/archon/?p=collections/controlcard&id=2887

Rhode Island Division of Parks and Recreation, http://riparks.com/

The Forests of Rhode Island. Prepared by the United States Department of Agriculture, U.S. Forest Service, Northeastern Research Station, in cooperation with the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management, Division of Forest Environment. Undated, but apparently issued in 1998. http://www.dem.ri.gov/programs/bnatres/forest/pdf/riforest.pdf

National Sources

John Hartt, Two Hands and a Shovel, 2013

William Lansing, Camps and Calluses, 2014

Stan Cohen, The Tree Army: A Pictorial History of the Civilian Conservation Corps 1933-1942, 1984

Jane McGrath, How the Civilian Conservation Corps Worked, https://money.howstuffworks.com/economics/volunteer/organizations/civilian-conservation-corp.htm

Phillip Rodman Moon, The Art of Manliness: The Civilian Conservation Corps Training a Generation in Manliness, https://www.artofmanliness.com/2010/01/07/the-civilian-conservation-corps-training-a-generation-in-manliness/

Acknowledgments for Assisting with this Article:

Kathy Marquis and Gary Brown, The Wyoming State Archives

Marion Caisse for reviewing drafts of this article

Catherine Cronk for her tireless online research

Douglas Cubbison, President, Wyoming State Historical Society

Michael Laferriere for his research on the Hannah Robinson Tower and Beach Pond Camp (WPA)

Christian McBurney, for his research in the Newport Mercury

Alan Maul, The Oregon Department of Forestry

Bill Mitchell, Director, Rhode Island Division of Parks and Recreation

Eugene Morris, National Archives, Records Section

Paul St. Pierre, Rhode Island Division of Parks and Recreation

Cheryl Roffe, The Lane County Museum, Lane County, Oregon