Occasionally taking rest breaks to play his violin or to sip tea in the stifling summer heat in Philadelphia, in 1776, Thomas Jefferson struggles to discover the precise mix of words to capture both the rationale and the emotion of the American rebellion. After presenting the fundamental parameters, he asserts: “The history of the present king of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having, in direct object, the establishment of an absolute tyranny over these States. To prove this, let facts be submitted to a candid world….”

Jefferson then unfurls a list of the many American grievances. After listing the first 24, he continues: “He is, at this time, transporting large armies of foreign mercenaries to complete the works of death, destruction, and tyranny, already begun, with circumstances of cruelty and perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the head of a civilized nation.”[1]

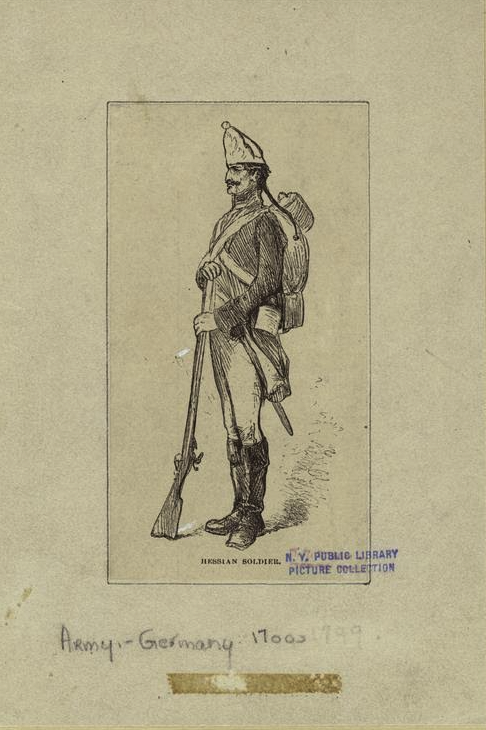

A drawing of a Hessian soldier, probably done in the late 19th century or early 20th century (New York Public Library Digital Collections)

This role of the “foreign mercenary”—despicable to the American mind in the late 18th century—came to be filled by German soldiers from the political sovereignties of the Holy Roman Empire, a loose federation of over 350 mostly German political entities united for centuries under one imperial umbrella.[2]

In the end approximately 30,000 German soldiers from six separate German principalities of the Holy Roman Empire played a key role during the six years that Great Britain attempted militarily to retain its American colonies, including the colony of Rhode Island. Historian Friederike Baer in her comprehensive study of German military participation in the American Revolutionary War, demonstrates that these forces served throughout North America, as well as Cuba, participating in all the significant military campaigns and in all the significant British victories and defeats.[3]

German troops also participated in the invasion and occupation of Newport and the rest of Aquidneck Island, as well as Jamestown (Conanicut Island) in early December 1776. Making up about half of the approximate 7,000 troops that occupied Aquidneck Island—called Rhode Island at the time—from December 1776 to October 1779, these soldiers served side by side with the British and Loyalist forces and performed similar military duties. In the American offensive military campaign during the summer of 1778, they helped the British army’s occupation force withstand the siege of Newport. On August 29, in the Battle of Rhode Island, they comprised one of the two main axes of advance, attacking the retreating American forces and launching three direct assaults on American defensive positions.[4]

The British Empire: Too Much Success?

As a result of the Seven Years War (1754-1763), Great Britain had achieved dominance over France in North America but also, with its far flung empire, had reached the point of imperial overstretch—too many possessions with too little military force to control and defend them. When the American Revolution was ignited, in April 1775, Great Britain had the greatest naval force in the world, but only 45,000 ground forces.[5] Of these forces, there were about 8,850 troops in North America—850 in Canada and 8,000 in the thirteen American colonies. Of these some 3,000 were in Boston under the command of General Thomas Gage, who believed at least 25,000 would be needed to quell the rebellion.[6]

In October 1775, King George III informed Parliament of his desire to “put a speedy End to these Disorders by the most decisive Exertions.”[7] One decisive military expedition against the American colonies, it was thought, would quell the revolt. This required a large military force, and given Britain’s overstretched resources, it could only be assembled by hiring foreign auxiliary forces.[8]

The British Search for Foreign Troops

The hiring of foreign troops was an accepted and common practice for major powers in 18th century Europe, one seen as legitimate according to the international law of the period. Not only Great Britain, but others powers such as France, Russia, and Prussia had hired foreign troops. During the late 17th century and throughout the 18th, Great Britain had fought many of its wars with foreign auxiliaries, and on many occasions these were German.[9]

It was not from the Holy Roman Empire that Great Britain first sought succor. In September 1775, it first asked Russia for 20,000 soldiers. Empress Catherine the Great declined. Russia had substantial commercial ties with the American colonies. Russia, she said, was still recovering from its recent war with the Ottomans, and the number of troops desired was too large and America too distant. The United Provinces of the Netherlands also declined.[10]

The British succeeded ultimately in signing subsidy agreements with six German rulers. While many of these rulers were reluctant to send their soldiers to another continent across the broad Atlantic, they were very eager to receive the sizable subsidy payments from Great Britain, revenues which in some cases were badly needed to balance the royal books.

The German troops who ultimately served on Aquidneck Island primarily came from two principalities whose rulers entered into subsidy agreements with Britain. The first was Frederick II, landgrave of Hessen-Kassel. He provided the largest contingent of troops of any of the rulers. Initially authorizing 12,000 soldiers to serve in America, by the end of the war perhaps as many as 20,000 ultimately fought in America. The second ruler was Karl Alexander, margrave of Ansbach-Bayreuth, who supplied some 2,500 soldiers.[11]

The Subsidy Agreements

The subsidy agreements or treaties set the conditions by which each German principality would provide a certain number of troops (with equipment) in exchange for subsidy payments from the British government. The troop units were to report to embarkation sites in the northern Holy Roman Empire (including parts of modern day Germany) and the Netherlands. After an inspection by a British officer, the soldiers were required to swear an oath of loyalty to the British king without renouncing their oaths to their respective German rulers. The German rulers agreed to supply additional recruits, as needed, to make up for losses.[12]

In exchange for these troops, rulers received annual subsidy payments, ranging from 22,500 Crowns for 600 troops from Anhalt-Zerbst to 450,000 Crowns for the 12,000 men from Hessen-Kassel. The individual German soldier also received pay equal to his British counterparts.[13]

In three of the treaties, there was the provision for what amounted to “blood money.” This indicated that the ruler would receive an additional payment for every three men wounded and each man killed.[14]

While troops from Hessen-Kassel and Hessen-Hanau comprised the majority of German soldiers in America and on Aquidneck Island, non-Hessian German troops also served in America and on the island. Both the British and the Americans generally just called all of them “Hessians,” something the non-Hessian troops did not appreciate.[15]

Overall, the German troops that came to America and so to Aquidneck Island were from a wide range of backgrounds and from areas both inside and outside of the two German principalities which signed the agreements. Some came from poor families; others, especially officers, came from upper class families.[16]

Eighteenth-century illustration of Hessian officer and private: Erste Officiers Unif. (first officer’s uniform) and Gemeiner (private)

They found themselves in America for various reasons. Some were certainly virtually forced to come by unscrupulous recruiters; others volunteered or came willingly for economic opportunity, to advance their officer careers, or perhaps to experience a genuine adventure. Some from the outset probably intended to remain in America.[17] Hundreds of thousands of Germans had already immigrated to America in the first part of the 18th century, most for economic reasons and many to avoid military conscription. In 1821 the famous German poet, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, reflected back to the year 1775 and said: “America used to be … the El Dorado of people who found themselves in a difficult situation.”[18]

Auxiliaries or Mercenaries?

The German soldiers who served in America were viewed and called different names depending on which side one stood. German subjects viewed them as fellow subjects marching off to war in dutiful obedience to their ruler. The British viewed them as auxiliary forces or allies. It is no surprise that Americans, unless Loyalist to the British Crown, viewed them as hated mercenaries. Historian Friederike Baer states: “Of all that Britain had done to violate the rights of the colonists, the hiring of foreigners was consistently depicted as the most cruel and despotic.”[19] In July 1776, shortly after the Declaration, Benjamin Franklin sought to explain the revolt to Lord Howe. In listing the grievances, he ended with, the British Government “is even now bringing foreign mercenaries to deluge our settlements with blood.”[20]

The American colonial view notwithstanding, the most appropriate term for these German soldiers is “auxiliaries” or “allies”, and not “mercenaries.” Mercenaries are individual soldiers of fortune motivated simply by financial gain. The German soldiers served, however, first out of duty to their rulers, who could withdraw them if, for example, the ruler faced a military emergency. Also, it was the rulers, and not they, who had signed the agreements.[21]

The Occupation Begins

On December 8, 1776, approximately 7,000 soldiers—about evenly split between British and German troops—came ashore unopposed on Aquidneck Island. The German troops were all from Hessen-Kassel.[22] Accompanying the soldiers was a large number of civilians, certainly a good portion of whom were their wives, most of whom also had hailed from Germany. For example, it was common practice for each British or Hessian regiment to bring along 50-80 wives who served as nurses and laundresses and fulfilled other roles in support of the army.[23] When the 620 troops from Bayreuth came in 1778, they had 29 wives with them—married men were allowed to bring their spouses.[24]

German chaplains Heinrich Kümmel and Johann Phillip Erb kept meticulous records, including recording several childbirths, baptisms, and infant deaths occurring at “Windmill Hill” in Portsmouth, at the north end of the island. (Americans called this Butts Hill.) This indicates that wives accompanied their husbands, even when they rotated from Newport to field assignments north of the city.[25]

In addition to wives, many Blacks—of Newport but also runaway enslaved men, women and even children from the Rhode Island mainland who came to Newport looking for employment and freedom—filled important roles for British and German troops. The British did not re-enslave the runaways; rather, they viewed them as a much-needed source of labor for such things as cutting hay and building fortifications and barracks. They also served as personal servants, waiters, launderers, and wagoners.[26]

Deployment and Duty on Aquidneck Island

The Hessian troops who came ashore on Aquidneck Island in December 1776, were not green; they had seen action already on Long Island and in the seizure of Manhattan. The joint British-Hessian forces quickly spread throughout the island, causing the estimated 600 rebel Americans to flee to the north towards Bristol Ferry and by small boats over to the mainland.[27] In a few weeks, the construction of earthworks began at Windmill (Butts) Hill in Portsmouth and Fogland Ferry. Units were assigned to winter quarters in Newport but also rotated to field positions outside of the city. Routine military operations began: fortification, guard duty, observation of enemy activity in Bristol and Tiverton, and countering minor raids by Americans. From the outset British and Hessian soldiers in the field near Common Fence Point had almost daily encounters with small raiding parties from Tiverton. British and Hessian troops were also deployed to Conanicut Island on the west side of the bay.[28]

Aside from their common military duties which they shared evenly with the British units, there was—being December—an urgent need for firewood, coal, and candles, a need which repeated itself every winter during the three-year occupation. When supplies of wood ran short on Aquidneck Island, sometimes hundreds of men were sent off the island for firewood to Conanicut Island but also as far as Shelter Island off Long Island. Because of the shortage, a rationing system was implemented which allotted quantities of wood according to rank.[29]

Perceptions: The German View of the Americans

The general view held by the German forces who came to America to aid the British was that the land was rich with natural beauty and resources and that the “rebels” had no basis for revolt. Being subjects of German principalities with fixed rulers, they were understandably conservative and critical of this upstart republic. Historian Brady J. Crytzer states that “the Germans’ worldview had shaped their opinions of the American revolutionaries. Rather than seeing …[them] as freedom fighters or defenders of liberty, the Germans saw them as opportunistic usurpers who threatened the modern social order.” [30]

Amazed by the apparent wealth and standard of living they saw, they could not grasp why Americans would want to rebel, to them a seemingly senseless undertaking. Perhaps Great Britain had been too indulgent, a view reflected in the diaries of some German officers.[31]

Regarding the rebel army, the widespread German view, certainly at the outset, was that it was not a worthy opponent. Germans criticized American fighters for being unshaven and unkempt, many dressed in rags, and employing strange and dishonorable tactics. Concerning the rebel officers, the Germans were likewise scornful. Most of these officers, at least from militia units, did not come from the American elite but were rather simple tradesmen, such as shoemakers, butchers, tailors, wig makers, and barbers.[32]

The Germans occupying Aquidneck Island generally held these same views. Because the rebels had risen against the British Crown, most thought they were wrong and worth fighting. At the outset the Germans believed the war would not last very long. By 1778, however, they realized that Americans were adamant in their commitment to their struggle.[33]

Captain Friedrich von der Malsburg, an officer in the von Ditfurth Regiment, served with the occupying forces for the entire duration of the occupation of Aquidneck Island and kept a diary. On December 19, 1776, a few weeks into the occupation, he states baldly: “The revolution is one of the most evil and sad circumstances.”[34]

Stephan Popp, a soldier in the Bayreuth Regiment, saw duty on the island beginning in July 1778. On his first day in Newport, he wrote, “Marched through the city and went into camp just beyond. The country [i.e., farmland] is poor, but the fishing is the great industry. There are many wealthy people, and the women are very handsome.”[35]

Each German regiment generally kept a journal, some of which exist today. On April 1, 1778, in the Journal of the von Huyn Regiment, is the following entry: “womenfolk are beautiful and witty … they have one fault: they side with the rebels.”[36]

Perceptions: The American View of the Germans

In general, the view held by American patriots—in contrast to loyalists—of the occupying German forces was one of hatred and contempt. Crytzer states that in the American mind, these Germans “were the very definition of ‘mercenary’”.[37] Historian Edward J. Lowell, writing in the 19th century, indicates that nothing could ever wipe out the shame of their cooperation with the British against the revolution.[38]

Unsurprisingly, lurid and ghastly stories of the Germans sometimes were exaggerated to the absurd. Lowell states that inhabitants of Shelter Island fled upon seeing the Germans, some believing that the Germans “ate up little children”.[39]

According to Baer, the American view was not one-sided. While they hated these German mercenaries for performing the king’s dirty work, they also had sympathy for the individual soldiers whom they viewed as simple pawns at the mercy of their tyrannical rulers. This explains American attempts to induce the Germans to desert.[40]

Concerning the view of Americans who remained on the Aquidneck Island during the occupation, they were understandably cautious and fearful of the Germans until familiarity increased. German soldiers had gained a bad reputation for brutality. American patriots sought to nurture fear and hatred of the enemy among fellow colonists. Evidently, the battle uniforms, bearing, and behavior of German soldiers could provoke trepidation. During the winters relations must have been strained as all parties competed for firewood with locals often blaming the Germans for shortages.[41]

German soldiers clearly plundered at times which did not help their image. In order to counter this and to promote trust among the colonists, Capt. Malsburg resolved early to prevent such plundering.{42]

By the end of the occupation after the Germans and American loyalists had become well acquainted, and the prior suspicions were found to be exaggerated on both sides. Lowell states that, “cordial feelings had grown up in the course of three years between the Hessians and the inhabitants of Newport.”[43]

Soldiering in Challenging Conditions

The conditions under which German soldiers served on Aquidneck Island during the three-year occupation were trying and sometimes lethal. They had to persevere through three very cold winters, with shortages of wood, provisions, and proper clothing.

During the first winter after their arrival in December 1776, many had to live in tents until better quarters could be found. They eventually occupied churches, houses, barns, and other buildings available throughout the island where they were deployed, with some cohabiting in homes with civilians {44]

Houses vacated by rebel families were used. Capt. Malsburg entry of December 14 explains: “Our regiment was assigned to 12-14 vacant houses. All that was there were the bare walls.”[45]

Fresh food and other provisions were in short supply with locals charging excessive prices until the military authorities established price controls. Troops in cases eventually had to make their own bread from spoiled flour, oats, peas, rice, and cornmeal. In his journal entry for October 29, 1778, Popp notes: “Went into winter quarters, in Newport, in old empty houses, very badly suited, and the food worse …of that not enough to thrive on and too much to die of starvation.”[46]

Unsurprising, the stressful conditions and malnutrition promoted disease. Baer notes that after that first winter, the troops suffered a high rate of disease, especially those related to vitamin C deficiency. By March, 1779, after the third winter, Popp reported that one-half of his Ansbach Regiment was sick with scorbutic diseases, with many dying.[47] Another Ansbach soldier, Wilhelm Philipp Ludwig Beuschel, recorded in his diary that 173 of the regiment suffered from scurvy.[48]

The three very cold winters took their toll as soldiers suffered and died from exposure. While the Germans arrived with woolen uniforms, these alone were no match for the winters they endured, especially the first one before resupply arrived.[49]

Upon arriving in December 1776, the Germans experienced a severe winter with high winds and heavy snowfall. The last winter was the worst and it turned lethal. On December 17 Popp wrote that after one terrific snowstorm the snow lay three to four feet deep. He added, “the cold was very severe, nine men of one of our regiments were frozen to death, twenty-three men had their hands and feet badly frost bitten. … Even the supply of drinking water was frozen.”[50] With stories of the lurid deaths, most of which occurred at guard posts in remote areas of Aquidneck Island, locals called it the Hessian storm.[51]

No matter how the quartermasters prepared, there never seemed to be enough firewood to service all the troops adequately. German and British soldiers alike, despite orders prohibiting them, eventually began tearing off planks of unoccupied houses, fences, and wharves, destroying them. When conditions became particularly dire, even church pews of confiscated churches were ripped out and burned as firewood.[52]

Inducing Desertion Among German Soldiers

The problem of desertion began even before German soldiers crossed the Atlantic. Once the subsidy agreements had been signed and recruitment begun, German authorities had to enact sometimes extreme measures to prevent the new recruits from absconding. Helping a deserter in the German city of Würtemburg, for example, could bring corporal punishment and hard labor. Sometimes recruiting officers were required to wear a sword, carry a pistol, and avoid large towns. Also, the recruit and the officer may have been required when lodging to undress and give their clothes to the landlord. Nonetheless, Lowell asserts “desertion was necessarily common.”[53]

The Continental Congress went to great lengths to induce German soldiers and officers to desert. By the time the first Germans soldiers had arrived in America, Congress had issued several proclamations directed at them. Written in German and published in newspapers in America and Europe, the first warned these Christian soldiers to consider Judgment Day when they would be called to account for oppressing Americans. It also promised them free land, no taxes for ten years, and all the rights and privileges of an American citizen. The second proclamation, among other things, clarified that the land grant would be 50 acres.[54]

Congress subsequently offered German officers grants of 100 to 1,000 acres, depending on their rank. The soldiers had to weigh these carrots against the punishments for desertion if they were caught. At a minimum, they would face flogging by being ordered to run repeatedly a gauntlet of German soldiers who beat them. However, some deserters were sent to death by hanging.[55]

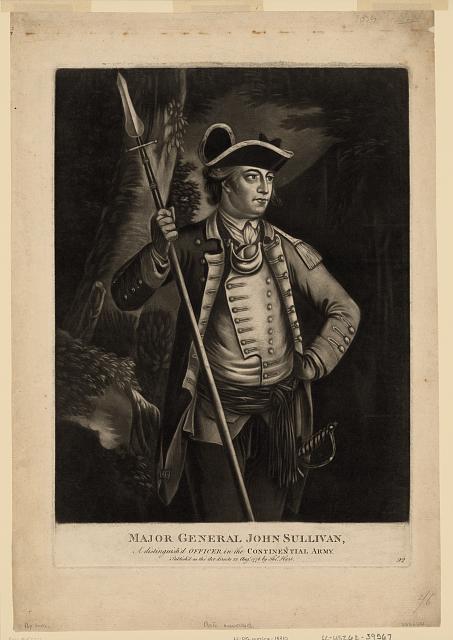

In August 1778, after the arrival of the French fleet off southern Rhode Island and a siege of Newport becoming imminent, there was a clear uptick in desertions on Aquidneck Island, more than in any other month of the occupation. After an American army under Major General John Sullivan landed on the northern part of the island, deserters could now find a haven by running to enemy lines, as opposed to having to take a boat. Historian Walter Schroder indicates that twelve deserted with two being recaptured. Popp’s Journal entry for August 11 states: “Many of the Ansbach Regiment deserted, rather than work hard ….” to improve the defensive works.[56]

Major General John Sullivan, commander of the American army during the Rhode Island Campaign (Library of Congress)

Significant Military Operations

Beyond fulfilling routine military duties and dealing with harassing raids from American forces, the German units occupying Aquidneck Island took part in two significant military operations over the three-year occupation: one minor and one major. The minor operation was a raid on the mainland north of Aquidneck Island on the towns of Warren and Bristol (and their vicinity). The major operation was the defense of Newport against the American offensive campaign leading to the Battle of Rhode Island on August 29, 1778.

By May 1778, British intelligence revealed the Americans, emboldened by their alliance with the French earlier in the year, were planning offensive operations in Rhode Island. Having learned of American military stores and flatboats assembled in Warren, Gen. Robert Pigot, the British commanding general, directed Lt. Col. John Campbell, with a combined force of 500 British and German soldiers, to conduct raids to burn the flatboats and march on Bristol and Warren. The German units included a company of chasseurs (light infantry), led by Capt. August Noltenius, and 125 soldiers from the von Huyn and von Bünau Regiments.[57]

The combined British and German force conducted raids on both Warren and then Bristol, burning ships, seizing and burning military stores, burning selected homes of patriots, churches, and stores of rebel sympathizers, plundering homes, and seizing adult men as prisoners of war. In Bristol, an Anglican church, mistakenly thought to have been used to store military supplies, was burned, and the fire spread to nearby homes, consuming them.[58]

One can glean a sense of the Hessian plundering from Warren historian Guy Fessenden, writing in the mid-19th century. According to Fessenden, “The Hessians wore enormous fur caps, and large, wide and loose boots, into which they thrust all kinds of articles pilfered from houses; and these articles, hanging over the tops of their boots, gave them a singularly grotesque appearance ….”[59]

The raids proved to be fruitful. The raiders burned 70 flatboats, destroyed numerous military supplies and weapons, spiked more than 40 cannon, burned some 40 houses and three public buildings, burned the row-galley Washington, and seized about 60 prisoners, most of them civilians. (Americans later lambasted Pigot for taking civilians prisoners, who were used to exchange for British army prisoners.) While the Americans counter-attacked late in the day, the raiders suffered just 15 wounded and two drummers captured.[60]

Major General Robert Pigot, commander of the British army during the Rhode Island Campaign. Portrait by Francis Cotes, circa 1765.

Countering the American Offensive Campaign

Alongside the British and Loyalist forces, German units took part in repelling the French-American campaign in July-August 1778, to retake Aquidneck Island and Newport. In the Battle of Rhode Island on August 29, it was a German unit of light infantry (known as chasseurs) that made the first contact and it was mainly German units which comprised one of two major axes of advance against the Americans. Moreover, it was evidently a German unit—the von Huyn Regiment—that sustained the most casualties of any regiment of the allied British force.

In mid-July, the British-German forces on Aquidneck Island were reinforced by German units stationed in New York City, including a regiment from Ansbach and one from Bayreuth (non-Hessian units). These units returned the occupying force to near its original strength—about 5750 troops.[61]

During this period on the American side, planning moved forward to retake the island and destroy or capture the occupying forces. Gen. George Washington appointed Maj. Gen. John Sullivan as the overall commander.[62]

American hopes were heightened when on July 29, the long-awaited French fleet arrived off Point Judith, the southern-most tip of western Rhode Island. Commanded by Admiral Jean Baptiste Charles Henri Hector, Comte d’Estaing, this fleet included eleven ships of the line (battleships), a 50-gun ship, and four frigates (light battleships). The force also included 4,000 French soldiers, sailors, and marines. The ships immediately deployed to block the three channels of Narragansett Bay. For the first time, the British navy no longer had command of the waters of Rhode Island.[63]

Preparing for the joint French-American attack, British Gen. Pigot deployed the British-German-Loyalist forces in two lines of defense north and east of Newport. The Ansbach, von Huyn, and Landgrave Regiments occupied the first (outer) line of defense. Some 200 soldiers from the von Ditfurth occupied Tonomy Hill (now Miantonomi) which anchored the left (western flank). Occupying the inner line were the Bayreuth, von Ditfurth, and von Bünau Regiments along with the two chasseur companies. On August 8, as the French forced their way up the middle channel into Narragansett Bay, all British allied forces withdrew behind these two defense lines.[64]

Having finally assembled a force of about 11,000 Continental, state, and militia troops from throughout New England, Gen. Sullivan finally ordered on August 9, the crossing of the Sakonnet River and the occupation of the northern part of the island, including the Butts Hill fortifications/barracks evacuated by the British allied forces. However, on the very same day, British Admiral Richard Howe arrived with his relief force of some 30 ships. Facing the difficult choice whether to remain in the bay or challenge the British force on the high seas, French Admiral d’Estaing choose the latter, much to the dismay of the Americans.[65]

As the Americans dealt with their feelings of betrayal and disappointment, Mother Nature stepped in to further complicate the operation. Referred to as the “Great Storm,” the two-day hurricane decimated both fleets which had been jockeying for the wind advantage in the Atlantic Ocean. One German soldier stated of the hurricane: “most of the tents were torn to pieces,” forcing the soldiers “to camp the whole time under the open heavens”…”cold and wet.”[66]

Admiral d’Estaing now faced a second decision. With his fleet in disarray and crippled, including his command ship, the Languedoc, should he stay and continue the joint operation with the Americans or depart to Boston for repairs? Reluctantly, he chose to depart, infuriating the Americans.[67]

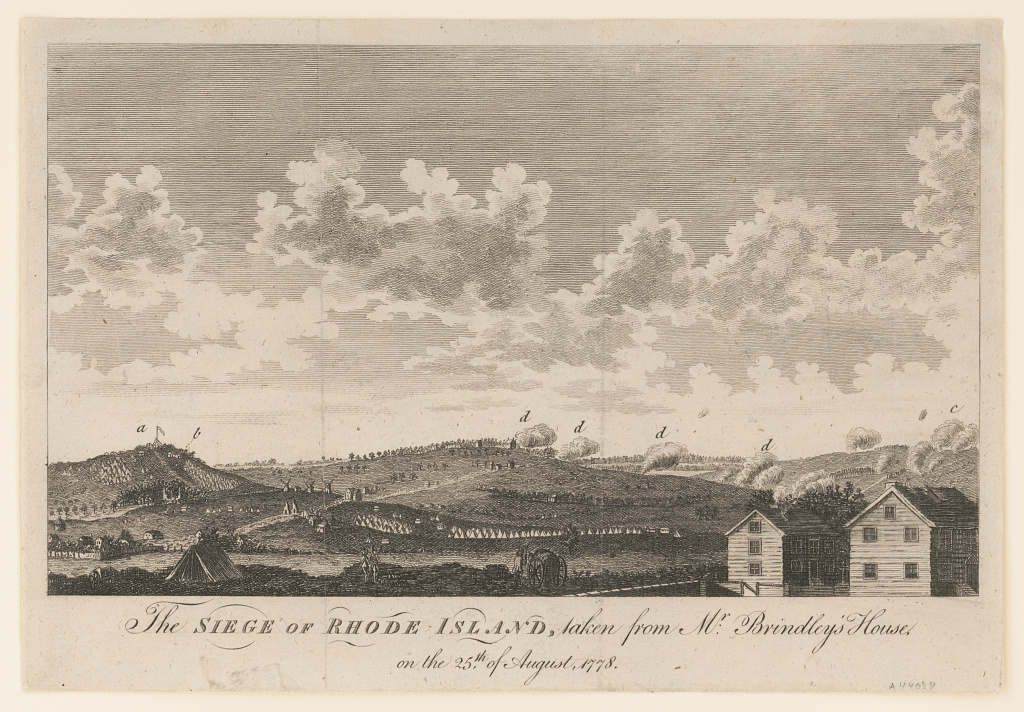

Despite the French departure, Gen. Sullivan decided to continue the offensive and lay siege to Newport. He was sustained by the expectation that the French fleet would in short order return. With close to 12,000 men—the most he would have under his command—American forces approached and encircled Newport, August 15-28. By August 28, the French fleet still had not returned, and Gen. Washington had informed Sullivan that a British relief force was on its way from New York. Moreover, because of the French absence, many volunteers had lost motivation and the short terms of many of the militia were expiring. They wanted to return to their farms and families. By August 28, his force had decreased to 7,800 troops. Holding a council of war with his senior officers, Sullivan decided to lift the siege and retreat.[68]

Comte d’Estaing, commander of the French forces during the Rhode Island Campaign. Portrait by Jean-Baptiste Lebrun, 1769.

The entry of the French squadron in Narragansett Bay, August 8, 1778. Drawing by Pierre Ozanne, 1778 (Library of Congress)

The Siege of Newport. (This drawing shows the siege of Newport in mid-August 1778, prior to the Battle of Rhode Island (Library of Congress)

The Battle of Rhode Island

With American forces in retreat, British Gen. Pigot sensed opportunity and ordered an attack with three axes of advance. The units comprising the western axis included Capt. Malsburg’s company of chasseur and the Ansbach and Bayreuth Regiments, with supporting artillery—about 1,000 troops—commanded by German Maj. Gen. Friedrich Wilhelm von Lossberg. At 7:00 am Malsburg’s unit made the first contact of all units. After hearing the musket fire, Gen. Pigot also deployed forward the von Huyn Regiment north on the West Road. Lossberg now had about 1,800 men which quickly compelled the American rearguard force of 300 troops to retreat.[69]

Pushing northward, the German axis of advance eventually seized Turkey Hill. Responding to action to his east, Lossberg deployed the von Huyn Regiment to flank the American rear guard fighting the British at Quaker Hill. Maj. Gen. Pigot kept three German units in reserve: the Landgrave, the von Ditfurth, and the von Bünau Regiments. As the battle lines hardened, the force strengths across the main lines of contact stood at 3,700 British, German and Loyalist soldiers facing some 3,900 Americans, not counting reserves.[70]

At mid-morning with fierce combat to the east on the East Road and at Quaker Hill ending in front of Butts Hill in stalemate, action now switched to the German (western) axis. Over the next several hours the Germans launched three assaults to break and turn the American right, the final led by Maj. Gen. Lossberg himself, all repelled by the American right-wing, led by Rhode Island’s own Brig. Gen. Nathanael Greene. This staunch defense included action by the 1st Rhode Island Regiment, known as the “Black Regiment,” since many of its soldiers had gained their freedom from slavery by enlisting in the regiment.[71]

In nine hours of combat that day, the American line held. This allowed, on the day after the battle, for the successful retreat and evacuation of American forces to Tiverton across what is now called the Sakonnet River. This evacuation was accomplished with no time to spare. On September 1, Gen. Henry Clinton arrived with 70-ships carrying 4,300 British troops, hoping (in vain) to trap the American army on Aquidneck Island.[72]

Regarding casualties, Gen. Pigot’s official report stated combined British, German, Loyalist casualties of 260 with 38 killed. Gen. Sullivan reported casualties of 211, with 30 killed.[73] The von Huyn Regiment evidently had the most casualties of any regiment of the British allied force—five killed in action and 57 wounded.[74]

Historian Christian McBurney states that tactically the battle was a draw. Neither commander wanted a full-scale battle. British Gen. Pigot was happy to push the American force off the island. He had no desire to risk his military force or Newport for a chance to gain a decisive victory. Gen. Sullivan was glad to successfully evacuate his force from the island before the British reinforcements arrived. On the other hand, McBurney adds, British army observers were impressed with the improved fighting of American soldiers.[75]

Strategically, most historians would call the entire Rhode Island campaign a win for the British who continued to hold Newport and the rest of Aquidneck Island as before.

Map of the positions occupied by the American troops around Rhode Island on August 30, 1778. By Michel Capitaine du Chesnoy, aide-de-camp of General Lafayette (Library of Congress)

The Final Year

During the final 14 months of the occupation after the Battle of Rhode Island, there were no further major engagements between the British allied forces and the Americans in Rhode Island. The two chasseur companies were disbanded on November 25, 1778, and the men were returned to their original regiments. In early June, the Landgrave Regiment was withdrawn from the island and served in New York City. The occupying force had to endure its third and final very cold winter with shortages of firewood and provisions, causing more deaths due to exposure.[76]

In the Fall of 1779, the British high command feared that a French fleet would again try to seize Newport. This time, the decision was made to evacuate Newport. On October 25, 1779, the remaining units of the garrison departed on a fleet of more than fifty ships. The von Ditfurth Regiment and a part of the von Huyn Regiment served further in Charleston, S.C., and the Ansbach-Bayreuth Regiments served in Virginia. By 1783, all German units had returned to their original European ports of embarkation.[77]

Conclusion

In London, in 1820, when the American writer Washington Irving was penning his haunting tale, “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” he knew he had a great yarn, but it lacked a great ghost. The role of the headless horseman he eventually filled with that brutal, plundering, benighted, and strange mercenary who fought against our sacred revolution and who still evoked terror in the American mind—the “Hessian.”[78]

We cannot be sure of the number of Germans serving on Aquidneck Island who chose to remain in America at war’s end. They likely numbered in the hundreds. However, we do know that of the 30,000 Germans who served in America, only 17,000—56%—returned to Europe. Of the 12,000 who did not return, about 7,500 died: 1,200 from combat and 6,300 from accident or disease.[79]

A very large number—about 4,500—chose to turn their backs on the Old World and their old lives and begin a new life in this new land of wilderness and danger, but also of beauty, liberty, and opportunity.

[Banner Image: Soldiers of the Leib Grenadier Regiment, which served in Newport. Note the Black drummer with a turban. Enslaved people in Newport, and those that escaped enslavement from the mainland, sometimes were employed by German regiments in Newport.]

Footnotes

[1] Two sources speak to this scene: Brady J. Crytzer, Hessians: Mercenaries, Rebels, and the War for British North America (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2015), xxiii; Friederike Baer, Hessians: German Soldiers in the American Revolutionary War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022), 22, 25. [2] Crytzer, Hessians, xvi; Baer, Hessians, 7. These included principalities, electorates, duchies, landgraviates, ecclesiastical territories, and free imperial cities, most with their own prince, court, and military forces. [3] Baer, Hessians, 2. [4] I dedicate this article to Heinrich & Thea Hill, who were my wife’s and my landlords in Mainz-Mombach, across the river from the state of Hesse, West Germany, in 1971-72, the first duty station of my military career. They showed us great kindness. Helping me patiently with my German, “Harry” had served as a private in the German Army in World War II. As the Germans were cold and hungry 250 years ago here in Rhode Island, he was hungry and cold for nine months on the Eastern Front before being captured in North Africa. He spent two years eating hot dogs and cheddar cheese, and constructing baseball diamonds at a prisoner-of-war camp in Texas. Harry und Thea, Ruhe in Frieden. [5] Crytzer, Hessians, xiv. [6] Ibid., xvi; Baer, Hessians, 6; Walter K. Schroder, The Hessian Occupation of Newport and Rhode Island, 1776-1779 (Westminster, MD: Heritage Books, 2009), 15. Schroder’s book squarely addresses the topic of this essay. In researching it, he traveled to Germany and viewed many primary documents. Regrettably, it is void of citations to the original sources. [7] Quoted in Baer, Hessians, 9. [8] Baer, Hessians, 10. For a discussion of the debate which ensued in Parliament, see Crytzer, Hessians, xxxi-xxiii, and Edward J. Lowell, The Hessians and the Other German Auxiliaries of Great Britain in the Revolutionary War (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1884), Chapter III, in In The Hessians plus The Voyage of the First Hessian Army and Popp’s Journal, 39-396 (Pierceton, IN: Townsends, nd). [9] Baer, Hessians, 6. [10] Ibid., 8-9; Crytzer, Hessians, xiii; Schroder, Hessian Occupation, 16. [11] Baer, Hessians, 12-13; Schroder, Hessian Occupation, 8. “Landgrave” was one of the titles for a sovereign German prince. “Margrave” was another such title for a German nobleman, which out-ranked a landgrave. [12] Baer, Hessians, 15-16. See also Lowell, Hessians, 14-16; Schroder, Hessian Occupation, 19-26. [13] Baer, Hessians, 16-17. See p. 31 for summative figures. Baer states it is clear Great Britain paid an enormous sum over the course of the war; however, the exact amount is impossible to calculate. [14] These three agreements were with Braunschweig, Hessen-Kassel, and Waldeck. Baer, Hessians, 16; Schroder, Hessian Occupation, 23. [15] Schroder, Hessian Occupation, 25. [16] Baer, Hessians, 61. [17] Ibid. [18] Quoted in Baer, Hessians, 54. [19] Baer, Hessians, 22. [20] Quoted in Baer, Hessians, 25. [21] I agree with Schroder’s analysis on this subject, see Hessian Occupation, 25-26. In contrast, Lowell, writing in 1884, consistently uses the term “mercenary.” Lowell, Hessians, 5, 6, 27. The term “mercenary” continues to be associated with these Germans. Zach Zorich, writing in the New York Times on August 8, 2022, called them “Hessian mercenary allies.” Zorich’s article is entitled, “’What a Horrible Place This Would Have Been.’” The term “mercenary” and the use of mercenaries is alive and well in world politics today. For example, see Benoit Faucon and Joe Parkinson, “Kremlin Leverages Mercenaries,” The Wall Street Journal, August 8, 2022. [22] Schroder, Hessian Occupation, 1, 8. For a general survey of this period, see Rockwell Stensrud, Newport, A Lively Experiment, 1939-1969 (London: D Giles Limited, 2015); Elaine Foreman Crane, A Dependent People: Newport, Rhode Island in the Revolutionary Era (New York: Fordham University Press, 1985). [23] Schroder, Hessian Occupation, 31. [24] Ibid., 53. Baer indicates that an estimated 100 servants and women accompanied the 1,300 troops from Ansbach-Bayreuth in the spring 1777. Baer, Hessians, 60. [25] Schroder, Hessian Occupation, 89. See Baer, Hessians, 59-60, for a discussion of German policies regarding civilians accompanying the troops to America, including physicians, nurses, cooks, clergy, laborers, servants, and maids. [26] See Christian M. McBurney, “Freedom for African Americans in British-Occupied Newport, 1776-1779, and the ‘Book of Negroes,’” Newport History, Vol. 87 (Summer-Fall 2017), 4, 6. [27] Baer, Hessians, 263. [28] Schroder, Hessian Occupation, 73-76. [29] Ibid., 74. [30] Hessians, x. See also Lowell, Hessians, 44. [31] Baer, Hessians, 5, 94. [32] Ibid., 104-105. [33] Ibid., 257. [34] Quoted in Schroder, Hessian Occupation, 65-67. [35] Stephan Popp, Popp’s Journal, 1777-1783, reprinted in the Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (April and July, 1902) and translated by Joseph G. Rosengarten. Also in The Hessians plus The Voyage of the First Hessian Army and Popp’s Journal (Pierceton, IN: Townsends, nd). [36] Quoted in Schroder, Hessian Occupation, 117. For Capt. Malsburg’s full and interesting description of Newport, see Schroder, Hessian Occupation, 67-70. [37] Baer, Hessians, x. [38] Ibid., 45. [39] Hessians, 216. [40] Baer, 5, 25-26. [41] Schroder, Hessian Occupation, 117-8. [42] Ibid., Hessian Occupation, 70; Baer, Hessians, 265. [43] Lowell, Hessians, 220. For a first-hand account of the entire occupation from a British military perspective, see Frederick MacKenzie, The Diary of Frederick MacKenzie, Giving a Daily Narrative of His Military Service as an Officer of the Regiment of Royal Welch Fusiliers During the Years 1775-1781 in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and New York, Vols. I & II (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1930). [44] Baer, Hessians, 264; Schroder, Hessian Occupation, 5. [45] Quoted in Schroder, Hessian Occupation, 5. [46] Popp, Journal, 10-11. [47] Ibid., 11. [48] Baer, Hessians, 269. [49] Schroder, Hessian Occupation, 6. [50] Popp, Journal, 11. See also Schroder, Hessian Occupation, 159. [51] Samuel G. Arnold, History of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, vol. I (New York, NY: D. Appleton & Company, 1860), 434. [52] Baer, Hessians, 264; Schroder, Hessian Occupation, 99. [53] Hessians, 41-42. [54] Baer, Hessians, 25-27; Schroder, Hessian Occupation, 71-72. [55] Baer, Hessians, 25-27; Schroder, Hessian Occupation, 71-72. [56]Popp, Journal, 9-10; Schroder, Hessian Occupation, 93, 126-27; Baer, Hessians, 266. [57] Christian M. McBurney, The Rhode Island Campaign: The First French and American Operation in the Revolutionary War (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2011), 51-52. McBurney’s book is the authoritative book on the May raids and the July-August American offensive campaign. [58] McBurney, Campaign, 52-62. [59] Quoted in McBurney, Campaign, 56. [60] McBurney, Campaign, 62. See also Schroder, Hessian Occupation, 112-15. On May 30, one hundred British troops of the 54th Regiment, commanded by Maj. Edmund Eyre, raided the small town of Fall River in Massachusetts to destroy three saw mills, which produced wood planks for flatboats. Hampered by several misfortunes, the raid succeeded in destroying only one of the saw mills. No German soldiers took part in this raid. McBurney, Campaign, 66-69. See also Schroder, Hessian Occupation, 115. [61] McBurney, Campaign, 76-77. See also Schroder, Hessian Occupation, 8, 125-127. [62] McBurney, Campaign, 50. [63] Ibid., 71. Within the next few weeks, the British scuttled ten of its warships and thirteen transport ships rather than having them seized by the French. Ibid., 95. [64] Ibid., 108-10; Schroder, Hessian Occupation, 135-36. [65] McBurney, Campaign, 112, 114-19; Schroder, Hessian Occupation, 139. [66] McBurney, Campaign, 126-27, 136, 138; Schroder, Hessian Occupation, 141; Baer, Hessians, 266. [67] McBurney, Campaign, 149. [68] Ibid., 168-69. [69] McBurney, Campaign, 176-79. For an overview of the battle see also, “The Battle of Rhode Island,” Rhode Island Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, Accessed August 15, 2022, at http://rhodeislandsar.org/battleri.htm, and Patrick Conley, The Battle of Rhode Island: A Victory for the Patriots, pamphlet (Providence, RI: Rhode Island Publications Society, 2005). [70] McBurney, Campaign, 177-79. [71] Ibid., 187-93; Schroder, Hessian Occupation, 143-51; Baer, Hessians, 267-68. For the Black Regiment, see: Robert A. Geake with Lorén Spears, From Slaves to Soldiers: The 1st Rhode Island Regiment in the American Revolution (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2016). [72] McBurney, Campaign, 203. [73] Ibid., 194-95. [74] Ibid., 193. [75] Ibid., 193. Patrick Conley, Rhode Island historian laureate, concludes differently in his The Battle of Rhode Island: A Victory for the Patriots, arguing that the battle was a “clear-cut American victory” and laments that it is “unrecognized by most historians.” Ibid., 21-23. [76] Schroder, Hessian Occupation, 161-167. [77] Ibid., 161-167. [78] Crytzer, Hessians, ix-x. [79] Ibid., 274; Baer, Hessians, 1.

Sources

Arnold, Samuel G. History of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. Vol. I. New York, NY: D. Appleton & Company, 1860.

Baer, Friederike. Hessians: German Soldiers in the American Revolutionary War. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022.

“The Battle of Rhode Island.” Rhode Island Society of the Sons of the American Revolution. Accessed August 15, 2022. http://rhodeislandsar.org/battleri.htm.

Conley, Patrick T. The Battle of Rhode Island: A Victory for the Patriots. Providence, RI: Rhode Island Publications Society, 2005.

Crane, Elaine Foreman. A Dependent People: Newport, Rhode Island in the Revolutionary Era. New York: Fordham University Press, 1985.

Crytzer, Brady J. Hessians: Mercenaries, Rebels, and the War for British North America. Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2015.

Geake, Robert A. with Lorén Spears. From Slaves to Soldiers: The 1st Rhode Island Regiment in the American Revolution. Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2016.

Johnson, Donald. “Occupied Newport: A Revolutionary City under British Rule”, Newport History, Vol. 84, Summer 2015.

Lowell, Edward J. The Hessians and the Other German Auxiliaries of Great Britain in the Revolutionary War. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1884. In The Hessians plus The Voyage of the First Hessian Army and Popp’s Journal, 39-396. Pierceton, IN: Townsends, nd.

MacKenzie, Frederick. The Diary of Frederick MacKenzie, Giving a Daily Narrative of His Military Service as an Officer of the Regiment of Royal Welch Fusiliers During the Years 1775-1781 in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and New York. Vol I & II. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1930.

McBurney, Christian M. The Rhode Island Campaign: The First French and American Operation in the Revolutionary War. Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2011.

McBurney, Christian M. “Freedom for African Americans in British-Occupied Newport, 1776-1779, and the ‘Book of Negroes,’” Newport History, Vol. 87 (Summer-Fall 2017), 4.

Popp, Stephan. Popp’s Journal, 1777-1783, Reprinted from the Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, April and July, 1902. Translated by Joseph G. Rosengarten. In The Hessians plus The Voyage of the First Hessian Army and Popp’s Journal. Pierceton, IN: Townsends, nd.

Schroder, Walter K. The Hessian Occupation of Newport and Rhode Island, 1776-1779. Westminster, MD: Heritage Books, 2009.

Stensrud, Rockwell. Newport, A Lively Experiment, 1939-1969. London: D Giles Limited, 2015.